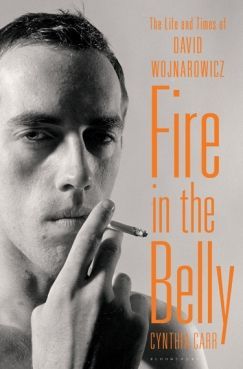

Fire in the Belly by Cynthia Carr. Bloomsbury USA. 624 pages.

CYNTHIA CARR OPENS Fire in the Belly, her biography of David Wojnarowicz, with a story about the artist as a child of six or seven running through the streets, "giddy with what he'd just learned. 'We all die! One day we will all be dead!' As he told his friends," Carr writes, "they burst into tears, parents rushed out of their houses and David was seen as a very sick little kid." This was a story he liked to tell about himself. He also told one in which he was a street kid surviving by his wits, a child runaway, and then a Times Square hustler. In one story he is a truth-teller, in the other he is an outcast; both are important to Carr's biography, as primary scenes in the artist's mythology.

Fire in the Belly goes on to map the full arc of Wojnarowicz’s life and work, placing each carefully in context. Carr's book is a frank, emotionally powerful oral history of New York's downtown scene during its best years (the explosion of experimental art spaces in the early 1980s), and its worst (the plague years which followed).

The book's architecture is provided by the recollections of the artist’s community — the voices of the people who knew him animate Carr's writing. But Fire in the Belly's spirit comes from Carr's feel for the cosmology of Wojnarowicz's work, and for the poetics of his writing. She describes the latter as a "Howl," "built on the long breath that leaves one body to engulf the endless world and, returning, sees the universe in a single action."

Wojnarowicz was one of the most influential writers and artists of his generation, and his biography plays an important role in his work. As Carr writes it, "David has been called everything from 'the last outsider' to 'the last romantic.'" She explains that writing about him meant "dealing with what [his friends] called 'the mythology.'" Where his friends seem to use that word to describe the distance between the artist's self and his self-fashioning, Carr opens that mythology up to include the way that his life and his work operate as an emblem for the end of times — for the end of the underground, for a generation wasted and traumatized by AIDS.

His visual work bodies forth the post-punk DIY street sensibilities of the 1980s. With Peter Hujar, Karen Finley, Marion Scemama, Kiki Smith, Richard Kern, Tommy Turner, James Romberger, Marguerite Van Cook, Keith Davis and Dean Savard (to name just a few of his collaborators), David Wojnarowicz participated in communal conversations about art and survival on the social and economic margins of the Reagan era.

The class antagonism of the period plays a big part in Wojnarowicz’s story as well. Carr writes, "This was someone who never went to art school, who barely finished high school, who never owned a suit, a couch, or (until the last two years of his life) a credit card." His friendships sustained him in ways that his queer and anti-capitalist work could not. Although by the mid-eighties he would just about survive from his art (and give much of what he earned to the people around him), he was caught in censorship fights soon after.

The relationships that saw him through his roughest periods were routinely tested by outbursts of rage, fits of paranoia. He felt like an alien, and kept whole sections of his life separate from each other. Although in writings and interviews he liked to offer a picaresque timeline of his life as a runaway and hustler, Carr writes "that wasn't quite who he was." Things in that story, Carr explains, are a few degrees off. He didn't leave the house at the age of nine, as he often said, but later. And the circumstances behind his leaving were complicated. His autobiographical tales were just separate enough from his life to give him a buffer zone.

Carr shows that no one in his family was eager to hold onto their recollection of the past. She puts the situation to us plainly enough: it was an abusive and unstable home. "Childhood was painful to resurrect for David's brothers and sisters, including his half-siblings [...] all but Pat [his sister, with whom he was close] cried at some point while talking with me, and Pat had big holes in her memory." His "family was beyond dysfunctional. It was shattered." For Carr, the point is not just to reveal the facts behind the myths (exactly what year did he leave home, and under what conditions), but to ask what benefit, artistic or otherwise, those personal mythologies gave Wojnarowicz, and those around him.

