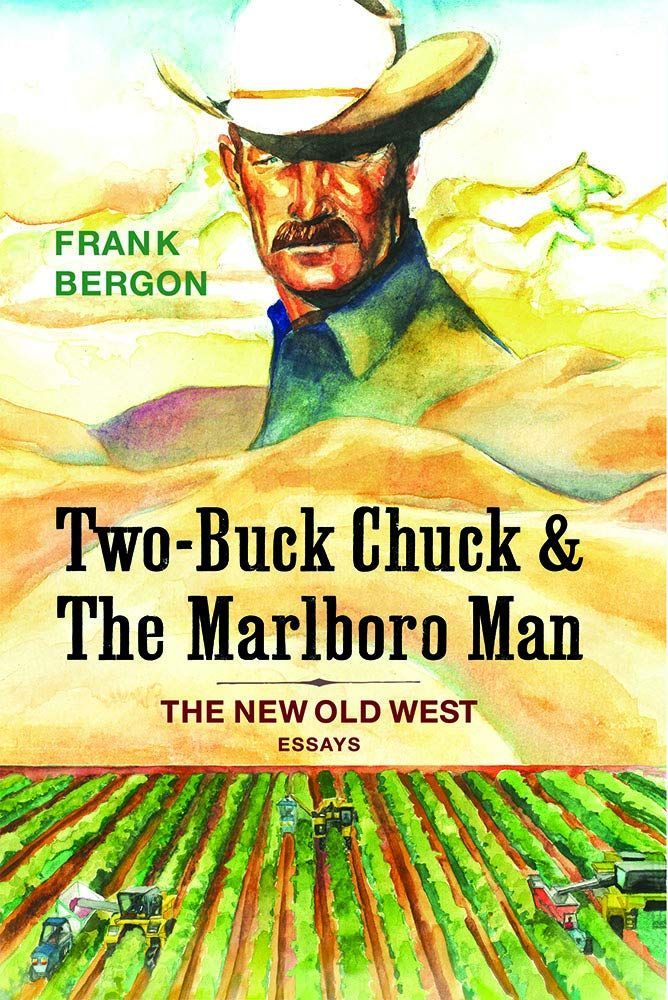

Playing the Long Game: Frank Bergon’s “Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man: The New Old West”

A new book about what’s left of the Old West in the San Joaquin Valley.

By Aris JanigianDecember 2, 2019

Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man by Frank Bergon. University of Nevada Press. 264 pages.

I WAS BORN AND RAISED a farmer’s son in Fresno and currently live here, working seasonally in the wine industry. But Los Angeles was home for most of my life, and whenever I learned that friends were heading to San Francisco, I’d suggest they take Highway 99 through the San Joaquin Valley instead of Interstate 5, which skirts the valley to the west. The 99 is a little longer route but so much more colorful (which isn’t necessarily to say “scenic”).

No one ever took me up on my suggestion, and they didn’t have to explain why not. After all, their impression of the middle of the state, de rigueur for Angelenos, is that gun-owning, pro-Trump types live there in dusty, beat-up towns with ugly names — Arvin, Alpaugh, Delano — that reek of cow dung. The valley’s fields are green but also monotonously endless, and none of its vineyards are rolling and soft on the eyes. Sure, it’s part of California, but not really “of it.” These scoffers know, in the abstract, that this is where the huge majority of Californians, and a good portion of the entire country, gets its food, but aren’t all those mega-farmers in the middle of the state also stealing precious water from salmon and smelts? The scoffers would much rather chat about their local farmers’ market, urban garden, or at least Whole Foods.

In fact, those mega-farmers are, for the most part, simply proprietors of small farms that, over a generation or two, have grown big. And, true, we’re talking about thousands of tons of tomatoes or almonds, and wells several hundred feet deep, and chemicals siphoned out of 250-gallon totes to keep mold and an array of devastating and exceedingly perseverant insects down; but if it weren’t for the sheer scale and efficiency of farming in the San Joaquin Valley, only the rich in this state could afford a melon or a peach.

Neither, for an office party, would we have the option of picking up a case of Charles Shaw wine — which is precisely where Frank Bergon’s storytelling begins in his new book, Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man. As it turns out, Fred Franzia, founder of said winery (a.k.a. “Two-Buck Chuck,”), went to school with Bergon in Madera, a city about 20 miles north of Fresno. Now, decades later, they’re at a coffee shop, it’s midmorning, and the writer is trying to tease out of the winemaker the explanation for his mind-boggling success.

