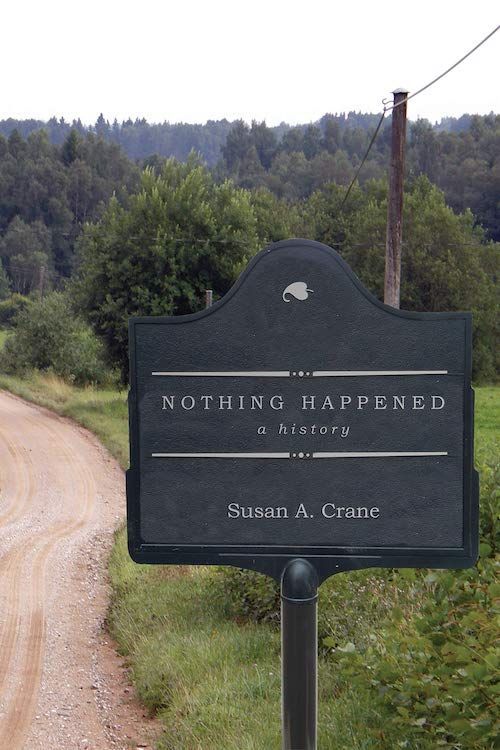

A Look at Nothing: On Susan A. Crane’s “Nothing Happened: A History”

Vesper North considers "Nothing Happened," a new history by Susan A. Crane.

By Vesper NorthFebruary 9, 2021

Nothing Happened by Susan A. Crane. Stanford University Press. 264 pages.

“NOTHING HAS CHANGED” is the eternal lament of reformers and idealists. It’s an especially loud one at the time when the United States’s worst elements — racism, know-nothingism, rampant selfishness — seem to be in a waxing phase.

The hopeless sentiment is easy to understand. But what never goes examined is the embedded assumption: What does “nothing” mean in a historical context? In her engaging book with a double-meaning title, Nothing Happened: A History, Susan Crane transforms the elusive concept of nullity into a biographical subject: the presence of the absence across centuries.

Crane draws attention to historical blind spots in pursuit of altering the reader’s perceptions about history and what constitutes Nothing — arguing that ignorance does not denote insignificance. “Nothing is always Something that’s been left as Nothing, whether in an abandoned space or a photograph, on a historical maker, or in memory.”

History, by reputation, is a dry subject. Nothing Happened is about the present just as it is about the past. “Paying attention to how memory happens in the present, how remembering is happening just as Nothing is happening, alerts us to the creation of historical consciousness” — prompting us to wonder how present experiences will be remembered. Crane asserts that Nothing is not the absence of activity but rather of acknowledgment.

The book is structured into three “episodes” of Nothing-ness, with an aim “to illuminate the utterly ordinary ways we refer to the past as Nothing.” She encourages the reader to think differently about history, not as a complete record but as a selective narrative that somebody thought to write down:

History is not the same thing as “the past.” The past is everything that has happened, whether it was recorded or forgotten, whether it lasted for eons or instants. […] History is what happens when we remember, study, and write about it.

Crane opens with the death of Luigi Trastulli, who was killed at a rally in 1949 in Terni. His name is unrecognizable, and the political turmoil of mid-20th-century Italy is not immediately familiar to the majority of the world, but his story is eerily familiar: Trastulli was shot in the back by police as he fled the outbreak of violence between the protesters and law enforcement.

“The communities of Terni enshrined Trastulli’s name in memory, not only because of his tragic death and personal connections to local people but also because of the way his killing remained an open wound,” Crane writes. He became a martyr, and then he was forgotten. Crane continues:

“Nothing happened to the guys who shot him” means that justice was not served. But in reality, it’s not true that “nothing happened” to them: The presumed perpetrators experienced quite a lot of life in the years that followed, just not jail time, and the survivors experienced a delayed and deferred future in which what was supposed to happen didn’t, over and over and always.

References to pop culture, such as Seinfeld and The Simpsons, make the book more accessible to a wide-ranging audience — a good thing, for this is a diplomatic attempt to help change the fatalistic narrative, especially when applied to victims of police abuse. She asks us to find solace in these moments, for “[w]hen those in power attempt to erase a group’s voice, Nothing remains but lamentation, protest, and resolve.”

Crane spends an exhaustive amount of time establishing this premise, which may tire the reader out too fast. She breaks the term “Nothing” down to rebuild it throughout the introduction and into Episode 1. But she hits her stride when she taps into the collective memory of the Holocaust:

Tattoos may be popular today, but the tattoo forced on Yosef Diamant was part of his dehumanization by the Nazis. Our skin lasts as long as we do, and tattoos last a lifetime. In this act of resistance against forgetting, the tattoo’s longevity, inscribed against the will of the victim, has been transformed by his family into a memorial. The victim’s granddaughter was worried that the Holocaust seemed like “ancient history” and that her generation “knows nothing” about it. In response to knowing Nothing, the tattoo speaks for the past — not only for the surviving victims and their families but also for the silenced victims who already lost their lives.