¤

The David we encounter in Fire in the Belly is a composite figure. The voices of his circle are woven together, and in some cases Carr deploys them gently against each other. This gives us a glimpse of Wojnarowicz's romantic revisions of his own history. Take, for example, Wojnarowicz's recollection of his first encounter with boyfriend Jean Pierre Delage. He wrote that he'd first seen Delage while he was out cruising in Paris. He saw "'a stranger leanin against the mid-night doors of the Louvre.'"

"'Actually,'" Delage tells Carr, "they met 'in a bush.'" Carr pulls together a narrative of the history of that relationship (they corresponded for the rest of Wojnarowicz's life). Where Wojnarowicz might have represented their romantic relationship as over, or as on the verge of being over, and where others might recall this as the case (perhaps remembering the impression that Wojnarowicz gave them), Delage is quietly insistent throughout the book that however the nature of their relationship was revised, they "'never broke up.''"

The David in this book is the David remembered by his siblings (vulnerable, drawn to animals and insects), the David that Peter Hujar fell in love with, the David whose heart was melted by Tom Rauffenbart (his partner of seven years to whom Carr dedicates the book). This is the David who itched to go on road trips with friends, but who scarcely ever took one along without kicking him or her to the curb. It's the David who asked Karen Finley "What is sexuality?" in the middle of hours-long conversations about the relationship between childhood abuse and precocious sexuality, between friendship and love.

Fire in the Belly describes the emotional complexity of Wojnarowicz's relationships with women like Karen Finley, Kiki Smith, and Marion Scemama.* His friendship with Scemama was particularly complex, characterized by a fierce attachment (from both sides) that cycled through rejection as each searched for something impossible from the other. When they weren't each other's muse, they were each other's disappointment. One would feel rejected; the other would feel like a failure. Rauffenbart thought "she was trying to swallow him." Scemama thought Wojnarowicz used her to make Rauffenbart jealous. Wojnarowicz felt that too much changed when Hujar died, when everybody started to die. Scemama wanted to be there when he died. She wanted to take photographs of his body the way he had taken photographs of Hujar's. She was devastated when she realized this was impossible and she clearly didn't understand why.

The interface of sexuality and friendship is on full view across the whole of Carr's book: the two are not separable. His relationship with Peter Hujar — perhaps one of the great love affairs in American art history — developed from a sexual connection into a profound romantic friendship. Desire was unevenly distributed between them; Hujar felt more for Wojnarowicz than the younger man felt for him. But Wojnarowicz would also tell Tom Rauffenbart, his boyfriend and quite clearly one of the great loves of his life, that in order of importance Rauffenbart came third, after his art and then Hujar. And Wojnarowicz would experience profound grief and depression on Hujar's death —this was the loss of a lover, but also a father figure and mentor.

.jpg) David Wojnarowicz: Peter Hujar Dreaming/Yukio Mishima: St. Sebastian (1982)

David Wojnarowicz: Peter Hujar Dreaming/Yukio Mishima: St. Sebastian (1982)

But Rauffenbart was his boyfriend — his partner. The chapter narrating their initial months together is an exhilarating read. At the end of a romantic weekend, Rauffenbart told Wojnarowicz that he was falling in love with him: "David said nothing. His eyes filled with tears and turned red. He looked away." He tells Carr, "It was fine with me, that response. I remember his whole face went into shock."

The David in Fire in the Belly is also the David that Carr knew herself. (Of her first encounter with him, Carr recalls, simply, "He was a force, and made a strong impression quickly.") Wojnarowicz's world was hers. As a journalist, Carr covered many of the exhibits and performances chronicled in her book. She also conducted a series of interviews with Wojnarowicz for a 1990 Village Voice cover story.

She places herself so gently in the scene that by the time I arrived at the book's devastating final chapter, I'd become lost enough in what was happening I'd forgotten that Carr was one of Wojnarowicz's caretakers during the last months of his illness. I'd forgotten that one of the Davids we would get to know is the one who got sick and died.

