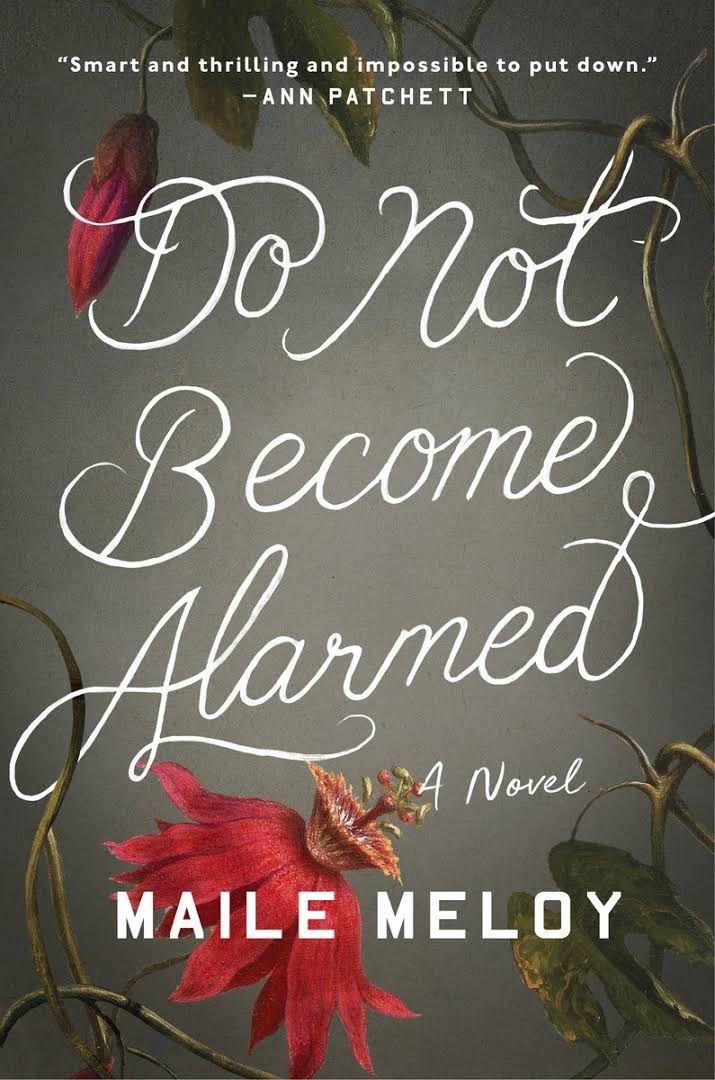

An Account at the Heartbreak Bank: On Maile Meloy’s “Do Not Become Alarmed”

Jean Hey can’t put down “Do Not Become Alarmed,” the latest novel by Maile Meloy.

Do Not Become Alarmed by Maile Meloy. Riverhead Books. 352 pages.

PART OF THE CLICHÉ of the American abroad — that fleshy fellow munching a Big Mac in Paris — is that under his extra-large sweatshirt and baseball cap lies a deep suspicion of all things foreign. Perhaps the vastness of the United States is to blame, or the fact that English is the only required language, or our super-power status and relative wealth, but as a nation we are pegged as nervous travelers, suspicious of the water and the weird food and the taxi driver with the unnaturally wide smile who has surely noticed the bulging money belt strapped to our waist. When traveling with children the suspicion can easily turn darker, more visceral — slip into something closer to fear. Because who knows what a child may put in her mouth? Or to which colorful, beckoning stranger she might succumb?

It is this fear that Maile Meloy mines in her third non-YA novel, Do Not Become Alarmed, in which two couples take their four children on a luxury cruise around Mexico and Central America. The ship is “like an enormous white layer cake, or a floating apartment building,” and its endless buffet and swimming pools offer everything they could want, including not having to step on third-world soil.

The couples — Liv and Benjamin, and Nora and Raymond — are affluent, fortysomething, and live in Los Angeles. The women are best friends and cousins whose lives have always been entwined. The trip is Liv’s brilliant idea. Never mind that she considers cruises tacky and an environmental nightmare; her cousin Nora is mourning the recent death of her mother, and a cruise over Christmas will offer the perfect diversion. Besides, it will give the adults respite from the kids, who will be fed and entertained and, presumably, kept safe.

Meloy deftly shifts point of view from one person to the next, giving voice with impressive authenticity to 13 characters. The strongest voice belongs to Liv, a hard-working movie executive. She carries the most chapters, including the first and last, but, more than that, she presides over the whole through sheer force of personality:

Liv was pragmatic, a problem-solver. She got it from her mother, a flinty Colorado litigator. She believed in finding a third way, when the options seemed intolerable, and she believed in throwing money at problems, when it was possible.

Liv is responsible for introducing Nora to her dashing African-American husband, Raymond, a minor movie star known for playing an astronaut. Liv also encouraged Nora to send their kids to the same school as hers. Nora even gives Liv credit for running her life better than she could possibly do herself.

Once on board, Meloy wastes no time foreshadowing the disaster to come. By page four there is mention of the Titanic, by page 10, the characters are wrapped in Raymond’s bedtime reading of murder and pirates in Treasure Island. More immediate rumblings come in the form of an illicit documentary on the in-room television. Instead of the advertized video about the ship, the workers are telling the camera their stories of exploitation, thwarted ambition, and the longing to see their children. All of which makes Liv feel they are likely to be hit by the karmic bus to even the score. The disaster, she believes, “will be the thing you don’t expect. So you just have to expect everything.”

A glamorous Argentinian family tells them that they, too, have seen the video. The silver-haired father, Gunther, whom Liv can’t look at without thinking of Nazis, comments, “If there is class war on this ship, I am telling you, we are outnumbered.”

