I wanted to write a memoir but the connective tissue of the memoir didn't interest me. I wanted to render memories that would pop up like mushrooms and quickly vanish. I owe much to where I was raised, in a black neighborhood where people talked to each other and spent time on the porch and on the corner, as did my brothers and their friends as they smoked weed, drank Mickey Big Mouths and Heinekens, and talked all the time about the insanity of Vietnam, nuclear war, and H.P. Lovecraft, and from there they'd segue into the adventures of the many memorable characters in the neighborhood. I tried to do that here. A new installment will appear here every Saturday.

¤

Race depends on where you at in that New Orleans patois. Though I grew up in Los Angeles, nineteen hundred miles away from the Big Easy, I still contended with the New Orleans race subtext. Black people could look white like snow, though I never saw snow except on a screen and I didn’t know white people outside of teachers. But half my family looked like white people you’d see on TV.

It wasn’t really confusing as all that, skin color was as deep or shallow a topic as you needed or wanted it to be. It all depended on where you were at in the head. Your mental health depended on whether you could reconcile how you appeared to others to how you thought of yourself. My parents didn’t look how some people thought colored people should look. They could pass but they didn’t. If you wanted to make that decision to reject everyone in your family who couldn’t pass the brown paper bag test and if you could pass the self-loathing test, you were ready for whiteness.

My family fit into our neighborhood because we belonged there. We weren’t the lightest and neither were we the darkest, though Mama got stopped by the police for driving through a black neighborhood on a regular basis. Police would pull her over and say, “Lady, you shouldn’t be driving through this neighborhood.” She’d thank them, park, and walk to her house.

I could only imagine what the police thought about the pretty white lady living amongst the blacks. And the greatest horror of horrors was that if she was married to a black man and what they thought should be done about it if she were.

That’s how it was. In our neighborhood maybe half of us could pass. Not just half-assed passing but the real deal. They could relocate to whiteboy land and live that lonely life of deliberate ostracization from black folk and the self they were before they made that leap into whiteness, as though they got away with it.

It didn’t help that weird that people would just reappear in the neighborhood and become fixtures like they never left.

Pat was one those people. I think she was the niece of some old lady on Third Avenue, and she looked like a straight beautiful white girl, though I didn’t know any white girls. She was tall and almost skinny but weirdly shapely. Somebody said she modeled. I had no idea of how models looked but she looked like something. I was about twelve and I had a manly crush on her. She was nice and didn’t ignore me when she sat on the porch drinking wine with some of the other young women in the neighborhood. I was pretty much a puppy around her, hoping to get attention. Then she disappeared for a while and Onla said to me that somebody said John Wayne was her daddy.

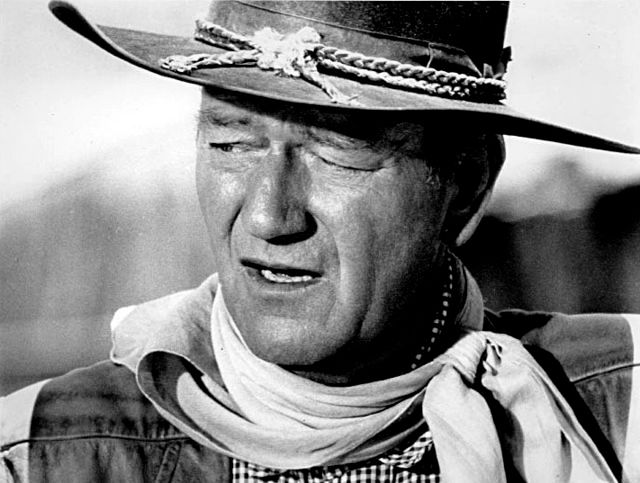

“Shit,” I said. I didn’t like John Wayne even when I was a kid. I knew he was a racist plus he wasn’t cool. Everybody liked Clint Eastwood who was truly cool while John Wayne was ridiculous and creepy.

Pat had a daddy we hated. Then she began looking really white to me, whiter than my brothers Hillary and Jeff. My crush on her was already eroding. How could John Wayne, some racist white man with a weird way of talking, be her daddy? He was just another white man who was a hero for killing Indians in the movies.

Then one afternoon we saw her on the porch of the house on Third Avenue and she had a really big suitcase with her, like she was going to be gone for a long time. We heard from one of the girls she talked to that her dad was coming to pick her up.

John Wayne was coming to our neighborhood.

Googie and I hung out waiting to see if he’d show up and maybe he’d give us something because famous people did that and maybe we’d stop hating him for being a racist. We waited across the street for him to arrive and it took so long that I wanted to go get something to eat at the liquor store. Then finally a big car pulled up and we saw a tall white man behind the wheel. He parked and got out. It was John Wayne. He helped her lug the big-ass suitcase to the car.

“Hi, Mr. Wayne,” Googie and I said in unison, and he stopped and looked at us with surprise.

“I ain’t John Wayne. I’m John Wayne’s stunt double.” And he laughed and handed us some hard candy he had in his pocket, and they drove away.

“He didn’t look all that white.”

“Yeah. He didn’t.”

“They must put a lot of makeup on him,” I said, and we went to the liquor store for tamales.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jervey Tervalon was born in New Orleans and raised in Los Angeles, and got his MFA in Creative Writing from UC Irvine. He is the author of six books including Understanding This, for which he won the Quality Paper Book Club’s New Voices Award. Currently he is the Executive Director of “Literature for Life,” an educational advocacy organization, and Creative Director of The Pasadena LitFest. His latest novel is Monster’s Chef.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!