But before the interview commences, Fred wants a drink. At that hour the bar is closed, so he asks the waitress for tomato juice and Tabasco, so that he can at least put together a virgin Bloody Mary. Fred has a winemaking pedigree — Ernest Gallo was his uncle, and Franzia of box-wine fame was his family’s operation — but after the latter was sold to Coca-Cola, Fred was left out in the cold. So, along with his brother and cousin, he started Bronco Winery in 1973.

Their focus was buying and selling bulk juice and wine, which they custom-crushed and bottled for other wineries for nearly 30 years before launching their own brand. Plenty of time for Fred to firm up his conviction that all that fancy talk about wine — the soil and wind and slope of vineyards, the delicate rays of light, the $30 tastings, the lengthy descriptions by sommeliers groomed at whatever institute — was mostly bullshit.

Although more wine grapes are grown in the San Joaquin Valley than anywhere else in the state, it is nearly axiomatic among vintners that nothing good can come of those grapes — where you get more like $400 a ton for Cabernet versus $4,000 in Napa — other than what they call “jug wine.” Fred set out to prove them wrong, and by putting Charles Shaw wines to the test in blind competitions, he did it fair and square. He won one prize after another (Bergon cites the surprisingly large number of them). But still, even if Franzia got the last laugh on taste, at $1.99 per bottle, when the bottle itself and the cork probably added up to a buck, was he really laughing all the way to the bank?

Franzia is loath to give up his trade secrets. Virgin Bloody Mary in hand, he bobs and weaves around the question, but eventually an answer takes shape: squeezing pennies out of wine boxes, in-sourcing bottle production, growing the grapes, bypassing distributors — all that helped turn Bronco Winery into one of the most profitable winemaking ventures in American history, an operation that grew so vast and fast that, before long, Franzia had become the largest vineyard owner in the United States.

Bergon, who lived on a farm near Madera, knows this terrain well — although he left it more or less as soon as he could, heading east to Boston College, then to Harvard for a PhD, before landing at Vassar in New York, where he taught English literature for most of his career. In other words, he spent most of his life away from home and these homespun characters, but they never quite left him.

This generous-hearted book, without a whiff of cynicism, is, ultimately, a clear and quietly crafted meditation on how much has been lost of the Old West, even in the two generations since Bergon was a kid. But it also captures what of the Old West has been preserved down to this day, in the likes of rancher Mitch Lasgoity; or David Mas Masumoto, who grows some of the best-tasting peaches on the planet; or the cattlemen Clay and Dusty Daulton; or Bergon’s old high school friend, winemaker Marko Zaninovich. Notice the surnames: Basque, Japanese, Okie, and Croatian, respectively. Over the course of this book, Bergon will also introduce us to Italians, a black ranch girl, a Native American, and even a Korean woman whom Bergon first meets on a plane. Their idioms, slang, twang, and pauses that drift into self-effacing chuckles (“Those [from the Valley] subjected to laughter are expected to laugh at themselves,” Bergon observes) are music to Bergon’s ear, which is perfectly tuned to them in a way that only a native (who also happens to be a first-class writer) can be.

But there’s a surprising theme developing here, and at one point, Sal Arriola — an undocumented farm laborer’s kid who now runs Franzia’s 40,000 acres — comes out with it: “Black, brown, blue, it didn’t matter,” Arriola says. “We had a mixed bag: I had Latino — Mexican — friends, like Omar Galina who went on to Yale and Jesús Rodríguez who went to Stanford and is now a doctor in Fresno. The race card was never there.”

Not every country has a tech, finance, or moviemaking sector, but every country — and most of the United States, in fact — has farming at one scale or another. So migrants and immigrants alike who want to farm naturally come to the San Joaquin Valley to take advantage of a nearly impossible combination of factors that make it the most fertile and productive agricultural expanse in human history. And whether those farmers are Hmong, Sikh, or Swede, the vagaries of almighty nature and the even more almighty market will eventually level the playing field, humble, and occasionally render each and every one of them dumb. Hail in mid-May can wipe your crop out — or, for a recent example, Lodi Zinfandel that went for $700 a ton in 2016 brought $100 this year, not even worth the picking costs.

And then there’s the drought, which Bergon covers in this book with admirable balance and finesse. Though technically over, it’s only a matter of time before the next nasty stretch of dryness hits. Thirsty cities, regulators, environmentalists, and, of course, farmers themselves, who unwittingly drained the aquifer for decades, are all putting into question the survivability of this great American project.

