A Bewildering World: On Max Porter’s “Shy”

Joel Pinckney reviews Max Porter’s “Shy.”

By Joel PinckneyMay 27, 2023

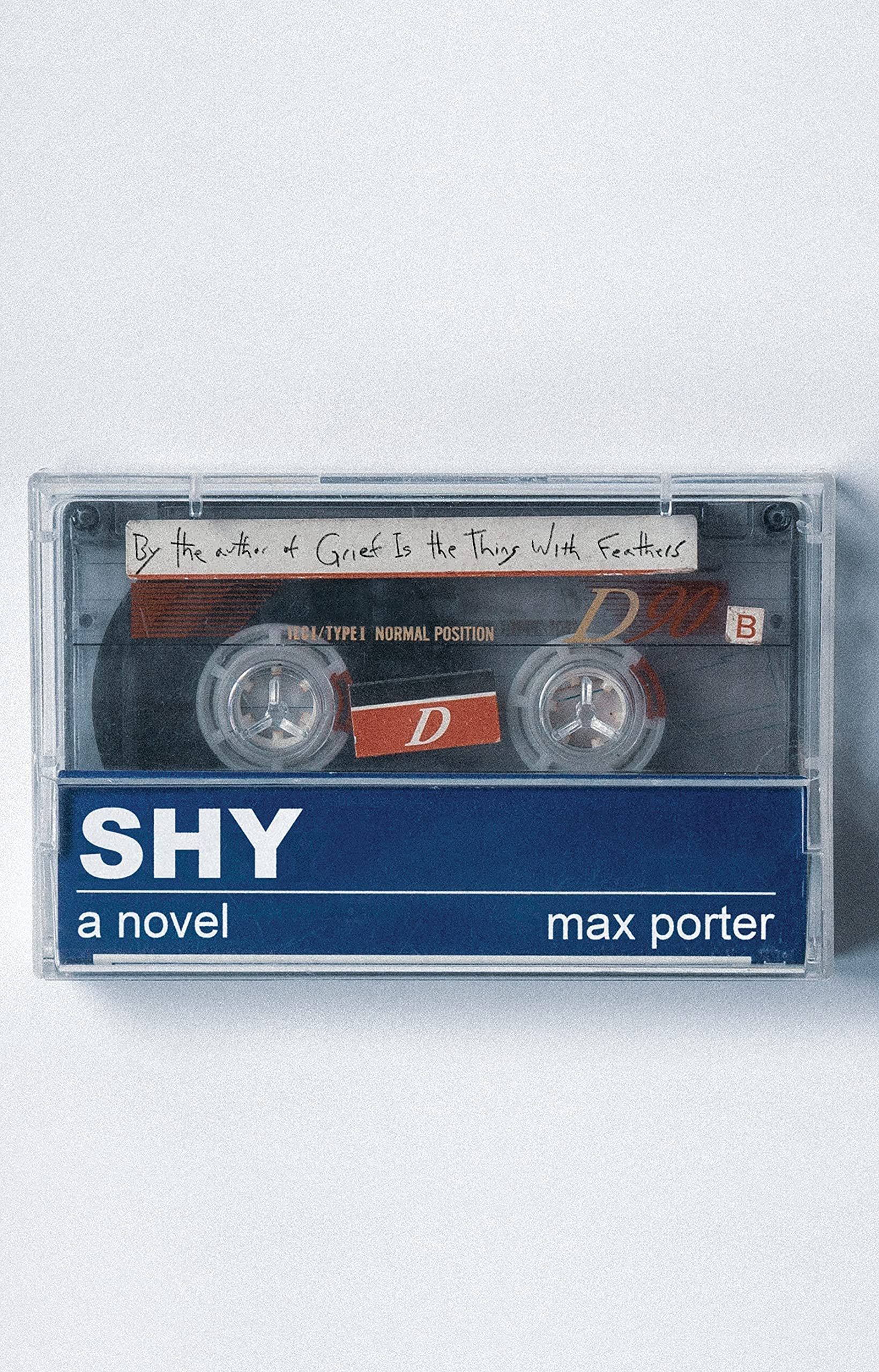

Shy by Max Porter. Graywolf. 136 pages.

IT’S THE MIDDLE of the night, and Shy is sneaking out of Last Chance. His backpack is filled with rocks, and he’s headed for the lake.

