A Melancholic Muscle: On Jon Lindsey’s “Body High”

Gabriel Hart plumbs the depths of “Body High,” a debut novel by Jon Lindsey.

By Gabriel HartMay 1, 2021

Body High by Jon Lindsey. House of Vlad. 188 pages.

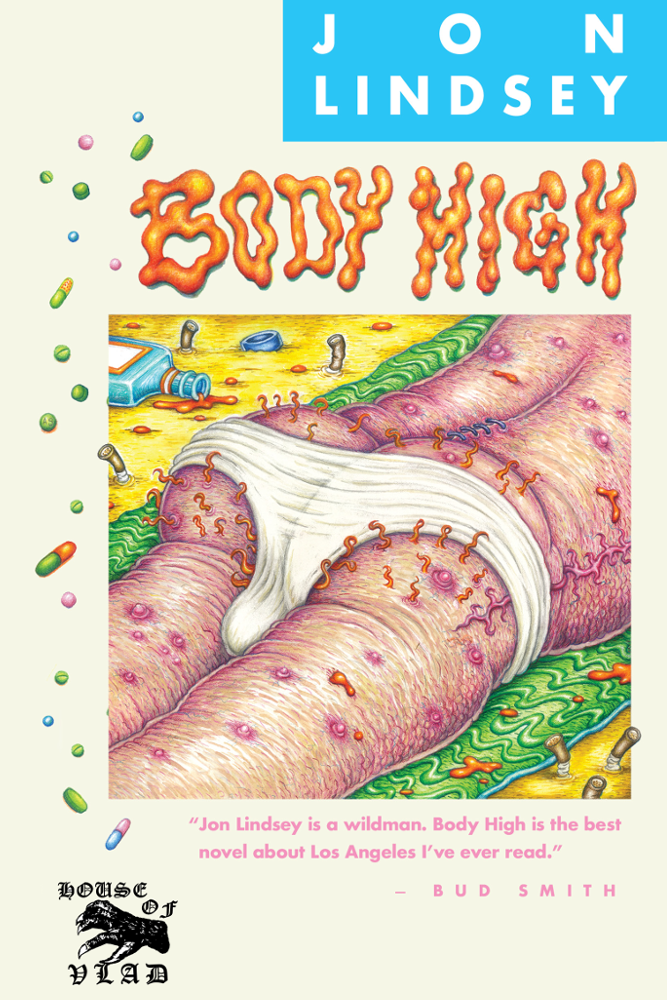

ONE CAN’T RESIST starting with the cover. It’s an initiation of sorts: the Garbage Pail Kid style vandalizing an immaculate bootleg of Vintage Contemporaries. The rashy pastels depicting a diseased sunbathing dad bod riddled with boils and worms might send a tame reader running, yet Los Angeles–based artist/designer/fabricator Andrew Sexton’s deceitfully low-brow art could hang on the same gallery walls as high-priced pieces by Robert Williams and Ed Roth, so some may open Jon Lindsey’s debut novel, Body High, with their judgments already impaired.

Much like Chandler Morrison’s recent Along the Path of Torment, Lindsey’s Body High is a true Los Angeles novel, capturing the city in its current umpteenth stage of class-damaged rigor mortis. The books are staggering, synchronized companion pieces, whose conflicted protagonists become enamored with Lolita-esque teenage girls who challenge their brittle moralities. In both novels, the attraction is a trigger of awakening and recollection of the abuse to which the men themselves have been subjected. The authors have chosen a precarious route to get to these epiphanies, but is there a comfortable way to deal with uncomfortable truths?

Body High’s first-person protagonist is Leland, a barely functioning white drug addict whose arrested development includes irreconcilable mommy issues, exacerbated by her recent death. The book opens at her funeral, where Leland is accompanied by his best friend/drug connect “FF,” an emotionally removed Lucha Libre wrestler professionally known as Freedom Fighter. The two are just another pair of brokenhearted men at a ceremony suspiciously bereft of women; the other attendees are all mom’s ex-boyfriends. None of these men could compete with drugs, however, revealing the umbilical roots of Leland’s addictions. When it comes time for the pallbearers’ task, Leland, incurably clumsy, slips and loses his grip on the casket. It hits the ground hard, and the top flies open to reveal not his mother but Jack Nicholson. I’m sorry, a Jack Nicholson impersonator.

This sounds ridiculous because it is. But what keeps Body High from falling into complete gonzo-absurdity is Lindsey’s devastating prose, a melancholic muscle that keeps the narrative taut even as we watch Leland crumble. Besides, anyone who’s lived in L.A. long enough can attest to the city’s surrealism, how we stockpile stories that begin with “you’re never gonna believe this.” It’s one of the perks of living among the Industry’s smoke and mirrors, in the cruel overlap of social classes, with everyone’s hands in the same cookie-jar of opiates.

Actually, there is a girl at the funeral. “U won’t believe whos here,” texts FF. Jolene, an acne-faced red-haired teenage girl surfaces, screaming his name. Leland is stunned, awkward, with no clue who she is — until she spells it out: “Your auntie!”

Guess who else likes drugs? The three instantly fuse into a self-contained, suffocating crowd of codependency, inviting tragedy with their every step to evade it. Alternating between Oxy and amphetamines, their sense of balance is permanently out-of-whack — and made worse by Leland’s infected butt cheek, a wound he sustained from a botched clinical trial. The festering sore becomes not more than a distraction — it achieves its own character status, a toxic two-way portal: as Leland poisons himself from the outside in, the sepsis threatens him from the inside out.

