A Breath of Fresh, Confusing Air in American Crime Fiction

Elena Avanzas Álvarez discusses Megan Miranda’s refreshing take on contemporary crime fiction in “All The Missing Girls.”

By Elena Avanzas ÁlvarezJune 29, 2016

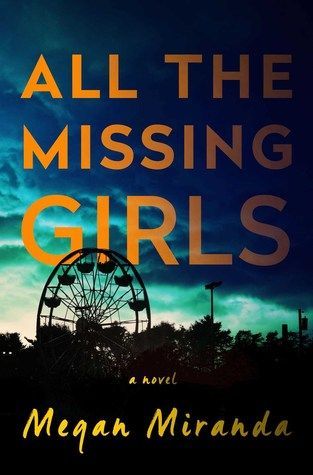

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda. Simon & Schuster. 384 pages.

READING A CRIME NOVEL is a game between the author and the reader in which we never get tired of getting fooled. As readers, the moment we open the book we know that the author has all the clues and the solution to the mystery, but we agree to the process of reading and slowly discovering new information. This pleasure takes a darker turn if we consider that we could solve the mystery by going directly to the last page, but we seldom do — at least I never do. We take pleasure in turning every page, discovering the clues that propel the plot forward. I do not know what Freud would think about this, but I am sure Foucault would remind us of our contentment with the power relationship between the author and the reader and our subjection to narratives. Or he might argue that we accept this subjection because the final restoration of the status quo makes us happy and soothes us into thinking that, eventually, everything will be fine. In any case our situated position as readers turns us into voyeurs to a story that is not ours, but feels like it is. After all, solving a crime depends not only on the detective, but also on the reader who turns the pages and, by reading, makes it possible to restore the status quo.

But this linear power structure has changed dramatically in the last decade, especially in American literature. Most of the crime novels on recent best-selling lists do not follow the classical and conservative restoration of the status quo by a mythical hero, but rather question the whole crime fiction tradition to which they supposedly belong. The most relevant example of the 2010s has to be Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, a novel in which the supposed victim is the criminal, the main character setting a depraved moral tone for the narration. Flynn’s meta-literary crime fiction deconstructs crime fiction from the inside, and she is not alone. Megan Miranda’s novel All the Missing Girls also exults in this new tradition in crime fiction, in which characters subvert power structures and cause mayhem. Both Flynn’s and Miranda’s main characters also reclaim the right of female characters to be more than victim or femme fatale, and thereby disrupt not only the plot, but also the genre itself.

All the Missing Girls, in the American hard-boiled tradition, has a main character and narrator who presents her story in the first person. Nic Farrell left Cooley Ridge 10 years ago and never looked back, expecting to leave her Southern small-town life behind and get a bright new start in Philadelphia. Age 28, she is forced to help her brother sell the family house to pay for their father’s nursing home, now that he suffers from dementia. But the return of the prodigal daughter is never an easy one, and Nic has to face, one more time, the event that changed forever everyone’s lives at Cooley Ridge: the sudden disappearance of her high school best friend, Corinne.

Miranda’s novel plays with crime fiction’s almost fetishist fixation on form and twists it, creating a new reading experience that will surprise many and probably confuse everyone. The narration starts on Day 15, with each chapter going a day back until Day One, when the reader will finally find out what really happened. Although this kind of structure could be tricky, Miranda makes the most of it by relying on her readers’ ability to put all the pieces together with the help of Nic, who is aware of her role as narrator: “I’ve never told it before. This is the only way I know how. I’m getting there.” She justifies her chaotic presentation of events by saying that it is only backward that can she tell her story and unveil the truth. It is important to note that the hide-and-seek game of reading crime is dramatically enhanced by this reversal, yet as in any great mystery, one needs to be fully aware in order to find all the clues and solve the crime. This novel is not easy, light, fluffy crime fiction to be read mindlessly — it requires the reader to work hand in hand with Nic to solve the crimes.

