Apple’s Gimmick: On “Fingernails” and the TV+ Brand

Michael Szalay compares apples and Apples in parsing the streamer’s strategy financially, aesthetically, narratively, and otherwise.

By Michael SzalayFebruary 16, 2024

APPLES LITTER the Apple TV+ corpus. They appear in the title sequences of Mr. Corman (2021), The Essex Serpent (2022), and Silo (2023– ). Characters savor them meaningfully in Foundation (2021– ), The Changeling (2023– ), and numerous other programs. The fruit slyly associates the otherwise unrelated: in the postapocalyptic Silo, apples are placed in graves as nourishment for afterlives yet to come; in the Oscar-baited Killers of the Flower Moon (2023), they are placed atop graves, presumably for the same reason. On the face of it, these might seem little more than subtle winks to Apple diehards, easter eggs to remind even those who care to notice that this is just entertainment, after all. It’s fun to wonder what makes these Apple programs, but surely we miss the orchard for the trees if we think Cupertino cares overmuch about such low-hanging fruit.

Apples in The Changeling, Killers of the Flower Moon, and Silo (Apple TV+)

This way of reading Apple’s apples depends in part on the commonly held assumption that the laws of genre remain our best guide to film and TV. Studios and streamers might brand their content, but they do so weakly and unobtrusively so as not to impede the enjoyment of those possible millions who find themselves in the mood for this or that familiar narrative. Nobody sinks into the sofa at the end of a long day and asks themselves if they’re in the mood for Netflix or Apple. Or at least critics don’t think anybody does.

To be sure, many have been quick to note the generally affirmative, straight-down-the-middle tenor of Apple’s typically expensive, star-studded (and bland) programming. But few note more than that. And while many have noticed Apple’s obsessive product placements, few, if any, have asked what gravitational field those products exert on the actual “content” in which they are embedded. On the contrary, it has seemed straightforward enough why Cupertino litters its mise-en-scènes with its own devices—so much so that these devices appear no more meaningful than Apple’s apples.

In 2019, The Wall Street Journal found that Apple products were “visible in an average of 32 camera shots per episode.” In The Morning Show’s (2019– ) first season, for example, “an Apple logo is visible in roughly one-third of those shots.” Rival brands are scarce, and the iPhone receives the most airtime by far. The reason for these placements? The Journal quotes a marketing expert who estimates their value at “tens of millions of dollars” per episode. “How brilliant is it for Apple to go into the content business?” asks a second expert. “Wouldn’t we rather watch a show with product than watch the commercials?”

iPhone product placement in WeCrashed (Apple TV+)

Based on TV+’s comparatively small numbers, it is not obvious that we do. Industry pundits less enamored with Apple’s marketing savvy have wondered why one of the world’s most valuable companies opts to lose billions annually on a streaming service. The most common answer to date is familiar to the tech industry generally: TV+ loses money now to accumulate market share that it might monetize later. No doubt Apple does hope its streamer will become profitable; TV+ is one of a handful of “services” whose monthly rents, Cupertino hopes, will offset profitability declines in iPhone manufacturing. But whatever profits TV+ eventually generates will remain small relative to Apple’s overall business. And we miss the importance of streaming to that business if we assume we know the difference between “a show with product” and “a commercial.”

Apple has integrated its streaming and device businesses with unnoticed sophistication, in fact. TV+ programs don’t urge us to buy Apple products simply by making them visible. It’s not as if non-Apple media wants for scenes with iPhones and other Apple devices; they are the water in which we daily swim. Rather, TV+ imbues these ubiquitous objects with dynamic significance. It manages their cultural meanings and, by extension, the meanings of work, home, love, and family. That brand management is fundamental to almost every TV+ program. It’s not a superadded bug, a worm in an otherwise pristine apple; it’s the feature at the fruit’s core.

