As the Strands Come Together, Patterns Arise: A Conversation with Carolyn Kuebler

Ladette Randolph interviews Carolyn Kuebler about the relationship between writing and editing and her debut novel, “Liquid, Fragile, Perishable.”

By Ladette RandolphMay 13, 2024

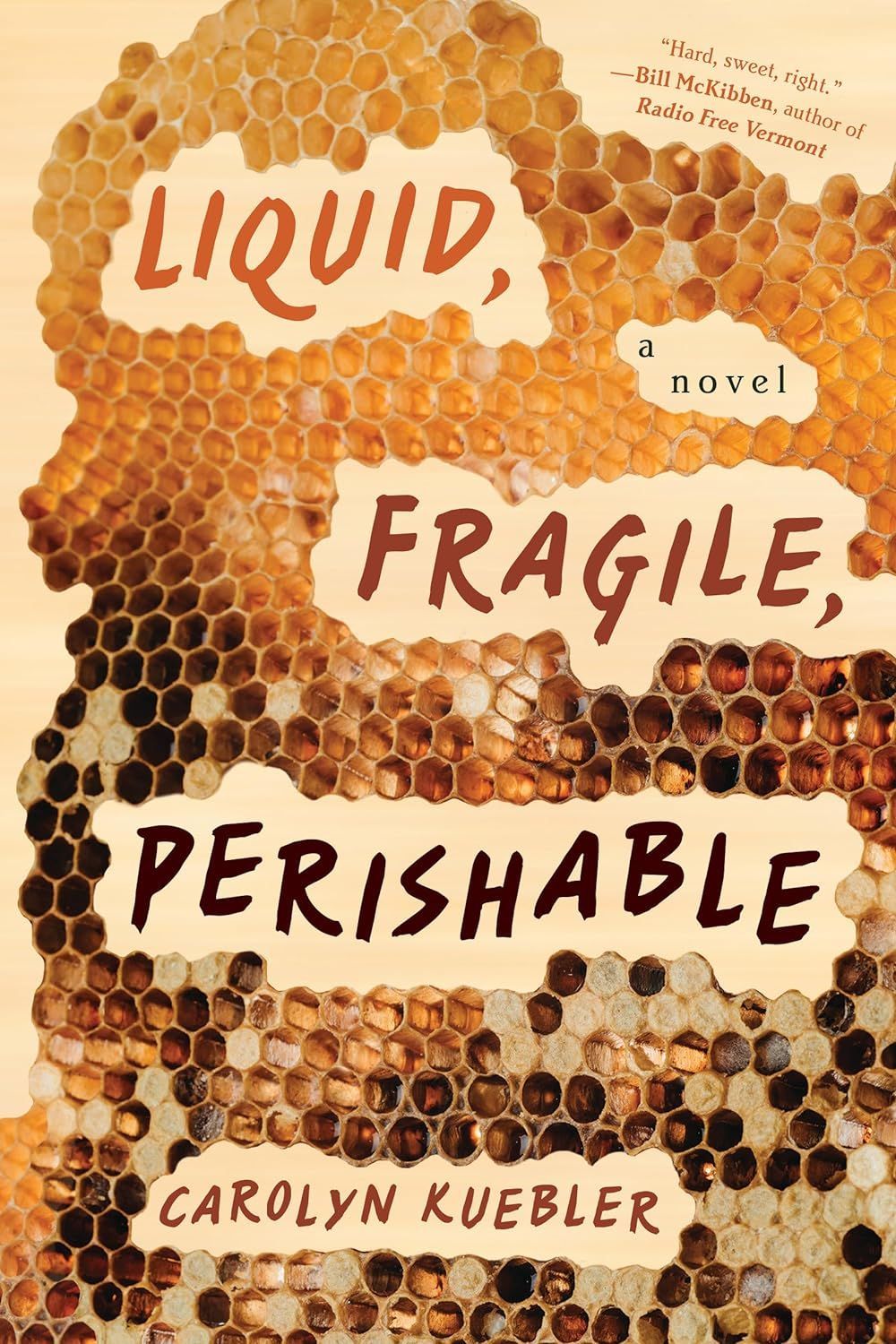

Liquid, Fragile, Perishable by Carolyn Kuebler. Melville House. 352 pages.