¤

In 1990, the New York gallery Artists Space hosted Against Our Vanishing, an important group show about AIDS curated by Nan Goldin. Wojnarowicz’s catalog essay, "Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell," tripped a number of alarms. It was his words about Cardinal O'Connor, however, that caused the real problem:

This fat fucking cannibal from the house of walking swastikas should lose his church-exempt status and pay taxes retroactively for the last couple of centuries [...] This creep in black skirts has kept safer sex information off of the local television stations and mass transit spaces for the last eight years of the AIDS epidemic therefore helping thousands to their unnecessary deaths.

The gallery's executive director saw that this language directly challenged the recently passed Helms amendment which prohibited the use of federal funds to support art depicting homosexuality or which exhibited a clear political message. He was asked to revise the phrase "fat fucking cannibal." Goldin tells Carr "the only thing he agreed to do was take the word 'fucking' out."

The show was supported with NEA funds granted before the law had passed. Nevertheless, Wojnarowicz’s essay was passed over to lawyers, and also to the gallery's board for discussion. Carr shares the astonishing result: Artists Space asked Wojnarowicz to sign a liability waiver, "assuming financial responsibility for all 'losses, liabilities, damages, and settlements' resulting from his essay." After talking to a civil rights group (which agreed to defend him, if it came to that), he signed the papers. The gallery agreed to publish his writing, but it also avowed its desire to avoid taking responsibility for doing so. For them, it "felt like the whole future of public funding of art [had] come to rest on [their shoulders]." They also renegotiated the grant so that it would not subsidize the publication of his essay. By this point, his name was routinely invoked in debates about AIDS, sexuality, and contemporary arts funding.

The vulnerability of Wojnarowicz's work to political assault has remarkable staying power: Carr takes the title of her book from Fire in my Belly, an unfinished film that was included in a 2010 exhibit of lesbian and gay portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery (Hide/Seek: Desire and Difference in American Portraiture). The work was removed after the museum was sent one letter of complaint by a marginal extremist religious organization.

Although censorship battles are a significant aspect of Wojnarowicz’s exhibition history, the controversy they’ve produced eclipses his work's complexity and leaves little room for thinking about what kind of person he was, and why his art is so utterly compelling.

¤

Wojnarowicz stood at the busy intersection of New York's gay underground and the Lower East Side art scene. His work, emblematic of the energies of both worlds, also seems to anticipate what happened to them. What happened was a compound disaster: the realization of "urban renewal" projects of the 1960s as well as the commercial capture of the underground in the 1980s; homophobic indifference to a pandemic that seemed to target that very underground. The relationship of these stories to each other would become the explicit subject of Wojnarowicz’s later work and they figure as integral parts in Carr's account of his life.

The late 1980s and early 1990s marked the transformation of New York City's downtown from counter-cultural space to neo-liberal playground. Carr writes,

David was a major figure in what is now a lost world, in part because he came along at a time when New York City was as raw as he was. Manhattan still had uncolonized space: from the rotting piers along the Hudson River where gay men went for sex to cheap empty storefronts in the drug-infested East Village. There, in what David called 'the picturesque ruins,' so much seemed possible and permissible.

Possibility and permission are revised over the course of Carr's biography. In New York, it was once possible to cultivate a difficult but generatively creative life on poverty's edge (one chapter is devoted to "The Poverty of Peter Hujar"). It once meant that as an "outsider" one could remain illegible to the mainstream and its regulatory impulses and find a certain freedom in that (although that liberty could be modulated by bitterness, rage and paranoia — Carr does not romanticize this side of things). That was all "before gentrification flattened our options, and AIDS changed the world for the worst, and congressional leaders started weighing in on artists who filmed ants. We had no way to know how much was ending." For a brief moment, New York's blight produced zones of intense experimentation. Galleries and performance spaces like Gracie Mansion and Civilian Warfare opened in urban no-go zones and they dedicated themselves to all the things that the official art world couldn't be. Artist occupied crumbling buildings; they enjoyed autonomy among the city's ruins.

The piers were torn down and rehabbed into sports complexes. People showed up on the Lower East Side looking not (only) for the drugs for which the neighborhood was infamous, but for a cool scene and a hot art acquisition. And a real estate opportunity. This is the background against which Wojnarowicz's story unfolds: "the whole concept of marginality changed," Carr writes of this cultural shift, as his generation became "'hot bottom' of the torrid art market." Populism morphed from an anti-elitist politics to a mass marketing strategy.

