The Psychedelic Genesis of the Doors: A Conversation with Robby Krieger

James Penner speaks with Robby Krieger, the guitarist for the Doors.

By James PennerDecember 16, 2022

FOR MANY, THE DOORS are the psychedelic band par excellence, but they are also partly responsible for my first bad trip. It happened by chance, during a mushroom trip guided by a random shuffle on my iPod. When “The End” came up, I knew that it would be an intense experience. I had always assumed that the song was about the end of a relationship, or a meditation on the inevitability of death. The song famously begins with a haunting raga composed by Robby Krieger; I had always loved the interlude, but on this occasion, the raga bled into me, and before I realized what was happening, I embodied all the melancholy emotions of the song. Before long, I was on the floor in the fetal position. After the song was over, I remembered that it’s desirable to change your activity when you are in the middle of a bad trip, so I decided to take a bath. As the hot, cleansing water poured over me, the painful residue of the experience seemed to evaporate in the bubbles that filled the tub. All in all, I guess the bad part of the trip lasted some 45 minutes, but as with all bad trips, it felt like an eternity.

A few days after my visceral experience with “The End,” I realized that some bad trips are necessary because they purge the negative emotions lodged in the psyche. I also had immense respect for the Doors and their capacity to evoke such powerful emotions. During my trip, I was a conduit for the raw power of the band’s music: “The End” and its raga interlude — dreamlike and enchanting — conveyed an unconscious language that was at once foreign and familiar to me. I marveled at the song’s artistry and its ability to transform my entire emotional state. I had never had a musical experience like this one before.