CAROLYN KUEBLER, longtime distinguished editor of the New England Review, is publishing her debut novel, Liquid, Fragile, Perishable, in May with Melville House. The novel, which examines the effects of a traumatic event on the members of a small community in Vermont over the course of a year, also serves to chronicle the effects of climate change—large and small—in that same community. Our wide-ranging conversation about the novel and our dual roles as literary journal editors and novelists took place over a period of several days in April 2024.

¤

LADETTE RANDOLPH: Was there a particular event or situation that inspired this novel?

CAROLYN KUEBLER: Several years ago, a Middlebury College student went out during a snowstorm, and for months nobody could find him. Not until spring, after the ice melt, did his body turn up in the river, the one that runs through the middle of town and that I cross every day while walking to work [at the NER office]. During those months, it felt like the whole town was haunted, by him and by his mother, and by the possibility that any one of us might find him. Everyone seemed involved in some way, even those of us who didn’t know him and had no part in the search. I’d only lived here a few years back then, but it was the first time I felt this thread running through us all, felt it being tugged, and how we all sort of shifted together.

Maybe part of why this incident struck me so intensely was that it brought me back to when I was 14 and my cousin, who was only 17 herself, drowned in a freak boating accident. It was so sudden and felt so personal. Terrible things happen all the time, and I knew that people endured much more. But this event broke something in me, some confidence in the order of things. I became preoccupied by imagining the pain of others, people who were even closer to her—how could they live with it? How could any of us live with it? Why were we allowed to? And yet we did. We had to.

There were other inciting motivations and obsessions—for one, the sudden onset of colony collapse disorder, when bees first started dying in huge numbers, and the mind-boggling effects that the loss of something as small as a honeybee could bring, and seeing just how complex and vulnerable these natural systems are. Also, the hurricanes and intense rainstorms that have begun to happen on a regular basis all around Vermont, and the lack of snow. How fast things are changing.

The format of your novel is unusual. The very short paragraphs, usually only one or two sentences, forced me to slow down and read more like one would read the stanzas of a poem. What led you to make this stylistic decision?

I knew what I wanted this novel to be about, and who the people were, long before I figured out how to write it. I tried writing it backwards in time, then with a single first-person POV, then as a “once upon a time long ago” omniscient kind of thing, then in large elliptical paragraphs, and so forth. It just kept getting bigger and bigger, and I got lost in the details. It wasn’t until I slowed down to writing one sentence, then taking a breath, then writing one more, over and over, that something clicked. It started to finally sound how I wanted it to sound, to feel like the right container for the rhythm and the interiority that I was after. The first scene I wrote that way turned out to be the first scene of the novel, and it was when I came to the mallards shaking out their wings, and Leonard casting out his line in the sun, that I thought yes, this is how it can be done. I was terrified that it would only work for me, with the rhythm of my own mind, and was so relieved when I showed the first few sections to a writer friend and she got it, and said yes, keep going.

I had to write most of the scenes first in a free burst, in big blocks of text. Then I’d pull out what I needed, one line at a time, and kind of sculpt it out of that big block of clay. I wrote each of the scenes many times—I believe there are 101 of them in the end—but some of them were with me from the start: the girls at Circle Current, Jeanne watching the staties drive by with their flashing lights, Nell waking up to fresh snow.

I also kind of see it as laying out strips of color, or weaving, and as the strands come together, patterns arise, and when the colors blend, when an image repeats, you feel something happen the way you feel something happen in a painting or tapestry. There’s also narrative energy driving this book, but it’s important to me that those lines do their own work.

I appreciate this description of your writing and revising process. The first part of your process, the bursts of writing, attempting many approaches to structure or points of view, and so on, feels familiar to me, but I especially like your metaphor of weaving different strips of color (so appropriate, given your character Sarah’s expertise as a weaver), observing the patterns that arise and the ways images repeat to guide the writer in finding the deeper story and how it should be told. It’s a wonderful illustration of the deeply mysterious, organic work of revision. It sounds like you discovered how to write this book as you were writing it. Is that true? Based on what you’ve learned, do you have any advice for those writers who are thinking about writing a novel?

