A Lifetime of Song: On Rita Dove’s “Playlist for the Apocalypse”

Teow Lim Goh considers “Playlist for the Apocalypse” by Rita Dove.

By Teow Lim GohNovember 9, 2021

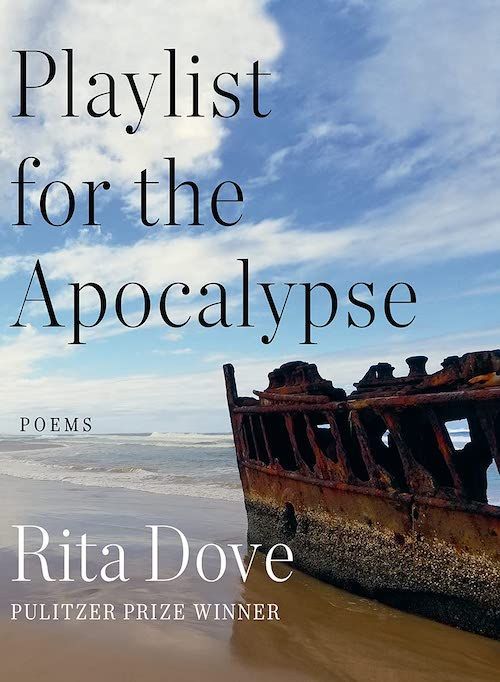

Playlist for the Apocalypse by Rita Dove. W. W. Norton & Company. 128 pages.

APOCALYPSE IS ON our minds these days. We are in the middle of a global pandemic that, as of writing, has killed nearly five million and sickened over 240 million people worldwide. The use of the word “apocalypse” to mean the imminent destruction of the world, however, is a modern one, first recorded in the late 19th century. It is rooted in the Greek apokalyptein, to “uncover, disclose, reveal.” The last book of the New Testament describes prophetic visions of the end of the world — and it is known as the Book of Revelation, as much a document of John’s struggles with the dark nights of his soul as it is a vision of apocalypse. Another way of saying this is: Perhaps apocalypse is not so much about the destruction itself, but rather the shifts, disclosures, and revelations of the soul when our usual defenses are stripped away by catastrophe.

Rita Dove’s new poetry collection, Playlist for the Apocalypse, draws from the past and present, from the segregation of Jews in Venice’s Ghetto to the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama; from her relationship with her mother to her struggles with multiple sclerosis to quiet and private moments in which the speaker’s world shifts, whether suddenly or imperceptibly. These poems, in the range of histories and personalities that they invoke, resemble a playlist, a curated selection of songs from a variety of albums and artists, tracking different voices, moods, and themes. They are less about the end times than the cycles of tragedy and redemption that humans seem wired to repeat.

Playlist for the Apocalypse is Dove’s first new book in 12 years and a capstone to a 40-year career in which she earned many of the highest accolades in poetry, including the US Poet Laureate, the Pulitzer Prize, and the National Medal of Arts. In a recent interview with Guernica, Dove says of this silence, “I was so busy being out there and speaking for poetry. I couldn’t hear myself anymore. And every time I would try to get the time and the quiet, there was never enough time.” In addition, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and could not write by hand anymore; she had to retrain herself to write on a keyboard and with dictation software. The pandemic shutdowns gave her space to hear her own voice, during which she gathered poems she wrote over three decades to see how they fit together.

Dove is known for writing about history from an intimate perspective. One of her best-known poems is “Parsley,” collected in her second book, Museum (1983). In 1937, Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered his army to slaughter anyone who could not pronounce the word “parsley” in Spanish, perejil, on the basis that the French-speaking Haitians could not roll their tongues for the “r” sound. In this poem, Dove begins with a villanelle in the voice of a Haitian worker in a sugar cane field, the terror of the dictator saturating this pastoral-like landscape, and pivots to a close third-person portrayal of the general in his palace, raging at his mother’s untimely death:

My mother, my love in death.

The general remembers the tiny green springs

men of his village wore in their capes

to honor the birth of a son. He will

order many, this time, to be killed

for a single, beautiful word.

