A Way of Taking in the World

Sven Birkerts on Teju Cole's new essay collection, "Known and Strange Things."

By Sven BirkertsOctober 23, 2016

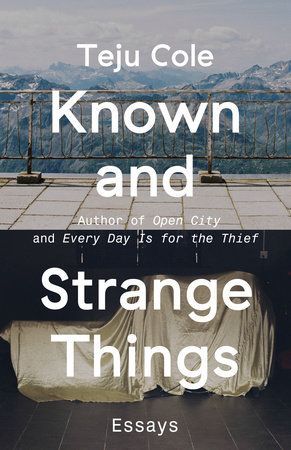

Known and Strange Things by Teju Cole. Random House. 416 pages.

“I USED TO WONDER what creative freedom would look like,” writes Teju Cole in the preface to Known and Strange Things, his first collection of essays. “If I could write about anything I wanted, what would I write about? It has been my immense good fortune to have exactly that opportunity.” The great success of his 2012 novel Open City, coupled with his impressive range of cultural interests, put this young, US-born Nigerian writer in the way of the kinds of carte-blanche magazine assignments — for The Atlantic, the Guardian, and The New York Times Magazine — that most of us can only dream about. If that were not enough, Cole’s self-effacing and fluent presentation style has made the whole business look both inevitable and easy.

Of course it’s nothing of the kind. Real achievement is always earned. Here too. But my sense is that the hard work for Cole might have been more that of self-making — of the stage-by-stage evolving of his original sensibility — than of struggling to get the words onto the page (I may be wrong here). He has an angle, a stance, a voice. If I were the assigning editor at one of these celebrated venues, I know I would be interested. I would hire the man for his obvious gift of writerly instinct, to see just what he might come up with.

Following that instinct, Cole has written a great many essays on a range of topics — many more than are included in the book. He has selected from these toward some imagined unity — even as he allows in his preface that there could be any number of other unities possible. For this gathering, he admits, he has favored his pieces on photography (he writes a regular photography column for The New York Times Magazine), but he has also included a good number of literary reviews and reminiscences, as well as a sampling of political reflections and travelogues. It makes for a nice variety. Alongside more specific engagements, Cole offers a personal account bouncing off James Baldwin’s well-known essay about being the one black man in a Swiss village; narrates a meeting with the irascible bigot V. S. Naipaul; unpacks an afternoon spent with a garrulous cabbie as he sets forth to find the grave of W. G. Sebald. Known and Strange Things, whether fortuitously or by design, gives us the parts and assembly instructions for a distinctive aesthetic outlook, even as it enlarges the artistic canon to a wider circumference.

Cole brings us his discoveries and celebrations of the often lesser-known artists he has come upon in his wanderings. An outsider and a flâneur, he is a man of many interests and several strong compulsions — and he makes his way forward by following the flights of his restless sensibility.

One way to get at this sensibility — I don’t know that there is any best way — is by looking at the essay “Always Returning,” his anecdotal and deceptively casual recounting of that visit to Sebald’s grave. In just a few pages, we see Cole’s essayistic method and get some hint of his deeper preoccupations.

We know from his preceding essay, aptly titled “Poetry of the Disregarded,” that Cole owes a profound debt to the German exile, a debt less stylistic than temperamental. Sebald moved his melancholic prose sinuously from association to association. He caught the feeling of the world as experienced by the displaced, those cut off from their pasts. He also demonstrated an almost preternatural ability to get things — seen things — to disclose. Writes Cole: “he understood especially well the private life of objects. As he wrote […]: ‘Things outlast us, they know more about us than we know about them.’” Reading the essays, we see that Cole is very much a writer in Sebald’s lineage.

“Always Returning” moves along with a deceptively casual momentum. “One morning this past June, I played truant from a conference I was attending […]” the writer sets off in a cab and gives him a destination — St. Andrew’s Church — without disclosing his objective to the driver or to us. As they drive, the cabbie shows himself to be something of a local historian and begins pointing out various significant sites. The area was once thick with airfields, he explains, and during World War II the British sent out thousands of bombing raids. Listening, Cole suddenly feels carsick and asks his driver to stop; he has to get something to eat. In fact, his nausea is accompanied by a simultaneous memory jolt. “And at that moment, with a flickering photographic recall, as though someone had just switched on a slide projector, I remembered something W. G. Sebald had written.” He then reproduces the passage, with its horrifying statistics — how “the eighth air fleet alone used a billion gallons of fuel, dropped seven hundred and thirty-two thousand tons of bombs, and lost almost nine thousand aircraft and fifty thousand men” — and we see just what he means. Such a convergence of moment and memory, yet when Cole later tells the driver where he is going, whose grave it is he wants to see, there is no recognition. Two men of kindred obsession, living so near to each other — but no connection.