Given how long it took for me to find my way, I’m probably not a good giver of advice, except to say, be patient with yourself. Novel writing is such a personal and idiosyncratic thing, and there’s rarely a good reason to do it apart from fulfilling some serious internal nagging. I wish I could have discovered how to write this based on my reading, going off the model of so many books I love, but it really did take a lot of starting over, learning as I went along. And then, once I had the general shape of the thing, revising was a very intricate process. But also a real joy.

Part of my difficulty was that, while I admire all kinds of writing, the stuff I click with most deeply and personally usually does something unexpected with form that can’t be replicated. Maybe because it knocks me off-kilter in a way that makes me more receptive, somewhere in my unconscious. I’ll never forget the sense of recognition and deep thrill I got from reading The Waves (1931) by Virginia Woolf, and that’s a really bad example to follow if you’re a young writer trying to find your way. For some writers, the more traditional rules of craft suit them just fine—and some really great work comes out of that craft. But Freytag’s pyramid or the apex-denouement narrative arc doesn’t always contain what you’re trying to do, just like not every poem wants to be a sonnet, even though these are incredibly rich and varied forms.

I’d also say, don’t be afraid to share work in progress with someone you trust, and don’t hold out for perfection—either in the writing or in the response. Let some light in on the process.

The choice to tell this story polyphonically created a lot of layers of complexity for me and helped to emphasize the major themes of the book. As you mentioned above, this choice came much later in the writing process. How did you choose which writers’ voices to prioritize in this way?

Including different points of view was central to the whole conceit, once I figured it out, even though I knew [doing so] could make it tricky for people when they’re just orienting themselves to the novel. You have to be okay with not knowing for a while, which is something I’ve gotten used to from reading a lot of poetry, to accept some disorientation and not worry so much about the exact connections. That said, it’s very carefully plotted and time-lined. I have a map, outlines, sketches, a spreadsheet even—a lot of scaffolding. I did try to keep it as clear as possible without disrupting the spell of interiority I was trying to cast.

Of course, I have no idea what goes on in anyone’s head but my own, and sometimes not even that. But I can’t help imagining, and I think that being in the imaginative space of fiction gives us readers and writers a chance to think more expansively and possibly behave more generously toward each other. To me, fiction—reading it and writing it—has always been a way to take the chaotic, violent, frightening, and beautiful experiences that come just from being alive and give them a little more order than they might otherwise have, and to make them shareable across all kinds of differences, to make them last beyond a single moment in time.

To be immersed in a story, to be among made-up people and to ride the momentum of narrative, is also just fun. The multiple points of view in my fiction are essential for creating a sense of the organism, in which each part is important even as one might contradict another. Nobody is right or wrong, exactly, in their way of seeing each other, the town, and the things that happen there. They’ve each been dealt a different set of expectations and possibilities, which influences how they perceive anything from the weather to the meaning of hard work.

I like what you say about how fiction is a “chance to think more expansively and possibly behave more generously toward each other,” a shared and sustained act of empathy. I’m interested in the structure of the book, starting in spring with Nell and ending the following spring with Nell. Nell is such an intriguing character, but it took me until near the end to fully appreciate the ways her story anchored the book. Could you talk about how you see her role in the novel?

You’re right, Nell is something of an anchor, not just for the book but also for me as a writer. She is more philosophical and removed, or she tries to be, but the physical world and the social world keep pulling her back. She’s also more attentive to the weather because she has the time and because she walks everywhere. I had a very clear sense of her psyche and emotional register, but it was harder for me to pin down how she got there, so finally I just had to write her whole backstory to keep it from shifting around too much, even though none of that would appear in the [novel] itself. It’s funny for me to realize that I started writing this character when I was several years younger than she is, but by now I’ve caught up. The same thing with the teenage girls. When I first imagined them, my daughter was in elementary school, but now she is in college and has grown older than them.

