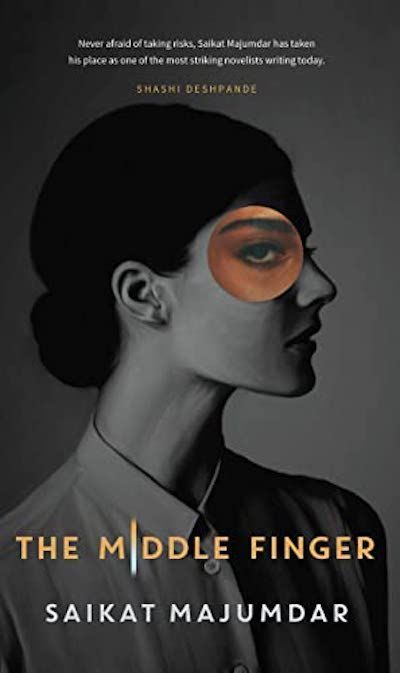

A Masterpiece of Subtlety and Gentle Ellipsis: On Saikat Majumdar’s “The Middle Finger”

A sparkling new novel from India about the work of poetry and the poetry of work.

By Lantz Fleming MillerJanuary 30, 2022

The Middle Finger by Heather Morris. Simon & Schuster India. 240 pages.

SAIKAT MAJUMDAR’S new novel, The Middle Finger, published in February 2022 by Simon & Schuster India, is as rich and intricate as a tapestry, yet pleasingly simple and seemingly artless in execution.

The central character, Megha, appears almost nowhere but at her endless work. At first glance, the workplace might not seem the most appealing subject matter for a novel. Why spend our precious reading hours after struggling through the nine-to-five by reading about a nine-to-fiver? Yet The Middle Finger succeeds deliciously in so melding the life of work and the stuff of life as to be impossible to separate them. This work about work works so well in creating an artist’s world that it provides perfectly plausible, in fact quite good, examples of Megha’s poetic output.

This remarkably endearing lead character would, if she could, make her entire life into poetry, which would be her sole work. But at least two harsh realities set in. As most poets know, the work of poetry alone can rarely supply food and shelter. So Megha must take on the dreaded chore of teaching freshman comp. She does this chore well despite the grumpiness she keeps to herself, and she is actually a fun instructor, much favored by students.

But the other harsh reality may be more unsettling. Other people in her life want to take — even steal — her work for their own purposes. One man choreographs her poetry as a silent dance, where supposedly his movements say what her poems do. Other folks exploit what they see as the potential political import of her poetry. These people do not quite see her for what she is — the hermetic individual she creates and animates, as though it were her secret friend. Even those who hire her at a new university in India seem, in their doggedness to win her, not to notice that they are using her for their own ends, even if not entirely unjustly. Then she meets Poonam.

This dedicated Protestant is one of the most down-to-earth and least pretentious persons in Megha’s life. Poonam arrives during Megha’s transition between her United States sojourn and her return to Delhi. She injects herself into Megha’s new household, and Megha hardly rebuffs her. First appearing as a friend of some men who are installing new furniture in Megha’s apartment, Poonam at once acts comfortably at home, serving the tea for Megha and the movers. Within a few moments, Megha detects a distinct sensuality: “Poonam stepped closer to her. Megha could smell her hair, its rusty oiliness.” By contrast, the “movers’ male odor floated all over her flat as they settled the furniture, a lazy, disagreeable smell.” Minutes later, Poonam “poured a third cup and held it out to Megha. Megha looked at her. Something shifted inside her, like a small, pleasurable landslide.”