There’s a singular compassion at the center of Max Porter’s work. His fourth novel, named after its eponymous subject and published earlier this spring, features the troubled Shy at Last Chance, the rather haunted home in the English countryside whose aim is to rehabilitate young boys like himself. When we meet Shy, though, rehabilitation is far from his mind. Instead, Shy wishes for his last chance to have been taken; he wants it to be over, to be past. Porter doesn’t provide much in the way of context, isolating the reader with Shy in the moment—he is, simply, leaving. Shy briefly removes his backpack at one point on his journey and feels the relief, “[s]omething that was hurting for a long time briefly not hurting.” That’s Shy’s hope on his journey out of Last Chance: to find a relief that’s not so temporary.

As the night progresses and Shy makes his way to the lake, though, it’s not the harm he plans for himself that fills the troubling and troubled pages of Porter’s novel. We don’t witness Shy’s nervousness, his fear that he will not be able to go through with what’s ahead of him. Instead, it’s Shy’s past, and how he feels about that past—his perplexity toward himself and the random and violent things he has done; the boys, and the adults, who have added rocks to his pack, or occasionally lightened his load; his love of music, the music that gets him through.

Porter refuses to conform to conventions of narrative prose—even of the ways text is traditionally arranged on the page—which perfectly suits Shy’s chaotic mind. The book is playful despite the heaviness of its subject matter; from its opening pages, Porter includes variations in type that communicate the ridges and valleys of Shy’s psyche, bouncing between memories, fears, feelings of shame that he just can’t get past. Occasionally, Shy’s mind will catch on an idea or a story, and the text will continue uninterrupted across several pages; in two particularly stark instances recounting words of pleading, words of anger, words of rebuke from his mum and stepdad, the font is nearly doubled in size and the sentences consume the entirety of two pages, not even breaking in the gutter that splits the two sides. The words overwhelm the physical vessel, as Shy’s haunted thoughts and memories overwhelm him.

It is a technique Porter employs throughout his work, a commitment to use all the tools at his disposal to communicate the interiority of his characters. Flip at random through Shy or any other Max Porter novel—in his masterful debut, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers (2015), the text’s movement across the page, the quick transitions between narrators, the cacophonous ramblings of the comforting crow; in his second novel, Lanny (2019), the crawling of words over and upon themselves as Dead Papa Toothwort listens to the sounds of the rural villagers. Porter’s most recent book until now, 2021’s The Death of Francis Bacon, includes passages where spaces and words compress, culminating in some nearly indecipherable pages as Porter seeks to inhabit Bacon in his final dying hours.

Here, other forms add texture: passages pulled from a documentary crew that visited Last Chance to tell the story of the home and the boys who lived there; words of encouragement toward Shy from the staff at Last Chance, recalled by Shy and occasionally breaking through the cacophony of damning memories that haunt him. “It’s a multi-season job, knowing yourself. You’re still in the Spring”—we read this passage as Shy makes his way out of Last Chance, traveling ever closer toward the lake.

It’s not clear, as Shy progresses, whether what we are witnessing are Shy’s final hours. But the reader knows what he intends, and increasingly the reader understands why. Shy has destroyed his life, and he knows it. Shy remembers a fight in which he badly cut a boy’s forehead open with a broken glass bottle—in the memory, he “opens a line straight across the top of the kid’s forehead, unzips the skin and watches a sheet of blood fall down like special effects.” Still, 30 pages later, Shy is thinking about his violent act: “He can’t really hold any thoughts or feelings steady in his head about having done the thing, so he wonders if the lad has any clarity about having had it done to him.” In another incident, friends of Shy’s mum and stepdad had offered Shy a key to their house; he was invited in whenever he liked, invited to use their home as a place where “if things ever got too much he was allowed to sit in their smart kitchen and decompress.” Shy returns their generosity by throwing back their liquors and plundering their home. Everything is too much for Shy, and his self-awareness makes it worse. He is “[c]arrying a heavy bag of sorry,” and he doesn’t know what to do with it or how to stop his cycle of self-defeat.

One of Porter’s generosities as a writer—even as he shares Shy’s story through the winding roads of what is front of Shy’s mind—is that he refuses to diagnose or pathologize his subject. Shy is troubled, Shy needs help, but Porter resists the temptation to provide his readers with a box into which they can place the character. Nor does Porter offer his readers with a story to understand why Shy is the way he is. We are given no insight into a past of neglect or abuse, no look into the life of a child bereft of love—it is clear that his mum and stepdad, along with the caretakers and counselors at Last Chance, flawed as they all are, love and care for him deeply. Shy is, simply, a boy who needs help.