The structure—one year, from May to May—contributes to the sense of repetition, that fluidity you mentioned, and how things constantly change and yet stay the same. Even when terrible things happen, spring still comes back. It offends us sometimes to see the renewal that happens when we are not in the mood, when it doesn’t reflect our perception of what should be. How dare the daffodils come back? Sometimes that doesn’t seem right. But their reappearance often ends up changing things for people internally too; it’s hard to avoid being affected by a blue sky and the smell of mud thawing, especially when you live in a northern climate. I wanted that to be part of the story too—like Jeanne, I’m interested in people. But it’s never just about people; they’re not independent from all the other workings of the world.

And May in Vermont is just irresistible. It always takes me by surprise, when I can get on my bike and feel the warm wind on my skin and not have to put on all those layers. Lately, these warm days have shown up at weird random times in February or March, and you can still get a brutal frost in April, but May marks a pretty reliable end to the muddy shoulder season. And there’s so much light!

I live not all that far from Vermont, in Western Massachusetts, so I share your experience of how reluctantly spring comes, how much we long for it and yet are somehow surprised by May. The landscape of the Green Mountains in Vermont is as much a character in this book as the human characters. The reader’s immersion in the beauty, fragility, and potential for destruction of this environment emphasizes one of the major themes of the novel, the variety in the human response to climate change. You mentioned briefly above that colony collapse in bees and erratic weather inspired aspects of this novel. Would you mind elaborating on that aspect of the story? How central was that concern for you as you were writing?

Thank you, yes, that sense of fragility and potential destruction is another thing that haunts this book, that haunts me and anyone who loves it here. To imagine Vermont without the paper birch and sugar maple, without the migrating geese and mergansers, is just more than I can bear, and yet I know this change is coming.

Since the late 19th century, Vermont’s department of tourism has done a great job positioning the state as a place to go for pastoral beauty and outdoor recreation, a place apart from mainstream industrial-consumer culture and the frenetic pace of things. And for decades, people have come here looking for that, and so the vision has been fulfilled somewhat, by people looking for an alternative way to live—or just to go on vacation. I remember coming to Vermont as a kid, to go camping, and marveling over the lack of billboards and roadside litter. It really felt different. But it’s also a place of deep poverty and resentment, like the rest of the United States. There’s the visible ideal—big red barns, grazing Holsteins, old white churches and meeting houses—and these are real. But there are also the complicated and long-lasting effects of human intervention—the logging that initially stripped the land and pushed out native populations, and then the talc mining, the ski industry, the stone quarrying, all of which have left their scars on the land and the people. It’s not quite so “green” as we’ve been led to believe.

I think this is changing, but the variety of human responses to climate change have for a long time been divided along the lines of economic status. The oil companies did a pretty good job passing the buck to the individual with the whole “carbon footprint” thing, which puts the responsibility on the individual consumer when [companies] knew that the power to make real change was theirs. When it was seen as a question of individual choice, people who could invest in solar panels and insulate their homes, or who had time and capacity for composting and bicycling to work, would get a bit self-righteous and judgmental of people who had shitty gas-guzzler cars and were too exhausted by low-paying jobs to plan healthy organic meals, plant kitchen gardens. It became yet another way for people to divide up into ideological camps, with their outward signs of allegiance and petty differences. And it was a great distraction from the oil and gas industry’s own responsibility to make a significant change in their business model.

This novel takes place about 15 years ago, when we thought burning corn oil instead of fossil fuels might save us. When you could expect at least a few days of temperatures in the negative double digits every winter. The natural world that all Vermonters live near, or on the edge of, seems to get more and more tame with the milder winters, cell phone coverage reaching deep into the forests, access to the internet expanding. But the woods and rivers are still wild, and humans can still be outwitted and undone by their power. That’s not going to change.

I want to ask a question relating to the other role both of us play in the world of letters as editors of influential literary journals. Could you talk a bit about the ways a life of reading and editing informs and nourishes—even possibly saps—one’s own creative energies?

