Are You Living Your Best Multiverse Life?: An Interview with Jonathan Carroll

Evan Selinger talks with Jonathan Carroll about how to choose your best multiverse life in his new novel “Mr. Breakfast.”

By Evan SelingerJanuary 14, 2023

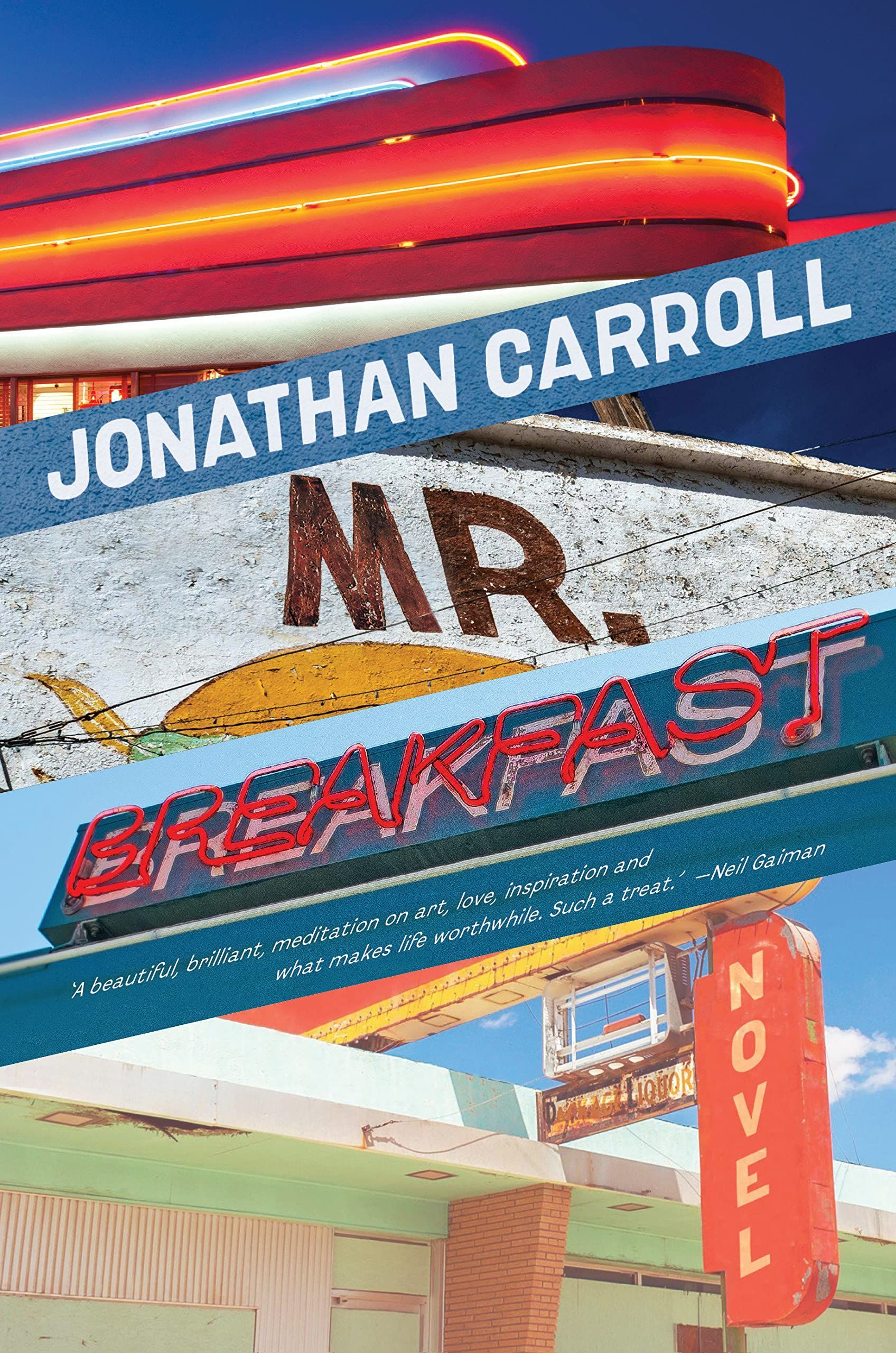

Mr. Breakfast by Jonathan Carroll. Melville House. 272 pages.

