Alive in a Magic Democracy: On “The Real Lolita”

Francesca Capossela puts “The Real Lolita” by Sarah Weinman in dialogue with “Lolita” by Vladimir Nabokov.

By Francesca CaposselaSeptember 12, 2018

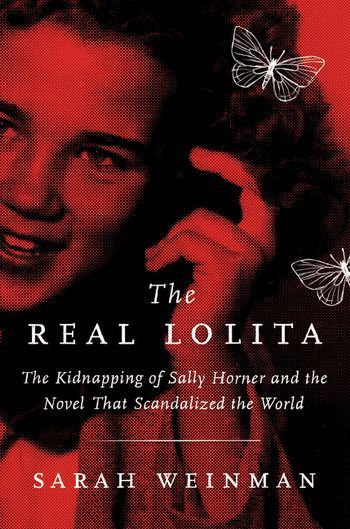

The Real Lolita by Sarah Weinman. Ecco. 320 pages.

IS NABOKOV’S Lolita, a novel narrated by a child molester, still worth reading? With today’s focus on amplifying the voices of the victims of sexual assault, this old question looms with even greater urgency. The novel is especially unsettling in the current climate because it so successfully blurs the lines between fiction and reality, abuser and abused, and narrator and reader. Even Alfred Appel, a staunch defender of Nabokov, agrees that Humbert Humbert turns the reader into an “accomplice in both statutory rape and murder.”

The problem of the narrator is at the heart of Sarah Weinman’s new book. Part true crime, part literary analysis, The Real Lolita recounts the story of 11-year-old Sally Horner, who was kidnapped from a quiet Camden, New Jersey, neighborhood and taken on a cross-country road trip that Weinman believes inspired Nabokov’s novel. The girl’s disappearance in 1948 and untimely death in 1952 aroused the kind of morbid public fascination that is reserved for missing (white) girls. By telling Sally’s story, and emphasizing the Lolita connection, Weinman attempts to pull back the veneer of Humbert’s narration and present the victim’s point of view.

The true violence of Lolita, and the motivation for Weinman’s book, is not Humbert’s sexual abuse, but his stripping Lolita of her voice: the very act of narration. “Real little girls,” Weinman writes, “end up getting lost in the need for artistic license. The abuse that Sally Horner […] endured should not be subsumed by dazzling prose.” Weinman considers Nabokov’s appropriation of Horner’s story likewise violent (though she apparently sees no irony in her own appropriation of Horner's tale). The facts, Weinman believes, will resurrect, or at least avenge, these girls.

We follow Horner across the United States: from her small Camden home, to the dingy Baltimore apartment where she lived with Frank La Salle, to the San Jose trailer park in which she found the courage (and telephone) to call home. Seventy years later, Weinman wanders the same streets, searching for insight into Sally’s story. She and her reader pore over photographs, analyzing the emotion in Horner’s eyes and the color of her lipstick.

Despite Weinman’s proclivity for the factual, The Real Lolita has to make do with a lot of unknowns. About Horner’s time in Baltimore, Weinman writes, “If there are people still living who knew her at the time, I could not track them down. If she kept a journal during her captivity, it did not survive.” She goes on to say that “[i]magination will have to fill in the rest.” Abuse, by nature, silences. Sally’s family rarely, if ever, spoke of her trauma, and we cannot return to Sally’s story in the same way we can return to Lolita’s.

As the book progresses, Weinman becomes increasingly determined to prove unequivocally that Lolita is based on Horner’s life. If Lolita is Sally, then The Real Lolita would be a counter-narrative to Humbert’s: a story focused on the victim, not the rapist. And Weinman is, to some extent, correct. Lolita includes an irrefutable reference to Sally Horner’s kidnapping. But there is no epiphany in Weinman’s book in which the fictional and factual align to reveal some real Lolita.

By the end of The Real Lolita, I could not help feeling tenderness for Horner. Weinman has presented a compelling outline of a life — touching in its pain, resilience, and surprising banality, and animated by the author’s impressive ability to tell a good story even when the material is slim — but she hasn’t managed to fill it in. The questions of victimhood gnaw at us long after the “real” story has been told. What is it like to suffer? What is it like to survive? How does a little girl cope with the absurdity of life, and with her own unarticulated pain? How does she wrest back control?

