Are We Still Postmodern?: On Stuart Jeffries’s “Everything, All the Time, Everywhere”

Ed Simon reviews Stuart Jeffries’s “Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern.”

By Ed SimonMay 25, 2023

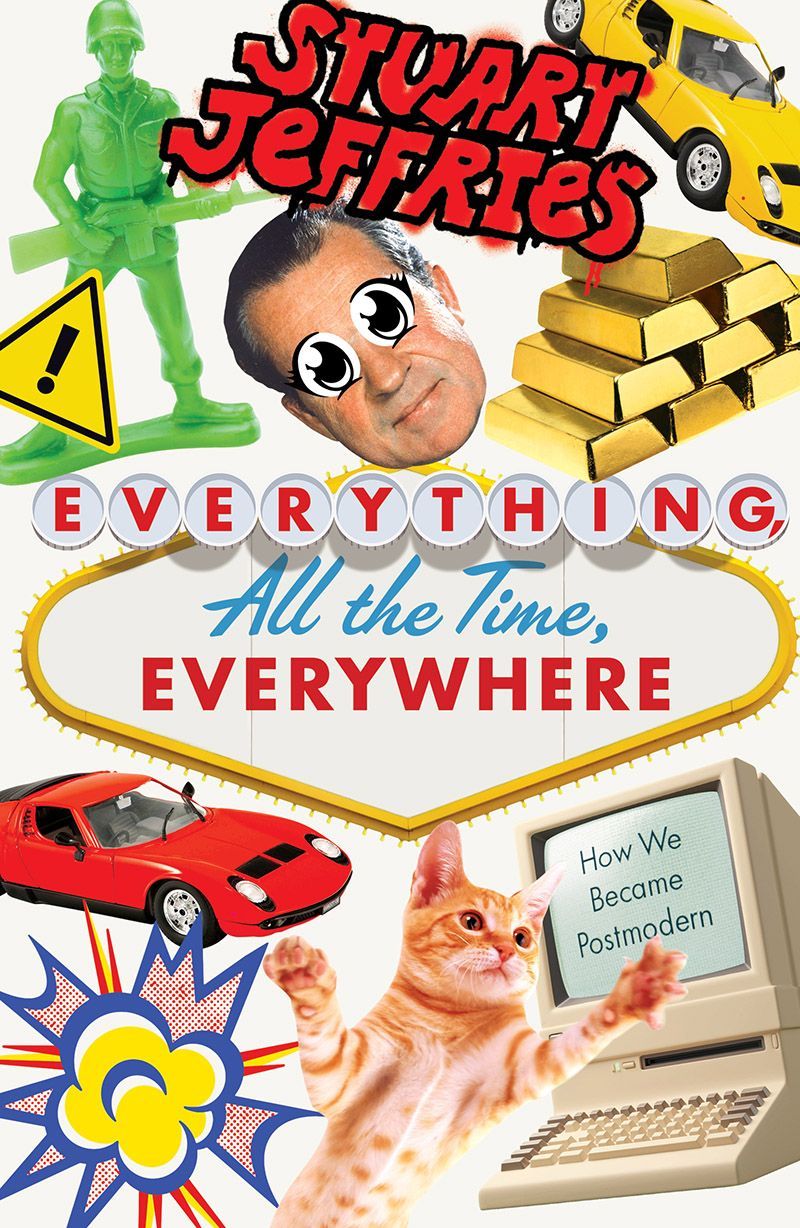

Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern by Stuart Jeffries. Verso. 384 pages.

AMONG THE TUDOR homes and neo-Gothic estates of Woodland Road, a private arboretum of a street hidden within the otherwise dense environs of Pittsburgh’s East End, there is a startling residence nestled beside the Gilded Age mansions. Finished in 1983, the Giovannitti House is a consummate example of modernist architecture. Composed of gleaming white concrete cubes and walls of sheer glass, the structure looks like a cluster of rectilinear clouds, a building of space and light despite the rigid rationality of its form. Form and function, parsimony and minimalism, a commitment to the complete integration of aesthetics and habitation, of life and art.