In navigating these dark turns, Wojnarowicz learned a lot from Peter Hujar. The older artist was totally uninterested in doing anything but his own work. He had a reputation for being "difficult" and could not sustain a commercial practice. Stephen Koch describes Hujar as the "poorest grown-up" he knew.

Wojnarowicz was younger than Hujar: his contemporaries included Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Zoe Leonard, Kenny Schaarf, Cookie Mueller, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Nan Goldin. His art was part of the hyped club-to-gallery circuit that defined the 80s (Wojnarowicz worked at the original Danceteria with Leonard and Haring.) Unlike Paul Thek, Jack Smith and Hujar, these artists developed their practice alongside shifts in the relationship of counter-culture to market-culture. Most, including Wojnarowicz, worked with a pop vernacular: Haring and Basquiat's graffiti, for example, as well as their conversation with hip-hop, the cheap plastic sensibility of Schaarf.

But where Haring’s and Schaarf's work has the capacity to circulate within mass and pop culture, and where Basquiat's paintings have the capacity to be absorbed into the halls of the museum, Wojnarowicz's work has been much more resistant to popularization and also to canonization. His output has the intense political spirit of artists like Sue Coe, Nancy Spero, Leon Golub and his friend Karen Finley — none of whom are easy to place. Finley draws the distinction between Wojnarowicz and some of the others from their circle: "We both felt that coming to the East Village and creating work came out of a different need than it did for other artists, like if we weren't creating the work, we would be going crazy."

This might read as naive, or cliché. But then think about Finley's career — it isn't Marina Abramovic's.

When his friends took him in a wheelchair to see Finley's installation, Memento Mori, at The Kitchen in 1992, it would be Wojnarowicz’s last outing to look at art. The show was demanding: different rooms addressed AIDS, grief, violence against women and abortion. Finley remembers that he participated in the whole exhibit. "It broke my heart when I saw him reading everything on the walls. He was almost unable to walk." This kind of work mattered to him: Finley (also targeted by the right) was a fellow traveler.

Wojnarowicz participated in some of the most influential exhibits of the eighties. In that decade, he made work inside the dilapidated piers, formed a band with friends (Three Teens Kill Four) and put out an album. There were multiple productions of Sounds in the Distance, a theatrical piece built on a suite of his monologues. He was part of an exciting constellation, exhibiting with multiple galleries (e.g. Civilian Warfare, Gracie Mansion, PPOW and Pat Hearn) and his work appeared in group exhibits through the decade. He had two pieces in the 1985 Whitney Biennial, appeared in Life Magazine, and then hit a professional and emotional wall. He was not comfortable with selling his art to collectors, and as Carr tells it, he was also not entirely happy with the work itself. A productive period was followed by a fallow one. But if "he could not walk easily into his own success,” that success did give him a new zone from which to explore the work of maintaining a critical engagement with the world. His practice shifted — he worked more and more with film, photography, installation and performance.

In the span of just a few months in 1989 and 1990 his art would figure in multiple censorship battles. The American Family Association set its sights on Tongues of Flame, his retrospective at Illinois State University. The AFA excerpted sexually explicit details from the exhibition’s catalog and asserted that the federal government was subsidizing porn. Wojnarowicz fought back by charging the organization with the misappropriation and misrepresentation of his work. A judge found Wojnarowicz in the right, but he was only awarded $1.00 in damages. Many would say it was a Pyrrhic victory, but for him it was a win.

When the art world rallied around Wojnarowicz in 2010 and protested against the Smithsonian's behavior, there was an echo of past battles, fought by people like Wojnarowicz and Finley, by Holly Hughes, Tim Miller and Andreas Serrano. But frankly, that war was lost in the mid 1990s. The magnitude of that loss can be seen in the weakness of the engagement of Wojnarowicz's work in the stands people took against its censorship. With the exception of blog posts by his friends (James Romberger's is notable), the defense of his art was staged independent of any discussion of its genuine difficulty or even its value. The most meaningful discussion of his actual practice was offered by Art in America, when it republished a 1990 essay on him by Lucy Lippard ("Out of the Safety Zone" [1990]).