The desire to testify about the past, to express historical consciousness against the evaporating effects of ignorance, is producing tattoo art beyond concentration camp identification numbers.

I was reminded of an internet furor from 2019 regarding a tattoo that Chrissy Teigen had inked on her forearm, a minimalistic line of family birth dates, which some thought tastelessly mimicked those given to prisoners in Nazi concentration camps. The Instagram firing squad shot mercilessly at Teigen, saying that the tattoo had “really strong Holocaust vibes.” Others commented with “I think this would make any Jewish person very uncomfortable even if unintentionally” and “Is anyone else a little bothered by the fact that she got a series of numbers on her forearm? Is the Holocaust really that far removed from our reality?”

Then unlikely allies broke through the woke mob’s righteous indignation: members of the Jewish community: “As a Jewish person who lost family in the Shoah, THIS tattoo is absolutely NOTHING like the numbers which were ground into the skin of millions of people’s arms, Jews and non-Jews alike.” Another spoke in defense of Teigen, remarking that her tattoo was a “celebration of life” not a “mark[ ] for death.” Writes Crane:

In the past decade a trend in memorial tattooing has emerged. Grandchildren inscribe their grandparents’ tattooed identification numbers onto identical places on their forearms, thus bearing powerful memorial testimony to the harm and trauma suffered by loved ones.

This trend emerged partially out of fear that people would forget the past horrors of family members’ mistreatment, torture, and death — creating “an ethical imperative ‘never to forget.’” Four of Diamant’s family members have tattooed 157622 on their forearms — the same number he received at Auschwitz 60 years earlier.

The stories of Trastulli and Diamant’s family are two of several forgotten stories retold at the beginning of Nothing Happened. The continuously shifting ground makes for a stirring read as she sheds light on obscure portions of history. Crane’s choice of subjects is not accidental — she draws parallels to current sociopolitical issues, relying on the reader’s pathos to generate interest.

But then the point again: “Knowing Nothing is not an excuse for ignorance.” What is unknown cannot always be helped, though “to ignore what you could know is a specific form of ignorance.” Such is the case with the perfectly named Know Nothing movement of the 1800s. As Crane describes,

[T]heir agenda was virulently anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant. Supposedly the party got its name from its original secretive practices: When members were asked about local chapters of the party, they would reply, “I know nothing.” By the 1850s the party had grown exponentially, and at the peak of its popularity in 1855, forty-three party members held seats in Congress.

Also called the Native American Party, despite having no indigenous members, the Know Nothing movement was “founded on protecting the privileges and rights of primarily Protestant white American men,” whose longevity required a perpetual state of ignorance. This chilling chapter in American history is all too reminiscent of the attitudes held by certain modern politicians whose rhetoric of intolerance is based upon knowing nothing about the people they disparage.

The coming of the Civil War challenged the Know Nothings’ blinders on approaches to governing; they “fell apart over the issue of slavery,” but their “legacy endured as successive waves of immigration caused Americans to implement quotas, identity protocols, and other restrictions on migrant civil liberties.”

An American author whose book comes from an American publisher does not exclusively speak to an American audience. The ubiquitous themes of Nothing Happened avoid alienating the reader. Crane writes with the presumption that her book will be consumed by a diverse readership. She cites work by fellow historians, sociologists, and various artists from across the globe to contextualize her arguments, giving her book the flavor of a lecture transcript from a chatty professor who likes to go on tangents. The back cover promises “a provocative and witty discussion,” though her occasional attempts at humor misfire in the dry air of her authorial voice.

While the topic of Nothing is thought-provoking, she runs the risk of losing the reader as she jumps subjects. I found my focus waning as Crane discussed how “Nothing is the way it was” in Episode 2. In this episode, the editor’s clumsy approach to multimedia derailed my attention. Further, having studied the history of film and photography, I know the subject to lack allure. Crane’s approach to the topic does not translate well onto the page:

In a nation that transformed itself no fewer than five times in one century, what does it mean, after all, to say, “Nothing is the way it was”? [Eva] Mahn photographed Halle, a city whose architecture was relatively intact after World War II, making its historical buildings all the more distinctive.

This is how it appears for portions of the chapter — text describing the photo to eventually be followed by the actual image. The organization of text and images lacks synergy with unfortunate frequency. This is not the author’s fault, but is avoidable — particular when there’s a fluidity in Episode 1 (also featuring photographs, drawings, and scans of other written material).

