Did Philip Roth Read Judy Blume?

Sarah Arkebauer ponders the eerie similarities between Judy Blume’s 1977 novel “Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself” and Philip Roth’s 1979 novel “The Ghost Writer.”

By Sarah ArkebauerApril 4, 2023

WHEN JUDY BLUME reintroduced her novel Wifey, first published in 1978, in a 2004 preface, she related an anecdote about the reception of her often salacious fiction. “My mother, who went to high school with Philip Roth’s mother, met Mrs. Roth on the street,” she wrote. “Mrs. Roth had some advice for her. ‘When they ask how she knows all those things, you say, I don’t know, but not from me!’” This anecdote, a recollection illustrating these celebrated authors’ enmeshment in their bemused families, echoes themes in the work of both and raises questions about the extent of their proximity. Blume and Roth were born and raised just a few years and a couple of towns apart in Jewish households in northern New Jersey. As Blume’s anecdote makes clear, both have achieved a certain notoriety by pushing the bounds of appropriate subject matter, and both have been met with the sort of vehement criticism often levied at work deemed too risqué for popular consumption.

As it happens, Blume herself has gone on the record as being a fan of Roth’s fiction. She tweets with some regularity about her love of Roth’s books. Interviewed by The Irish Times about her 2015 novel In the Unlikely Event, which is based on the true, tragic story of a series of airplane crashes in the New Jersey town where she grew up, she said that she was “grateful” that Roth was already out of high school when the crashes happened, “or I’m sure he’d have written about them […] [a]nd he’d have done it so much better than I possibly could have because he’s a brilliant writer.”