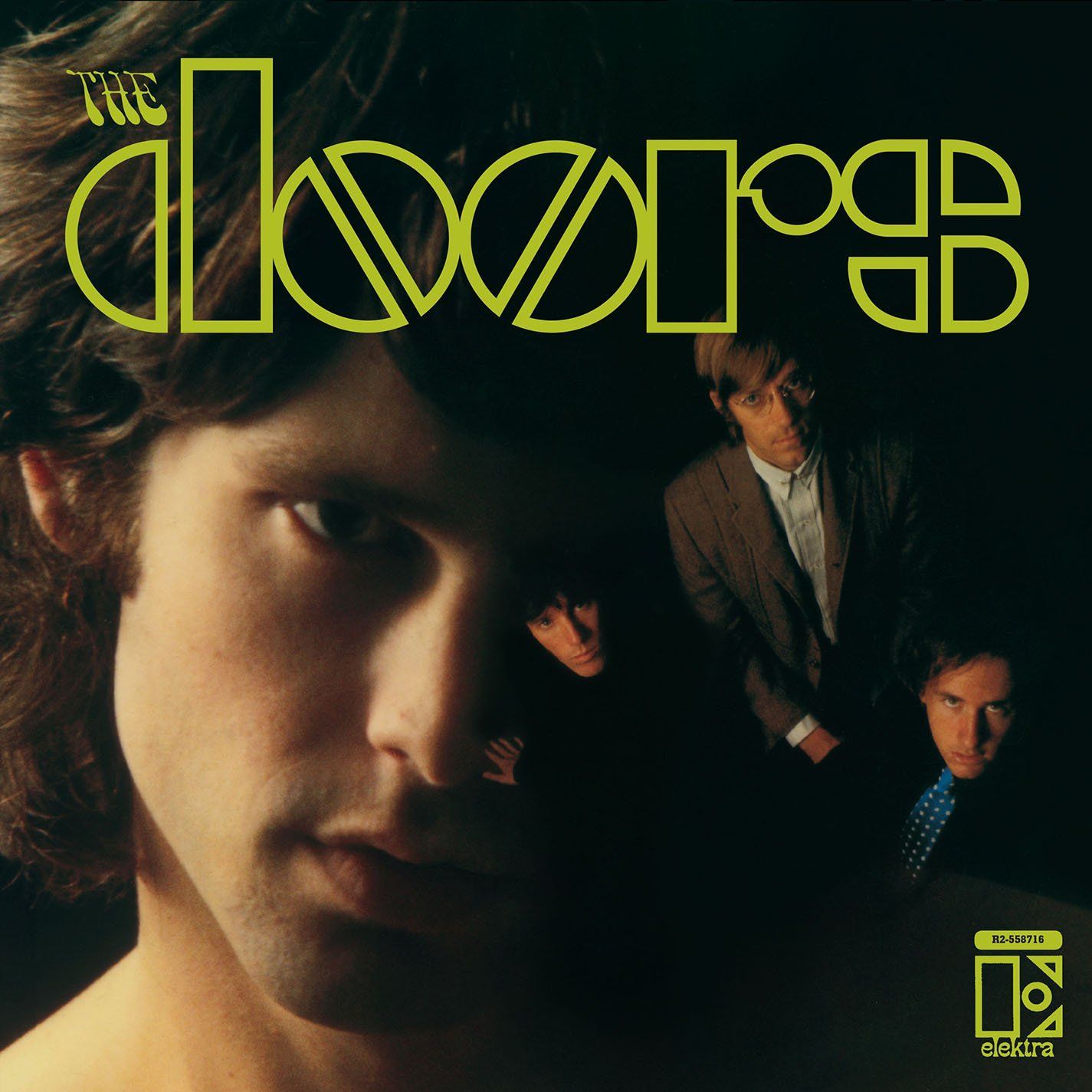

When I arranged to interview Robby Krieger for Los Angeles Review of Books, I knew it would be a special occasion because I would be meeting the man who had composed the raga for “The End” some 50 years ago. In a strange way, Krieger and I had a musical bond: I was interviewing him some 15 years after my intensely visceral experience with “The End.” During my interview, I wanted to understand how exactly psychedelics had influenced the musical DNA of the Doors, so I decided that my approach would involve a pharmacological reading of the band. I would avoid the standard geek questions (which guitar did you play when you wrote “Light My Fire”?) in favor of questions about psychedelic drugs and their effects. To what extent did various chemicals — cannabis, LSD, psilocybin, alcohol, etc. — influence the music of the Doors and the overall trajectory of the band? As has been well established by music critics, the early albums were heavily influenced by LSD and often contain lyrics that valorize the experience of expanded consciousness — “Break On Through (To the Other Side),” for example. But I also noted a distinct chemical shift in the blues-rock trajectory of their last two albums, Morrison Hotel (1970) and L.A. Woman (1971); Jim Morrison’s frayed vocals reveal the lead singer’s unmistakable devotion to alcohol.

To prepare for my interview, I read Krieger’s recently published memoir Set the Night on Fire: Living, Dying, and Playing Guitar with the Doors (2021) with great interest. Until that book appeared, Krieger was the only member of the Doors who had not written about his experiences in the band; the acclaimed guitarist was reluctant to publish the memoir in the 1990s because he feared that it might cause further division within the surviving group. Drummer John Densmore’s Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and the Doors (1990) had deeply angered the band’s keyboard player, Ray Manzarek, who was offended at being accused of recycling the myth that Morrison might still be alive. Manzarek returned the favor, skewering Densmore in his own memoir, Light My Fire: My Life with the Doors (1997). By contrast, Krieger’s Set the Night on Fire does not attempt to settle scores, but it does offer some provocative revelations that might surprise many fans and music critics.

Unlike Manzarek’s somewhat hyperbolic approach to the band’s history in Light My Fire, Krieger’s memoir has a distinctly anti-mythic thrust. For example, he is willing to concede that the Doors were never fired from the Whisky a Go Go when Morrison sang the profane Oedipal verses from “The End” (“Father, I want to kill you / Mother, I want to …”). Krieger is similarly candid about a wide range of topics: his experiences with heroin and cocaine (speedballs), the mental illness within his family history, and the ubiquity of sexually transmitted diseases during the 1960s. Set the Night on Fire reveals that drugs, for better or worse, played a crucial role in the guitarist’s creative development and his personal life. His memoir’s candor is matched by its generosity as it attempts to repair the remaining schisms within the Doors and also heal the wounds that linger from his personal struggles with addiction. As rock memoirs go, Set the Night on Fire is certainly a compelling one; Krieger and his talented co-writer, Jeff Alulis, have created a nonlinear narrative that sheds light on the epiphanic moments from the guitarist’s intense and topsy-turvy life.

