These Creatures: On Cosey Fanni Tutti’s “Re-Sisters”

Arielle Gordon reviews Cosey Fanni Tutti’s “Re-Sisters: The Lives and Recordings of Delia Derbyshire, Margery Kempe & Cosey Fanni Tutti.”

By Arielle GordonFebruary 20, 2023

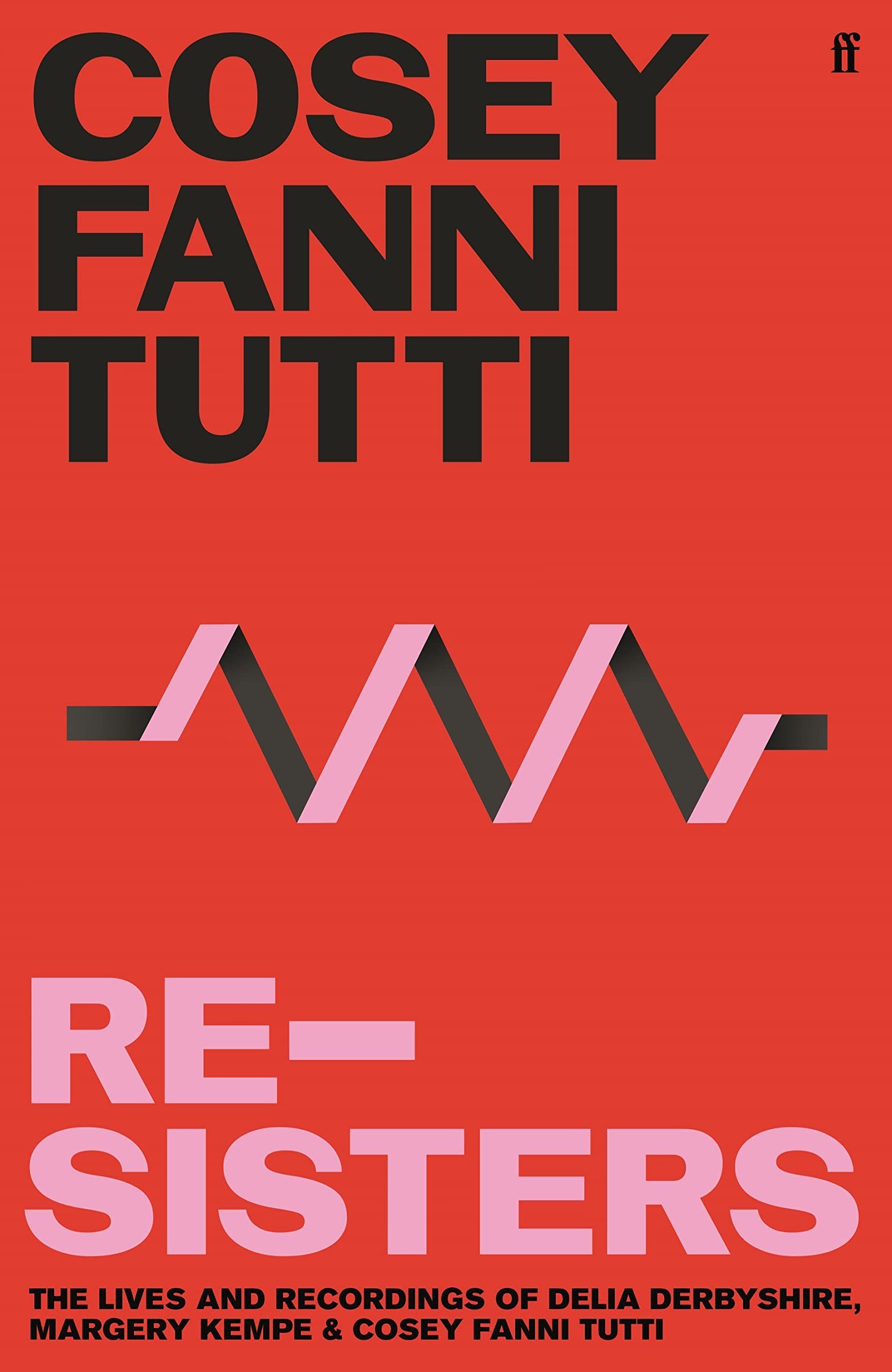

Re-Sisters: The Lives and Recordings of Delia Derbyshire, Margery Kempe & Cosey Fanni Tutti by Cosey Fanni Tutti. Faber & Faber. 304 pages.

BIOGRAPHY, LIKE DOCUMENTARY, is necessarily an intervention in the lives of the writer’s chosen subject. The editorial process — which events to include, which contemporaries to interview — orders history according to the author’s own perspective and dramatic sensibilities. The pioneering performance artist and musician Cosey Fanni Tutti is doubtlessly familiar with the mythologizing work of historicization, having published her first book, the detailed if dry autobiographical memoir Art Sex Music, in 2017. Her follow-up, Re-Sisters: The Lives and Recordings of Delia Derbyshire, Margery Kempe & Cosey Fanni Tutti, makes even more manifest this process of self-insertion through a winding, loosely structured narrative that is neither entirely a memoir nor purely a historical survey. Instead, Tutti takes us through her research of Derbyshire and Kempe, weaving her own commentary and day-to-day life throughout. Like her conceptual artworks — reclaiming her nude modeling as “magazine actions,” which worked to center the woman in the photo rather than the leering — Tutti’s latest book takes a process-centered and inherently feminist approach to biography, highlighting the ways gender both shaped and impeded her subjects’ lives. The act of being immersed in the lives of two notable women from Britain’s history, she argues, is a literary end in itself.