Although this is the first time Megha and Poonam meet, the reader has met Poonam already, if unbeknownst, in the novel’s first paragraph. At first incognito, Poonam provides three prose poems that are distributed throughout the text, prefacing several chapters. The first of these, “The Death Shaped Window,” seems to serve as a prelude to the first four chapters, while “The Map of No Country” prefaces the next three chapters and “God-fight” comes before the last 17 chapters. While the rest of the text is in the third person, these preludes are in the first person — in fact, are narrated by Poonam, though the reader cannot readily know this fact before reaching chapter 11, which begins to hint at Poonam’s poetical nature. These preludes flesh out Poonam more deeply than does her own fancying of herself as a humble house server (to avoid the harsher term “house servant,” although modest Poonam would probably allow that term for herself).

These preludes also hint that Poonam has learned much about herself in a kind of osmosis from Megha. But they also protect Megha from charges that she has taken advantage of Poonam since this is a special role Poonam has entirely created for herself. Poonam has never been Megha’s student in any ordinary sense, as in a school or poetry workshop. Poonam’s insistence that Megha take on that role initially baffles Megha, but she comes to find something life-changing in their complex relationship, to feel that “this artless, honest, unsophisticated forest dweller” has helped to peel off the layers of distance that have usurped her work and self. Will she have a chance to flourish in this new condition? An epigraph offers a hint, speaking of a member of a certain tribe who has lost a thumb while meeting a challenge but can still “shoot arrows using his middle-finger and his forefinger.” Perhaps, if Megha is to thrive in her new condition, Poonam will fill in as Megha’s now-deft middle finger. As a result, Poonam becomes the honest, astounding poet she feels is inside her.

Majumdar excels in his characterization of the artists, writers, and university administrators who populate his story. These characters are very much their own persons, not mere stereotypes. They do wear Megha down, but her inner nature is too strong to let them much affect her. Her relationship with Poonam, the reader feels, helps to bolster Megha’s capacity to assert herself in the work arena. Another striking feature of the book is Majumdar’s sculpted language, at once sensual and sharply honed. Each sentence is a poem in itself, and some especially glimmer with insight: “Dissertations are full of deceit. It takes time for them to love you back.” Or: “A good teacher is like a serpent, no? Holds you in a spell with the eyes.”

The narrative structure, with Poonam’s poetic voice interspersed amid the third-person prose, strengthens the novel’s overall poetic quality, as do the excerpts of Megha’s own verse, which is so good and so convincingly hers that the reader would love to find one of her volumes. Beneath these pleasing aesthetic facets run political undercurrents, the most prominent being the theme of teacher-student harassment. Put bluntly: Is Megha harassing Poonam by entering a relationship with her that goes beyond the academic? After all, Poonam refers to Megha as her teacher. As Poonam’s poetic preludes attest, her own voice is strengthened by their relationship. Is such influence a bona fide education, even though not formally conducted in a classroom? The novel so stealthily lets this aspect of the scenario unfold that Majumdar never seems to be preaching or taking sides.

Other social and political issues, relating to ethnicity, gender, and class, arise, but quietly. All these topics simply unfold, naturally, in a multinational setting where sociopolitical questions have become so self-conscious as to be part of the unavoidable fabric of social life. Yet this astonishingly complex yet accessible narrative is a masterpiece of subtlety and gentle ellipsis, with Saikat Majumdar wielding an ingenious yet unobtrusive control of style and story. The Middle Finger’s intriguing, if often critically presented, setting — the international world of literary coteries — should help it appeal to a wide array of readers. Indeed, any connoisseur of excellent fiction will certainly want to seek out a copy of this beautiful, chiseled, poetic novel.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lantz Fleming Miller completed an MFA in writing at Columbia University and a PhD in philosophy at City University of New York Graduate Center. He has taught in a number of universities in the United States, France, The Netherlands, and India and has published dozens of research and review articles in professional journals, on political and ethical theory and aesthetics. He has also two novels out from Grand Viaduct, City Limit (2012) and Beholt, the Man (2015).

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Failed Success of the Postcolonial Reader

In India, English is the language of aspiration, of power and mobility.

Post-377: LGBTQ Literary Culture in India

LGBTQ fiction is blossoming in India following the decriminalization of homosexuality.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!