There is already ample testimony to Cupertino’s hands-on management of TV+ programs. Once there was “such a thing as an NBC-style comedy and an ABC-style drama,” said Ronald D. Moore, creator of TV+’s For All Mankind (2019– ), the year his show premiered. But he’d not given much thought “to the brand identity of the TV networks that aired his shows” until Mankind, which is a “match of theme and corporation” he’d never seen before. Apple CEO Tim Cook visited Mankind’s set, and Apple execs have been open, in an admittedly nebulous way, about their investment in TV+’s messaging. “When you’re not hiding behind lots of volume or lots of this and that, you’re saying, this is what we’re delivering to the world,” said Zack Van Amburg, co-head of Apple Worldwide Video.

What they’re delivering is a marketing machine, the likes of which we’ve never seen, one for which product placement inventories are wholly inadequate. The streamer delivers a world organized around Apple from the ground up. And that’s no less the case when the iPhone, above all, is physically absent but still very much implicit in a given program.

¤

Consider Apple’s Fingernails (2023), an ostensibly “independent,” self-consciously small 35mm film that evokes the Greek Weird Wave. Written and directed by Christos Nikou, the film depicts an Apple-free alternate present in which “love institutes” teach couples how to make their love stronger. Alarmed that people were no longer falling in love, scientists in this world invented a device to determine whether couples are, in fact, in love. The upside was supposed to be obvious, reports the institute’s brooding founder, Duncan (Luke Wilson), to a room of employees: “No more uncertainty. No more wondering if you’ve chosen the right partner. No more divorce.” But, he adds, the machine’s inventors did not anticipate “the fact […] that 87 percent of the couples that took the test received a negative result. It was a staggering statistic. Couples broke apart. And people suffered a great deal. And you’re all aware of the crisis that followed, the insecurity that this created in most couples.” People come to the institute, he says, “to take the risk out of love.”

The institute trains couples before administering the test. Like TV+, the courses are a device supplement—in this case, ones that educate in anticipation of a device’s future use. Paired lovers skydive to induce shared adrenaline rushes; submerge themselves in pools to induce breathlessness; undergo electroshock treatments to “associate the two pains” of a partner’s leaving and the shock itself; attend a romcom with Hugh Grant (“no one understands love more”) and then navigate a theater fire to “gauge” their “protective” instincts; and sing karaoke with French love songs, because French is “la linguage plus érotique.” The test itself requires removing fingernails by pliers and without anesthetic. This version of “the digital” requires a bruising sacrifice: if fingerprints open our phones, fingernails open our souls.

Training demonstration and test in Fingernails (Apple TV+)

The mysterious device that tests the nails—referred to only as “the machine”—looks like the love child of a 1990s microwave and a mainframe. Like Apple’s Severance (2022– ), Fingernails depicts a vaguely low-tech but mostly recognizable world, one in which corded phones, clunky TVs, and broken electric car windows establish the baseline against which a single, allegorizing invention stands out. In Fingernails, love is routinized not only by the lab-coated technicians working the machine but also by lost and lonely couples willing to undergo behavioral conditioning to secure a positive result. The film dropped on TV+ three weeks after Lessons in Chemistry (2023), which celebrates true love as if it were a bond between idiosyncratically compatible chemical compounds. Conversely, the quietly melancholic Fingernails mourns (and gently spoofs) love’s submission to the protocols of science.

The predictable problem it confronts is that, without risk, love enervates. Enter our protagonist, Anna (Jessie Buckley), who tested positive with Ryan (Jeremy Allen White) some years back. A recently unemployed schoolteacher, she is restless in her strifeless life. She applies for a job at the institute without telling Ryan, and there meets Amir (Riz Ahmed), with whom she falls in love. Or doesn’t. Having developed feelings for Amir, she retakes her test with Ryan and tests with Amir. She tests positive again with Ryan, whereas the machine appears to confirm Amir’s love for her, but not hers for him. She leaves Ryan for Amir all the same.

