A Giant Peak Called “The Doors”: A Conversation with John Densmore

James Penner interviews John Densmore, drummer for the Doors.

By James PennerJanuary 7, 2023

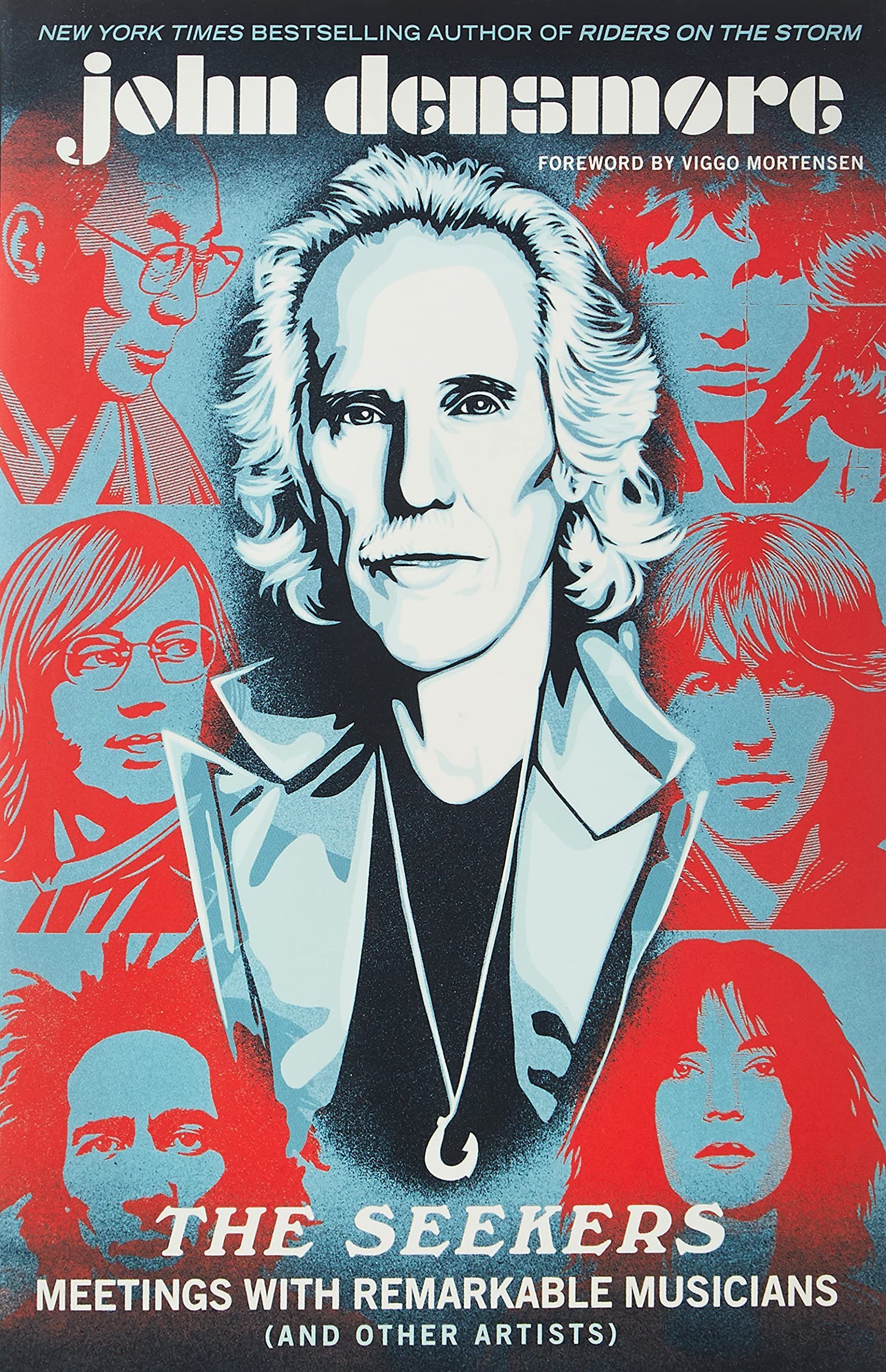

The Seekers: Meetings With Remarkable Musicians (and Other Artists) by John Densmore. Hachette Books. 240 pages.