But let’s back up — Jolene, a teenaged drug addict, is Leland’s aunt. The math is challenging, but not as difficult as the weight you carry when obsessing over the missing link here: who is Leland’s father, and what has he done to create this twisted-root family tree in flames?

We know Jolene has grown up way too fast, the way she chugs wine, begs for drugs, and mouths off when she doesn’t get her way. Yet we are reminded just how young she is by her social media vanities — just another addiction. Her and Leland’s accumulated traumas begin to overlap, a Venn diagram of dysfunction steadily eclipsing until they both get too faded and … They both deny anything actually happened, because that’s what they’ve been taught to do by others who should have known better. And so the trauma bond is tempered, especially for Leland, who sees Jolene as his last connection to his mother. Only Jolene’s accustomed to swiping left, and eventually goes for FF, leaving Leland trapped in his head, where we keep him largely sympathetic company.

Because Body High is a tragic odyssey through the streets of our unwelcoming, inconvenient, misunderstood city, it’s naturally a comedy of errors and we are allowed to laugh. When FF finally puts down his drugs and guns, it’s for his wrestling rumble with “The California Kid.” Whether it’s the announcer’s actual word salad or Leland’s drug-addled perception of it from the stands, Lindsey’s skills had me howling out loud as FF’s opponent enters the ring:

He is the Sensualist, the Essentualist, the Bigamist, the Biggermist, the Drive-By Amorist, the Sentimental Recidivist, the Post-Feminist Gynecologist, the Sizemologist … Snoop Dogg’s Herbalist, L. Ron Hubbard’s Psychologist, Magic Johnson’s Antiretroviralist … Silicon Valley’s Anesthesiologist, San Francisco’s Progressive Proctologist, Wine Country’s Gastronomist, Surf City’s Hydrologist, the Nude Beach Sartorialist, West Hollywood’s Stylist, the City of Angels’ Evangelist, Tinseltown’s Metallurgist, the Rose Parade’s Florist, the Uncut Semiticist, the Sunshine Supremacist, the Land of Fruits and Nuts Nutritionist, THE CALI—FOR—NIA—KID.

If that doesn’t stoke your Golden State pride, get the hell out of here.

The comedy accompanies but doesn’t lessen the tragedy. As Leland toggles between unrequested father/big brother/estranged lover/the most distant nephew to Jolene, it’s her impending mortality that finally snaps the two men into adulthood. While it’s hard to discern where the guilt belongs, they feel responsible — during FF’s re-up, Jolene indulged in tainted cocaine and now she’s in the hospital with kidney failure. (Lindsey is street savvy in his research here. Jolene’s blood work returns showing PCP, borax, and livestock de-wormer — and I recall not long ago when Levamisole was making headlines as the dangerous new ingredient in coke-cutting, sending its users into toxic shock and other life-threatening conditions.) Jolene needs a new kidney, and the perfect match is more than a Tinder-swipe away. When the black-market organ harvesters fail them, Leland reveals his darkest secret yet — that he is a father — in the hopes that his estranged five-year-old daughter Brooklyn might serve as a donor. All they have to do is kidnap her.

Body High is a genre-defying work, and the plot device works here — not a jarring left turn so much as a display of Lindsey’s versatility. When Brooklyn goes despondent in the getaway car, weeping that she wants to go home, Lindsey speaks volumes through Leland’s deadbeat attempt to console her as an anti-Father: “The secret about home is that it actually doesn’t exist. Home is just a foundational state of being. You’ll spend your entire life trying, and failing, to return to it.” It’s obviously too heady for Brooklyn, but it’s somehow exactly what the rest of us needed to hear at this point on the arc. What keeps Brooklyn from going under a rogue knife is a vital pitstop at the luxurious house of a man named Leslie (relationship redacted, though it’s safe to say he’s the boss at the end of the game). Of him, Leland thinks: “Immediately, I’m cooperating. I’m submitting to the weight of need in his voice. And even as I do, I realize this is how he manipulates people — that his power comes from need. This is how the abuse has been passed down, how victims are kept in check.”

It’s not a happy ending, but Lindsey’s sleight of hand assures it’s a resolved one. Just as in Morrison’s Along the Path of Torment, the action leads to the beach — the edge of the world when you’ve gone off the rails. For better or worse, Leland must fully realize abandonment before acquiring what he’s looking for, an insight he’s been carrying with him since his mom’s funeral: “To truly heal, I need to cut off my family.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Gabriel Hart is the author of the literary-pulp collection Fallout from Our Asphalt Hell (2021), the poetry collection Unsongs Vol. 1 (2021), and the dipso-pocalyptic twin novel Virgins in Reverse/The Intrusion (2019). He lives in Morongo Valley in California’s high desert and is a regular contributor at LitReactor and The Last Estate.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“The Faster You Pour It Down”: On Charles Bukowski’s “On Drinking”

Anthony Mostrom gets a taste of “On Drinking” by Charles Bukowski, edited by Abel Debritto.

With Love and Squalor: On Lili Anolik’s “Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A.”

Lauren Sarazen praises “Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A.” by Lili Anolik.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!