A Poet in Hell

“Salvation Canyon” rises above the survivor-memoir genre and touches on the elemental power of consciousness.

By Jack SkelleyNovember 17, 2020

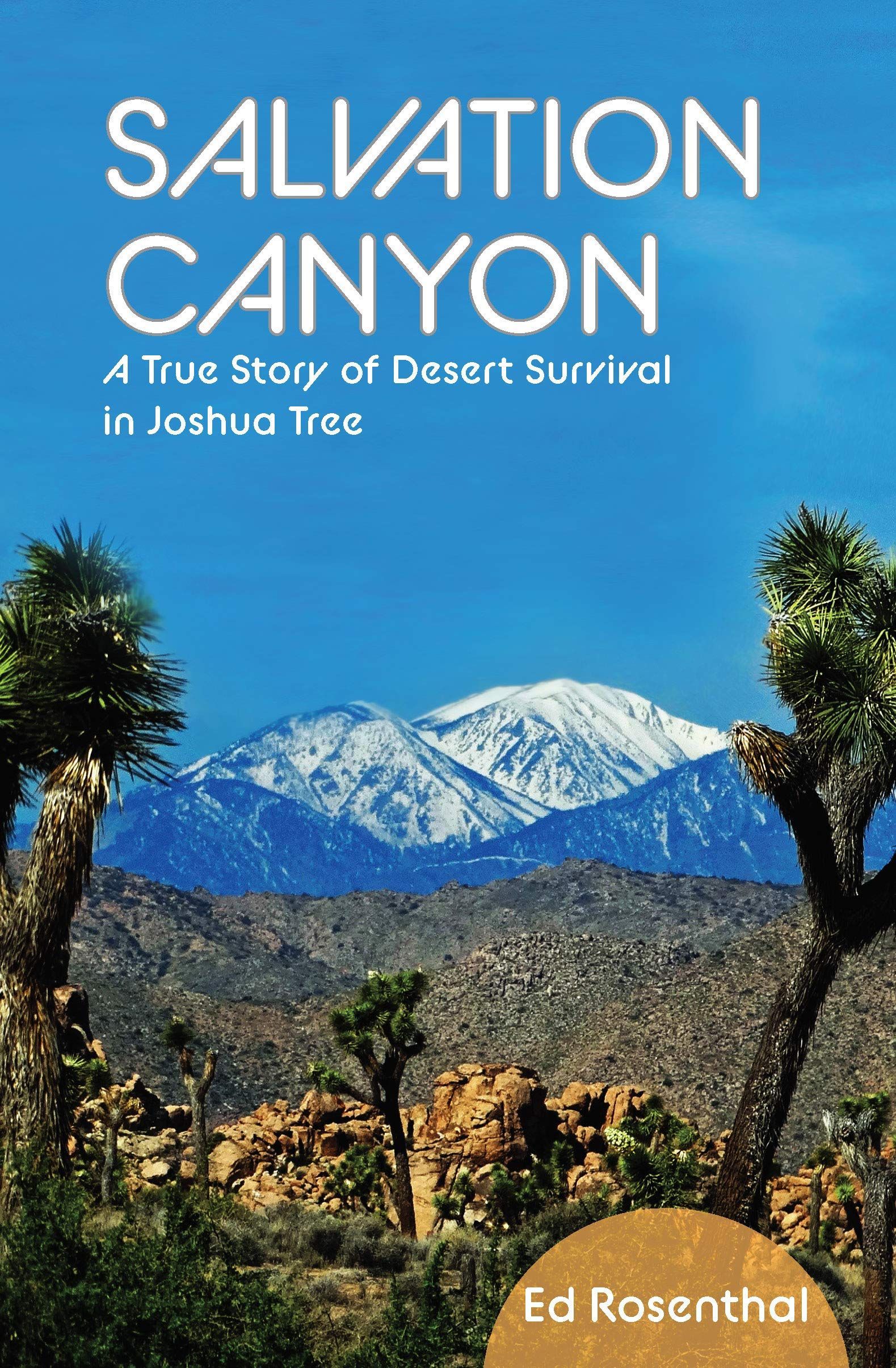

Salvation Canyon by Ed Rosenthal. DoppelHouse Press. 176 pages.

The ancient Poets animated all sensible objects with Gods or Geniuses, calling them by the names and adorning them with the properties of woods, rivers, mountains, lakes, cities, nations, and whatever their enlarged & numerous senses could perceive.

— William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

¤

ON OCTOBER 5, 2010, reporters surrounded Ed Rosenthal at Clifton’s Brookdale Cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles. By all normal reckoning, he should not have been there. He should have been dead.

