A Clamor of Beings: Two New Translations of Felix Salten’s “Bambi”

Maddie Crum reviews two new editions of Felix Salten’s classic novel “Bambi.”

By Madeleine CrumNovember 3, 2022

Bambi by Felix Salten. NYRB Classics. 152 pages.

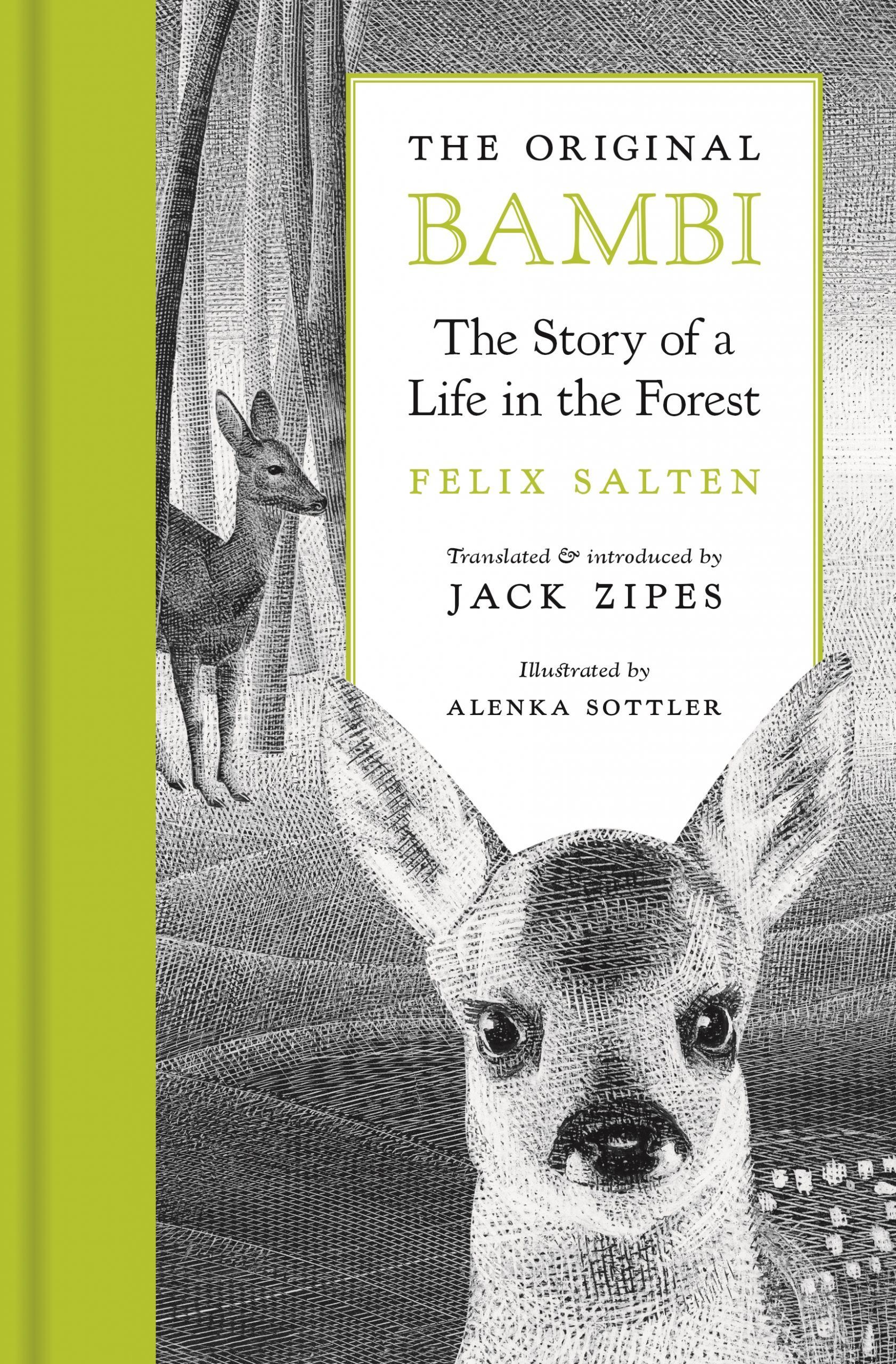

The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest by Felix Salten. Princeton University Press. 192 pages.

IN FELIX SALTEN’S NOVEL Bambi — published in Berlin in 1923 and cutesified by Disney in 1942, around the same time that its author, whose work had by then been banned by the Nazis, fled Austria to Zurich with his family — there isn’t a single woodland creature with glistening eyes. No long lashes, either. The natural world is often portrayed frankly, in a tone of reportage so detailed it seems to reveal an obsession. “Blackthorn bushes and hazelnut, dogwood, and young elder trees grew all around,” Salten writes of the titular roe deer’s stretch of woods. “Tall maples, beeches, and oaks formed a green roof over the thicket, and ferns, vetches, and sage sprang from the firm dark soil.”

