Originality Is Unmusical: On Scott Miller’s Pop Music Criticism

Ivan Kreilkamp looks at the late Scott Miller's pop magnum opus.

By Ivan KreilkampApril 5, 2023

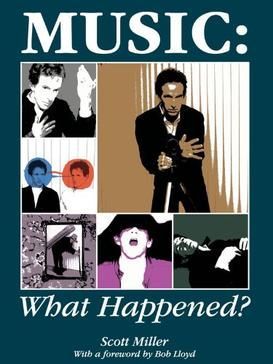

Music: What Happened? by Scott Miller. 125 Records. 270 pages.

IF YOU WERE a fan of what unfortunately was often called “college rock” in the 1980s and ’90s (Siri: make rock and roll sound like homework), you probably had at least a passing acquaintance with Scott Miller’s two bands, first Game Theory and then the Loud Family. Miller, tragically, took his own life in 2013 at the age of 53, leaving behind a respected body of musical work. The Game Theory catalog in particular was given a high-quality reintroduction by Omnivore Recordings over the past decade. But there’s one important aspect of his legacy that has been almost entirely overlooked: his rock criticism.

Miller’s jangly songcraft, in a post-Beatles vein, was ostentatiously wordy, literate, and syntactically dense. Critic and poet Stephanie Burt has observed that “[t]hroughout the Game Theory songbook […] you can hear an anguished concentration on language and its rules […] as if all those rules—once mastered—could help solve problems of love and sex, of friendship and estrangement.” If you think this sounds more like Wittgenstein than Black Sabbath, that’s not far wrong. Given the sheer density of literary skill, allusiveness, and craft on display in Miller’s lyrics, perhaps I should not have been as surprised as I was, a few years ago, to discover that he had also written an idiosyncratically brilliant work of rock criticism. But then, how many great songwriters have also produced accomplished music criticism—or even bothered to attempt to do so? (Yes, we see you, Bob Dylan, but 2022’s The Philosophy of Modern Song is a mixed bag.)

Miller’s book—bluntly titled Music: What Happened?—covers pop music from 1957 to 2011. It originated as a project on Miller’s blog, some of which is still available online. A friend recommended the book to me a few years ago, and I treasure my worn ex-library copy (rare used copies go for three figures). The suicide of an artist often bears down heavily on the interpretation of their work, which may have nothing at all to do with the anguish that led to the event. But even keeping that principle in mind, I find the experience of reading Miller’s critical summa to be at once intensely pleasurable and very sad. He clearly came to feel that the musical values his book champions had been abandoned. The book, the title of which refers to a downfall, reads as a slow-burn lament for a pop music culture—a set of musical practices and skills, and a certain kind of romantic dedication to music for its own sake—that Miller felt he had witnessed slowly dying away.

The book, which has a self-published feel, was first released in 2010 by 125 Records, a music label and publishing house that appears no longer to exist. It is organized in something like a Casey Kasem countdown mode: for each year from 1957 to (in a third edition) 2011, Miller writes brief essays (some only a few sentences long, none longer than a paragraph) about what he considers the best and most significant recorded songs of that calendar year. There are some additional rules: with a few exceptions—the Beatles, Elvis Costello in 1978—no artist is permitted to repeat in a given year’s chapter, which necessitates many hard choices. And, in a stipulation that will surely bewilder any younger reader today, each chapter’s musical selections were required to fit on a single CD (discs that Miller would burn for his daughters).

This all might sound like an unpromisingly fussy exercise in list-making, but it yields, as it turns out, a glorious wealth of epigrammatic insight, humor, and love of pop music—of its craft, its production, its wit and feeling, its democratic magic. If asked to name a single specific quality that most distinguishes Music: What Happened?, I would point to its consistent determination to connect the feelings and emotions produced by great pop music to the specific musical details that constitute it. For the 1960s and ’70s generation of rock critics (e.g., Robert Christgau, Greil Marcus, Ellen Willis) and their successors, excessive technical focus on music and recording craft arguably became something of a taboo, seen as evidence of a boringly literal-minded approach. When Willis elucidates the meanings of Dylan or Janis Joplin, or Marcus of Elvis Presley or Johnny Rotten, or Rob Sheffield of the Beatles or David Bowie, these critics are typically addressing mythmaking, self-construction, sex and the erotic, pop iconography, politics and ideology, subversion and resistance. They’re definitely not focused on chord progressions.

By contrast, Miller declares, simply, that “[t]here needs to be more music talk in music criticism.” Critics should possess “special gold-seeking ears” in order to be able to report on “how they unexpectedly turned into a love-struck adolescent over a vocal harmony or a piano run”; sometimes, he suggests, “the only words of value are whatever it was that happened on that A-minor in the second measure of the chorus.” It’s only this kind of focus on in-the-weeds technical stuff—“whatever it was that happened on that A-minor”—that can fully unlock and reveal pop music’s magic. In this sense, Miller can seem to approach pop music more in the mode of a jazz critic. He suggests that he aims to be a window into “the kind of talk bands themselves use”—the shoptalk of actual music-makers highly attentive to the details of their craft.