It is almost as though the complexity of discourse about Wojnarowicz’s art disappeared when he did. Fire in the Belly will go a long way towards correcting that.

¤

If as a child David Wojnarowicz was compelled to broadcast the news that we all die, as an artist he was captured by time. Across a wide range of mediums he would meditate on time as a narrative structure (imposing beginnings and endings), on the binding of experience and time, and on the simultaneity of the forward motion of time, and history's backwards glance.

In 1989 he created an emblem for himself: a painting of dinosaur with his name written across its spiny back (Something from Sleep IV). One Day This Kid frames an image of a young boy with text that describes growing up as a queer kid in a homophobic world: it forecasts a terrifying future. A painting from 1986 and an undated poem share versions of the same title, "History Keeps Me Awake Some Nights." The poem concludes,

we have come out of our mothers bellies

to find ourselves at the end of ropes

strange how this sleep overtakes us

how we move sideways as our love dies

how you were once some guy

who knew neither my present or my past

whose eyes and hands worked in silence

as you turned me over and over

in the dim light of dusk

removing articles of clothing

watch these wet bodies on the sheets

watch how they slowly become history

ITSOFOMO (In the Shadow of Forward Motion), his most fully realized cinematic project, is all about time — feeling its movement, feeling life unfold as the future's shadow. Deep into the hour-long montage, his voice intones: "When I put my hands on your flesh I feel the history of that body. Not just the beginning of its forming in that distant lake but all the way beyond its ending." Those words are also printed across a photograph of skeletons in an Indian burial ground — When I Put My Hands on Your Body (1990), one of the last works he ever made. Time is conceived of as a serpent's tail. The ancient and the future meet in the flesh and bones of the present.

It is tempting to explain Wojnarowicz's preoccupation with time as a response to the AIDS crisis. But Carr's biography makes clear that this was an early part of his thinking. Perhaps it is more nearly the case that Wojnarowicz could be so compelling on the subject of AIDS precisely because he'd been thinking on the order of life and death for so long.

It has now been 20 years since David Wojnarowicz died from AIDS. It's cruel how the disease takes over the way we remember him.

This is the point I keep returning to, in thinking about how much Fire in the Belly moved me. In the text, AIDS first appears as a poorly understood problem. People important to Wojnarowicz's story disappear for months. They resurface, gaunt and disfigured and then disappear for good. Before you know it, it's everywhere. The book's structure mirrors the pace of the pandemic: it creeps into the narrative and soon we are all underwater. Carr, in her deeply personal book, written in almost Spartan prose, tracks the disappearance of whole worlds.

But you can't take the full measure of that loss by staring into a void.

Carr has written an intimate portrait of Wojnarowicz's struggle, even as the walls were closing in on him, to establish an understanding of his way of being in the world. Fire in the Belly honors Wojnarowicz's vitality and passion, and that of his friends and all his lovers, too. It's in the details. Like how when he met someone he liked, he would note in his diary, simply, "met a fella." Written by someone who was there, and isn't afraid to show us what that meant, this story is framed by disaster, but with a fierce tenderness in the writing — an attention to little things that would fall apart under less expert hands.

* It’s hard to read Fire in the Belly and not think of Just Kids, Patti Smith's recent account of her friendship with Robert Mapplethorpe. Their attachment to each other was profound: it was romantic and sexual until Mapplethorpe came out and developed relationships with men. Smith and Mapplethorpe eked out an existence together in New York in the late 1960s and early 1970s; they bonded over their affection for Rimbaud (also one of Wojnarowicz's muses), and moved through New York's various underground scenes until one found rock and roll, and the other found photography. Just Kids is framed by Mapplethorpe's death: the memoir opens and closes with the moment Smith learns that her friend has died.

Recommended Reads:

LARB Contributor

Jennifer Doyle is the author of Sex Objects and Hold It Against Me. She teaches at the University of California, Riverside.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!