Ironically, that which would supplant modernism—predictably, the postmodern—had an address just a letter different, at the Abrams House right next door: a bricolage of a structure, composed of corrugated metal and massive windows, painted purple and green and with an undulating wave of a roof, appearing more like something you would find in Laurel Canyon than in Pittsburgh. The structure was designed by Robert Venturi, architecture’s most withering critic of Le Corbusier’s brutalist pretensions, who acknowledged being in favor of “messy vitality over obvious unity” in his 1966 manifesto Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. “I am for richness of meaning rather than clarity.” Punning on the iconoclastic commandment of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe that, when it came to architectural adornments, “[l]ess is more,” Venturi told his students that “[l]ess is a bore.”

From 118 Woodland Road to 118-A Woodland Road, there is a veritable monograph on the transitions from modernism to postmodernism, a hypothetical volume that would presumably rehash all the usual questions of whether the prefix in postmodern means “after,” “more of,” “against,” or somehow all three. The Giovannitti House exemplifies modernism’s commitment to Big Ideas: its totalizing, systematizing, clinical aspirations and its utopian desire to remake society. Reflected in its white walls are the specters of not just Mies and Le Corbusier, but also of Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, Arnold Schoenberg and Dmitri Shostakovich. Of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Theodor Adorno, and Max Horkheimer.

By contrast, the hybridized cacophony of the ultraviolet catastrophe next door is a study in postmodernism’s adamantly anti-utopian grandeur, of pastiche and irony and playfulness, as colorful as the Roy Lichtenstein mural that once adorned its inner wall. Within the house’s bright primary colors are traces of the presence of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, Don DeLillo and Thomas Pynchon, Madonna and David Bowie. Of Jacques Derrida—Jean Baudrillard—Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. To the postmodernist, their forefathers were doctrinaire, stultifying, and authoritarian; for the modernist, their inheritors were glib, relativist, and superficial. Despite the ready-made stereotypes, any all-encompassing value judgment of postmodernism, whether it be a movement, a period, a theory, a discipline, a methodology, or a perspective, is bound to be incommensurate with the subject. How is it possible to survey everything from Simulacra and Simulation to The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars?

This explains the shortcomings of the still-worthwhile Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern (2021) by Stuart Jeffries, a British journalist and frequent contributor to The Guardian. Jeffries’s previous book Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School (2016) is the most well-written popular introduction to critical theory ever penned, a riveting account of the lives of Adorno, Horkheimer, Walter Benjamin, and Herbert Marcuse. Everything, All the Time, Everywhere isn’t quite as cohesive because it covers a more slippery subject than the Frankfurt School, which at least actually had a faculty roster. Somewhat arbitrarily dating the genesis of postmodernism to Richard Nixon’s abandoning of the Gold Standard, each of Jeffries’s 10 chapters tends to divide into threes, with a reading of an artistic text, a political event, and a philosophical work. The result is a book that is as multitudinous and contradictory as its subject.

Under Jeffries’s equally omnivorous appetites and withering gaze, there are considerations of the discordance of Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols (1977) and Jean- François Lyotard’s melancholic The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979), the empty silver curves of Jeff Koons’s Rabbit (1986) and the coquettish mindfuckery of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” (1984), the anti-politics of Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972) and the sleek elegance of the iPod, the anarchistic Technicolor misanthropy of the Grand Theft Auto games and the relativism of Michel Foucault, the nihilistic screenplay to Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) and the sophistries of Baudrillard’s The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (1991).

Jeffries’s argument can be best understood as an addendum to Fredric Jameson’s contention in Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991) that postmodernism developed as a “substitute for the sixties and the compensation for their political failure,” that all of the deconstruction and dismantling binary oppositions was merely a masturbatory replacement for political agitation, signaling not just the demise of utopia, but the demise of even the idea of the possibility of utopia. Jeffries writes that if “we are today scarcely capable of conceiving politics as a communal activity, because we have become habituated to being consumers rather than citizens,” then it is postmodernism’s fault. According to him, if there was an anarchic playfulness with the initial generation of theorists, then capitalism did what it always does and vampirically drained such thought of any of its subversion, leaving behind only relativism and amoralism, so that now “[f]reedom, opportunity and choice were reconfigured in narrowly economic terms that precluded selflessness, community-spiritedness and kindness.”