Krieger, who turned 76 this year, still tours and frequently plays music with two bands, the Robby Krieger Band and Robby Krieger & the Soul Savages. When the guitarist met me at his hillside home in Benedict Canyon, we exchanged greetings before he ushered me to into his musical inner sanctum. I was amazed to see him dash up the stairs to his studio; it is clear that playing music has sustained his youthful energy. In his musical hideaway, acoustic and electric guitars were everywhere, though he graciously removed a few from his couch so that I could sit down.

¤

JAMES PENNER: One of the things that is refreshing about your memoir is its remarkable candor — you definitely don’t gloss over the more difficult and fraught moments of your life. Was this on purpose?

ROBBY KRIEGER: I think so. When I read Keith Richards’s Life [2010], I noticed that he kind of glosses over his drug addiction and his use of heroin. I didn’t want to make this mistake. People want to know about that stuff firsthand rather than hear about it from some unknown source.

Along those lines, your memoir often reads like an extended confession. Were you worried that some of your friends or family members might be upset by what you chose to reveal?

Yeah, I worried about it a little bit. But at my age, you don’t really care about that. This was another good reason to wait and not write my memoir in the 1990s. Waiting until your seventies gives you the freedom to say everything.

The other thing that was really interesting about your memoir was its anti-mythic thrust. I noticed that you wanted to deflate certain myths about the Doors, especially the ones propagated by Oliver Stone’s movie (The Doors, 1991) and Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman’s book, No One Here Gets Out Alive (1980). Was this a conscious choice?

Yeah, because it’s so easy to just believe that stuff. And, you know, even I start believing the myths. I mean, the movie — I just saw it again the other night, and there’s so many little parts that seem more and more true. And even I started thinking that they might have happened because it’s 50 years ago. You forget about many details from your life, but in a movie it’s there forever. And people all over the place see it every day. It creates new myths, and some of the myths are really seductive.

So right from the beginning of the memoir, you wanted to deflate the myths in Stone’s movie, as well as Ray’s memoir, Light My Fire?

To me, the truth is more interesting than fiction.

In one of my favorite passages, you openly admit that your memory is flawed and that your “brain is old, and always getting older.” So, how reliable is your memory of the past?

Well, I think I remember the past more than I do yesterday. My memory is still pretty good, but I do forget a lot of stuff.

For example, when everybody thinks that the Doors got fired from the Whisky because of Jim singing the profane lyrics from “The End,” you point out in your memoir that that’s not what happened. You suggest that Stone’s movie created this myth. How do you know that your memory of this event is reliable?

I mean, I could be wrong, you know, but I think I would have remembered if the owner said, “You guys are fired!” Playing “The End” wasn’t that big of a deal. When we did the song, it was kind of weird because we started the set with “The End,” which we never had done before. So I think people were kind of interested in that because a lot of those people were there every night because we were the house band for the Whisky. And when Jim said, “Father, I want to kill you. Mother, I want to …” — to me, it was just poetry. It wasn’t like everybody at the Whisky was shocked and slack-jawed and just couldn’t believe what they were hearing. That didn’t happen. I am sure that the owners of the Whisky didn’t give a shit.

There was one subject that you didn’t talk about too much in your memoir: the significance of Los Angeles. I found it really interesting that Los Angeles was so important to your life. I’m just thinking about all the places you’ve lived — Pacific Palisades, Venice, Laurel Canyon, Malibu, Topanga Beach, and Benedict Canyon. Can you talk about your relationship with the city and how it influenced the trajectory of your life and the music of the Doors?

Well, that’s a good question. If I had grown up somewhere else, would I ever have been the same? I doubt it. The whole L.A. scene was so important to me. Guys like Jan and Dean — they went to my high school. I really liked their stuff compared to a lot of other music at the time. And the whole surf scene was also really cool.

What makes the Doors a West Coast band and an L.A. band?

Well, me and John. The other guys weren’t from Los Angeles. Jim was a Navy brat who grew up everywhere and Ray was from Chicago, which was a good thing because he brought the blues into the band. He had an amazing record collection at his house. That was where we came up with the idea of doing Kurt Weill’s “Alabama Song”; I mean, none of us had ever heard of Kurt Weill. And there was being in Hollywood and the whole Hollywood scene, especially the Capitol Records Building. One of the coolest parts about Los Angeles was the record business. Even Elektra was here. They were actually based in New York when we started, and then, right after we hit it big, they moved out here because they saw the writing on the wall.