WHEN JIM MORRISON died in a Paris bathtub in the summer of 1971, the event had a ripple effect on each remaining member of the Doors. The iconic lead singer’s untimely death meant that they would have to wrestle with the loss for the rest of their lives. Like guitarist Robby Krieger, John Densmore, the band’s mercurial percussionist, knew it was inevitable that he would miss the peak experience of playing live music for thousands of people; he also instinctively knew that rock stars in his position were uniquely susceptible to addiction and various forms of self-destruction. He thus made it his personal goal to “stay out of trouble” by pursuing various art forms throughout his life.

For Densmore, art has functioned as an antidote to self-destruction. In the decades following Morrison’s death, he has acted in plays, written memoirs, and read poetry while playing hand drums. Each new art form he has discovered has fed his psyche, staving off depression and the destructive urges that consumed Morrison and Krieger. Although Densmore still plays live music occasionally, writing has been equally important to him. In the last four decades, he has published three memoirs: Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and The Doors (1990), The Doors Unhinged: Jim Morrison’s Legacy Goes on Trial (2013), and The Seekers: Meetings with Remarkable Musicians (and Other Artists) (2020). The most recent of these works is a rhapsodic tribute to the musicians and artists who have fed his imagination and influenced him throughout his life: Elvin Jones, Van Morrison, Patti Smith, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, Gustavo Dudamel, and, of course, Ray Manzarek and Jim Morrison. Writing the chapter on Manzarek was particularly emotional for Densmore because the two band members had been adversaries in a million-dollar lawsuit over the right to use the band’s name while touring.

As I drove to Densmore’s hillside abode in the Santa Monica Mountains on a warm September morning, I wondered about his current relationship with Krieger. What did he think of Krieger’s confessional memoir Set the Night on Fire: Living, Dying, and Playing Guitar with the Doors (2021)? Did he approve? Or did the book simply open up old wounds from the trial? I also wanted to continue my own pharmacological reading of the Doors’ music (developed in my previous Los Angeles Review of Books interview with Krieger); specifically, I wanted to understand how psychedelics had influenced the band.

As I parked my car and walked to the house, I encountered a majestic set of wooden doors facing the street and knew that I had found the place. I imagined that these beautiful doors were probably what had attracted Densmore to the property when he bought it in the mid-1970s. As I walked through the portal, Densmore greeted me from his porch. A youthful 78 with a thin physique, he was wearing his gray hair long and sporting a mustache and an earring. He guided me through his art-filled house, ushering me to a sunlit breakfast nook where I could put down my books, notepads, and recording devices. Densmore, who is gregarious by nature, was eager to get started. Much like his books, he struck me as remarkably open and unguarded about his life. He was more than willing to field any question I had about any topic: his divorces, his psychedelic experiences, and his occasionally tumultuous relationships with Morrison, Manzarek, and Krieger.

¤

JAMES PENNER: Most people know you as a musician. Can you talk about John Densmore, the writer? You were the first member of the Doors to write a memoir.

JOHN DENSMORE: Yeah. And I write my books, dot dot dot.

You mean that you don’t have a co-writer or a ghostwriter?

Right. [Un]like the other guys.

How did you discover writing? And did you ever imagine that you would write three books?

So, I’m looking on the downside of a giant peak called “The Doors,” which kills people. It’s so steep. What do you do after that? Some people turn to drugs. And so, I get the idea that you zigzag, and I zigzagged into an acting class. I met Peggy Feury, a legendary acting teacher, and I sense that she’s a real mentor, you know, just like Coltrane. She’s feeding me, so this will keep me out of trouble. Plus, I am more nervous doing this. I didn’t have my drums. That’s my security blanket. In acting, your body is the instrument, you know; it’s really close to the skin. Eventually, I realized that I would like to write the words that I’m speaking, so that was my segue into writing. I started writing little articles and short pieces, and then I decided to write my autobiography, Riders on the Storm.