Here Jeffries benefits from three additional decades that serve to corroborate and complicate Jameson’s argument, while also complicating that narrative, for if postmodernism once was understood as the culmination of history, a type of plastic Hegelian Disney World, then history has obviously very much started again in the sweltering days of the Anthropocene. As Alan Kirby snarked in 2006 in the magazine Philosophy Now, postmodernism is “about as contemporary as The Smiths, as hip as shoulder pads, as happening as Betamax video recorders.” Indeed, in humanities departments where French theory was once a full-frontal assault on the regime of tweedy traditionalists, herringbone has so long been replaced with distressed leather that the radicals are now clearly the conservatives. Following 9/11, a certain segment of the smug punditocracy claimed that the terrorist attacks signaled the death of cool postmodern irony and the kickstarting of history once again, and even if that particular date is overstated, it does seem as if the motor of Grand Ideas has turned over. Yet at the same time, the most dystopian elements of our techno-infotainment-social-media-metaverse don’t merely confirm the most cynical prophecies of postmodern philosophy; they far surpass them. And, as Jeffries argues, “postmodernism still offers the best way of explaining how neoliberalism functions today.” So, are we still postmodern?

Any history of postmodernism must contend with such polyphonic nature, its slippery indeterminacy. Furthermore, it’s fair to ask if a grouping of figures as disparate as Derrida, Sid Vicious, and Mark Zuckerberg has more to do with chronology than consistency. Regardless, there are certain aspects of culture produced from the early 1980s until the turn of the century, and in the long aftershock of that moment, that can be systematized (ironically), maybe chief of which is a broad dismissal of any kind of objective reality. Declarations that “we have alternative facts” might not share the cultured rhetoric of theorists a generation ago, but they’re not incongruent with the Austrian philosopher Paul Feyerabend’s gleeful conclusion in his 1987 Farewell to Reason that “[t]here is no coherent knowledge […] There is no comprehensive truth.” “Fake news!” is just hyperreality in an outer borough accent.

Jeffries convincingly argues that these various attributes we associate with postmodern culture and theory—a valorization of fragmentation, a distrust of hierarchization, an irreverent aesthetic—became dominant in the 1980s precisely because such characteristics were congruent with the economic logic of privatized, libertarian neoliberalism. “These post-modern French theorists were not so different from the neoliberals who would, before the decade was over, take power in the White House and 10 Downing Street,” Jeffries writes, even if his claim that the “eleven years of Thatcher’s Britain constituted a piece of post-modern outsider art” might strike some readers as more snark than critique.

Despite the differences that may have separated Ronald Reagan and Thatcher from a philosopher like Lyotard, they shared the criticism of “metanarratives.” Neoliberalism is a metanarrative too—so is postmodernism, even if it denies it—with the former’s mythos being that history culminates in the comfortable embrace of the Market, the only god that has supposedly never failed, with the technocratic priests of finance tinkering with the details for the rest of eternity. Everything, All the Time, Everywhere draws a connection from postmodernism’s belief in the vanquishing of absolutist metanarratives to political theorist Francis Fukuyama’s (perennially simplified) argument in The End of History and the Last Man (1992) that previous eras might have seen grand struggles between different faiths or ideologies, but from here on out life “will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems […] and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.”

Indicating some anxiety of influence, Jeffries notes that Fukuyama once studied under the notorious deconstructionist Paul de Man when the former was briefly a literature student at Yale, pivoting to political science after judging much of such thought as “bullshit.” The Yale school’s endlessly flexible thought and rejection of absolutes made its way over to the Hoover Institution as well. Such figures “no longer believed in progress or totalising stories about human goals. What remained was radical pluralism and the fragmentation of ideals.” If the New Man of modernism was Lenin upon the dais imploring the workers to revolution, then the postmodern figure was Steve Jobs in his black turtleneck cradling an iPod. Not workers, or citizens, now only consumers.