Anna and Amir in Fingernails (Apple TV+)

The machine might be wrong. Anna and Amir seem to be in love, and the film offers them a single straw at which to grasp: the machine malfunctions the day after Anna confirms her test with Ryan. But Fingernails is so effectively disquieting precisely because, for the most part, it commits to the machine’s accuracy; it refuses to offer itself as an alternative to that device, one able more effectively to register true love or its absence. Anna chooses risk and uncertainty, it would seem, at least in part because those qualities are incompatible with love. “Sometimes being in love is lonelier than being alone,” she says, presumably thinking of Ryan. It is unclear if life with Amir will make her less lonely, and Fingernails refuses to promise a happily-ever-after. Amir delivers the film’s last line as he dresses her finger wound: “This is gonna hurt.”

The machine is thus a technological device that enables a narrative device, which in turn enables the détournement of a familiar generic device, in which true love, forged in uncertainty and risk, triumphs over safety and complacency. The machine keeps Anna from true love, rather than delivering her to it, and, in so doing, estranges the audience from love and coupledom. But the détournement doesn’t entirely work. The film is keen to dispel love’s comforting illusions. Whatever this is between Anna and Amir, Fingernails appears to say, it might not be love as we know it. Still, the affective dynamics remain entirely familiar. The scenes Anna shares with Amir are electric; those she shares with Ryan are decidedly more lugubrious (the couple watches a documentary on caribou traversing barren tundra; Anna is bored while Ryan is moved to tears).

Fingernails might therefore be said to turn on a “gimmick,” where gimmicks are, following Sianne Ngai, “overrated devices that strike us as working too little (labor-saving tricks) but also as working too hard (strained efforts to get our attention).” Fingernails grows from a gimmick and is itself gimmicky, in part because the film’s machine does both too much and not enough. It lends an impossible objectivity to otherwise elusive emotions, and in so doing, the machine forces viewers to question what they think they know of love. But ultimately, however much attention the machine draws, and however much Fingernails wants to reject too-easy accounts of love, the film cannot but embrace cliché: truly real true love demands uncertainty and risk.