Miller’s gold-seeking ears locate musical details and nuances that few nonmusicians would notice: the “fascinating” drumming in Dale Hawkins’s “Susie-Q” (1957), “a swing basis but with lock-step eighth-note fills thrown in whenever the mood strikes”; the use, in the Posies’ “Licenses to Hide” (2010), of “a great vocal mike,” which is “often actually a result of how the mixing engineer made it sit”; “that recurring 3/4 instrumental break” in Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City” (1973), which “takes all possible crazy melodic turns but somehow still sounds as if it was intended from creation.” Seemingly technical observations often point to bigger ideas: the “third repetition of the great theme hook” in John Coltrane’s “Blue Train” (1958) sets up a listener “to be excited by the conventional” by “framing it with the unconventional.”

In an analysis of a Smashing Pumpkins song, of all things, Miller elucidates a broader credo: “Originality is unmusical. The urge to do music is an admiring emulation of music one loves; the urge toward originality happens under threat that the music that sounds good to you somehow isn’t good enough.” Miller values (and is even excited by) “the conventional,” by the genre-conforming. For him, “unoriginal” music that gives pleasure and sounds great is often preferable to innovative originality.

This working theory of pop music does not preclude the possibility of one-of-a-kind genius, although Miller’s geniuses are also generally hardworking craftspeople. About the Beatles’ “And Your Bird Can Sing” (1966), he comments that “if achievements like these spine-tingling harmony guitar cascades don’t issue from the clock-punching labor of a reigning musical genius, there is no wishing them into being with all one’s idealistic might.” I read this as a tacit confession from someone who perceived himself to be a talented nongenius, one who had spent a lot of time trying in vain to wish the equivalent of a Beatles song into being. But notice, too, that even this genius, John Lennon, must have put in clock-punching labor in order to produce the spine-tingling effect.

Music: What Happened? is quite often hilarious—I would tell you to try the entry on Big Country’s “In a Big Country” (1983), if you could find a copy of the book—but it is ultimately heartbreaking too. By the time he gets to the music of the 1980s, Miller has started making depressive asides that hint at a vision of a formerly rich 20th-century pop-musical culture that he felt was in the process of collapsing and diminishing. “I remember literally thinking: a lot more people’s hearts are in the right place these days—I shouldn’t worry that much about music being horrible,” he writes. On the Grand Funk Railroad (1974) and Kylie Minogue (1987) cover versions of Little Eva’s 1962 novelty hit “The Loco-Motion” (which Miller reveres), he warns not to “do what [he] did: watch these and the original on YouTube and weep for the decline of civilization.”

Miller’s later chapters become less fun to read: his tastes start to seem more backward-facing, and one senses his enthusiasm working harder to find worthy objects (he never fully got hip-hop or post-disco dance music). Miller also seemed to believe that what he viewed as a catastrophic cultural decline had also extinguished any chance that his own talents could take hold any longer in the culture at large. He observes, in a mini-essay on Kelis’s 2003 hit “Milkshake” (“an Asiatic synth-funk sex ritual song”—he likes it): “It was around 1983 that I felt ushered into the music business a bit, and around 2003 that I felt fairly completely ushered out.” Regarding the commercial failure of Miller’s bands, Kim Cooper observed that “[j]ust because you write the smartest pop lyrics of your generation, and have a master angler’s facility with hooks, and a few thousand people love what you do, that doesn’t mean anything. Scott learned that in the nineties.”

Like some of the musical obscurities he champions in it, Miller’s book is now out of print and virtually unavailable. My rare copy now feels a bit like a melancholy artifact of a lost world—a world that I, a Gen-X former 1980s college-radio DJ whose old vinyl albums now strike me as uncanny time capsules, emphatically shared with Miller. I miss it too. But if Music: What Happened? is a lament, and an act of mourning for a lost era of pop-musical creativity before Auto-Tune and Pro Tools, it is also very much a celebration and a work of enthusiasm. The book needs to be more widely available—that is, even a little bit available; could we get a reprint?—for the wealth of its insight and musical knowledge, for its intelligence, for its democratic vision of great music created by skilled craftspeople (including not just musicians but producers), and especially for the ways Miller helps us to trust our own ears, not to repudiate our own often-embarrassing first responses to silly or transient-seeming pop songs. He teaches us to believe that the music that sounds good to us is good enough: “[Y]our ears are always right, the embarrassment is always wrong.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Ivan Kreilkamp teaches in the Department of English at Indiana University. He has published three books, most recently Minor Creatures: Persons, Animals, and the Victorian Novel (Chicago UP, 2018) and A Visit From the Goon Squad Reread (Columbia UP, 2021). He has also published widely on contemporary fiction, film, animals, and pop music in Public Books, The New Yorker online, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The New Republic, The Point, The New York Times Magazine, The Village Voice, and elsewhere.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Patti Smith and Male Bias in Music Criticism

David Masciotra makes the case for a major critical reappraisal of Patti Smith.

Classic Rock’s Götterdämmerung

Ed Simon dances with Steven Hyden’s “Twilight of the Gods.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!