Salten was a journalist, a theater critic, a short story writer, and, after publishing Bambi, the author of several other novels told from animals’ points of view, including Perri: The Youth of a Squirrel (1938), Bambi’s Children: The Story of a Forest Family (1939), and Renni the Rescuer: A Dog of the Battlefield (1940). He was also a hunter, criticized for his pastime by his contemporaries. But, as he wrote, “Bambi would never have come into being if I had never aimed my bullet at the head of a roebuck or elk.”

In Bambi, Salten’s reportage often turns toward scenes of violence. A “dying pheasant” convulses in the snow after humans raid the forest and meadow. The bird has “a twisted neck, its wings flapping feebly.” A roe deer, one Bambi hadn’t met before, mutters, “I can’t walk at the moment,” and “[i]n the middle of talking she slumped to one side and was dead.” This carnage was scrubbed from the cartoon adaptation, of course, but the novel’s most dramatic moment, the sudden death of Bambi’s mother at the hands — or barrels, rather — of anonymous hunters, was kept intact, to many viewers’ dismay.

According to Jack Zipes, whose research centers on folk and fairy tales and who translated another new edition of Bambi published in February by Princeton University Press, a lot else was lost in Disney’s translation, including the nuances of Viennese society and the power structures that might have occupied Salten — specifically, the anti-Semitism he faced all his life, leading him to change his name from Siegmund Salzmann. Zipes’s translation of Bambi inspired a flurry of critical interest: Publishers Weekly wrote of the story’s “dark origins,” and The Guardian called it a “dark parable.” Bambi was an allegory prefiguring the Holocaust; it was, though a classic bildungsroman, not a sentimental story for children. Crucially, Zipes said on his publisher’s podcast, it was not an environmental novel.

In September, NYRB Classics released its own version of Bambi, translated by Damion Searls with an afterword by Paul Reitter, author of Bambi’s Jewish Roots and Other Essays on German-Jewish Culture (2015). Like Zipes, Reitter pays attention to Salten’s interest in the psychological effects of oppression, but he’s less dismissive of Bambi’s distinction as an early work of environmental fiction. According to Reitter, Salten’s “primary political intention in Bambi and elsewhere was to ‘humanize animals’ […] so that humans wouldn’t treat them like beasts.”

Thus, in these coincident rereleases of a misunderstood classic, two perspectives have surfaced: Bambi is either an allegory for human oppression and suffering, or it is a critique of humankind’s assault on nature. But why not both? Zipes’s take that Bambi is allegorical and therefore not a work of ecofiction is an either-or fallacy that might be a consequence of academic siloing, but it’s also revealing of common attitudes toward art centered on nature: it’s sentimental, kids’ stuff, full of glistening eyes, flowers, and the moon, told in a high, musical pitch.

This is not a baseless attitude. You don’t need to look beyond a bookstore’s bestseller rack — or your own Instagram feed — to know that nature, which needs no language to inspire awe, inspires instead some of the vaguest, rosiest-colored art. And the English-language roots of what’s now called ecofiction see human beings escaping merrily to nature, shepherd’s crook in hand, in order to live more simply, retreating from the sad, smoggy city life — never mind the effects that smog may have on the green backdrop.

By the 1970s, works in the then-flourishing genre shifted focus, giving at least equal attention to human society and to nature beyond its effect on human beings, exploring lush overgrowth that was weedy and not always accommodating. Outlining his criteria for ecofiction, Lawrence Buell concludes that “[h]uman accountability to the environment is part of the text’s ethical orientation” and “the nonhuman environment is present not merely as a framing device.”

By these measures, Bambi is absolutely an environmental novel. As in the movie, humankind — called simply “Him” by the story’s fauna, who speak the name in murmurs — is the villain. The second criterion is trickier. After all, aren’t all attempts at understanding the psychology and complex behavior of plants and animals limited, if not to simple framing devices, then at least to voyeuristic imaginings? Still, Salten attempts to write about deer as they relate to other deer — and to owls, warblers, rabbits, and falcons, a clamor of beings. Falcons “screec[h], sharp and joyous: Yayaya!”; trees “groan” and “sigh”; autumn leaves discuss their mortality before falling to the forest floor.

Humans can’t write about nature without leaving tracks; still, Salten, a hunter, listened closely to forest sounds. The world of Bambi is alive with Viennese chatter and warblers’ cries, allegory and realism. Glee at the sight of an open meadow — a kind of natural commons where animals romp, away from their lonely and sequestered thickets — serves as a hopeful symbol. What might life be like for Salten and other Jews if they were free from persecution? But the meadow is also just a meadow, as the toad in Marianne Moore’s imaginary garden is also a toad. For Bambi, the meadow is a site of rollicking, tumbling; the novel’s narrator, on the other hand, is measured in his description, ending an otherwise cheerful scene bluntly: “That was the meadow.”

