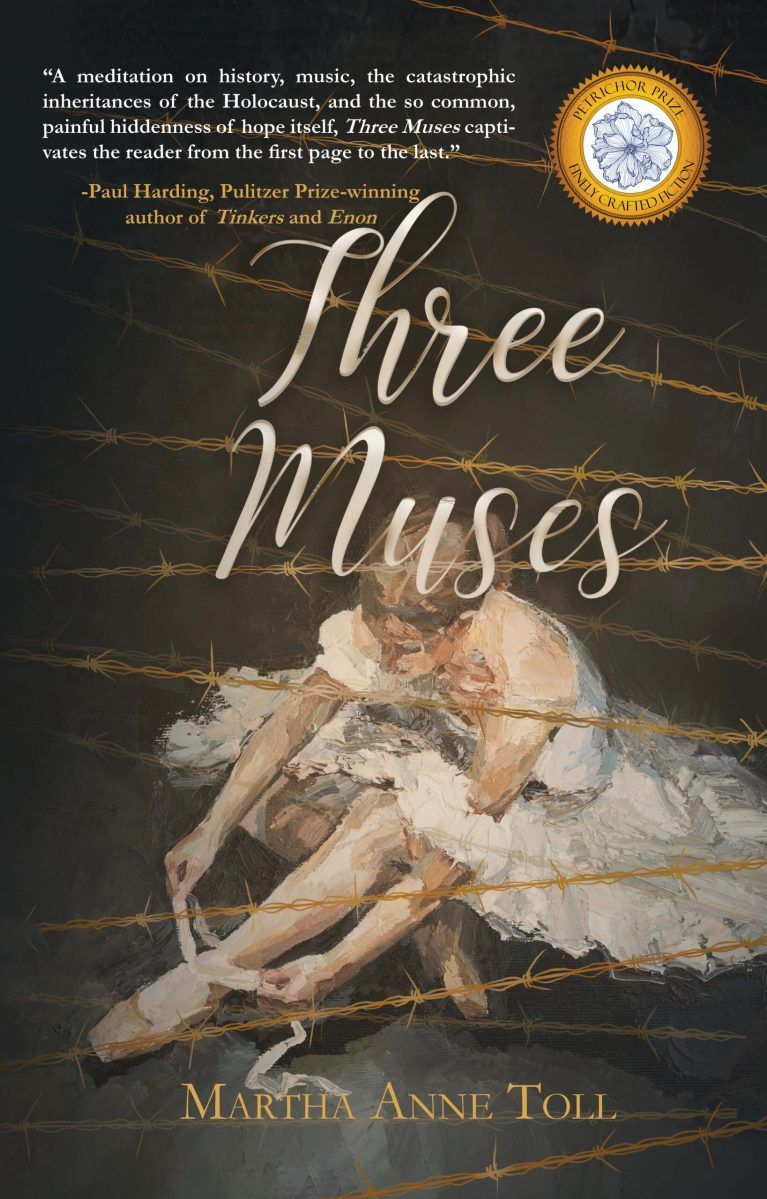

A Singular Disappointment: On Martha Anne Toll’s “Three Muses”

Debby Waldman is not inspired by Martha Anne Toll’s “Three Muses.”

By Debby WaldmanDecember 21, 2022

Three Muses by Martha Anne Toll. Regal House Publishing. 256 pages.

THE PULITZER Prize winners, National Jewish Book Award winner and finalist, and bestselling authors who offered advance praise for Martha Anne Toll’s debut novel spared no laudatory adjective: beautiful, exquisite, gripping, lyrical, magnetic, phenomenal, powerful — and that’s just a sample. One luminary described Three Muses as “[a] meditation on history, music, the catastrophic inheritances of the Holocaust, and the so common, painful hiddenness of hope itself.”

That’s a lot to live up to, so maybe it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Three Muses falls short. But the truth is, it doesn’t even come close. An unsuccessful mashup of genres (young adult, historical drama, literary fiction, and romance), it’s weighted down by clumsy, clichéd prose, one-dimensional characters, and careless mistakes.

Mind you, it’s not Toll’s fault that the blurbs are so gushy they’re likely to leave readers questioning their judgment or wondering if they’ve been victims of a bait and switch. Maybe the folks who found Three Muses such a satisfying read didn’t make it past the first few pages, which aren’t so bad compared to what follows. Or maybe they just read the plot summary, which certainly sounds promising.

Janko Stein, an 11-year-old boy, survives the Holocaust because his mother makes him sing for the SS at the selection after arriving at an unnamed concentration camp in 1944. His mother and baby brother are sent to the ovens. Janko is escorted by an SS officer to the Kommandant’s house. Renamed Johann, he spends the rest of the war literally singing for his supper (or, more accurately, the occasional fried potato peels cooked up by his minder and whatever scraps he can pull off the plates before they’re washed).

When the camp is liberated in 1945, Johann becomes Janko once again. He heads back to Mainz, where he “pick[s] his way over brick mounds that were bombs’ offspring and struggle[s] to remember where home was,” a struggle that ends a few paragraphs later when he comes upon his childhood apartment building, “a lone tooth in a mouth full of gums.”

As was typical for many survivors who dared return to the places from which they had been removed, Janko quickly learns he’s not welcome. The only thing he takes from his truncated homecoming is a fresh helping of survivor’s guilt, which metastasizes three years later when he arrives in New York City. There, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society finds him new parents, the warm and loving Barney and Selma Katz of Yonkers.