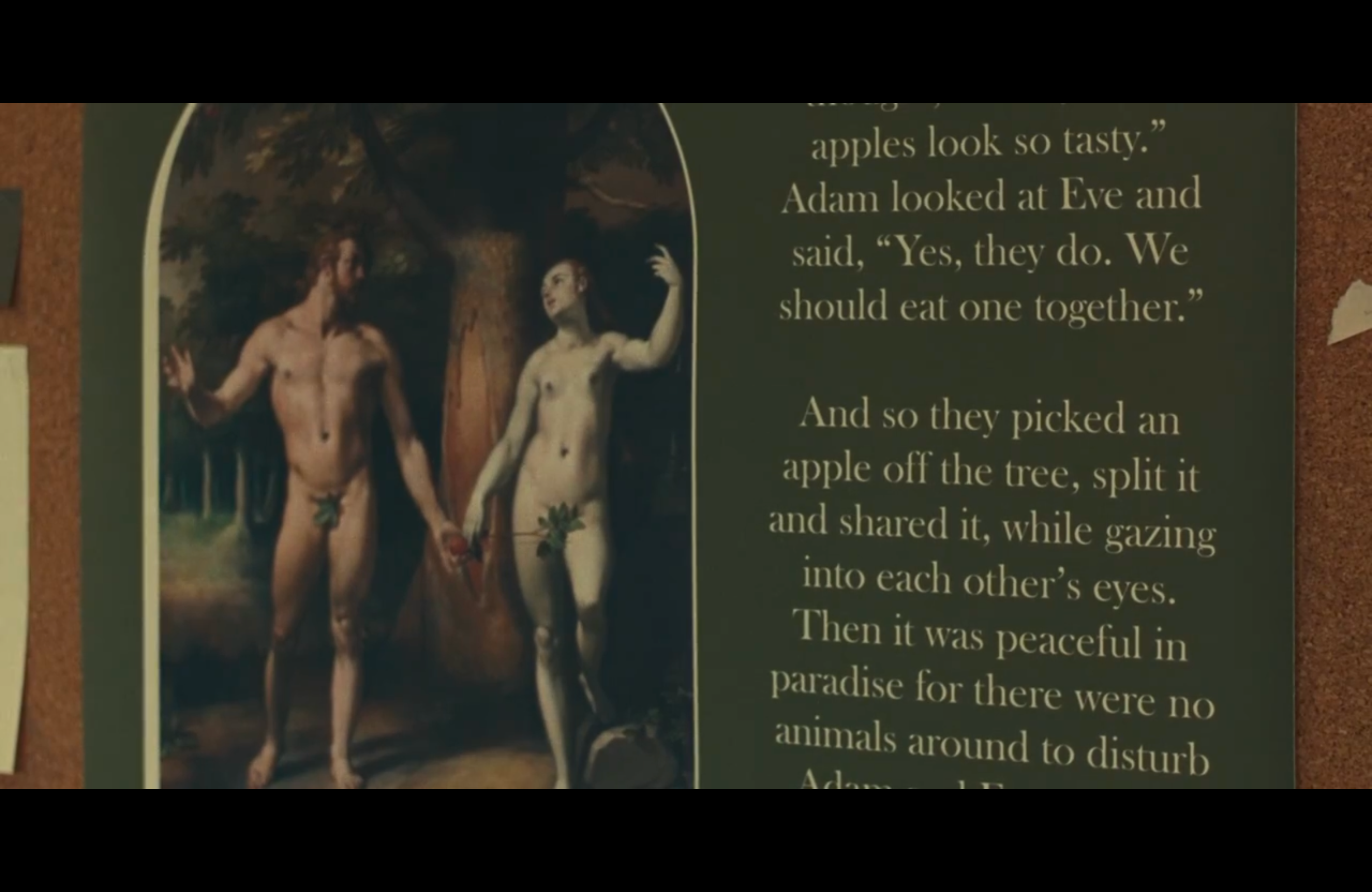

I’ll return to the love machine in a moment, but first, another gimmick. Fingernails begins with Anna applying for a job at an elementary school. We see through her eyes an inspirational poster that reframes the Garden of Eden story. Anna recounts the revision to Ryan:

[Eve] looked at the tree and said: “Wow, those apples look so tasty.” And he looked at her and he said: “Yeah, they do. We should eat one together.” So they picked the apple off the tree, split it and shared it, while gazing into each other’s eyes. And then—this is word for word—“It was peaceful in paradise for there were no animals around to disturb them or their love for each other.”

Ryan interrupts Anna, “That’s what the poster says?!” and adds, “I think that’s gone too far. I don’t think they should change a story that old.” Anna asks “Why?” before adding under her breath, “Did it even really happen?” We then hear a ringing phone and Anna traverses the length of the house to hoist a large, corded unit from the kitchen wall.

Fingernails Adam and Eve poster (Apple TV+)

Nikou’s first film was titled, yes, Apples (2020). The fruit plays a pivotal role, less as an emblem of sin than as a loved object of consumption that links an invented life to an actual one. The apple is no less crucial to Fingernails: the poster on which Anna reports explains everything to come. She lives with Ryan in an ersatz Eden; the “peaceful paradise” in which they consume is hollow without animality and, ultimately, the possibility of sin as the galvanizing uncertainty with which we all—readers, viewers, and Apple executives alike—must live.

¤

That is a story that TV+ tells over and over again. “Why does the serpent tempt Eve?” a daughter asks her father in Apple’s The Essex Serpent. “Well, it’s an allegory,” he replies. “The serpent is really the devil.” She responds, “That’s what I thought.” But the allegory is never that simple. Biting the apple is no more a mistake on TV+ than is the quest for knowledge. Apple’s first logo featured Isaac Newton, “a mind forever voyaging through strange seas of thought—alone.” A 1977 redesign evoked Eve’s forbidden fruit. That made sense for an upstart that wanted to make its computers—and later, the worlds that orbited them—beautiful and sensuous, the stuff of tactile pleasure as well as ease and efficiency.

