A Chinese Classic Journeys to the West: Julia Lovell’s Translation of “Monkey King”

Minjie Chen on “Monkey King: Journey to the West” by Wu Cheng’en, translated by Julia Lovell.

By Minjie ChenOctober 5, 2021

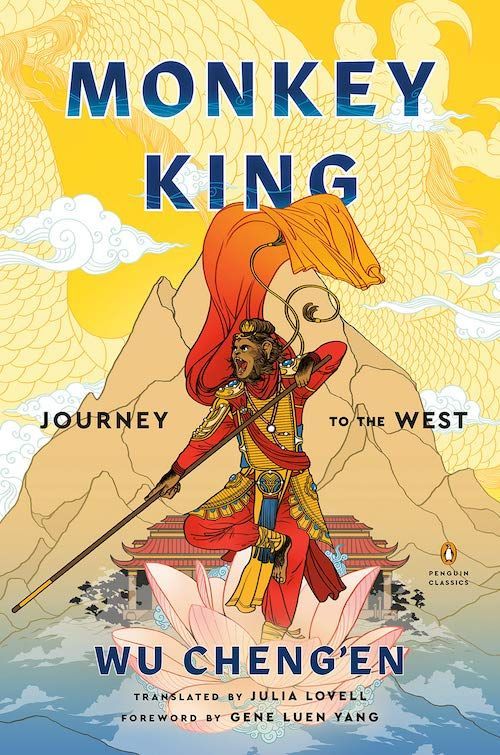

Monkey King: Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en. Penguin Classics. 384 pages.

EXCEPT FOR THE one error I spotted on its cover, Julia Lovell’s new translation of Monkey King: Journey to the West is the best English edition of the classic Chinese fantasy novel, Xi You Ji (literally “west journey record”), I have ever read. If you wish to understand why Monkey King has been a fixture in Chinese popular culture for no fewer than five centuries, then look no further. Pick up this edition and you will join the 1.5 billion people who, to paraphrase Neil Gaiman’s comment on the tale, share in their DNA an intimate knowledge of the havoc-wreaking Monkey’s herculean journey westward to find a special collection of Buddhist sutras in India.

Xuanzang, a monk of the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), made a 16-year pilgrimage to India in the seventh century, before bringing back Buddhist scriptures and devoting the rest of his life translating those Sanskrit texts into Chinese. His extraordinary trip inspired numerous legends in oral storytelling and folk entertainment. By the time a 100-chapter version of Journey to the West was compiled and published in 1592, there had been little semblance between Xuanzang’s original account of his travels and the fantasy novel. The latter features a Buddhist monk named Tripitaka, his three hideous-looking disciples, and an enormous cast of deities, immortals, demons, and spirits. At the center of the saga is a magical monkey named Sun Wukong — frequently referred to as Monkey King — who is the most powerful of the disciples.

Monkey has no parents. He is born from a stone egg, which has been fertilized and nourished by the essences of Heaven and Earth since the Creation. (Chinese parents love to steal this plot and appropriate it as an answer to the dreaded question from their toddlers, “Where did I come from?” thus contributing to a widespread misunderstanding about human reproduction among Chinese children.) After attending a Taoist school, Monkey masters the supernatural powers of flying on clouds and cloning himself from body hair. He is capable of 72 self-transformations, which means Monkey can turn into another being (without the help of the Polyjuice Potion), any creature (sans the restrictions imposed on Animagi), or a still object.

For his outrageous audacity to rebel against the established deities, Monkey is imprisoned by the Buddha under a mountain for 500 years until an opportunity for redemption finally comes. He is to serve as a disciple and protector of Tripitaka, who is ordained to undergo 81 ordeals before he can be granted sutras from the Buddha’s monastery library in Western Heaven. As it turns out, the monk and his three disciples — Monkey, Pigsy, and Sandy — had all fallen from grace in their current or past lives and received this second chance.

Journey to the West is one of those classics you can read and reread at any age. Each time it reveals something new to you. Child readers easily relate to the flaws and weaknesses of Monkey and his fellow disciples, who are at times impatient, reckless, and vain — they are clearly not the type to ace the famous “marshmallow test” designed to assess one’s ability to delay gratification. As I grow older, I am drawn to Journey to the West for additional reasons. Tripitaka’s predestined 81 calamities put the challenges and setbacks of my own into perspective. Children are captivated by Monkey’s superpower, but the bruises inflicted by life have taught me to recognize where his true strength lies — in his self-acceptance in low moments (or low centuries) and humility to persevere with his second chance. At whichever age you open the book, however, you are sure to chuckle over something funny, be it slapstick humor or subtle mockery.

This translation has earned my rating as the best English edition of the work because of the ways Julia Lovell reshaped and enhanced the text. First, with unapologetic decisiveness, Lovell cut and condensed descriptive passages and poems that contribute little to the pace of storytelling. Take the opening passage for example. Lovell’s version summarizes the entire first page of Chinese verse and prose in one brief paragraph in English and moves briskly to the more significant detail about the fertilized stone egg. My copy of Anthony C. Yu’s The Monkey and the Monk (2006) shows few signs of wear, even though this edition’s faithfulness to the original Chinese means it is good for English language learning. Its more direct translations lead to meandering theoretical exposition of the history of the universe that opens the first chapter. On the other hand, Lovell knows what is best to retain. Later in the story, when a hungry Pigsy is rebuked by Monkey for being a complainer, Pigsy shoots back, “We can’t all drink wind and burp mist like you.” Impressed by the expressiveness of Pigsy’s retort, I checked the 1954 Chinese edition, on which Lovell’s translation is based, and was somewhat surprised that it is directly lifted off the original text. When the pithy dialogue was buried in the lengthier original Chinese version, however, I never for once noticed it.