About five years ago, Tutti was fresh off the book tour for Art Sex Magic and had seen the completion of a well-regarded museum retrospective of her performing art troupe COUM when she learned that her memoir was going to be adapted into a movie, funded by the British Film Institute. After decades of being derided by polite British society for her controversial performances — and overshadowed in her own group, Throbbing Gristle, by abusive bandmates — Tutti was, in her mid-sixties, finally experiencing the level of recognition that she and others felt she had long deserved.

During Tutti’s tour, the actor and director Caroline Catz approached her about participating in an unconventional biopic about the life of Delia Derbyshire, the trailblazing British electronic musician best known for producing (or “realizing”) the original theme song to Doctor Who. Catz asked if Tutti would be interested in composing a soundtrack for the film, in addition to possibly acting in it. In accepting Catz’s offer, Tutti found herself cocooned in a narrative nesting doll, seeing herself represented in one film while reflecting the life of another undersung woman in Britain’s cultural history.

As if the challenges of the Art Sex Music film and Catz’s biopic were not sufficient for her own self-discovery through memoir, Tutti became simultaneously fascinated with another revolutionary woman. While browsing a secondhand shop in King’s Lynn, near her Norfolk home, Tutti discovered a book about the 15th-century Christian mystic Margery Kempe. Originally from King’s Lynn, Kempe is (fittingly) most well known not for her ecstatic visions of God but for her recollection of her own history. Illiterate, she dictated her life’s story to two separate scribes before her passing; the result (The Book of Margery Kempe, c. 1445–50) is what many consider the oldest known autobiography written in English. These three women — Derbyshire, Tutti, and Kempe — are the subjects of Re-Sisters.

Though she provides a bespoke, often humorously contemporary lens through which to view their individual accomplishments, Tutti’s latest book cannot help but feel claustrophobic, even told over 300 pages. Her interest in each woman is obvious — they led fascinating lives indelibly marked by their passions, rebelliousness, and gender. But their stories are flattened by Tutti’s meandering prose and emphasis on direct comparison. In attempting to weave the narratives of her fellow British pioneers with her own, she trivializes their discrete struggles and successes, forcing them into a shallow, facile vision of female resilience.

Re-Sisters recounts Derbyshire’s life in chronological order, from her days as a working-class child in Coventry to her studies at Cambridge and, crucially, her admittance to the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop. The Radiophonic Workshop was in essence the special effects arm of the BBC; its mandate was to produce “sounds from natural or artificial sources to convey the mood of a broadcasting programme, but not the creation of musical compositions as such.” It was as a studio trainee there that Derbyshire first learned about tape manipulation, a novel technology that allowed Radiophonic Workshop engineers to alter the frequency and pitch of prerecorded sounds. Played simultaneously, these milliseconds of recordings created unheard, inhuman compositions.

A mathematician as well as a musician, Derbyshire immediately took to the painstaking process of splicing tape segments and rearranging them, working late hours at BBC’s Maida Vale Studios to run meters of surgically altered tape throughout the building. She was an avid drinker, and one popular legend notes that she used partially drunk bottles of wine and cider, of varying volumes, to create a variety of sounds for her work. Despite producing some of the most iconic sounds of that era of BBC televised programming, she and other engineers were never individually credited; they weren’t considered “composers” of the pieces, just compilers. By the end of the 1960s, the BBC had made most of the workshop redundant, the invention of synthesizers allowing them to produce more sounds faster and with fewer employees. Derbyshire fell further into alcoholism and isolation, frustrated by the direction electronic music had taken — and her inability to meet its new demands.

Margery Kempe’s narrative begins, as with so many women in literature, after the birth of her first child. Driven by what scholars now assume was postpartum psychosis, she had visions of Jesus Christ and began a life of asceticism. She wore hair shirts, prayed for chastity, wept continuously. Her mission became to devote her life to serving as the wife of Christ, making treacherous pilgrimages to Jerusalem, Spain, and Prussia. In her book, she (awesomely) refers to herself as “this creature” to show her deference before God. Some, like the anchoress Julian of Norwich, believed her devotion to be genuine; most seemed to find her almost unbearably annoying.

The project of connecting three women across six centuries is ambitious. Yet, despite Tutti’s depth of knowledge and compassion for her subjects, her attempt to draw comparisons between Derbyshire, Kempe, and herself often disserves all three. The commonalities between Kempe and Derbyshire, aside from Tutti’s interest in them, are hazy at best. She notes that she came across a book with the author “Kempe” while researching Derbyshire — how kismet! — and that both women navigated patriarchal systems to succeed. At its most difficult, her direct juxtaposition trivializes their narratives. One particularly flagrant chapter finds Tutti comparing the physical exertion required for Kempe’s medieval pilgrimage to the exhaustion she feels at the end of a tour.