This would be a gain to some, and an apocalyptic loss to others. Not only because we’d lose the source of fresh fruits and vegetables and nuts (the San Joaquin Valley is one of the only places in the world where pistachios and almonds grow), but also, for Bergon, because we’d be losing a distinct way of life: a fearlessness in the face of hard work; an acceptance of nature’s indifference, combined with attempts to outflank it; a skepticism toward abstract solutions and sudden demands for change; a high tolerance for risk; and a temperament to endure setbacks without complaint, with irony and laughter to ease the pain.

It’s a way of being that’s epitomized by Darrell Winfield, the “Marlboro Man” and lifelong friend of Bergon, whose story ends the book. A Maderan cattleman whose operation went bust in 1964, Winfield moved to Wyoming, where he worked on the Quarter Circle 5 Ranch. An ad agency looking for footage for “Marlboro Country” spotted him; they took some pictures and, before long, wanted him to fly out to Texas for a shoot. But he told them he was “pretty busy shipping cows,” so “if you boys want to take my picture, you better come out here.” Intense, handsome, relaxed, he was soon the “face” of Marlboro cigarettes, and by the time he’d retired from the gig, he was, according to some accounts, the most photographed man in history — so iconic a figure that photographer Richard Prince would “appropriate” his image for a show at the Guggenheim.

Barely any of this bounty would redound to Winfield’s benefit. Though he was paid well, it was a pittance compared to what others similarly well-photographed earned. Maybe it didn’t matter to Winfield because, straight through the shoots, he remained a ranch cowboy, and later an independent rancher.

I’ve worked with and known many of these Maderans, who regularly meet up at a certain coffee shop for donuts at 6:00 a.m. to share stories, worry over the weather, and size up the crop. Rarely, though, can you get them to talk about their failures or, even more rarely, their successes, so what Bergon is able to draw out of them is no mean feat. One of my closest friends farms 5,000 acres of wine grapes and drives a 10-year-old pickup with nearly half a million miles on it. Franzia, whom I know, uses what amounts to a few old trailer homes in Ceres, California, for his “corporate headquarters.” The wooden chairs around his conference table are what you might expect to find in a Waffle House circa 1980. No need to fix or replace what isn’t broken.

Farming and ranching are long games — you can’t just lift trees or vines or even cattle and drop them somewhere else — and so this way of life facilitates unusually long-lasting relationships. This is the most important message, I believe, that Bergon hopes to convey to us about the Old West. Winfield, in spite of his fortune and fame, “still went to work every day. He still wore the same clothes. His friends from past years were still his friends.”

The last time I was at Bronco Winery, I noticed, above the doorway heading into Fred’s office, a bleached-out color photograph, from probably 45 years ago, of Fred with two farmer friends. One of them is dead, but his family continues to sell thousands of tons of grapes to Fred every year. So does the other friend in the picture. No contracts were signed, and in fact, there’s no talk of price per ton until after the harvest is over. After a huge lunch the family matriarch has made, and only after all their bellies are good and full, does the issue of money (invariably in the millions) come up, and not exactly for discussion: such is the trust, built up through frost and fog and withering heat, through the hell and glory days, that Fred tells them what he can pay that season, and that’s that. None of them would dream of having it any other way.

¤

LARB Contributor

Aris Janigian is the author of five novels, and co-author, along with April Greiman, of Something from Nothing (2001), a book on the philosophy of graphic design. For his first novel, Bloodvine, Janigian was hailed by the Los Angeles Times as a “strong and welcome new voice,” and over the course or four subsequent novels, he has plumbed the American experience, from the struggle of 1920s immigrants to the neurosis and decadence of contemporary culture. This Angelic Land, set during the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, was called “today’s necessary book” by critic D. J. Waldie, and Janigian’s Waiting for Lipchitz at Chateau Marmont, about a screenwriter who goes from riches to rags, spent 17 weeks on the Los Angeles Times bestseller list. In his recently released Waiting for Sophia at Shutters on the Beach, Janigian broaches sexual politics and “rape culture,” one of the most heated issues of our times. Aris Janigian has pursued a three-pronged life and career, as a writer, academic, and, following in his father’s footsteps, a wine-grape packer and shipper in Fresno, California, where he currently lives. Holding a PhD in psychology, Janigian was senior professor of humanities at Southern California Institute of Architecture, and a contributing writer to West, the Los Angeles Times Sunday magazine. He was a finalist for Stanford University’s William Saroyan Fiction Prize and the recipient of the Anahid Literary Award from Columbia University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Mild, Mild West: On “Dreams of El Dorado: A History of the American West”

A one-volume history of the American West reads too much like a movie we’ve already seen.

Reverse Cowboy

Disentangling fact from myth in the figure of the American cowboy.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!