As also usually happens in great crime novels, structure and themes work together. The missing girls of the title refer to the sudden disappearance — in the novel’s present — of a Cooley Ridge girl in circumstances that resemble Corinne’s 10 years ago. A new investigation is set up and the whole town revisits the events and the social patterns of that time, while Nic ponders whether this disappearance is part of a sick game, or a reminder that you cannot leave your past completely behind. Novels by Megan Abbott and others on the female teenage experience have made it clear that girls are rebelling against any stereotype that suggests they are passive and one-dimensional. Miranda goes one step further to think about the ability of female characters to escape their roles as girls. If Amy Dunne was turned into a character by her own parents, Nic has been constructed by her community as Corinne’s best friend, and has been expected to fill that role ever since time froze for Corinne 10 years ago. And when the new girl, also her neighbor, disappears, Nic is forced back into an intelligible category in the police narrative as “the girl,” and wonders whether she still fits into that box or not.

As in the case of Flynn’s Amy Dunne, a new archetype is rising in American fiction and the reading audience loves her. Young, white, beautiful, educated, and with a twisted relationship with her family, this girl is now a prime main character in crime fiction and beyond. She is no detective, and in fact has usually played a morally questionable — by traditional and fixed moral standards — role in the crime narrative that she has decided to share in the first person. As Nic points out: “The facts. The facts were fluid, and changed, depending on the point of view. The facts were easily distorted. The facts were not always right.” This re-presenting of the facts in the first person conveys a sense of confession — creating an intimate and direct relationship with the reader — and constructs the main character’s experience as the legitimate story. Subjectivity is thus a tool of subversion; these girls present the story as they live it, not as the police or some other supposedly objective force wants it constructed. Nic Farrell is aware of the good and the bad in her, and she exposes herself to the reader in all her multiplicity.

The humid, dense, mostly green North Carolina setting is reminiscent of the way David Lynch used nature as a backdrop in Twin Peaks, and Corinne reminded me of cunning Laura (also the name of Nic’s pregnant sister-in-law). The woods and caverns that surround Cooley Ridge’s tight community create a confined and remote space where everyone is lying to protect the town and the town’s golden girls, who are not what they seemed. There are also distant echoes of Fifty Shades of Grey, with Nic’s current fiancé, Everett, a top lawyer from one of Philadelphia’s oldest families. Tall, smart, handsome, and rich, he is portrayed as a mismatch for Southern, working-class Nic. But Miranda lays out the reality behind this Prince Charming, savior of the supposedly inferior damsel in distress in a takedown of all such glamorous retellings of a misogynist story as old as time.

In short, Miranda’s first novel for adults is a breath of fresh air for contemporary American crime fiction. Deeply rooted in the American literary tradition and yet innovative, challenging crime fiction’s fixation on form, All the Missing Girls is set to become one of the best books of 2016.

¤

Elena Avanzas Álvarez is a third-year PhD Candidate at the University of Oviedo, Spain.

LARB Contributor

Elena Avanzas Álvarez is a third-year PhD Candidate at the University of Oviedo, Spain. She has been researching crime fiction with a gender perspective for the last three years and is currently writing her thesis on women’s representation in 21st-century crime fiction. Her research about Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Scandinavian crime fiction, and women’s issues has been published in journals, and her MA thesis about performativity and discourse analysis on the TV show Rizzoli & Isles won the First Gender and Diversity Award in 2014. She is also the founder of Books & Reviews, a blog focused on crime fiction and Women’s Studies. Elena currently lives in Spain with her family and her tenacious Border collie, Sil.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Proper Crime Novel

Katrina Niidas Holm interviews Lisa Lutz about her new novel, "The Passenger".

In Search of the Great Hollywood Novel

Hollywood novels let us see the past, not in long-shot, with the gulf of time separating us from the events they describe, but in brilliant close-up

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!