At this point Meloy introduces a subplot and shifts the setting to a village in Ecuador. We meet 10-year-old Noemi, who is about to be sent away because her grandmother can no longer afford to keep her. A stranger — a tattooed man named Chuy — is to take her to New York where her parents now live. Noemi hasn’t seen them in two years and doesn’t want to leave her village. She thinks her grandmother might have allowed her to stay if a 12-year-old girl on their street wasn’t having a baby and a nine-year-old boy hadn’t been shot and killed in front of her. She obediently sets off with the gruff but kind Chuy and with her only friend and confidant: the stuffed pig that Chuy has given her for Christmas.

The contrast between the cruise-ship children and Noemi is obvious: rich Americans who take their privileges for granted versus poor immigrants willing to risk all for a chance to reach Nueva York. Inevitably, hundreds of pages later, Noemi and the American children are thrown together, violently, and the meeting changes the trajectory of their lives.

With Noemi launched on her journey, we return to the boat, where Liv has decided that the perfect antidote to the children’s post-Christmas boredom is to take a zip-line tour of a rain forest. They are now docked in “the Switzerland of Latin America,” presumably Costa Rica, and Liv (whose name means “protection” in Norwegian) assumes this means they will all be safe, or at least not beheaded or killed by food-borne pathogens, which she has heard happens in Acapulco, the previous stop. She also realizes that their leaving the ship would give Perla, their Filipino stewardess, an opportunity to call her children:

Every time Liv saw a stewardess plumping pillows in an open cabin, she was stunned by the heartache of it. Never seeing her kids. Missing out on the tiny changes, the lost teeth, the dawning look of some small discovery on their faces. Making strangers’ beds while your children learned to read. Perla didn’t need praise for her towel-animal skills or questions about her kids’ ages. She needed Liv to get out of the cabin so she could get her work done early and call home.

Reading this we can’t help but think of Noemi and the milestones in her young life that her parents have missed. As the American children get ready for their zip-line tour, buoyant at the prospect of this artificial adventure, we are reminded of Noemi for whom adventure is only too real.

The men, it turns out, are not going on the zip-line tour. Gunther the Argentinian has planned a day of golf in the city and invites Benjamin and Raymond to join him, leaving his wife and two teenagers to go with Liv, Nora, and their offspring. On the way to the zip-line a tire bursts and the van crashes into an oncoming car, sending Liv into a frenzy of protection as she struggles to reach her crying children. Everyone is okay, and instead of waiting for hours to be picked up, the tour guide leads them through the undergrowth to a beach. The setting is idyllic and the water seems perfect — calm, protected, safe for all swimmers — and the children wade off. And here, Liv’s prediction proves correct: the disaster is the thing you don’t expect. The horror that confronts Nora and Liv on that beach isn’t any of the possible calamities they have contemplated. It is simply this: one minute the children are there, and the next they are not. Nora, fresh from seduction by the smooth guide, turns to him and asks — or rather, screams — “Where the fuck are my children?”

That question fuels the remaining 300 pages of the novel. Meloy has set up her premise with great dexterity, but the bigger feat is to make us care about the answer. Six spoiled children are lost in a strange country and their entitled parents are in a state of anguish. So what? Yet not only do we care sufficiently to turn the pages, but Meloy also has us worrying about every single one of these people — including the child who always has to be right and tells everyone what to do; including the Argentinian mother with expensive-looking plastic surgery and the actor whose only knowledge of crime is playing cops in movies; and including, most definitely, the litigious Liv, whose instinct is to argue and bait and sue the cruise line for all it’s worth. With each chapter Meloy immerses us in a different character’s point of view, constantly upping the stakes, changing the angle of our vision, and, in the process, unfailingly surprising us and stirring our sympathy. We come to understand that these people who fret about imagined disasters on strange shores are also funny and ambitious, clear eyed and caustic, and when things go from bad to worse, as they inevitably and tragically do, they are quick to blame each other, certainly, but no less than they blame themselves.

At times the novel hovers close to melodrama — the plot involves drug lords, a fatal car chase, several murders, and a child in diabetic shock — but two ingredients save it: characters that are fully rendered and original, and writing that is beautifully spare and understated. In fact, its gripping plot, breezy style, and lean prose may persuade bookstores to place Do Not Become Alarmed on the shelf reserved for “beach reading.” Which would be a pity, not because it can’t be enjoyed with a soundtrack of surf, but because while feeding us high drama, Meloy also encourages serious reflection — on race and privilege, sex in marriage, what it means to be an American, the innate resilience and resourcefulness of children, and particularly, on the limits of parental power.

Liv and Benjamin’s son almost died soon after he was born, and at the time Liv recognized that she and Benjamin were now wedded not only by marriage but by the terror of losing a child. “To have a child is to open an account at the heartbreak bank,” Liv said. She just had no idea how big their payments might be, nor how devastating the toll.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jean Hey was a journalist in South Africa before immigrating to the United States. Her essays have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Plain Dealer, Chicago Tribune, Solstice Literary Magazine, The MacGuffin, and Arrowsmith Journal. She holds a dual-genre MFA in fiction and nonfiction from Bennington College and recently completed a collection of memoiristic essays about immigration and identity.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Wanderer’s Journey: On Eileen Battersby’s “Teethmarks on My Tongue”

Jean Hey reviews “Teethmarks on My Tongue,” a coming-of-age novel by Eileen Battersby.

Love and Loneliness: Adult Authors of Y.A. and Children’s Literature

'Serious' authors who have written Y.A./Children's lit

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!