After looking at the grave, Cole quotes again from Sebald, this time from The Rings of Saturn — two sentences which go to the core of his own view of things, not to mention the slyly encoded point of the essay:

Across what distances in time do the elective affinities and correspondences connect? How is it that one perceives oneself in another human being, or, if not oneself, then one’s own precursor?

If this were a work of fiction, and if we were mapping it to Freytag’s well-known “pyramid,” with its rising action, climax, and denouement, the quote would be the apex of the figure. The denouement — the tying up of threads — comprises the last two paragraphs. Back at the conference, Cole first wanders around the campus of the university, noticing as he does that a large magpie seems to be following him around. When he gets back inside, a colleague tells him, seemingly out of the blue, that Sebald had been known to wear two watches, one on each wrist, and that no one ever knew to what purpose or how they were set. A deep association is struck: Cole thinks of the magpie, with “its eye for the sudden shards of brightness that enliven the ordinary.” When he steps outside later, it’s nearly dark, but there is the bird again, “going from bush to bush in the uphill path ahead of me, little more than a shadow now.”

The account requires no unpacking. Its method is suggestion, implication. What I would pause over, though, and take for my uses here, is the magpie itself, which seems to me the herald, the totem, of Cole’s aesthetic.

This alert scavenging instinct is deployed across Cole’s wide spectrum of interests and it results, as noted, in an excitingly heterogeneous mix of topics. In his literary reflections he goes from James Baldwin and W. G. Sebald to Tomas Tranströmer, Derek Walcott, and André Aciman, but also includes South African novelist Ivan Vladislavić and Sri Lankan memoirist Sonali Deraniyagala. An independent catholicity of taste is obvious. His considerations of artists and photographers project that same impulse — that set of predilections — onto the visual and performative realm. Essays on Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu, director Gregory Doran’s production of an African Julius Caesar, and Tasmanian composer Peter Sculthorpe nudge us off the more well-traveled paths. They make a case for reassessing the canon, not by argument but by example — by enlarging the field of consideration. This, I kept thinking, is how a truly cosmopolitan individual greets the world.

But as Cole noted in his preface, the main preoccupation in these pages is photography, and if the literary pieces and travelogues are quick with observed detail, the photo pieces carry a fellow-practitioner’s particular passion. As it happens, I’d recently been reading Geoff Dyer’s book about photography, The Ongoing Moment, in which Dyer, though not unlike Cole in his wayfaring temperament, announces right off that he does not himself take pictures, that he instead works as a passionate outsider. The comparison is revealing. Dyer’s sideline vantage encourages a thematic approach. He does a superb job of tracking subject obsessions and stylistic signatures from one photographer to the next, but the reflective distance is everywhere felt. Cole’s insider’s passion, by contrast, is apparent throughout these essays.

Here he is, for example, writing about Saul Leiter:

One of the most effective gestures in Leiter’s work is to have great fields of undifferentiated dark or light, an overhanging canopy, say, or a snowdrift, interrupted by gashes of color. He returned again and again to a small constellation of subjects: mirrors and glass, shadows and silhouettes, reflection, blur, fog, rain, snow, doors, buses, cars, fedoras. He was a virtuoso of shallow depth of field: certain sections of some of the photographs look as if they have been applied with a quick brush.

This is a specifically informed characterization. We see that Cole is thinking as one who has himself wrestled with light, color, and mass, but without getting lost in shoptalk or craftsplaining. He is soliciting our interest at the same time as he is illuminating a particular way of taking in the world.

Similar informed focus animates Cole’s essay on African-American master Roy DeCarava, in which he foregrounds the technical (but also implication-rich) problems once involved with photographing black skin. “The dynamic range of film emulsions […] was generally calibrated for white skin and had limited sensitivity to brown, red, or yellow skin tones. Light meters had similar limitations, with a tendency to underexpose dark skin.” It’s hard not to read that first sentence as a capsule history of American imperialism, though Cole’s touch is light.

Exploring DeCarava’s work with black subjects, Cole moves deftly between a more descriptive characterization and a pointed remarking of the racially charged contexts within which his photos were presented:

These images pose a challenge to another bias in mainstream culture: that to make something darker is to make it more dubious. There have been instances when a black face was darkened on the cover of a magazine or in a political ad to cast a literal pall of suspicion over it, just as there have been times when a black face was lightened after a photo shoot with the apparent goal of making it more appealing.