Imagining the twists of the general’s inner life is not without risks, but in Dove’s hands, the poem is uncompromising and compelling. As Brenda Shaughnessy puts it, “Dove is a master at transforming a public or historic element — re-envisioning a spectacle and unearthing the heartfelt, wildly original private thoughts such historic moments always contain.”

Dove continues to work this tension between the private and public in Playlist for the Apocalypse. In her Poet Laureate lectures at the Library of Congress in 1994, she says of the need for poets to step out into the world: “Perhaps only then can we find the right mix between the interior moment and the pulse of the world. Perhaps when we begin to involve ourselves in the world. […] Only then will we hear the resonance inside ourselves.” Dove heard the resonances in the poems that make up her latest book during the apocalypse of 2020, but, besides a reference or two, these poems are not about the pandemic and its discontents. In the range of her stories, voices, and political engagement, she suggests that apocalypse is less of a sudden occurrence than an ongoing state of affairs.

The centerpiece of Dove’s new book is a song cycle titled “A Standing Witness,” written for a collaboration with composer Richard Danielpour that was supposed to premiere at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 2020. In these 14 poems, Dove bears witness to the last half-century or so of American history, from the Democratic National Convention of 1968 through Woodstock, Watergate, the Vietnam War, Roe v. Wade, the Iran hostage crisis, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the September 11 attacks, Barack Obama, and the rise of Donald Trump, among others. The titles of these poems, such as “Beside the Golden Door,” “Mother of Exiles,” and “Woman, Aflame” are phrases from Emma Lazarus’s sonnet “The New Colossus,” inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty. The speaker does not reveal herself until the final poem, but it is not hard to guess from the outset that she is Lady Liberty.

Dove sets the tone and tack of the sequence in the first poem, “Beside the Golden Door,” in which the speaker establishes herself as a witness and says:

[…] No matter

what ragged carnival may be thronging the streets,

what bleak homestead or plantation of sorrows

howling its dominion, Truth would say these are

arrogant times. Believers slaughter their doubters

while the greedy oil their lips with excuses

and the righteous turn merciless; the merciful, mad.

Here Dove deftly encapsulates the malaise and tumult of the last few decades that led up to the present moment. The activist movements of the 1960s and ’70s began conversations about traditional and hierarchical structures of power that are still relevant today. At the same time, reactionaries felt threatened by these critiques of their power, seeing peaceful protests as violent incursions. At the heart of these ideological clashes is the question of truth and credibility, of whose story the culture validates — the question that undergirds this sweep of American history.

One of the most fascinating pieces in this sequence is the second poem and first testimony “Your tired, your poor…” set in 1968:

Who comforts you now that the wheel has broken?

No more princes for the poor. Loss whittling you thin.

Grief is the constant now, hope the last word spoken.

The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy that spring and summer marked a turn in America’s social temper; the seemingly wide-eyed innocence of the postwar boom turned sinister. Dove marks this moment with an elegy that begins as a villanelle. In the repeating lines, she asks where we find solace when the social order as we know it has ruptured — that is, how we cope when we are faced with apocalyptic change. But she cuts the form short, the final stanza reduced to a single line of “[g]rief is the constant now. Hope: the last word spoken,” the broken wheel unable to keep turning.

But the broken wheel rumbles on through wars near and far, each time catastrophic depending on one’s point of view, be it Nixon’s lies that the nation accepted as inevitable or the agency and autonomy that women gained with legal and safe abortion. On Muhammed Ali, she remarks, “No black man / strutting his minstrel ambitions // deserves those eloquent lips.” For those who believe that black people should be a permanent underclass, Ali’s very existence feels calamitous. There are moments of cautious hope, such as the election of Barack Obama, but the series culminates in “Keep Your Storied Pomp,” a sonnet on the delusions, lies, and violence of the Trump administration:

Welcome to the Age of Babble!

Here a twitter, there a tweet; a tiki torch march

back to the Good Ole Times of mayhem and murder.