OVER THE COURSE of 20 novels, Jonathan Carroll has become internationally renowned for establishing a singular vision and style — a highly imaginative, genre-crossing, and wonder-fueled approach to crafting memorable characters and building extraordinary worlds. Carroll’s prose, which has earned a Pushcart Prize, two French Fantasy Awards, a Bram Stoker Award, and a World Fantasy Award, doesn’t just stick with you long after you put down his books. It imprints deep into your psyche, amplifying the beauty and absurdity of everyday life while highlighting the metaphysical in the seemingly mundane.

We met virtually to discuss the rich literary and philosophical dimensions of his most recent book, Mr. Breakfast — a highly accessible yet deeply existential and delightfully strange meditation on how to live your best multiverse life.

¤

EVAN SELINGER: Friedrich Nietzsche proposed a test that he called “eternal return.” The idea is to embrace your fate without resentment and say yes if offered the chance to repeat forever every joy and pain you’ve experienced. Did Nietzsche influence your exploration in Mr. Breakfast of how different people would react if given the opportunity to use a magical tattoo? The tattoo enables them to explore, as spectators, alternate timelines where their lives take different turns. It also lets them choose a new life if they so desire.

I ask because your novel leans into the existential drama of the scenario. Some of your characters, like Graham Patterson, the protagonist, accept the proposal. Others, however, follow Nietzsche’s suggested path and forgo the tattoo’s power.

JONATHAN CARROLL: I think, at one point or another, most people wonder, “What would my life have been like if I’d jigged instead of jagged?” Even the successful people I know have been tickled by that question. The simple answer to it is, if you like your life as it is, why look elsewhere to improve or change it? Obviously, Patterson is tempted by the possibility at the beginning of the novel because his life at that point is a mess. On the other hand, the tattoo artist Anna Mae and Anthea both like their lives, despite major setbacks, so they aren’t tempted. I know someone in their seventies who said they knew their life was good after realizing they had no bucket list. There was nothing they still wanted to do to “complete” themselves or their life. I think that’s what most of us should aim for.

Your novels are often classified as magical realism, and Mr. Breakfast has several magical elements, including the tattoo. Is it fair to interpret the tattoo as a literary device for exploring the real conversations most people have with themselves about how life may have gone if they only made different decisions about important things, like selecting a job and romantic partner and committing to whether to have kids? In these instances, we tell ourselves stories, and the stories are works of fiction because there’s no way to know what could have been.

You’ve got it spot on.

Is that why you don’t reveal why the tattoo has magical powers and instead maintain a sense of mystery about it throughout the novel?

I have always said that the worst part of a horror film is when you see the monster for the first time. Because until that moment, everyone in the audience has conjured their version of a scary monster. But when we see the actual Creature from the Black Lagoon or Freddy Krueger, we’re almost inevitably disappointed. Because nothing could be as scary to me as the monster I imagined. The same is true with why the tattoo has magical powers. If I leave it up to the reader’s imagination, rather than saying, “Once upon a time in a Japanese Buddhist temple, a monk discovered …” then they can create and embellish their own delicious reason why the tattoo holds its power.

If you could harness the power of the magic tattoo, would you check out the lives of other Jonathan Carrolls?

Back in the 1990s, I left Vienna for almost two years to go to Los Angeles and write screenplays. It was the only other life I had ever been tempted to live. I realized at the time that it was now or never. After two years there, I knew I preferred life in Vienna, so I returned. That was my version of trying on another life.

Was it hard to try out another version of yourself? As one of the characters in Mr. Breakfast declares, “Most people would rather die than make big changes in their lives.” And how did you determine that the original Jonathan Carroll is preferable?

After riding through the big Northridge earthquake back then, I realized that I was a novelist who’d only been writing scripts for two years but no novels. To me, novels were always more important, but they’d been on hiatus in my head for 700+ days. That realization struck hard and was a big deciding factor to return to Vienna. Symbolically, I arrived in Los Angeles with one suitcase and one dog. When I left, I had one suitcase and the same dog. So no, it wasn’t hard to make the transition in either direction.