The essay, entitled “A True Picture of Black Skin,” concludes on a more overtly ominous note:

These pictures make a case for how indirect images guarantee our sense of the human. It is as if the world, in its careless way, had been saying, “You people are simply too dark,” and these artists, intent on obliterating this absurd way of thinking, had quietly responded, “But you have no idea how dark we yet may be, nor what that darkness may contain.”

The adjective “quietly” is the most loaded word in the passage.

The collection does have blackness as one of its several dominant themes. From the opening essay, “Black Body,” in which he plays his experiences as a black man in Switzerland against his reading of Baldwin’s famous essay — how much has changed, and how much is just the same — to his piece on the night of Obama’s first presidential win, when he recounts slipping into bed late only to hear his wife murmur, “Welcome home, Mr. President,” Cole surveys and suffers the racial landscape from his own complex vantage. As is so often the case, it is the outsider’s eye that throws familiar assumptions and behaviors into high relief.

Engaged expertise informs the other photo essays to other ends. From DeCarava’s treatment of blackness, Cole moves to a series of reflections on picture-taking (and, by implication, other arts) in our era of visual saturation. The writer who lingers over the composition of a single image, breaking out its most covert suggestions, can also contemplate the various impacts of the digital on our processing of images. “Nearly one trillion photographs are taken each year,” he writes in “Finders Keepers,” “of everything at which a camera might be pointed.” And a few sentences on, he adds: “The flood of images has increased our access to wonders and at the same time lessened our sense of wonder. We live in inescapable surfeit.”

A number of artists, he notes, are responding to this glut by gathering and arranging images found on the internet — juxtaposing, cropping, subjecting them to various treatments — raising all sorts of questions about originality, ownership, and appropriation. “What are the rights of the original photographers,” Cole wants to know, “the ‘non-artists’ whose works have been so unceremoniously reconfigured?” And what is their status?

After all, images made of found images are images, too. They join the never-ending cataract of images, what Whitman called the “immense Phantom concourse,” and they are vulnerable, as all images are, to the dual threats of banality and oblivion — until someone shows up, says “Finders keepers,” rethinks them, and, by that rethinking, brings them back to life.

He goes on in another essay, “Google’s Macchia,” to ponder the implications of the algorithm that supports Google Image Search. We now have a way of reading the very smallest pictorial elements as information, finding patterns of likeness among the most outwardly disparate images. Cole is fascinated — he submits his own images to such comparison to learn what he can about their deeper structure — but he senses, too, how this represents a further erosion of subjectivity, and, indeed, the workings of chance that he celebrates in such a variety of forms. The deeper the incursion of data, the more threatened the age-old premises of art, and, perhaps, the more precious are its special insights.

The Sunday magazine think piece, which is the origin of many of Cole’s photography essays, is the ideal vehicle for a targeted in-and-out “take” on a single artist or issue — like the portrayal of black skin, or broad effects of iPhone image manipulation, or the history of aerial photography and the use of drones in image-making — but topic limits and length requirements can begin to impose a certain uniformity. Happily, Cole does not confine himself to high-end journalism. In a number of his longer pieces, he shows himself to be a superb personal essayist. He knows how to control anecdote and digression, create suspense, and hold everything together with the spell of a natural, even confiding, voice.

One such essay is “Far Away from Here,” which is, on the surface, an engaging chronicle of a period Cole spent at an arts institution in Switzerland where he let himself get caught up by the challenge of photographing the extraordinary alpine beauty. Within a few paragraphs — from the moment of his arrival — we know just how serious he is:

What I wanted was an SLR film camera. Sure, there was the cluttered cabinet in my New York City apartment with its eight cameras and their various lenses and filters: the Hasselblad, the Nikon, the Leica, a couple of other Canons, some cameras I hadn’t touched for years.

I look wistfully at my iPhone: I’m all ears.

Soon enough, Cole pulls us in with the specific atmospherics. He is on the Gemmipass, he writes, “2,770 meters above sea level and 670 meters above the town of Leukerbad […] I’m hunched over the tripod, pressing the shutter every few seconds. The weather has suddenly turned. Is this rain? Fog? I wipe the lens clean. Not only am I the only black man on the pass just now, I am the only human being of any kind.” The “only black man” observation refers, we now know, to the Baldwin essay, when that writer spent a long-ago winter in Leukerbad and wrote, “From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came.”