But the poem is not just a catalog of the unimaginable; in the couplet, she turns to the believers, the greedy, and the merciless:

Oh indolent friends, bitter patriots:

What have you triggered that can’t be undone?

Dove takes apart and writes into Lazarus’s sonnet, both thematically and formally. Though “A Standing Witness” is not strictly a crown, in its cycles and echoes Dove uncovers the shifts and disclosures of the American psyche that fuel these apocalyptic times.

In the abovementioned Guernica interview, Dove says, regarding her penchant for persona poems, that she first does research until she knows as much as she can about the subject:

It sounds kind of mystical, but when I do start to write, I feel like they’re almost writing through me, or that we’re in conversation with one another, because every persona poem is actually an autobiographical poem, too. Though I don’t like to write about myself per se, I should amend that and say I don’t like to write an unfiltered self.

There are plenty of persona poems in Playlist for the Apocalypse, from Henry Martin, a freed slave from Monticello who worked for years as a bellringer at the University of Virginia, where Dove has taught for three decades, to Sarra Copia Sullam, a poet and arts patron in 17th-century Jewish Venice. But she also pushes beyond her tendency toward historical characters to write a section of poems in the voice of a spring cricket.

Dove attributes the idea of the spring cricket to her daughter Aviva at the age of five. These are not frivolous poems; the spring cricket ruminates on subjects such as Negritude, Valentine’s Day, and hip-hop. In writing from this unusual perspective, she brings humor and surprise to what could have been shopworn topics, such as in “The Spring Cricket’s Discourse on Critics”:

I’m gonna sit here

awhile, & watch the dew

drop: its letting go

so lurid a metaphor for Failure,

I can’t help but take it

out of circulation. Everybody’s

hungry, everybody’s hunkered

in their hedges, hanging on —

in the end nothing’s left

to talk about but Style.

But the spring cricket is not merely a comic persona. In the final poem of this section, “Postlude,” she has the cricket say, “You prefer me invisible […] // Out of sight, I’m merely an annoyance.” The cricket represents what is overlooked in our culture:

As usual, you’re not listening: Time stops

only if you stop long enough to hear it

passing. This is my business:

I’ve got ten weeks left to croon through.

What you hear is a lifetime of song.

By giving voice to the cricket, she is also reminding us that small does not mean insignificant, and that those seemingly on the sidelines often have something valuable to say.

In the final section titled “Little Book of Woe,” Dove rips off the masks and speaks from an unfiltered self about her struggles with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. She remarks in the notes that with an experimental treatment, she has been able to adjust to a relatively normal life, but for years she hid her condition from the public and even her parents. These poems look inward, meditating on the shifts in her world as she faces what must have felt like her private apocalypse. She writes about making soup as comfort food when she got her diagnosis, about living with chronic pain, about learning to dance again:

If you think about it,

everything’s inside something else;

everything’s an envelope

inside a package in a case —

and pain knows a way into every crevice.

These are also poems in which she contends with her mortality, such as in “Last Words”:

I won’t meet death in a field

like a dot punctuating a page

it’s too vast yet too tiny

everyone will say it’s a bit cinematic

Dove steps back into her life and unearths resonances within herself, private moments, transforming the quiet cataclysms behind her public success into a lifetime of song.

¤

LARB Contributor

Teow Lim Goh is the author of two poetry collections, Islanders (Conundrum Press, 2016) and Faraway Places (Diode Editions, 2021), and an essay collection Western Journeys (2022). Her essays, poetry, and criticism have been featured in Tin House, Catapult, Los Angeles Review of Books, PBS NewsHour, and The New Yorker.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Two Roads: A Review-in-Dialogue of Tracy K. Smith’s “Such Color: New and Selected Poems” and Arthur Sze’s “The Glass Constellation: New and Collected Poems”

Victoria Chang and Dean Rader consider “Such Color” by Tracy K. Smith and “The Glass Constellation” by Arthur Sze.

Two Roads: A Review-in-Dialogue of Douglas Kearney’s “Sho”

Victoria Chang and Dean Rader consider “Sho” by Douglas Kearney.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!