I think another key element of the Doors has got to be psychedelics. In your memoir, you talk about how doing psychedelics was one of the pivotal moments in your life. Why were psychedelics so important to you?

Sure, I think psychedelics just showed me that there was something else out there. There were other possibilities than what I had previously thought. It opens your mind up to the possibility of a religious experience. Before I did psychedelics, I didn’t believe in the religious experience because my parents were Jewish, but they were trying to pass for white. My family never went to temple. They just didn’t believe in it, probably because their parents were trying to push it on to them when they were growing up.

So psychedelics kind of opened up this whole new way of looking at life and existence?

I began to believe that there’s something else going on and you don’t know what it is. That’s why I liked Bob Dylan so much. He was able to tap into that. He was Jewish too. I’ll bet you psychedelics probably did the same thing for him. When I listened to his music, I could tell which songs he was writing on acid.

Really. Which songs?

The early stuff: “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Songs like that. You can just tell that he was tripping. Take acid and check those songs out. In “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” the words really don’t mean anything. It’s just that they go together somehow, and they give you these powerful images. And that’s exactly what happens when you take psychedelics. And Jim [Morrison] was able to write stuff when he was on acid. I couldn’t do it, but he could. Jim was at his best with psychedelics. The problem was that he would do what he always did — overdo everything. He took way too much acid and then it made him want to come back down. I guess that’s when he started drinking — drinking alcohol was his ruination.

When I’ve listened to music while I’m tripping, I hear the music so differently and on a much higher level. I feel like I’ve had wax in my ears for my whole life, and when I’m tripping, suddenly the wax is gone and I can hear all these things that I normally don’t hear. Did you ever have that experience?

Sure. And you don’t really know whether it’s something in the music that you’ve been missing or whether it’s just you adding something else to the music. I think it’s both. I used to listen to Paul Butterfield’s first album. I heard it before and liked it, but when I heard it on acid, it was so amazing and different. And the same thing happened when I listened to Bob Dylan’s music.

Would you say that psychedelics were crucial for the Doors?

It’s true. Who knows whether we would have come together if it hadn’t been for psychedelics? In 1964 or 1965, I was getting kind of tired of psychedelics because we ended up doing them every weekend. It was like a ritual. This period was before the Doors. And the same thing happened to Ray, except it was even worse. He had started having bad trips, and that’s why he decided to try Transcendental Meditation. And that’s kind of why I had to try TM as well. People were saying, “Oh, TM is going to be the next big thing after LSD.” That’s when I got John [Densmore] to come with me to meet the Maharishi [Mahesh Yogi].

So your interest in Transcendental Meditation was a way of cutting down on acid?

Exactly. Meditation was a way to alter your consciousness and still be able to transcend reality, but for me it didn’t really work because it took too long.

Meditation is more difficult. It is hard work.

You might have to wait 80 years for it to work. So, you are still taking psychedelics?

Yeah, I have had some wonderful experiences. I mean, I don’t do it all the time, but I’ve had really good trips for the most part.

That’s great. For me, I don’t take LSD anymore.

Was it in 1965 when you stopped?

No. I’d taken it off and on for, you know, another 20 years or so, but I finally gave it up.

And why is that?

I don’t know. It just didn’t seem as good. It’s probably because you couldn’t get the real thing anymore. You know, we used to get Sandoz LSD in the early ’60s. And so I would tend to just do peyote and mushrooms, or morning glory seeds. I have never had a bad trip on psychedelics. The only bad trips that I have had have been from smoking too much weed or taking edibles. They made me paranoid.

So if you’ve had really good trips and you’ve never had a bad trip, why give up psychedelics?

It just didn’t seem like it was “real” anymore. You know once you’ve been to that place that you can never really get back to the same place, and you’re always trying. It’s like when you reach a state of enlightenment.

Do you mean samadhi?

Yes, like the first time you took acid, or if you’re meditating and you get the white light, or whatever — you know — then that’s it. You’ve done it. And no amount of doing it again is ever going to get you back to that state. You get from that place of not knowing to the place of knowing.