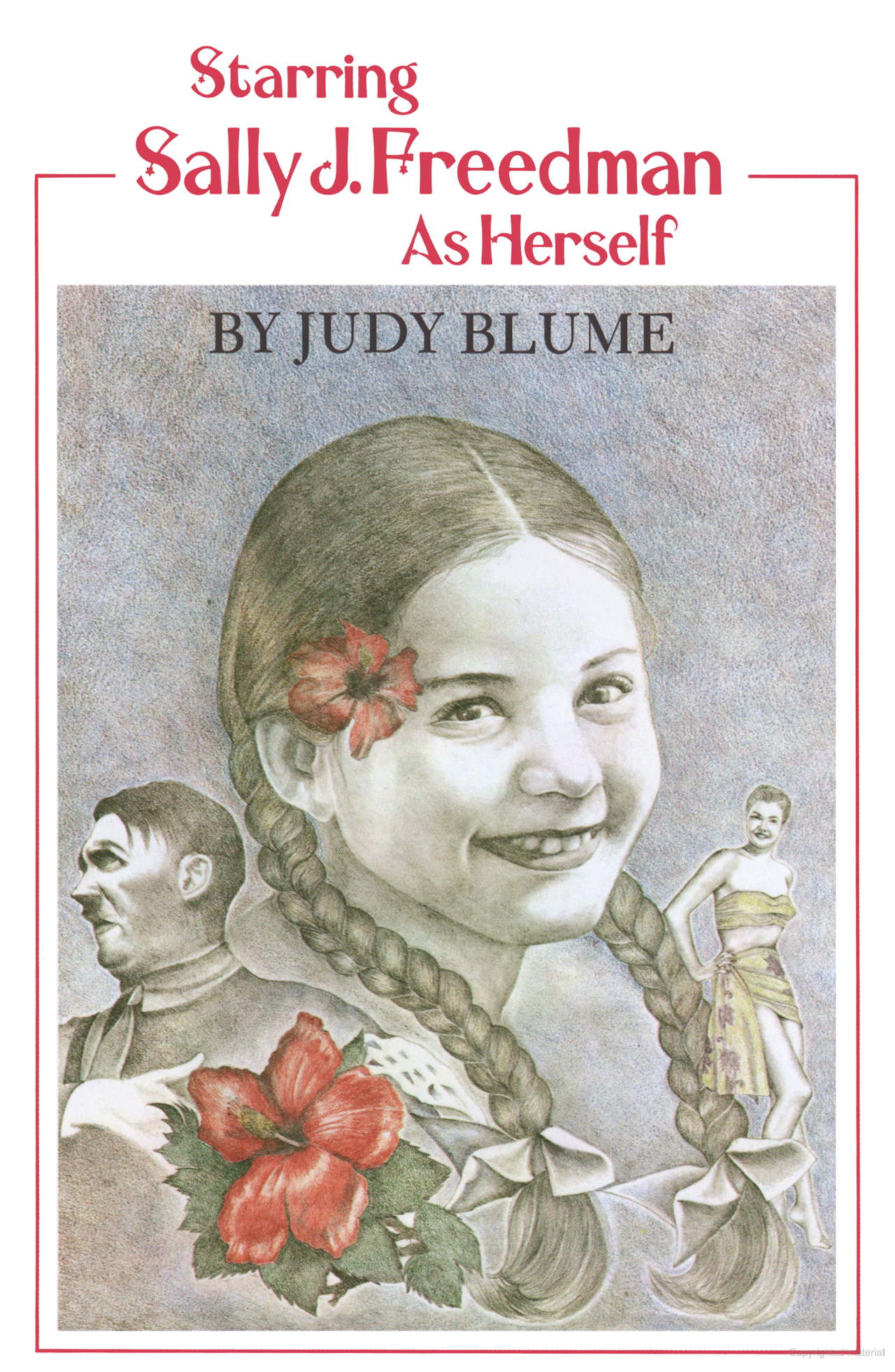

Both Wifey and In the Unlikely Event are novels for adults, and so Blume’s invocation of Roth feels less jarring in relation to those texts than it might with regard to her work for young adults. But there is also a striking similarity between Blume’s 1977 YA novel Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself and Roth’s 1979 novel The Ghost Writer. We know that Blume reads Roth, but did Roth read Blume as well? If Roth wasn’t a reader of Blume’s work, perhaps he ought to have been. When one reads Starring Sally and The Ghost Writer together, the parallels are clear: both are concerned with parents who are frequently perplexed or made uncomfortable by their headstrong children, whose exuberance and personal tastes are out of sync with how their parents think they ought to act. Both novels take up questions of a child’s place within the family, the transgressions of good taste possible through imagination and art, and the reverberations of the Holocaust and its effects on children.

There is also the matter of their plots. Each novel is set in the years following World War II, which its protagonist—a budding writer born in the 1930s, and semi-autobiographically based on each novel’s author—spent in suburban New Jersey. Now, this protagonist has arrived in a strange landscape, the familiar comforts of childhood far away—an environment that provides the backdrop for a domestic drama, as the story bursts obsessively into focus for the young writer. Hints appear that an important personage from the war is not in fact dead but living a robust post-Holocaust life in the United States. The protagonist becomes obsessed with the true identity of this person, building a narrative around the revelation of their secret identity, one that allows the protagonist to come to terms with the traumas of the war and the ruptures that the Holocaust and its aftermath have created within the protagonist’s family.

¤

In Blume’s novel, 10-year-old Sally J. Freedman leaves New Jersey in 1947 for Miami, where she, her mother, her grandmother, and her brother have all decamped for the winter to help her brother recover from a bout of nephritis. There, she becomes obsessed with the idea that Mr. Zavodsky, an elderly man living in her apartment complex, is actually Adolf Hitler in disguise. (That Mr. Zavodksy is seemingly Jewish—like Sally’s grandmother, he reads the Yiddish newspaper The Jewish Daily Forward religiously—doesn’t faze Sally, who sees this choice of reading material as a sick sort of camouflage.) The appearance of Hitler in Miami Beach is especially disturbing to young Sally as her grandmother’s sister and niece were murdered in the Holocaust, the reality and legacy of which she thinks about frequently and in gruesome detail. At one point, when her friend falls and skins her knee while biking, Sally becomes convinced that Mr. Zavodsky, who was sitting in the park nearby, will have turned her friend’s skin into a lampshade by the time she’s able to return with an adult to tend to the girl’s wounds.

But even as the specter of Hitler is horrifying to the child’s sensibilities, it is also intriguing: if Sally can heroically identify this monster and bring him to justice, she feels that she might get a sense of closure to the trauma he has wrought within her family. Moreover, if Hitler can be alive, then Tante Rose and Lila might be as well. Thus preoccupied, the narrative is peppered with interstitial daydreams in which Sally unmasks Mr. Zavodsky and makes him pay for his crimes, thus finding justice for her relatives and exerting some sort of control over the lingering tragedy of their murders. Indeed, death haunts the story, not only via Tante Rose and Lila but also in Sally’s father’s musings about his upcoming birthday, when he will be the same age at which his older brothers died. If Sally can bring Hitler to justice, it seems, that might serve as a bulwark against both past and future deaths.