Apples in The Essex Serpent and Dickinson (Apple TV+)

Forbidden fruits offer progress, which is why The Essex Serpent’s eponymous serpent “voyag[es] through strange seas” while auguring scientific enlightenment and women’s emancipation. The titular Emily (Hailee Steinfeld), in Dickinson (2019–21), complains: “I have to steal random bits of knowledge when no one else is looking.” Here again, knowledge promises sexual liberty, among much else, and in the pilot, Emily steals a kiss with her brother’s fiancée in an apple orchard. Apple’s inverted allegory of the Fall takes a slightly different form in Losing Alice (2020), Servant (2019–23), and The Changeling, each of which announces its interest in a Faustian bargain, which bargain, again, is never simply a mistake.

These narrative patterns are shortcuts that work hard, while working not nearly enough, to create coherence throughout TV+. Indeed, their ubiquity and salience save managerial labor: to recall Van Amburg, these patterns are Apple proclaiming: “[T]his is what we’re delivering to the world,” this is what we will buy. There’s less need for hands-on production oversight when Apple can buy a film like Fingernails on the festival circuit from a director like Nikou, whose first film might be said already to have Apple in mind, and who is certainly canny enough to learn from Apple programming what the company wants and doesn’t.

But there’s another, potentially more meaningful way in which Fingernails and Apple products mobilize the gimmick. For Ngai, the gimmick is “the aesthetically suspicious object as a ‘contrivance,’ an ambiguous term equally applicable to ideas, techniques, and things.” And her account is compelling because it allows us to link the thematic and more purely technical contrivances in Fingernails. If the love machine is a gimmick, that is at least in part because the film is interested thematically in what it means to work both too little and too much.

Anna initially thinks that working at the institute will improve her connection with Ryan. She discovers instead what might be a deeper connection, with Amir. But it’s less their interpersonal chemistry than the job itself, the film suggests, that creates that connection. The institute makes love a labor, which is what Anna wants. She rejects the machine’s conclusion (rather than the institute’s arduous exercises) because it would make being in love less of a job. After their second positive test, a frustrated Ryan asks, “What do you want? I think it’s normal to get into a bit of a routine. […] That’s the nature of being in a relationship.” To which she replies: “You can’t take it for granted. I think a relationship should be worked on every day. All the time.”

We might expect a positive test to superannuate that particular cliché. The machine confirms that Ryan and Anna share true love, so why should they self-administer electroshock therapy? Anna embraces the institute’s vision of love as round-the-clock labor not because her relationship outwardly requires it, but because she thinks it should. And so does Apple, as it happens.

¤

On TV+, love and work are almost always indistinguishable. Time and again, the vitalizing, saving enthusiasms of the calling unite otherwise separate spheres. On Ted Lasso (2020–23), Dickinson, Mythic Quest (2020– ), and Shrinking (2023– ), characters learn not just that loving work is an ethical, community-building imperative but also that there can be no true intimacy between families, friends, and lovers in the absence of that love. Distinctions collapse between home and office, labor and leisure. On Shrinking, Jimmy Laird (Jason Segel) breaks every psychiatric boundary. He takes a patient home to live with him and his daughter, and the three of them are transformed. Conversely, for three seasons, Ted Lasso (Jason Sudeikis) will be present to his son only on Apple devices, because being a good father requires and follows from fidelity to his more primary passion, coaching. When those priorities change, the comedy ends.

Apple’s dramas are no less committed to the primacy of work. In WeCrashed (2022), Rebekah Paltrow (Anne Hathaway) tells Adam Neumann (Jared Leto), “Do what you love. That is how you win the game of life.” Following her advice, he conceives WeWork as a love-addled fusion of labor and leisure. “I want you to meet your wife here,” he pitches one client, “maybe even fall in love,” he pitches another. On Lessons in Chemistry, Elizabeth (Brie Larson) and Calvin (Lewis Pullman) fall in love working in a lab; after he dies, she moves the lab to her home’s kitchen. Severance might seem to indict endless drudgery but ultimately indicts too-stark divisions between work and the rest of life. And The Morning Show, which began as an ostensible think piece on the #MeToo movement, struck many, reasonably enough, as a roundabout defense of workplace relationships.