Whether there is a solid ground to reality is an issue of epistemology, but that the contemporary world is structured in such a way as if it seems that reality has no solid ground—that’s an issue of politics (and ethics). “While some have argued that post-modernism is a pre-digital phenomenon,” writes Jeffries, “many of the phenomena of post-modernism—especially the notions of simulacra, fakery, irrationality, scorn for truth and doubt about reality—have reached their apogees.” This is where Jeffries has the benefit of hindsight over Jameson, for the former is able to write his study in an era of omnipresent digital connection, corporate-mediated social media, and virtual reality’s increasing replacement of the actual thing. Materiality may still exist at the intangible level of subatomic particles, but it certainly seems that the Gnostics of Silicon Valley have merged base with superstructure, that the actual world has been abolished in favor of our shared fantasies and collective delusions. If an imagined poststructuralist’s claim in 1983 that truth was a chimera seemed histrionic, in 2023 it’s conventional wisdom. “Digital technology and social media have hardly made post-modernism obsolete,” writes Jeffries. “[R]ather, they have given it new life.” For anyone who has spent time fiddling with artificial intelligence programs like Chat GPT or the art-generation algorithm DALL-E, there is a frightening prophecy to Jeffries’s observation, and an intimation of where such technology might lead us. If Baudrillard’s jeremiads about television and Disney World seem quaint today, a decade hence we might look back on the era of digital surveillance capitalism and Russian Twitter bots as halcyon.

Extrapolating from our current moment, it is easy to envision a 2033 dominated by deepfakes and virtual reality, where videos of politicians are made to seamlessly say things they never said or where dead celebrities are resurrected to star in new movies, where images of regular people are inserted perfectly into revenge porn and it’s unclear whether you’re talking to a real person or not. A truly post-truth epoch. All of it is postmodernism par excellence: fragmentation, bricolage, and a jaundiced antinomianism disestablishing reality itself. A paradox here, for precisely at the moment when history has started again, it seems that stable ground has finally given away to pure illusion. Now it’s most correct to say that we are in the meta-postmodern.

Returning to Woodland Road, and in search of an allegory, it could be noted that in 2022, despite the efforts of historic preservationists, Pittsburgh City Council did not prevent the new owners of both the Giovannitti House and the Abrams House from demolishing the latter, the first postmodern residence in the city now a pile of rubble. Lest that be seen as postmodernism’s defeat, you can travel only a few miles away to the gentrifying neighborhoods of the city where the characteristic architecture of six-story-tall apartment buildings for the precariat now rise: colorful boxes of playful shapes that some wags have termed “Chipotle brutalism,” structures that evoke the now-gone Abrams House, except far cheaper.

As Jeffries notes, “Everything is up for grabs, for sale at the right price, because there is nothing outside the market.” Postmodernism never broached any memorials or relics anyhow, because we have been living in the simulacra for nearly half a century now.

¤

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine and a staff writer at The Millions.

LARB Contributor

Ed Simon is the editor of Belt Magazine, a staff writer for Lit Hub, and an emeritus staff writer at The Millions. He is a frequent contributor at several different sites including The Atlantic, The Paris Review Daily, Aeon, Jacobin, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Killing the Buddha, Salon, The Public Domain Review, Atlas Obscura, JSTOR Daily, and Newsweek. He is also the author of several books, including Devil’s Contract: The History of the Faustian Bargain, which will be released in July 2024. He holds a PhD in English from Lehigh University and an MA in literary and cultural studies from Carnegie Mellon University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Originality Is Unmusical: On Scott Miller’s Pop Music Criticism

Ivan Kreilkamp looks at the late Scott Miller's pop magnum opus.

Yacht, Rocks: On HBO’s “The White Lotus” and Picturesque Dread

Jorge Cotte reviews HBO’s “The White Lotus.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!