Ironically, if we want to hear a victim’s voice, we have to return to the fictional Lolita.

¤

Though she is only quoted saying roughly 2,000 words in a novel of 112,473, Lolita miraculously manages both to express her own narrative and to subvert Humbert’s. She studies dialogue, mispronounces words to convey alternate meanings, parodies Humbert’s nervous tics, mocks his pretentions, and speaks metafictionally (“you talk like a book, Dad”). She annotates roadmaps with lipstick, transforms the tennis court into a magical canvas, and matures from a helpless passenger into a fully capable driver, who sits “ludicrously at the wheel.” These verbal habits, varied interests, and physical abilities are given short shrift by critics as simply signs of her adolescence, as if she were a real little girl and not the focal point of a complex literary ballet. There is an anxiety about analyzing Lolita, as if due to past trauma she should be spared from literary criticism. But she is literary, perhaps the most literary character in Lolita, and, when carefully read, she sits at the steering wheel of the novel.

Leading Humbert to a window display one afternoon, Lolita presents him and the reader with a roadmap for reading her book:

[T]wo figures that looked as if some blast had just worked havoc with them. One figure was stark naked, wigless and armless […] when clothed it had represented […] a girl-child of Lolita’s size […] Next to it stood a much taller veiled bride, quite perfect and intacta except for the lack of one arm. On the floor […] where [a] man crawled about laboriously with his cleaner, there lay a cluster of three slender arms […] Two of the arms happened to be twisted and seemed to suggest a clasping gesture of horror and supplication.

Lolita, as if with a “gesture of horror and supplication,” guides us to the mutilated young female body “stark naked, wigless […] armless […] sexless.” Her mother is a “veiled bride.” Humbert crawls around on the floor, attempting to make the show window beautiful, to aestheticize the traumatic image.

Lolita traces a story, like all writers must, through image and language. “The word is incest,” she tells Humbert. Twice she says: “you raped me.” Her voice is buried beneath Humbert’s lusciously articulate narrative — “obfuscation” is the word Weinman uses to describe Humbert as well as Vladimir and Véra Nabokov — but it is nonetheless present. Indeed, the obfuscation, rejection, and perversion of reality are the very subject matter of Lolita; it is a book about fiction itself.

In a lecture on Dickens, Nabokov described fiction as “a magic democracy where even some very minor character […] has the right to live and breed.” The world of Lolita is one of powerful equality, in which Lolita becomes an essential, though obscured, force. While the novel does silence, both through rape and through narration, the persistence of its titular character demonstrates how, in fiction, even the voiceless can be heard.

The cover of The Real Lolita is a photograph of Sally Horner, eyes glittering, as she speaks to her family after her rescue. We can imagine her, hurt and frightened, taking some small pleasure in posing for the cameras. Lolita and The Real Lolita are both confrontations with the silence of abuse, the tyranny of the male narrator, but they are also, at their cores, celebrations of two girls whose lives and deaths are simultaneously tragic and banal, heroic and endearing, terrible and human.

And yet, ultimately, only the fictional girl succeeds in undermining the male narrator. Lolita retains power; Sally cannot. That is the magical democracy of fiction. Only the fictional Lolita can appear to us, vibrant and resilient. If Sarah Weinman wants to hear the silenced speak, she might turn to the only realm in which that is possible — the realm of art.

¤

LARB Contributor

Francesca Capossela is currently pursuing a master's of Philosophy in Creative Writing at Trinity College Dublin. Her writing has appeared in Hanging Loose Magazine, The Point Magazine, and VICE.com. She is working on her first novel.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Surreal Sources of “Lolita”: Nabokov and Dalí

Delia Ungureanu uncovers the hidden surrealist subtext of Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita.”

Was “Lolita” About Race?: Vladimir Nabokov on Race in the United States

Jennifer Wilson measures the social conscience of Vladimir Nabokov.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!