This bluntness foreshadows the meadow as a site of violence and youthful joy curtailed. It’s Him who kills Bambi’s mother in a chapter that ends just as bluntly: “Bambi never saw his mother again.” The following scene flashes forward; Bambi has grown antlers and is now ornery, “beating his new crown against the wood” of a hazelbush. “[H]e needed to do it,” Salten writes. His grief rendering him antisocial, Bambi excuses himself rudely from a chat with an owl who mentions his mother in passing. Now, his only close relation is the Old Stag, an intimidating figure he seeks but rarely encounters, and who may or may not be his father. With each run-in, the Old Stag warns Bambi: “If you want to protect yourself, want to understand life, want to attain wisdom, you must stay alone!”

Bambi’s arc leads him toward the Old Stag’s isolation and stoicism; here, Zipes and Reitter again offer different interpretations. Zipes regards the novel’s ending as a tragedy: although Bambi hasn’t yet been killed by Him, he’s conscripted to a totally self-protective existence, living only to survive, as a member of a persecuted group. Reitter, meanwhile, applies a Freudian lens: Bambi separates from his mother and hopes to become his estranged father. “In this context,” he writes, “solitude is a paradoxical means of belonging.” The work itself seems to regard Bambi’s solitude as melancholic, if also at times peaceful. Salten writes: “Bambi was alone. He walked to where the stream flowed quietly between the reeds and willows on its banks.”

Bambi’s response to human violence is interpretable, but the forest creatures’ collective response to Him provides one of the book’s most overtly allegorical scenes, a proto–Animal Farm perhaps, a wild town hall. Bambi’s cousin Gobo is taken captive by Him and returns to the forest newly fattened and accustomed to comfort. “Sad,” the Old Stag laments, but Gobo believes men to be generous. Other deer insist that reconciliation is necessary; still others claim it’s impossible.

When a man arrives on the scene, he’s a shadowy aberration. Through Bambi’s eyes, he is magical and grotesque, like a Romantic rendering of nature, eliciting fear and wonder. “For a long time the shape doesn’t move,” Salten writes. “Then it sticks out a leg, a leg that’s on top, near the face, which Bambi hadn’t noticed was there at all.” And later, “There He was, coming out from the bushes, there, and there, and there. He appeared everywhere, lashing out in all directions, thrashing the shrubs, drumming on the tree trunks.”

As readers who are also, of course, human beings, we find ourselves made weird, monstrous, even implicated. The relationship between humankind and nature is unique in the literature of oppression. Unlike, say, a novel by a colonizer written from the imagined point-of-view of the colonized, there is no (as yet known) possibility that a roe deer will write something like Bambi; there’s only the determination to use fiction to try and see what he sees. And Salten does this, with a clear purpose: to write us as we have written animals, to exalt Him, a shadowy, godlike force, as something to be feared, like fate. And also, to reduce Him: humans are reduced to a mere pronoun, almost totally stripped of description (though in Searls’s translation, he’s called “pale” more than once). He’s flattened into a symbol, and this flattening is so total that it can only be deliberate. It’s Bambi’s world — his hunger, his fear, his coming of age, his place amid the thicket and beside the stream, his annoyance with the twittering of warblers — that truly matters.

Salten’s use of animal characters obviously tells a story more relevant to humans than to nonhumans. But that doesn’t mean human oppression is its only message. The density of Salten’s natural descriptions, the reportorial voice in which he delivers them, and his careful movements between stylized, allegorical scenes and stark realism suggest that his intentions are multiple: to peer at the unadulterated meadow as from a hunting blind; to step away from the blind, weapon in hand, and see how our armed presence disturbs the balance of things; and to suggest that this imbalance exists not only in the meadow but also, for example, in Vienna in 1923.

To choose only one of these interpretations is to ignore the mutuality of our human suffering and nature’s suffering, which is no longer only a poetic platitude but an urgent fact. How could we have lost sight of that mutuality? In one of the most affecting scenes involving Him, Salten points to a culprit. Bambi and the Old Stag dodge a trap, which confounds Bambi. The Old Stag explains that the trap is Him, but He Himself isn’t currently in the forest. “And still, it’s Him!” Bambi cries, shaking his head. Humans are alienated from the task of hunting, relying on machines, which arouses in Bambi wonder, fear, and pity.

Returning to Bambi nearly a century after it was published is an opportunity to attune ourselves to its cacophony of sounds, its ripples of gossip, its characters’ headbutting. The book is a rich and busy ecosystem — much like a Viennese café.

¤

LARB Contributor

Madeleine Crum is a writer in Brooklyn. Recently, she has written for Literary Hub, The Scofield, Vulture, and HuffPost, where she was a books editor and culture reporter. She is from Texas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Beyond Talking Bunnies: On Victor Menza’s “The Rabbit Between Us”

Katja M. Guenther reviews Victor Menza’s posthumous book on the rabbit as racially charged American symbol.

Generating Hope: Jack Zipes Republishes Anti-Fascist Children’s Book from the Early 20th Century

Jonathan Alexander talks with Jack Zipes about “Yussuf the Ostrich” and “Keedle, the Great.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!