I also wanted to discuss your experience with opioids. I have to say, your “Chasing the Dragon” chapter, which describes your struggles with addiction, was really powerful. I mean, you go from weed to LSD to cocaine, heroin, and, eventually, speedballs. How do you explain that trajectory? It’s like you are a poster boy for the gateway theory of drug addiction.

Yeah, it’s funny because I never thought that I would be the one to get hooked on hard drugs. I never even drank or smoked cigarettes. And after seeing my parents — my mom was hooked on codeine — and then Jim and Pam Courson. I never saw myself doing it, but even then — in the back of my mind, I always wondered, why did all of my heroes do heroin? Coltrane and Miles Davis. Who knows, if they hadn’t done it, they might be still doing great things. It took me too long to figure that out.

You had that one passage where you talk about your addiction. Perhaps I should just read it:

I loved playing and collaborating with new musicians in the seventies and eighties, but it was repeatedly made obvious that I would never achieve what we did with the Doors. Accepting that fact drove me deeper and deeper into an unacknowledged depression and left me wide open to any chemical that could lighten the emotional load.

Does this seem like a good explanation for your addiction?

I didn’t think so at the time, but looking back, I think that this could be one of the reasons. I mean, how do you top something like the Doors? Do you know what’s the worst part of this? My best song ever — “Light My Fire” — was the first one I wrote.

That’s one way of looking at it, but I wouldn’t look at it like that.

I don’t really look at it like that, but I don’t know, there’s got to be a reason for my addiction. Maybe I was too sensitive. I think, in Jim’s case especially, that’s one of the reasons why he became addicted to alcohol. Jim just was so vulnerable to everyday stuff that most people would just shrug off, so that made him open to escaping. And these geniuses like Davis and Coltrane — both of those guys tried heroin. It just makes you feel like you don’t notice anything.

How did you arrive at speedballs? A good friend of mine actually really got into them as well.

When people start doing heroin, it kind of makes you too sleepy. And then you want to go the other way. What’s the other way? Cocaine, because it wakes you up. But those two together make you feel really good. Too good. In fact, it’s so good that you can’t stop doing it. You buy some and it’ll be gone right away because you can’t wait to start doing them. You don’t save any for the next day. It’s like a double addiction. And doing it at the same time multiplies the effect.

How is it that you were able to get off it without going to rehab or Narcotics Anonymous?

It was because they did an intervention. John [Densmore] did it. It was his idea. And it just makes you really embarrassed. You can’t believe that you did such a stupid thing.

You don’t seem embarrassed by it now. You seem to be okay with writing about it.

I was embarrassed at the time, some 30 years ago. But yeah, the interventions were just getting started at that time.

I’m really glad you included that chapter in your memoir. It’s a really powerful statement about addiction.

I hope it will stop people from going down that road. However, the worst thing is that my chapter might give some people the idea to try speedballs.

You can never be sure how people will read a text — or misread it.

Hopefully, people will learn that it’s not the right thing to do.

My final question is about what makes the music of the Doors so unique. The interesting thing about the band is that each of you came from the margins, the peripheries of rock music. You were into flamenco, Indian music, and John Coltrane. You thought rock and roll was boring because it only used three chords. Ray was a classically trained pianist who was really into the blues. John was a jazz drummer who idolized Elvin Jones. And Jim wasn’t a musician at all; he was a poet. How on earth did the four of you end up creating rock and roll?

Why did we want to play rock in the first place when none of us were rockers? I think it’s a good question. I think because the Beatles had just come out with some really innovative records. And the Rolling Stones. Some of the English bands were just getting started, so I think rock started to have a more experimental sound. Had it been two years earlier, maybe we never would have been in a rock band. The music of the Doors, from the start, was a step up from the early rock and roll that existed in the ’60s. It was exciting to try to evolve the music — to take out the boring parts and try to put in something new.

¤

This interview is the first of two interviews with the remaining members of the Doors. The interview with John Densmore will appear on January 6, 2023.

¤

LARB Contributor

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Psychedelic Sacrament: A Conversation with Brian C. Muraresku

Did the ancient Greeks and early Christians use psychedelics in their ceremonies?

Toward a Saner Psychedelia

Ido Hartogsohn’s new book explores the impact of LSD on postwar American society and culture.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!