Porter’s refusal to pathologize Shy, to explain him away, lays bare a fundamental question: what is his need, and what can be done to meet that need? It is both a personal and a political question, one that Porter does not express in so many words but which draws its power from being withheld. In a 2019 interview on the podcast Between the Covers, Porter spoke with host David Naimon of the “exactitude that you can achieve with economy,” setting his work against a type of contemporary novel that “tells you absolutely everything, and […] wallops you around with exposition.” Shy, written as the type of novel Porter criticizes, would provide a narrative roadmap to explain why Shy is the way he is, seeking its clarity through A-to-Z. Porter, on the other hand, works in the realm of ambiguity, seeing it as the driver of imaginative possibilities for his reader that create space for understanding, for sympathy, to fill in the gaps. He simply shows Shy’s need, and leaves the reader to imagine what meeting such a need might require.

In a conversation Shy remembers with his mother before coming to Last Chance, she tries to prepare him for the types of boys he’ll encounter, hoping to show him that he is something different—because, of course, to her he is something different. She tells him that at Last Chance there are some “very disturbed young men,” and when Shy insists that he too is a very disturbed young man, she suggests that he is merely lost. Shy responds, “I’m not lost. I’m right where I got myself.” It’s a moment that epitomizes another of Porter’s central approaches to his writing—as he put it in the same interview with Naimon, his “whole philosophy of fiction is that you can quite deftly or quickly, with a turn of phrase or a line, get to the truth of a thing and then leave it there for the reader to become complicit in or to misjudge or even correctly guess at.” This is one of those moments from Porter, imbuing Shy with a level of self-awareness and recognition that has the power to free him from blame, from shame—if he’s lost, perhaps he bears responsibility for becoming lost and can trace what brought him to that point; perhaps he can simply find his way out. But if he’s right where he has always been, the journey becomes something different entirely—a journey not to find his way out but rather to find his way in, to better understand who it is he finds himself to be, and what that leaves him with. It’s a small glimpse of hope for Shy, a suggestion that the self-awareness that so often damns him to himself might also help him on his journey toward healing.

The other glimpse of hope in Shy is the music—the Walkman Shy carries with him on his journey to the lake, “saving the music for later. The thing he always has to look forward to, which will never disappoint him.” The inference is obvious: that others will always disappoint him, that Shy will always disappoint himself. Shy’s reveling in his music provides some of the only levity on offer in this novel, the only genuine joy Shy gets to experience, and it’s a relief to read, as one can imagine it being for Porter to write: “God is a bouncy bastard who wants his people together in the dance. […] Hallefuckinlujah he loves the drums.” The music is a reliable companion to Shy in his confusing and unpredictable world, a constant for a boy whose sense of self is muddled and ever-changing. “That’s why he loves the music so much. It promises, and it delivers.”

But, of course, Shy’s music has not kept him from reaching the place where he finds himself in the tortured hours that make up Porter’s novel. As Shy gets closer to and eventually enters the waters of the lake, other central concerns of Porter’s find their way into the work: an ethic of care for and wonder toward the natural world; a concern for the most sensory of experiences and a desire to sparingly communicate such experience; the connection of humans and animals and efforts to “send a message across a species divide.” All combine to bring a certain level of clarity to Shy’s mind that has heretofore escaped him.

Max Porter’s larger project is sympathy with characters living through a difficult, bewildering world—a father and his sons reckoning with the disorientations of loss in Grief Is the Thing with Feathers; a boy of the earth in Lanny for whom the world offers little welcome; a dying man, confused and bewildered in his passing, in The Death of Francis Bacon. Shy is an emphatic furthering of this project, written out of love for its bewildered subject. It offers a challenge to recognize the complexity of the difficult road faced by boys like Shy, as well as to understand them complexly—to see both their struggle and their joy, to meet them where they find themselves, and to help lighten the load.

¤

LARB Contributor

Joel Pinckney is a writer living in Austin, Texas. His work has appeared at The Millions, Ploughshares, Full Stop, and The Paris Review Daily.

LARB Staff Recommendations

An Image of Itself: On David Grundy’s “Present Continuous”

Tom Allen reviews David Grundy’s “Present Continuous.”

Thinking in Ruins: On the Llano del Rio Experiment

In a preview of LARB Quarterly's upcoming issue, Earth, Laura Nelson explores the Llano del Rio failed commune experiment in the California desert.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!