What’s the difference between making an album of music and writing a memoir?

Well, writing you do alone. You don’t depend on fucked-up musicians. But it’s a collaboration — making music. So, that’s fun, and you know, hanging out and bullshitting, but it’s tedious as well. Writing is also tedious, however. I remember Michael Blake. He wrote Dances with Wolves. He is an old pal of mine who passed [seven] years ago when I was just starting out. He’d say, “John, just put in an hour a day. When writing a book, don’t look at the pile of pages, just put in an hour.” And then Michael Ventura, an old friend who wrote “Letters at 3AM” [a column in LA Weekly and, later, The Austin Chronicle], had an article on writing that said, “I don’t care about talent. Can you stay in the room?” So, I would increase it to two or three hours a day for a few months. And then I’d take a break, and then I’d look at the pile, and I had 50 pages. With music, you’re in the studio and the danger is trying to find the balance between how perfectionistic you should get.

I noticed in your writing that you’re very candid. In Riders on the Storm, you don’t gloss over the uncomfortable and fraught moments in your life. When you wrote that book, were you worried that your friends or family members might be upset by what you chose to reveal?

Yeah, I was worried about revealing my brother’s suicide, and my sister was quite upset. This was a long time ago. Now, the subject is more accepted because it’s more rampant in our society via the Iraq War and kids being on their media and not connecting with anyone. So, I got letters from people saying, “You know, I felt suicidal and you’ve helped me.” I sent them to my sister and said to her, “Yeah, I’m sorry that I exposed the family secret, but there is something about celebrities discussing their problems. Like we all have to go to the bathroom and get divorced.” When I showed her the letters, she understood that it’s a form of public service. I dedicated Riders on the Storm to John Lennon for revealing his personal life in his art and music. So, there it is — I mean, John and Yoko were photographed nude.

Talk about being vulnerable.

Jesus Christ, you know, Lennon’s wonderful primal scream albums: “God is a concept by which we measure our pain […] I don’t believe in Jesus […] I just believe in […] Yoko and me.” I mean, that was as vulnerable as you can get and very inspiring.

And you’ve continued to write in this kind of confessional style?

Is that what it is? I’m still a Catholic.

Except in Catholicism, the confession is private. Your writing is public. That’s what is different about it.

Well, I mean, I’m hopefully not a blatantly confessional writer; otherwise, that’s exploitative and sensationalistic. When the moment is correct, I’m thinking, “Okay, Jim kind of committed slow suicide through alcoholism. My brother did it quickly.” So, there’s a connection here, and this should be explored. That’s when a confessional style is correct.

Riders on the Storm was written in 1990, some years ago. It’s very emotional and in some ways vulnerable. But The Doors Unhinged is a polemical book about the dangers of selling out, and it has some outrage and anger. How is The Seekers different from those two books? The Seekers feels like it comes from a different place.

I am 78, and one mellows with age, so The Seekers is a little more introspective and mellow. It’s a tip of the hat to people who fed me. It feels good to do this, and I try to figure out why they fed me. I never thought I’d write a book with my mom and Lou Reed. But, you know, she fed me. I go on and on about “the first drum beat all of us heard was in the womb, the heart, our mother’s heartbeat.” The Seekers contains an eclectic group. Ram Dass, Ravi Shankar, Patti Smith. It’s all over the map, but that’s what has fed me my whole life. I’m just voracious for whatever genre of art, the highest level of the people doing it. It’s fuel for me.

What connects all the musicians in the book?

I think it’s the love of sound. Filmmakers and painters see the world; we hear the world. That’s our main modus operandi, so that is what connects Gustavo Dudamel, Elvin Jones, and all the musicians who appear in my book.

What did you learn from acting and performing in theater?