In Roth’s novel, published two years later, 23-year-old Nathan Zuckerman has gone up to snowy New England to stay with the acclaimed writer E. I. Lonoff. While there, he becomes convinced that Lonoff’s former student, Amy Bellette, who visits to work with the old man’s personal papers, is actually Anne Frank in disguise. Zuckerman decides that the young Amy is having an affair with Lonoff that centers on her revealing her true identity to him. If Zuckerman can prove her identity, he imagines, then he, like Blume’s Sally, can heal a rift in his family, getting back into the good graces of his father, who disapproves of a story he has written on the basis that it appears to fuel the fires of antisemitism. The famous girl—imagined now as a young adult around Zuckerman’s own age—offers him an opportunity to work through the loss of childhood innocence and familial confidence he now faces.

Zuckerman, who is smitten with Amy himself and desperate to follow in Lonoff’s literary footsteps, pictures the young woman solving all his problems by returning to New Jersey on his arm. He envisions the protection a marriage to the unveiled Anne Frank could offer him: “Oh, marry me, Anne Frank, exonerate me before my outraged elders of this idiotic indictment! Heedless of Jewish feeling? Indifferent to Jewish survival? Brutish about their wellbeing? Who dares to accuse of such unthinking crimes the husband of Anne Frank!” The redemption offered by bringing a murdered child back to life includes, for Zuckerman, a restored esteem in the eyes of his family and community elders, esteem he has only recently lost as he grows older and moves further away from their cultural insularity.

While both Blume and Roth have frequently faced critics’ ire for the purported lewdness of their work, these two novels are far from being the most explicit entries in each author’s respective corpus. Nevertheless, a strange prurience emerges in both novels in how they intertwine the righting of some historical wrong with the pleasures of romance. In The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman spins out an entire narrative in which Amy confesses her true identity to Lonoff in the context of the sexual relationship he imagines between the two. In Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself, Sally’s scheming against the perfidious Mr. Zavodsky is interrupted by a quest to find a “Latin Lover” in Miami (a role for which she casts her classmate Peter Hornstein) for her first kiss. And Blume’s novel displays a certain prurience in matters of taste: young Sally sees bright red lipstick framing an open-mouthed smile as the height of chic and is impressed by the glittering diamonds and slinky evening clothes of the “companion” of one of her father’s business acquaintances. Sally’s mother worries over the tile choice for their family’s bathroom renovation, arguing that a certain combination makes the room look like a “bordello,” a word Sally doesn’t understand, though she delights in the aesthetic.

This occasional tawdriness underlines what might seem the inherent inappropriateness of the novel’s core subject matter. After all, shouldn’t Hitler’s depredations be too terrible a topic for a young girl to think—much less fantasize—about? Sally’s friends and family seem to think so. When she suggests to friends in New Jersey that they play a game of pretend featuring a daring rescue from a concentration camp, or when she picks Hitler in a game of 20 questions, her friends are mortified. Mentioning to her family the possibility of Hitler living among them in Miami Beach, her grandmother can only respond, “God forbid.” But Sally cannot put him out of her mind the way a child might be expected to: the Holocaust remains front and center in her imaginative play because of how the event shaped her family.

One might think back to these moments when reading the list of questions about Zuckerman’s short story that are included in a letter from a local judge to whom Zuckerman’s father has pled his case regarding the story’s inappropriateness: “What set of aesthetic values makes you think that the cheap is more valid than the noble and the slimy is more truthful than the sublime?” That a tawdry sexual fantasy (Zuckerman’s being far more explicit than Sally’s) should be juxtaposed with the apparent manifestation of Holocaust ghosts is an aesthetic curiosity that marks both texts.