The week before, Ed — a commercial real estate broker, published poet, and avid hiker — had taken a solo hike in Joshua Tree National Park to celebrate the sale of the Clifton’s building, which he had just brokered. He took a wrong turn, got lost in a maze of canyons, and miraculously survived for six days without water in 110-degree heat. “I stayed calm and focused,” he told the Los Angeles Times at the press conference. “I did not get excited because if you do that then you really just drop dead.” (As a publicist, Ed’s sometime hiking buddy, and fellow writer, I had scrambled together the press conference.)

When others might have succumbed to panic, Ed’s clear mind was his salvation. Now, 10 years later, that clarity beams through his new book about the experience, Salvation Canyon: A True Story of Desert Survival in Joshua Tree. Retracing his steps, Ed identifies each arroyo. Gives them names. Replays the colors and textures of sand and shrubs. The depictions are 4G, hyper-real, exact. They rivet you in Ed’s engrossed mind and dying body. All in simple, direct prose.

That would be astonishing enough. But something primordially creative also erupts from his hell. Something that lifts Salvation Canyon above the survivor-memoir genre and touches on the elemental power of consciousness. Ed flows back and forth through time (from boyhood and family memories to his present disaster). He has visions of a 15-foot Christ figure, Hebrew verses levitate him in a “wispy funnel of clouds,” and a procession of medieval warriors arcs across the sky.

Compellingly, he “animates” the desert. The intensity of a psyche inscribing itself on its surroundings recalls the “ancient poets” described by William Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Possessed of a poet’s sensibility, death breathing down his neck, Ed’s senses enlarge. He performs that essential act of human imagination: mythmaking.

A horsefly perches on his arm and, amazingly, becomes his close companion for the final four days of his ordeal, following him from rock to rock. The moon, the constellation Orion, a personified acacia tree — Ed subsumes himself into all these “friends.” He lives Blake’s apprehension that the gods reside within. The higher self sees that they are human projections. Ed communes with them, as when he details the looming Christ figure:

His eyes desired to help me, to assist me. His pleated skirt was well pressed and held close to his slim waist by a simple leather belt. He emanated peace. Speaking the first words I had spoken in six days I asked him, “What should I do?” I waited for something, and the desert responded. A ray of light hit his face. The sky turned blue.

As a Jew, Ed now likes to joke about this apparition when he does book readings: “I’m really cutting out some potential sales.” But back in the moment, it prompts a boyhood memory of Hebrew school, part of a series of self-forgiving flashbacks, a wise judge pardoning a prisoner. Death is upon the poet. Whole chunks of memory jerk into focus, then merge into his oppressive present — almost a reverse Proust-effect. It’s not the eruption of a buried shock. The shock is now.

Ever a writer, in the final hours before rescue, he puts a pen to the wide brim of his hiking hat. He composes a will, directing his wife Nicole and daughter Hilary on how to plan his wake.

“Writing the names of my friends, I felt better. As each name brought a different memory, my mind separated from the loneliness of my body on the rock.”

¤

A memoir of personal disaster tests the limits of words. How is a hellish experience different for a poet versus a non-writer? Is language an ally? Or does death negate language and its deceptions?

Questions such as these baffled the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot in his 1980 book The Writing of the Disaster (and many readers who have tried to decipher his dense, circular aphorisms). Death, like the future, is a fleeting concept, not a present reality. It never arrives. “In death,” writes Blanchot, “one can find an illusory refuge: the grave is as far as gravity can pull, it marks the end of the fall.”

Fitting, then, that death doesn’t come for Ed. At the final moment, when he is “settling into” the rock wall of Salvation Canyon, “about to become part of it,” the search-and-rescue helicopter lands. He hears a voice: “Are you that Rosenthal that’s out here?” Later on, he deadpans: “It seemed intensely funny, as if I would answer, ‘No, I’m not.’ or, ‘No, he’s in the next canyon.’”

It took 10 years for Ed to write of his disaster. The event itself crystalized his years on earth. And it proved that it’s a good thing he’s alive and writing.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jack Skelley is the author of the novel The Complete Fear of Kathy Acker (Semiotext(e), 2023), and Myth Lab: Theories of Plastic Love (Far West Press, 2024). Jack’s other books include Monsters (Little Caesar Press, 1982), Dennis Wilson and Charlie Manson (Fred & Barney Press, 2021), and Interstellar Theme Park: New and Selected Writing (BlazeVOX, 2022). Jack’s psychedelic surf band Lawndale released two albums on SST Records, and has a new album, Twango.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Playing the Long Game: Frank Bergon’s “Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man: The New Old West”

A new book about what’s left of the Old West in the San Joaquin Valley.

Blowing the Philosopher’s Fuses: Michel Foucault’s LSD Trip in the Valley of Death

James Penner takes a trip through “Foucault in California” by Simeon Wade, which chronicles the day when a great French philosopher blew his mind.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!