With theater or music, being onstage is a dance. It could be a duet or an acting troupe of 10 or Gustavo Dudamel’s 80-piece L.A. Philharmonic — that’s one person, metaphorically. And the audience could be 10,000 people at Madison Square Garden, or 10 people at Beyond Baroque. When I do poetry readings — and maybe I will again when it feels better — I play hand drums when I read. And that’s the other person — that audience element. So, there’s two people. And what’s so exciting about live theater or music or whatever is that it’s instant community, which we’re all aching for during this pandemic. And you’re going to dance tonight, metaphorically. And the excitement is that you don’t know whether it’s going to be a waltz or a salsa.

So, it’s about being on stage and feeling vulnerable … and the fact that it’s unpredictable?

Well, you’re in the theater, I mean, you’re feeling the audience. You can tell if it is working or not, and it’s teaching you, and it will get real quiet — it’s a dance to pauses. Then, later on, you think, “Wow, that song really worked.” Or: “Shit, the phrasing in that section of the play felt really flat.” Therefore, the work is teaching you that you’re never done. That’s what I learned. I did a benefit at Beyond Baroque that Viggo Mortensen put on. And the people I love and respect were there — Exene [Cervenka] and John Doe — and I did my thing, and I got off on that as much as playing in front of thousands at Madison Square Garden. It’s not the size, and it’s not the goal — it’s the road … the process.

There were two Doors books that came out over the past year [2020–21]. There was The Seekers and also Robby’s book. What was your impression of Set the Night on Fire?

Talk about being vulnerable. Jesus, I had no idea Robby was so fucked up in the ’80s. Blood splattering on the bathroom walls from shooting up. Wow, that made me want to puke. God, he kept that quiet at the time.

It’s an amazing chapter. I was shocked as well.

What was your impression of his drug-use chapter [“Chasing the Dragon”]? Was that a drug warning to the reader?

I definitely think it was a really intense cautionary tale and one that was told with lots of humor. I know you have played music with Robby in recent years. Is the trial in the past? Do you feel closer to Robby now?

First, Ray got sick, and I called him and, thank God, he picked the phone up and we did talk. We talked about his illness. We didn’t talk about the lawsuit or any of that shit. And it was a shorty, but we hung up, and I felt so much better. I felt better to catch him before he checked out, so then when he did check out, I called Robby. “Hey, you know, man, death trumps everything. Do you want to jam at LACMA?” You know, just me and him. And we hadn’t played together in 10 years, or I don’t know how long. When you work on material for so long together and play it live in a few minutes, we were back. You know, it just takes a few bars.

So, have you considered writing about Robby? Because I noticed that you didn’t write a chapter about Robby in The Seekers. He obviously had a profound influence on you.

People ask me that. I don’t know. I didn’t do it consciously. I didn’t go, “Oh, fuck, Robby’s missing,” until you all started telling me. Maybe that’s The Seekers, Part Two. Writing is in my blood now, like playing music. I know I could write a really good piece on Robby. I’m getting my watering can out …

I want to talk about your experiences with psychedelics now. The Seekers is a book about gratitude as well as a book that elucidates your lifelong commitment to art and creativity. Where do psychedelics fit into the picture? Could you have written a chapter about psychedelics for The Seekers?

You’re a provocateur. I am with Ram Dass. Like him, psychedelics jump-started and opened the door to my spirituality. Or maybe it was Meher Baba, the silent guru, who said, “Now, if it’s brought you to me, now close the door.” So, in the ’60s, I was in this select little group that was experimenting with legal LSD. But there’s an incubation stage for everything creative. It is pure, and it’s really important. Margaret Mead said that it’s always a small group of people that change the world, and she didn’t mean that arrogantly.

Tell me about your first LSD trip.

I hadn’t even smoked pot, so I was a total virgin. It’s an interesting story. I was at a jam session with Bert, this sax player in a wheelchair; his improvs had a lot of anger, maybe reflecting his physical situation, but he came over one day. I was there with my best friend, Grant, who is a great keyboard player. And then Bert spreads this white powder out on the table, and I didn’t know what it was. The word “psychedelic” wasn’t in my vocabulary.