But Cole quickly steps back to supply context: the Alps in history and then the Alps as seen by artists and photographers through the ages. He is sketching in a lineage that he himself hopes to join, however modestly. After setting up this much-traversed terrain, he observes: “The question I confronted in Switzerland is similar to that confronted by any camera-toting visitor in a great landscape. Can my photograph convey an experience that others have already captured so well?” Cole has already to some degree alerted us to his own aesthetic bias, the basis of his procedure. He is the opportunist of the telling detail. Now, reflecting on the hyper-thorough description in the old Baedeker guides (for decades the universal travelers’ Bible), he reflects: “What is […] interesting to find […] [are] the less obvious differences of texture: the signs, the markings, the assemblages, the things hiding in plain sight in each cityscape or landscape.” He is after the subtle signature, the suggestive nuance that has not yet been captured.

Cole recounts his search for the subject and rendering that would be his own. There are many outings, many failures. The whole process puts him in the way of great beauty, but “ambition always comes to darken your serenity. Technically proficient mountain pictures were good, but I also had to develop my own voice. In photography, as in writing, there’s no shortcut to finding that voice.” As readers, we feel caught up in Cole’s self-imposed mission. “I became less interested in populating my images and more interested in traces of the human without human presence.” And: “I felt the constant company of doubt: my lack of talent, my impostor’s syndrome, my fear of boring others.”

After this, Cole embarks on a riff about homesickness, what the Germans call heimweh, as experienced by 15th-century Swiss mercenaries. This builds to become a quiet sub-theme, this longing, one he develops further by invoking Elizabeth Bishop, her great poem “Questions of Travel”: “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?” the poet asks. Cole answers in his way, identifying as he does the paradoxes of his unhousedness: “I was most at home in Switzerland precisely because I wasn’t. It made me happy because it couldn’t.”

It is at this point that “Far Away from Here” shifts from being an observational chronicle and takes on some of the specific gravity of an essay. His two central themes, clearly aspects of his writerly compulsion, are now allowed to overlap: that of expression — the author’s ambition to find his “voice,” to photograph the landscape in ways that are uniquely his — and that of home. The two are, of course, not unrelated. As Cole writes, “The term ‘at home’ describes both a location and a state of being.” His traveler’s isolation, which is at times also an alienation, brings the ambition and the longing into tension.

The story is not quite finished. Returning to New York, studying the photos from the 80 some rolls of film he has developed, Cole feels that he has almost enough for a book. Almost, not quite. Something is still missing — he knows he needs to go back. The essay’s last short passage finds him back in Zurich eight months later to finish his undertaking.

Cole has, he tells us, been out taking pictures all day but has nothing he likes. Charged up and frustrated, he gets an idea. He sets up his Canon on a tripod right there in his hotel room. Pivoting the camera, he takes in a large picture of a ship on a lake which covers the front of the wardrobe. The vista has haunted him: “You could wake up suddenly at night in this room and, seeing that lake dimly lit by a streetlight, imagine yourself afloat: the slightly vertiginous thrill of being nobody, poised in perfect balance with the satisfaction of having, for that moment, a room of your own.”

We feel with Cole both the wanderer’s alienation and the powerful call of home. “I face the wardrobe,” he tells us,

I open the windows behind me and increase the camera’s exposure setting slightly. A black lamp, gray striped wallpaper, the wardrobe, a foldable luggage rack […] Arrayed like that they look like an illustration in a child’s encyclopedia. This is a door. This is a ship. This is a lake. […] This is a man in a room, crouched behind the camera, readying his shot, far away from home, not completely happy, but happier perhaps than he would be elsewhere.

His is the most elusive and indeterminate sensation, but describing it gives him the note he needs to close the essay, to bring art and consciousness into a vibrant suspension. This, we guess, will be the photo that completes the book he is making, that puts the period to all the other images he has gathered, of crags and ridges and massive folds of land. This will be the one that declares their reason for being.

Significantly, Cole also includes this photo in one of the book’s two insert sections. The image is stunning. But since I came upon it after reading this essay, I can’t view it apart from the narrative context. I have to question myself. Would I find in it that same perfect blend of longing and clarity if I did not have an imagining of a man away from his home, alone, a stranger in a city? After reading this book of essays, I want to say yes, that it is exactly the point of the artist’s work — indeed, that if we knew the story behind everything there would be no need for art.

¤

Sven Birkerts most recently authored Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age.

LARB Contributor

Sven Birkerts co-edits the journal AGNI at Boston University and directs the Bennington Writing Seminars. His most recent book is Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age (Graywolf).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Explaining Ourselves to Ourselves

Patrick Madden explains himself to Micah McCrary.

Cocks and Flowers

What do we see when we look at Robert Mapplethorpe's flowers?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!