Is choosing to use the tattoo an ethical decision?

I think that depends on whether there are other people in your life, like a spouse or children, who would be affected. If it’s just you and leaving one life for another will do no damage (as such) to others, then you get a green light.

Are other considerations relevant? For example, imagine that you’ve enjoyed many years of prosperity in your present life from egotistical behavior. But the tattoo offers an alternate life where your work provides tremendous value for countless others but feels less rewarding or leaves you less well-off financially.

Most people I know who are caught up in their own lives and (selfish) needs don’t seem to be the type to give it all up suddenly to devote the rest of their lives (or change lives) to working for the good of others. The comedian Bill Burr has a funny routine where he says we like to imagine that, if we lived back in the time of the Civil War, we would want to be part of the Underground Railroad and help people escape slavery. But the truth is, if we lived back then, knowing ourselves, we would most likely live exactly as we live now. Midlife crises don’t often lead people to reinvent their ways for profound life changes.

So, in the end, is there a right answer to the question of whether someone should use the tattoo?

I don’t think so.

If someone uses the tattoo to explore their other timelines, do any ethical considerations apply? For example, your story raises the question of whether there’s an obligation to prevent suffering. In this unusual setting, the only way for Patterson to help is to intervene. And doing so means he pays an unusual price: committing to live another version of his life.

I had trouble deciding how to end the novel. What would move Patterson to choose one life over the other? As is so often true in our everyday lives, the decision came not from some deep thought process but rather spontaneously. To paraphrase the boxer Mike Tyson, you think you’ve got everything figured out until you get punched in the face. The interesting question to me is, what is a better decider for big questions in life — when we’ve spent a good deal of time thinking something through, or spontaneously as the moment calls for an immediate decision?

Can you elaborate?

In my novel The Ghost in Love, I posit that we are not just one being, but many, like [I’m] a sort of United Nations of Carroll with different parts of me constantly bickering and competing with each other: 12-year-old me being dismissed by 30-year-old me because a 12-year-old’s opinions and views on life are immature and unrealistic. He should not be allowed to make big decisions because he’s just a kid, and what do they know? But 50-year-old me pipes up that 30-year-old JC is immature in his own way and should leave those important matters to the older versions because they’ve seen more and have more insight. Add to this the quick decisions of the 27-year-old versus the slow decisions of the 60-year-old — which are more valid and trustworthy.

How does this view that we all contain multiple, incongruous selves relate to Patterson’s initial frustration that he can’t locate an authentic core of his being and channel it into his standup comedy? Can we ever be authentic?

He’s lost at the beginning of the story. He knows he’s not good enough to be a successful comedian. He knows he fucked up his relationship with his girlfriend. He knows his buddy, the doctor, was right in telling him he needed to change radically to be a success but was too chicken to do it, and on and on. When you know you’re a failure in life and have no idea of how to get out of that psychic black hole, it’s hard to figure out who the authentic you is. Even with success, a lot of people get lost in finding their “bee” or even recognizing it when they catch a glimpse.

The tattoo plot makes Mr. Breakfast a multiverse story and thus part of the zeitgeist. Why are multiverse stories so popular? They’re everywhere, from the inescapable Marvel Cinematic Universe to the critically acclaimed film Everything Everywhere All at Once.

My problem with the Marvel universe is that it’s so far removed from my mundane and everyday experience that, in a way, it has no connection to real life beyond the entertainment value of a kind of cartoon. Fun but forgettable. The multiverse universes I can relate to are the ones that mix the fantastic with the mundane so that I can be entertained by the bells and whistles and magic yet see something that relates directly to my own experience.

That’s a great way to distinguish your novel. But why is there such a hunger now for multiverse narratives? Are they providing comfort?

In the Depression, people flocked to Busby Berkeley’s ridiculously over-the-top films as an escape from the chaos and sadness of their lives. I think the same thing applies at least to some degree today as to why people flock to multiverse movies and novels. Life for many is at best stressed, and for too many, very close to the dangerous edge. To see larger-than-life heroes and villains fly around and fight dragons, etc., is a way to get out from under our grim cares for a few hours and breathe rarefied air. Like kids being read bedtime stories.