Second, Lovell’s selection of episodes from the Chinese version is satisfying. Lovell’s Monkey King is about a quarter of the length of the original. Of the 81 calamities, the episodes selected for translation are representative of the diverse nature of the ordeals. Tripitaka is a magnet for peril by virtue of being coveted by demons, who believe a bite of the monk would give them immortality. In one of the most imaginative episodes, the pilgrims travel to the Land of Women, are impregnated by drinking from the local river, and forced to seek emergency abortions. I do wish, though, that Lovell had not eliminated one of the earlier funny chapters in which Monkey and Pigsy succumb to gastronomic lure, invite themselves to taste the precious immortal ginseng fruit, and get into big trouble — Monkey has to exhaust his reservoir of superpowers and deity networks to reverse the rapidly escalating damage and to appease the wrathful owner of the magic tree.

Monkey’s trajectory of maturation is preserved — or perhaps is even more prominent — because of the careful selective compression of stories. He begins by pursuing personal gratification but learns to use his superpower to amend his own wrongdoings and to save lives. The pilgrims, bickering and betraying like rivalrous siblings, are not exactly model team players at the onset of the journey. The team shows increasing mutual trust, gratitude, and understanding as members survive one mishap after another. In the latter segments of their voyage, Monkey, who is short of confessing ADHD, and Tripitaka, who knows no magic, play off each other’s strengths to win a high-stakes meditation contest and to outmaneuver three cunning animal spirits.

Third, Monkey King accentuates one of the major appeals of the novel — its humor — with embellishments made by the translator in three main ways: dialogue, the culture of the immortal society, and the technicality of magic. Monkey is nothing without his complete disregard for formality, even (or especially) as he interacts with those perching at the top of the deities’ hierarchical system. He evokes both childish innocence and rebellious boldness. The English edition takes this characteristic and runs with it, tweaking a word choice here and perfecting a repartee there, in line with the lighthearted tone of the original. I should mention also that Lovell excels at spicing up the insults exchanged between Monkey and his enemies. One of the spirits sent to subdue Monkey threatens his monkey kingdom, “The merest whisper of resistance and we'll turn the lot of you into baboon butter” — you will not find “baboon butter” in the original version.

Another source of humor in the book is how the Heavenly administration system that governs immortals is a close mimicry of the bureaucracy of the mortal world. In Monkey King, their comic resemblance is further amplified by modernized vocabulary not found in the original. When Monkey is offered his first government post in Heaven, he meets a deity from “Immortal Resources” giving the Jade Emperor an update on vacancies.

Lovell has also strengthened the internal logic and technical rigor of the magic. Flying on clouds is a major magic skill of the immortals. Monkey King is more articulate about the magical mechanisms of the cloud-based transportation system, one that is responsive to the take-off posture of the rider and the speed of the gale the immortal is able to summon.

Because it is a story rooted in folk culture, Journey to the West has never ceased transforming. As it was performed by professional storytellers in teahouses, disseminated via woodblock printed paperbacks, and adapted into shadow plays, Peking operas, animated films, and pop-up picture books, generations of storytellers have built on others’ work, thus enriching the plot and reimagining the divine world. With its attentive reworkings of language and details, Monkey King has joined this time-honored tradition of reshaping and refreshing the old tale for a new audience.

This leads me to the “one error” I referred to on the front cover. I take issue with the wording “translated” by Julia Lovell. The verb does not nearly capture the amount of editing, retelling, and enhancement she has done to the text. Lovell is more of a creative collaborator of Wu Cheng’en, the Ming dynasty writer who was credited with compiling and writing the first comprehensive edition of Xi You Ji.

Nearly eight decades have passed since Monkey (1943), Arthur Waley’s translation of Journey to the West, was published. At that time, China and the United States were thick allies in the midst of the Pacific War against Japan. Hu Shih, having just finished his term as the Chinese ambassador to the United States, wrote in an introduction with palpable excitement that, thanks to Waley, the story would “now delight thousands upon thousands of children and adults in the English-speaking world for many years to come.” If Dr. Hu might seem overly optimistic by a notch or two, in Julia Lovell’s fluent translation and witty retelling, I see real hope that his prediction will finally come true.

There is something deeply gratifying about a good translation of Xi You Ji that speaks to a global audience. What better tribute can there be to the person who started all this — Xuanzang, the brave traveler-translator who delivered delicate manuscript scrolls across deserts and mountains and helped new ideas transcend linguistic chasms?

¤

LARB Contributor

Minjie Chen works at the Cotsen Children’s Library, a special collection of international children’s literature held at the Princeton University Library. She is the author of The Sino-Japanese War and Youth Literature: Friends and Foes on the Battlefield (2016) and contributes to blog posts about Chinese children's literature at blogs.princeton.edu/cotsen and chinesebooksforyoungreaders.wordpress.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Idiom as Instrument: On Yan Lianke’s “Hard Like Water”

Thomas Chen reviews Yan Lianke’s “Hard Like Water,” translated by Carlos Rojas.

A Search for the Soul of the Mainland

Yunte Huang has compiled a 624-doorstop of an anthology.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!