John — his newly chosen name — will conveniently occupy the space that opened up in the Katz’s hearts and home after their son Buddy died fighting in Sicily. John goes to medical school because Buddy was supposed to. And he becomes a psychiatrist because the Katz’s next-door neighbor tells him he should: “You got a heart full of tsuris and a keppe full of nasty memories. It’s scrawled on your forehead like a headline in the New York Post.”

The newspaper comparison also sums up Toll’s prose style, which is about as subtle as a 72-point boldface headline. Yet she does a decent job with structure, unspooling parallel stories of trauma and dysfunction. As Johann toils in the kitchen, polishes boots, and struggles to cling to memories of his idyllic Jewish childhood in prewar Germany, we meet Katherine Sillman, who is four years his junior. Her life is upended at seven years old when her beloved mother is struck down by a car in Queens.

An only child, Katherine can’t count on her father for solace because “Daddy moped around and forgot to give Katherine breakfast and didn’t go to work even though he was an accountant and usually went to work every day including some Saturdays.” She can’t count on her schoolmates because when she “returned to school, everyone avoided her except Mrs. Slattery, who let her be teacher’s pet,” prompting a nasty classmate to hiss, “You’re only getting to hand out papers and wash blackboards because your mom croaked.”

When her father and aunt sign her up for dance classes, ballet becomes Katherine’s salvation and refuge — though given that she starts mooning over Boris Yanakov, the resident choreographer, when she is 11 and he’s close to 40, that’s not such a good thing. Eventually, Boris will become her Svengali. When she’s 17, he gives her a stage name, Katya Symanova, which makes her feel as if he’s given her “a priestly blessing.”

When she’s 21, he beds her after nibbling her ear and holding her chin (“Was that a kiss?” she wonders) and suggesting that she take a bath. A lot of things happen, including this:

He climbed on top of her.

She wanted to scream with pain. And with the bulk of him, thrusting and heaving. And with the occasion, which was momentous. He closed his eyes, his body a force field. It was different and more than what she had imagined — the strength of him, the fervor with which he plunged into her. With a final panting snort, he released himself, his weight crushing her. Is this what people did behind closed doors? It was difficult to breathe.

Spoiler alert: Katya’s relationship with Boris is not the stuff of which dreams are made. John is her soulmate, and she is his. They are destined to find and heal each other. Readers will not fail to make this connection because Toll spells it out. Repeatedly.

For Katya, John “understood — understood everything, it seemed. As if he had known her all her life, yet arrived with the freshness of a budding flower.” He “appeared, like an answer to a prayer.” He “was a flare’s sparkling whoosh. With him she was what she had not been — a spontaneous woman.”

For John, “she was a spirit come by enchantment,” sent to him “by a mysterious fairy godmother.” As he does for her, she frees him to revisit his traumatic past, painful as it is (and it is painful, though not always in the way Toll likely intended). As they lie in bed one morning, John tells Katya about the last time he saw his mother and brother:

“We were hauled away in a truck,” he said, with a sigh. “People died with their eyes open, corpses frozen in sitting position, urine and feces and vomit covering the floor.”

“I can’t do this to you,” he said. “My memories are staining your sheets.”

Making John a psychiatrist means Toll has an ideal canvas on which to examine the interplay of memory, guilt, and trauma, the holy trinity of Holocaust survivor stories. But as with the #MeToo–like relationship between Boris and Katya and the romance between John and Katya, she does little more than skim the surface: we know what’s happening not because she crafts evocative scenes that would give her story some heft and depth, but because she hits us over the head with the literary equivalent of a 100,000-lumen flashlight: We know John is sad because his face is “streaked with tears” or he’s sobbing with his head in his hands. We know he dislikes baring his soul to his training psychiatrist because a “dentist’s drill would be preferable” to those sessions. We know he is tormented because “he would be stuck in an agony of memory forever.”

Three Muses would have been far better had Toll developed characters that a reader could care about. That doesn’t require beautiful writing (though it helps) — it requires an understanding of how to convey human nature and motivation. Contrary to the advance hype, none of that is on display here.

Lavishing praise on a book so undeserving is unfair to readers who expect the unparalleled excellence that the blurb writers of Three Muses described. If you want a story about a survivor who can neither escape from his past nor deal with it, pick up a copy of Ellen Feldman’s truly excellent novel The Boy Who Loved Anne Frank (2005), in which she imagines that Anne’s hiding-place housemate, Peter van Pels, arrives in New York after the war, determined to keep his past to himself, only to be challenged when The Diary of a Young Girl is released to worldwide acclaim. Or check out Stewart O’Nan’s City of Secrets (2016) about a survivor who goes to Israel, where he gets caught up in the Haganah, a Zionist paramilitary group formed in 1920 with the expressed goal of defending the growing Jewish population, in an unsuccessful attempt to forget the past.

If you’re interested in a nonfiction account of the deep-seated trauma experienced by survivors (and their offspring), have a look at Helen Fremont’s stunning memoirs, After Long Silence (2000) and The Escape Artist (2020). All are worth reading.

¤

LARB Contributor

Debby Waldman is an American writer in Edmonton, Alberta. Her work has appeared on a number of sites and in publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, People, and Publishers Weekly.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Desire for a Proper Life: On Cho Nam-joo’s “Saha”

Sheila McClear reviews South Korean author Cho Nam-joo’s new novel “Saha,” translated by Jamie Chang.

Startling Glimmers of Truth: On Ling Ma’s “Bliss Montage”

Kathy Chow reviews Ling Ma’s debut collection of stories, “Bliss Montage.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!