Like many multiverse stories, the role of chance is a powerful theme in Mr. Breakfast. Do you think most people underestimate the role that chance plays in their lives?

Absolutely. We so want life to make sense, to be logical. But then a freak storm blows through town and knocks a tree over on your brand new car. Why me? Why did I have to park there? Why a hundred other questions. The answer, of course, is chance, as mysterious and uncomfortable as that may be. In my novel Sleeping in Flame, a shaman says that we say we want life to make sense, but if it did, we would have gotten a lot more speeding tickets by now. What we really want is for life to make sense when we want it to make sense. Big difference. Chance doesn’t play favorites, although, for some unlucky people, they might understandably think it doesn’t like them.

The film Before Sunrise revolves around two people in their early twenties, Jesse and Céline, who develop a powerful romantic connection after a chance encounter. They spend a few intense hours together in Vienna, the city you’ve been living in for nearly four decades. It ends with the couple parting without exchanging phone numbers or addresses, promising to meet again at the train station in six months.

The viewer is left to ponder deep questions. Should they keep their promise and see where life takes them? Or is it better for Jesse and Céline never to see each other again and live in the memory of a perfect meeting that was too brief for the eventuality of disappointment to intrude?

A version of the conundrum plays a prominent role in Mr. Breakfast when characters ponder what you call the ice cream question. Should you eat a bowl of the perfect ice cream if you can only have it once in your life and no other scoop will ever taste as good?

You trace this question to the story of Dr. Faust getting 12 years of “unimaginable power and wealth” in exchange for selling his soul to the devil. But were you also influenced by Before Sunrise?

I know of a real-life Before Sunrise story. A student of mine had a long relationship with his girlfriend all through high school. They lived in different countries and swore at graduation to meet up in front of St. Stephen’s church in the center of Vienna in five or 10 years. The day came, and the man, still single, waited with great anticipation for his love to appear at the agreed time. She did, pushing a baby carriage. Turns out she was in an unhappy marriage and was deeply touched that her old love had shown up for their rendezvous, but there was no way she would leave her husband. However, if it were up to me, I’d always take the chance of meeting again, particularly if I had never tasted better ice cream than the kind they gave me once upon a time.

How much of your own life experience permeates Mr. Breakfast? For example, one of the characters gets excited to drink Bunnahabhain whiskey. There’s also a passing reference to a bullet journal, which I believe your son invented.

Yes, my son Ryder invented Bullet Journal, and that whiskey is the favorite of a friend of mine. I like dropping little Easter eggs in my books for family and friends so they can chuckle or grumble when they bump into them. How much of my own life is like Patterson’s? Very little. I taught college and high school for 20 years until I had a few books under my belt and a wide enough readership to sustain me out of the classroom. Unlike Patterson, I live in Europe and cannot imagine what it would be like to stand onstage and tell jokes — much less aspire to do that for a living. Many years ago, I had dinner with a famous comedian who liked my books and asked to meet. At one point, they said they liked the humor in my work a lot and suggested I try writing for them. Curious, I asked how much they paid. They said an astronomical sum per minute. Gulping, I managed to say, “That’s a hell of a lot of money for one minute’s work.” Instead of answering, they held up a finger and looked at their watch. A very long time passed in silence. I didn’t understand what was happening. The silence continued until, finally, they held up the finger again and said, “That was one minute. Try writing enough material for a two-hour show.”

Should we take the ice cream story literally? Is there a perfect version of the treat that experts would agree isn’t just great but can’t be beat? And how does it apply to more complicated things like love?

Of course it’s subjective. But I can give you numerous examples of small perfect versions in my life that I am satisfied with and feel no need to look further. In other words, I found the perfect ice cream and don’t need to taste others because this is it. When I was in high school, my girlfriend at the time wore a beautiful dress to senior prom. I remember asking her how she knew that was the one because she had apparently tried on many others before choosing that dress. She said something like, “I know there are probably other dresses I would like better if I saw them, but this one is perfect for me now, so I don’t feel the need to look any longer.” She had found a perfect ice cream, rather than the perfect ice cream, and it was enough. I think that’s both a good and eminently doable way of looking at things like that.