¤

One could perhaps point to Isaac Bashevis Singer’s 1968 New Yorker story “The Cafeteria” as a possible progenitor for both novels. In this story, the writer-protagonist is not the person who indulges the Holocaust-related fantasy; instead, he offers a recollection of his acquaintanceship with a young refugee woman he met at the eponymous cafeteria. Partway through, she confesses to Singer’s narrator a story she insists to be absolutely true; late one night, she claims, just before the cafeteria burned down, she walked in to see Hitler conducting a meeting with a gaggle of henchmen. Singer’s protagonist doesn’t believe her; as he muses afterward, “How can the brain produce such nightmares?” It is only later that, unsure whether he has recently seen the woman again from afar, he thinks she might have been telling the truth: “If time and space are nothing more than forms of perception, as Kant argues, and quality, quantity, causality are only categories of thinking, why shouldn’t Hitler confer with his Nazis in a cafeteria on Broadway?”

If both Blume and, later, Roth drew on Singer’s story for inspiration, it is notable that they decided to update the ghost-of-the-war sighting from an event reported by another to a conviction held by the protagonist. As its metaphysical musings suggest, Singer’s story retains an air of unreality, but Blume and Roth both play the fantasy straight, spinning it out from a single sighting into an extended narrative. The reader will recognize the fiction involved in their supposed identifications. When Zuckerman confronts Amy about her physical similarity to Anne Frank, she shuts him down, and he meets this denial with mournful reflections not on the historical person herself but on the persona created through the pages of her diary: “I could not lift her out of her sacred book and make her a character in this life.” This wistful tone, remarking on the mysterious endurance of the diary itself, refuses to give the personal fantasy full emotional closure. Meanwhile, when Sally sees Mr. Zavodsky’s corpse wheeled out of their building following a fatal heart attack, her fantasies of revenge come to an end, but not her desire for it. She is left to mourn another death without the option of payback.

Anne Frank might seem like a better focal point for a girl like Sally than for a young man like Zuckerman, and vice versa regarding Hitler. Indeed, the narrative setups feel strangely backward. But to place Anne Frank in Sally’s world would have been an historical anachronism. Though both books were written in the late 1970s, the slight difference in their respective chronological settings is crucial: Roth’s story takes place in the early 1950s, when Anne Frank’s diary had not only taken the publishing world by storm but had also been the basis of a popular (soon to be Tony-winning) recent Broadway production; in Blume’s late 1940s Miami, by contrast, nobody has yet heard the tale.

On its own merits, however, Anne Frank’s story is an interesting one to consider with respect to how the Holocaust has been depicted for and by child narrators. Though this was not well known until after the publication of Blume and Roth’s novels, Otto Frank bowdlerized his daughter’s diary, editing out material he felt to be sexually inappropriate as well as more painful moments of familial discord, before the text’s publication in 1947 (the English translation appeared in 1952). In this way, Otto Frank himself also created a fantasy of his daughter. For all that adults might want to protect children from the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust, the fact remains that these were events that happened to them as well, as both Anne Frank’s diary and Judy Blume’s novel attest.

And so, in a funny way, does Roth’s. Faced with the failure of his fantasy, Zuckerman pivots to seek professional validation through his recognition of the literary merits of the diary. In an echo of the elder Lonoff’s identification of literary promise in the writings of young Zuckerman, Zuckerman himself is eager to put his stamp of approval on The Diary of a Young Girl’s child author. As he explains its merits to Amy following his plea for the two girls to be one and the same: “She was a marvelous young writer. She was something for thirteen. It’s like watching an accelerated film of a fetus sprouting a face, watching her mastering things.” And later: “[S]he’s like some impassioned little sister of Kafka’s. […] It could be the epigraph for her book. ‘Someone must have falsely traduced Anne F., because one morning without having done anything wrong, she was placed under arrest.’” Here, Zuckerman puts Anne Frank’s juvenilia on the same plane as a classic of modernist literature, propping up his own literary star by way of a classic of young-adult literature—and thus reminding us, as Blume’s work does too, that children’s experiences are not separable from adult events.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sarah Arkebauer holds a PhD in English and comparative literature from Columbia University. She is at work on a book about historical fiction and millennial girlhood. She lives in St. Louis.

LARB Staff Recommendations

On Lives and Counterlives

Two solid biographies of the late Philip Roth, one authorized, one not.

Daring Holocaust Education: On Yishai Sarid’s “The Memory Monster” and Jean-Claude Grumberg’s “The Most Precious of Cargoes”

Miranda Cooper reviews Yishai Sarid’s “The Memory Monster” and Jean-Claude Grumberg’s “The Most Precious of Cargoes.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!