In constantly seeking direct parallels between her own life and those of Kempe and Derbyshire, she reduces the experiences, setbacks, and accomplishments of her subjects to their relatability. She often contorts the stories of her “sisters” into preambles for self-aggrandizing anecdotes. Tutti also struggles to balance their narratives with her commentary on writing the book itself, and the pacing suffers as a result: some chapters are devoted entirely to a dry recounting of Kempe’s trials for Lollardy, while others are extemporaneous ramblings on whatever comes to Tutti’s mind — HBO’s Chernobyl (2019), sexual intimacy, writing shorthand — loosely connected to one, two, or three of the women at hand:

It crossed my mind that Delia would have benefited from learning shorthand and probably would have liked it. My sister was taught it and could do over 120 words per minute. It fascinated me to watch her making abstract squiggles. It’s like a secret code. I’m not sure I could have mastered the skill. Too much to ask of me to keep those abstract shapes within the constraints of their meaning. I’d have started forming patterns of my own from them, riding roughshod over the rules and creating nonsensical words … which isn’t such a bad idea. I love the look of words whatever the language and style, especially the beautiful medieval script in Margery’s book.

Still, while Tutti fails to synthesize the lives of these three women, she does empathize with their separate trials. Their overlapping stories do sum to a larger narrative about creative women: Kempe and Derbyshire were both anchoresses of a sort, eschewing opportunities for social connection in favor of a monastic dedication to their driving passions. Both were discontents of their time: Kempe, in her endless devotion to Christ, and Derbyshire, unwilling to move beyond her beloved musique concrète methods and adapt to synthesizers. Separately, American readers might be struck, as I was, by the state funding provided for arts in Derbyshire and Tutti’s careers, the former directly through her employment at the BBC and the latter through a series of Arts Council grants.

Re-Sisters also benefits from Tutti’s fearlessness in addressing abuse. In Art Sex Magic, she recounts the horrific physical and mental torment she suffered at the hands of Genesis P-Orridge, her longtime collaborator in Throbbing Gristle and COUM Transmissions. Here, she directs her ire towards Peter Kember, a later collaborator of Derbyshire’s. A former member of Spacemen 3, Kember is usually spoken of as a beloved partner in Derbyshire’s later work; according to Martin Guy’s compendium of information on Derbyshire, WikiDelia, the two were so close that Derbyshire gifted him her beloved VCS3 synthesizer. But Tutti tells a different, heretofore unheard story:

There had been talk with Peter of setting up a Delia Derbyshire website. Then, apparently to her utter surprise, it appeared, launched without her consultation or permission. She was furious. She felt ‘used’ — that her name and her life had been borrowed by other people to make them look good.

Delia wanted to end the collaboration with Peter and asked him for her equipment back. […] Peter refused to return it. […] Peter’s understanding was that Delia had gifted it to him. […]

As sole beneficiary of Delia’s estate Clive [Blackburn, her nonromantic life partner] approached Peter Kember, as did Mark Ayres, both requesting that he return Delia’s equipment so that it could be placed within her archive. Frustratingly they met with refusal, for the same reason given to Delia when she’d asked. Delia’s VCS3 was sold, and as far as I’m aware no one knows where it ended up.

Insights like these give meaning to the otherwise dense and convoluted memoir — in Tutti’s research, at last, Derbyshire’s side of the story is revealed. Unfortunately, Tutti mostly prefers to chew the fat of her narratives, rather than excavating their muscular core.

When we consider that Tutti has already contributed to Derbyshire’s story through her soundtrack, it prompts an existential question about the project of Re-Sisters. Tutti’s music for the Derbyshire biopic, in contrast to her book, is sharply rendered, subtle but gripping in its embodiment of Derbyshire’s life and creative process. At the same time, Kempe’s story has recently been recontextualized by a number of prominent writers: Victoria MacKenzie’s For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain (2023) is an engrossing fictional account of Kempe and Julian of Norwich’s lives; cultural historian Janina Ramirez’s Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It (2023) revisits Kempe, alongside other medieval women, telling the stories of women who were largely erased from history by its male authors. Re-Sisters, then, is more of a diaristic collage to serve Tutti’s own self-narrative, a project of autobiography disguised as several biographies. Tutti takes on a Sisyphean task in Re-Sisters, especially when the narratives of both Kempe and Derbyshire are better served by other mediums and by more reliable narrators.

¤

LARB Contributor

Arielle Gordon is a writer based in Brooklyn. Her work has been featured in Pitchfork, The Ringer, The New York Times, and Stereogum, among other publications.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Not Just a Daughter: On Stephanie LaCava’s Short Film “Based On, If Any”

Sarah Fensom reviews Stephanie LaCava’s “Based On, If Any.”

Love Labor: On Touring as an Independent Musician

Eli Winter details the material and psychological quirks of touring as an independent musician.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!