Among the photographs in Episode 2 is Roger Fenton’s The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855), depicting a hillside of dirt and rock. It appears to be a photo of nothing. “As a caption, the title provides context, but it works best for viewers who know the history of the conflict.” The rocks in the photograph are actually cannonballs — what Fenton has captured is death. He was tasked with documenting the Crimean War, and the resulting work holds little meaning without context. Crane describes that,

when the photograph appears to be of Nothing, making sense of it can overwhelm our senses and imagination, even if we care about the subject and already know something about it or even if it is aesthetically appealing. Ruins often have this appeal. But if we aren’t drawn to the visual image or are not engaged in the reasons it was made or is being seen, we will see Nothing of particular interest and merely register the visual elements: grass, road, hills, rocks, fences; colors, black, white; sloping angles, triangular sky.

The elementary lesson she teaches here isn’t gripping, but such is the nature of the book — the reading experience alternates between diverting and mundane. The strength of changing subjects is also its weakness in keeping the reader on board. Crane resists pressuring the reader. Instead, she trusts that empathy will develop organically.

Nothing Happened culminates with an argument that just because things didn’t turn out the way we wanted doesn’t mean nothing happened at all. It’s a hard pill to swallow but a necessary one.

Crane chooses her anecdotes well, especially in transhistorical terms. After boxer Joe Louis beat Hitler’s golden boy, Max Schmeling, the “German media coverage contested the results of the fight” — Schmeling had to win so white supremacy could continue to thrive. The election, in short, was rigged. Americans shamefully did likewise:

[A]s historian Paul Gilroy reminds us in Between Camps: Nations, Cultures and the Allure of Race (2004), white-black boxing was illegal in several states at the time. In his typically trenchant analysis, Gilroy demonstrates how one of the leading American newspapers offered a radically paranoid response to Louis’s victory. “Nothing had happened” at Madison Square Garden that night, according to the New York Times coverage; “the outcome was meaningless.”

Amid the bleakness, Crane’s passionate tone carries with it a modicum of hope: what is once lost can be found again. Nothing becomes something again, as in the case of a secret diarist who left behind a crucial account of the Third Reich:

Victor Klemperer’s diary remains a powerful testimony to the experience of Holocaust victims. He filled the intentionally blank book with his daily encounters with racism, anti-Semitism, and other forms of Nazi oppression. The published diary, I Will Bear Witness: A Diary of the Nazi Years, 1933–41, ends on New Year’s Eve, 1941, with determination against all odds.

The book wasn’t published until 1995, having been hidden in the East German archives.

When it has been decided that nothing happened, “we are actively remembering a historical event that we called Nothing.” Reducing something to Nothing doesn’t erase it — forgetting it entirely does. Crane suggests that, as a collective, people choose to remember or forget. Highlighting famous disappointments does not suggest that what followed was unimportant — that nothing happened.

“The singularity, the uniqueness of one story, does not cancel out others but must be seen, heard, and acknowledged if it is to have any bearing on justice in our understanding of the past.” Crane’s radical approach to the dissemination of history brings comfort against the seeming stagnation of the present. By sharing the past, Nothing changes, and by partaking in history, we become a part of it. “Reading to learn the story, sharing the story, remembering the story, repeating the story over and over […] this is the historian’s craft writ large.” Though it also becomes clear that Crane’s tiresome explanation of Nothing stems from the anxiety of an educator who fears that her students won’t get it:

One of my students asked me whether any Nothings became Nothing by not making it into the book. I was delighted by her perceptive question, please that she “got” the idea that Nothing was worth studying and that what got left out was still Nothing.

By encouraging the reader to look at Nothing as she has, Crane offers the reader the power to set the record straight. Teigen’s tattoo isn’t evidence of forgetting but the fear that we will. The spirit of the Know Nothings hasn’t been resurrected; it never left. Mahn’s and Fenton’s photographs don’t confuse; they help to promote a thirst for understanding.

History is a puzzle whose pieces are collected throughout time, where clarity is continually improving. Crane knows this and does not crowd her book or overwhelm the reader. Her patience remains consistent throughout, ensuring the reader’s arrival in the end regardless of their scholarly starting point. Nothing Happened takes time to digest and can be enjoyed a second time around: “[T]he first story is over and, in the present, you’re done with it; you have stopped listening or reading. That’s where collective memory steps in: Who else read the story? Who else remembers it?”

We are surrounded by Nothing — it’s everywhere, all the time. And “[t]his is what happens when I am thinking about Nothing: Nothing gets done.” Crane teaches the reader a way to view history. What we do with it is up to us.

¤

LARB Contributor

Vesper North is a writer and artist who teaches English and communication and is a member of the TAB Journal staff.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Galaxy of Monuments

Jill Schary Robinson visits “City of Immortals: Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris,” the recently published book by Carolyn Campbell.

What Makes “A People’s History”?

Hannah Zeavin examines the critical possibilities of the “people’s history.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!