The ideal day job for a writer depends so much on temperament and opportunity and luck, and editing and publishing, where reading is a built-in part of the work, is one possible way—one that works for me, though it took a while. I have a writer friend who works dull, repetitive jobs in the medical industry for as few hours as possible a week to get by, and there’s a long-standing romanticization of the writer who works in obscurity as, say, a taxi driver, while producing great works of art. But it seems there are fewer and fewer jobs that pay enough for a person to work them part-time and get by, much less have time for writing. Most jobs sap our creative energies, and the margins are getting slimmer. The most visible model for aspiring writers is the writing teacher or professor job—which seems ideal because a teaching schedule comes with built-in breaks, publication is expected and supported, and sometimes they even get a research assistant and money to travel. But there are downsides to that too—like the precariousness of adjuncting, which is where most writing teachers find themselves.

One challenge to writing while working as an editor—which I imagine you’ve experienced too—is seeing just how much is being produced compared to what’s being published and read. Some of it’s even quite good. And for me, editing sharpened my internal critic, which was already a loud voice in my head, one I would let loose onto my own work long before it was ready.

But being exposed to so many different voices, so many different approaches to writing, such persistence, can also give me the motivation and energy to keep at it. And I love the way editing gives me a chance to spend time inside another writer’s head, to tune into the different ways to work a sentence, a rhythm, a structure. It keeps me agile and inspired.

I want to turn our attention back to the book again. I was intrigued that as the novel ends, many of the characters are on the cusp of major change. The question of how things might unfold for them stayed with me long after I’d closed the book. I appreciated how skillfully (and subtly) you created ambiguity for the reader, bringing us into the creative process as we continue to imagine possible futures. The randomness and fluidity of life seemed to me to be one of the major concerns of this book.

I like how you put that: how imagining what happens next is like being invited into the creative process. That’s what all reading is, isn’t it, especially of fiction and poetry—a creative act on the part of the reader. And I love to imagine these characters moving on and doing things in your imagination, as they certainly are in my own. In fact, they’ve stayed with me to the point that I’ve seen them through the next 13 years after we leave off, through COVID-19 and the Trump administration, through the warmest winters on record, to the mounting threats to our local bees, to a time when the babies are teenagers and the teenagers adults and the world has changed yet again. By now, I think we’ve moved on from “liquid, fragile, perishable” to “potentially hazardous.”

As for randomness and fluidity, I think those are both apt descriptors of the way things play out on a large scale; they give shape to this novel but are also more broadly applicable to the movement of life on earth. There’s only so much our choices and our hard work will determine what our lives will be like, which contributes to that sense of the randomness, and there’s fluidity in the way the planet keeps making its rotations with or without our being ready for it. We put a lot of emphasis on making good choices, especially for young people, and certainly we do have some important decisions to make in how we live, but what ultimately happens is going to be determined at least as much by things we can’t control—tiny things like genes and chance encounters between people, but also huge things like the movements of the jet stream and the rising, warming oceans, which will make our world even less predictable, our conditions less livable. Does that mean we should give up making informed and thoughtful choices, that it’s all just random? No way. But I think it’s important also to acknowledge that there’s only so much your choices will change things, and to be able to live with that too. And you never know when a small decision will become a very big one, both for yourself and for your community and beyond.

¤

Carolyn Kuebler was a co-founder of the literary journal Rain Taxi and has been an associate editor at Publishers Weekly and Library Journal. For the past 10 years, she has been the editor of the award-winning New England Review.

LARB Contributor

Ladette Randolph is editor-in-chief of Ploughshares and co-owner of the manuscript consulting firm Randolph Lundine. A publishing professional for over 30 years, she was managing editor of Prairie Schooner early in her career and later an acquiring editor at University of Nebraska Press. In addition, she is the author of five award-winning books, most recently the novel Private Way (2022).

LARB Staff Recommendations

“D Is for Despair” Didn’t Sound So Good: A Conversation Between Bill McKibben and Elizabeth Kolbert

For Earth Day, Bill McKibben speaks with Elizabeth Kolbert about climate change and her new book “H Is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z.”

In Celebration of Ploughshares: Ladette Randolph Interviews Lauren Groff

"Ploughshares" Editor-in-Chief Ladette Randolph interviews Lauren Groff about her time as guest editor for the revered publication.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!