Fingernails might feel gimmicky, by these lights, because it strains on behalf of extrinsic ends—in this case, TV+’s systematic collapse of work and nonwork. But that collapse, it is crucial to see, exists in the service of still another gimmick, Apple’s ultimate gimmick: the iPhone. For Ngai, the gimmick makes “dubious yet attractive promises about the saving of time.” Dubious because contradictory at its core—while the gimmick pretends to eliminate labor, on behalf of an easier, more leisurely life, it actually “regenerates the conditions keeping labor’s social necessity in place.”

Is there a more culturally significant gimmick, defined this way, than the iPhone? Political philosopher Jason E. Smith asks, “Where does the iconic technological artifact of our own crisis decade—the Apple iPhone, first offered to the U.S. public in June 2007, on the very eve of the economic meltdown—fit into [automation’s long history]?” Does the smartphone, so seemingly revolutionary, actually increase our productivity? It does not, Smith says. Rather, it confirms economist Robert Solow’s famed dictum: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

For Smith, the iPhone is a consumer-facing device that creates off- rather than on-the-clock efficiencies. It helps us with everything but work, and in so doing, it allows for the quantitative rather than qualitative expansion of the working day, for more work rather than more efficient work, in other words. Accordingly, we might say that the iPhone works both too little and too much on behalf of work itself. It saves labor only by radically expanding labor’s purview. If our devices facilitate a working day that never ends, they also personalize that day, Apple whispers, and make it beautiful, worthy of love. That is the gimmick to which TV+ and Fingernails commit.

It is tempting to imagine Fingernails rejecting not simply its love machine but technology generally. The absence of computers and smart devices renders love’s routinization quietly uncanny; bereft of distraction and stranded where and as they are, characters have no choice but to face the muted tones of their naked, unadorned lives. But there is no love institute and no personal transformation for Anna without the machine—which compels her to work harder. Ryan refuses to attend the institute; he doesn’t see the point. Conversely, Anna needs love’s labor and the machine—to test herself against its certainties. While her final choice rejects the machine’s conclusions, whatever transvaluation of love that choice represents is owed to the machine’s prompting.