But when you decide something is good enough to be “small perfect,” how do you know you’re not settling? Isn’t that the existentially troubling thought that haunts so many people? Maybe you want to look at life with an attitude of gratitude like Anna Mae, who says, “I knew it was what I wanted to do with my life — nothin’ else.” But you’re human, and so you can’t stop the inner voice in your head from singing a tempting refrain about greener grass.

I disagree. If I like steak and go to a restaurant that serves a great one, I don’t think, while eating, “There must be a better steak than this one somewhere out there.” I’m content with what’s in my mouth. I never understand why very rich people spend so much time and effort trying to get more money. I know it’s a game for some, and for others an obsession, but that’s not a satisfying answer. In reality, how much is enough for a sane person? If something satisfies me, whether it be a steak or enough money in my bank account, I rarely think I want more or better. Those who are never satisfied with what they’ve got, even when it’s basically as good (or enough) as it gets, just strike me as being malcontents. They are rarely satisfied with anything.

Sure, some people have endless appetites and will never be satisfied because nothing could ever be enough for them. Others, like characters in many of your stories, end up being drawn to people and paths that are perfect pairings — in that small, perfect sense of taking context into account and choosing what, at the moment, is the right cheese that goes with the right wine. But isn’t there a third possibility? It’s the folks who are anxious that they don’t have enough experience to make a properly informed judgment.

Here’s an example. A good friend from my college days has exquisite taste — so much so that Roger realized my life would be much improved if I started reading your books. He was right. White Apples is one of my favorite books of all time!

When negronis became a popular pandemic drink, Roger said that they’re fantastic. And so, I tried one. Despite great expectations, I didn’t like it. The vermouth was too bitter. The experience sent me into an existential spiral. Instead of saying, “Okay, good news, that’s one cocktail to cross off my list,” my inner voice questioned whether this was a personal failure. Maybe I didn’t appreciate the drink because I lacked elevated taste. Perhaps I’m guilty of settling for less complicated beverages that are easier to enjoy. Maybe I could better mark future celebrations if I eventually started to enjoy more sophisticated drinks.

I’ll tell you a story that’s tangential to your example. Still, I think it’s a good solution to your question. A friend of mine is very religious. One day, I said to him, “What about the Nazis? What about children falling out of windows? How can you have faith when these things happen?” He’s a very quiet, calm person, and suddenly he turned to me, grabbed my shoulder very hard, and said, “Look, asshole, there’s a light. You know where it is. Try and walk in it.”

That’s it. That’s all you need to know. There’s always going to be better. There’s always going to be another alternative. But if you’re going towards something and reach it, it’s almost like the yellow brick road in Oz.

Is that part of what makes literature magical? When I finish your novels, I’m satisfied if a compelling character found the light. But I’m also leaving them in the middle of things. The story is over, and I don’t know if the light will continue to shine. Or if it will change what it illuminates.

We all want that satisfying, happy ending in books and life. But real life is sticky. When you break up with a lover, you want to shake hands and say, “Thank you for the time spent.” You don’t want to hit them in the head with a hammer, either physically or mentally. But that’s usually what happens.

Once you’ve found the light, hold on to it as long as possible. Eventually, it might go away.

¤

Evan Selinger (@evanselinger) is a professor of philosophy at Rochester Institute of Technology.

LARB Contributor

Evan Selinger (@evanselinger) is a professor of philosophy at Rochester Institute of Technology.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Hurray for Inventing New Genres or Whatever: On Dr. Moiya McTier’s “The Milky Way”

Joani Etskovitz explores the genres at play — from astronomy and mythology to self-help and romance — in Dr. Moiya McTier’s “The Milky Way: An...

The Fantasy Story as a Merciless Laboratory of History: On R. F. Kuang’s “Babel, or The Necessity of Violence”

Kurt Guldentops and Sungshin Kim trace the intellectual adventure that is R. F. Kuang’s “Babel, or The Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!