Was this around 1964?

Yeah, I think so. And Bert said, “When I take this stuff, I can walk in my mind.” Oh, my God! Wow! And so, Grant and I got into it. Grant was my roommate, and during the first five minutes or so, I’m sitting on the couch, and suddenly I get paranoid. I’m looking down into the void, the pit, you know, and then Grant starts playing the piano and laughing, and he pulls me right out of it. And then I have eight hours of seeing God in every leaf. It was really wonderful; it jump-started my spiritual life. I was raised a Catholic, but this experience had a lot more impact than the communion wafer. I took it a few more times, and then I read about Art Linkletter’s daughter falling out of a tree.* And then the word “bummer” came into my vocabulary, and I cooled it. But it’s still with me. I know there is a reality other this one right here [pointing to the table].

How were psychedelics crucial for the music of the Doors? Could the Doors have existed without psychedelics?

Psychedelics were a communal bond. They are like that. We stumbled upon each other and found out we were sharing this sacrament in our private lives. A song like “Moonlight Drive” is directly influenced [by psychedelics], and I have often described it as a psychedelic love song. You know, “Let’s swim to the moon, / Let’s climb through the tide. / Penetrate the evening that the / City sleeps to hide.” I mean, that’s pretty direct, that one. And then, Robby … well, I brought him to an audition with Ray and Jim, and I said, “Play bottleneck guitar.” And Ray and Jim went, “Wow, let’s have it on every song!” Bottleneck guitar is so liquidy and psychedelic. Could the Doors exist without LSD? I have this line, “You can’t just wear leather pants and be Jim Morrison instantly.” You have to do your homework because acid can be shattering to the nervous system. You can’t just keep taking acid. That’s not going to make you creative.

In one part of Robby’s chapter on his addiction, he mentions his realization in the late 1980s that he would never come close to creating the music that he did with the Doors, and this made him susceptible to “any chemical that could lighten the emotional load.”

That’s really good. Yeah, I mean, him more than me. I mean, I miss Jim. You know, like I said, I’ve been into his poetry. I’m getting into it further. I perform some of his poetry live, but Robby had this gorgeous baritone as a vehicle for his lyrics, and that’s gone, and I know that hurt him so badly.

So, you were different from Robby because you had other ways of coming down from the peak of the Doors? You were always acting, performing, writing, et cetera?

On a much smaller scale, obviously. But I sensed that — just be creative. I’m an artist, and no matter how big or little it is, that’ll fill you up and you won’t miss that peak as much. I mean, there was nothing like it, like Jim used to say. It was after our first few giant concerts, where the audience rioted and we had the experience of mass adulation. And Jim was like, “Well, okay, great, we did that. Now what? Let’s go to an island and start over.” And Ray was like, “No, we can’t do that!” Now, the more mature version of me thinks, “Wow, that’s noble and smart. Jim wants to keep the pure, deep creativity alive. That’s the sign of a great artist.”

¤

This interview is the second of two interviews with the remaining members of the Doors. The first interview, with Robby Krieger, appeared on December 16, 2022.

¤

¤

* In 1969, Diane Linkletter jumped out of a sixth-floor window and committed suicide. Her father Art, a radio and television personality, was convinced that LSD had led to her suicide. A close friend who spent the night talking to her, however, described her as being depressed but made no mention of drug use. Moreover, the autopsy revealed that there were no illicit substances in her body at the time of her death. The notion that she took LSD and “wanted to fly” is an urban legend that spread quickly because her father was a well-known celebrity who frequently claimed that his daughter “was murdered by the people who manufacture and sell LSD.”

LARB Contributor

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Psychedelic Genesis of the Doors: A Conversation with Robby Krieger

James Penner speaks with Robby Krieger, the guitarist for the Doors.

The Psychedelic Sacrament: A Conversation with Brian C. Muraresku

Did the ancient Greeks and early Christians use psychedelics in their ceremonies?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!