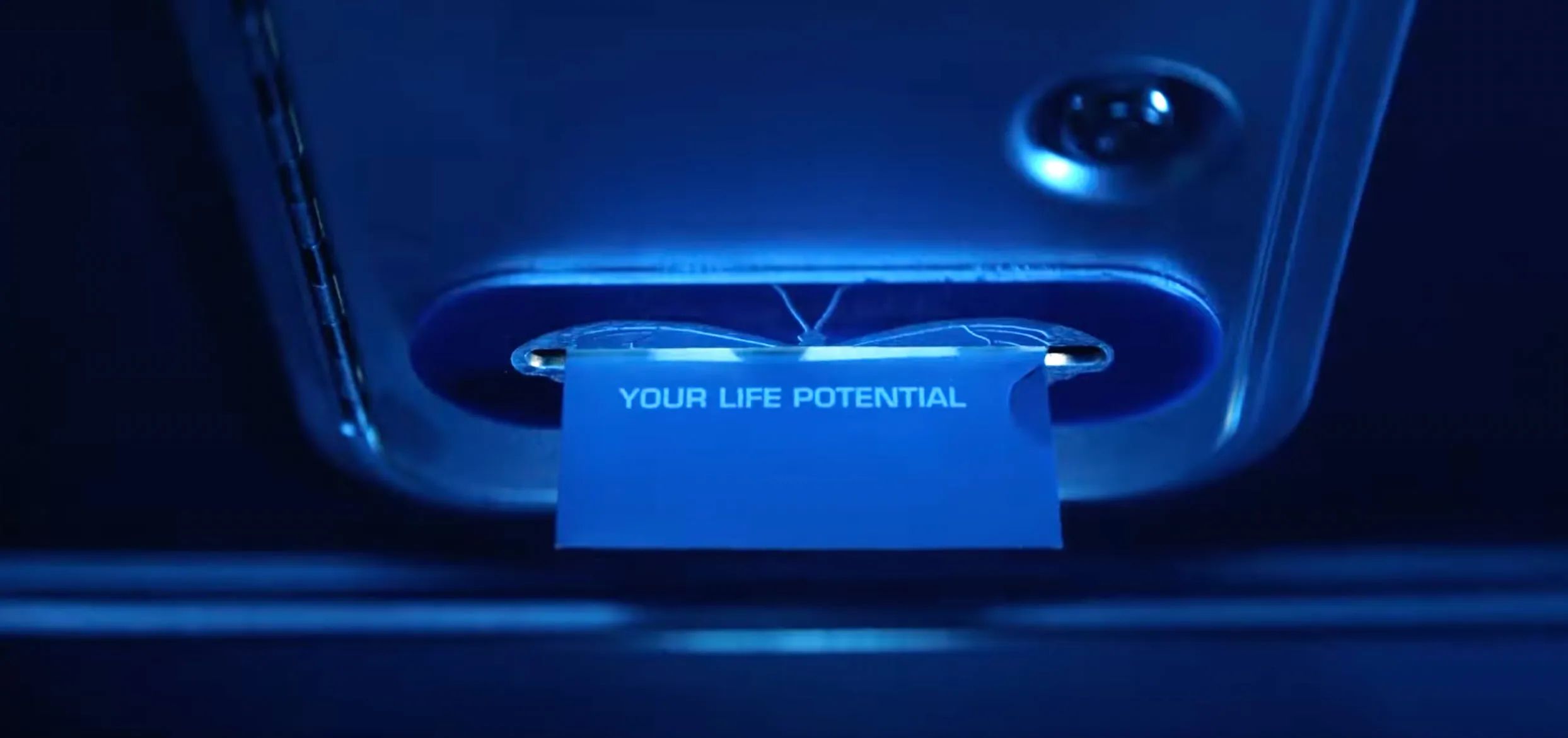

The machine thus serves Fingernails as the “Blue Morpho” machine serves Apple’s The Big Door Prize (2023– ): as a gnomic black box, whose inner workings we cannot fathom, that works both too much and too little on behalf of personal metamorphoses. A mysterious device (whose logo echoes the “Monarch” logo in Apple’s Godzilla reboot) appears in a small town. It distills a user’s “life potential” by naming the calling to which each is best suited: “superstar,” “dancer,” “male model,” “healer,” “royalty.” These are not simply jobs; they are life missions, expressions of love, tasks to which individuals are called (as if on their phones!).

Embracing a calling is risky, and the machine sows self-doubt. Anticipating Fingernails, a cautious schoolteacher tests his convictions against its account of his life. That process is transforming, not because the machine is infallible but because it forces him to reinvent himself. “I think I have everything I ever wanted,” he tells a friend, who replies, “Maybe you didn’t want enough.” And maybe you have not been working hard enough. The schoolteacher’s imagined happiness amounts to another false paradise, the Blue Morpho machine, another apple promising new horizons.

Again echoing Fingernails, the first season concludes with the once-coupled breaking apart and embarking on arduous voyages of self-discovery. They will learn to love traveling “strange seas of thought—alone.” The work will set them free.

Blue Morpho machine in The Big Door Prize (Apple TV+)

LARB Contributor

Michael Szalay is a film and television editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books. He teaches at UC Irvine and his most recent book is Second Lives: Black-Market Melodramas and the Reinvention of Television (Chicago, 2023).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Yacht, Rocks: On HBO’s “The White Lotus” and Picturesque Dread

Jorge Cotte reviews HBO’s “The White Lotus.”

Going Klear: A Glass Onion Franchise in the Wild

J. D. Connor asks why Netflix spent $450 million to acquire the “Glass Onion” franchise.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!