“This Fairground Farce of Light”: Vladimir Nabokov’s “The Cinema” (1928)

Luke Parker presents his translation of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1928 poem “The Cinema.”

By Luke Parker, Vladimir NabokovDecember 19, 2022

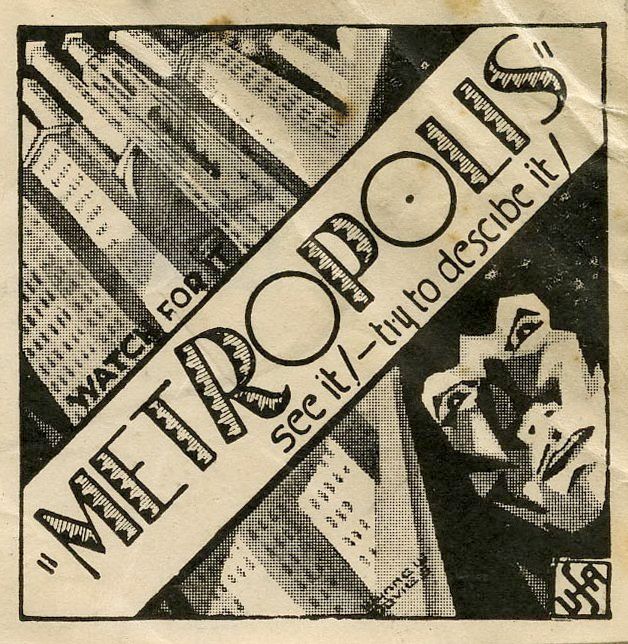

Nabokov loved film, hopelessly. As a young writer in Weimar exile, this Russian aristocrat and Cambridge graduate rented Berlin apartments amidst the city’s countless movie theaters and neon signs, becoming a regular moviegoer. He was less a connoisseur than an avid consumer. Nabokov’s absorption of this mass of films — mostly forgettable, many lost — made him an authority on cinema in the aggregate. It is to these genre films, these sequels and knockoffs, that Nabokov responds in his poem “The Cinema” (“Kinematograf”), and not to the film art and auteur cinema of retrospective accounts. The setting here is not a grandiose premiere in a movie palace. Instead, we are in a corner theater watching a run-of-the-mill American or German release, another product of the Weimar and Hollywood film factories which together accounted for nearly all the films seen by the young émigré in Berlin. Seated among German salesclerks, Nabokov is both charmed and amused. As by all accounts he was in real life: a contemporary recalled the 20-something Nabokov laughing so hard at American slapstick that, choking and shaking with mirth, he had to leave the screening.

“The Cinema,” a piece of light verse which touches upon deeper themes — the relation of inanimate to animate, the place of literature in a media age, the future of Russians among Americanized Europeans — was first published in the Russian Berlin newspaper The Rudder (Rul’) in late 1928. The previous year Nabokov reported writing an essay on the cinema, but if it was ever completed, it does not survive. What we have is this poem: a metropolitan miniature, a confession of love, a gentle parody, and a refusal of snobbery. As a former extra in German cinema, Nabokov recalled the on-set scenes of blaring megaphones and blinding lights imperceptible in the final cut. And as a regular moviegoer he knew firsthand the contrast between auditorium and frigid street, the startling emergence into what he called Berlin’s “alien, electric night.”

But a mocking judgment on the cinema is too easy, the poet seems to say at the end. Yes, film represents only the latest outlet for the eternal “cocksure philistine,” a peddler of what Nabokov later termed poshlust. But third-rate film had the same function as third-rate fiction, according to the hack writer in Nabokov’s 1927 story “The Passenger”: “to prevent servant maids from being bored on Saturday nights.” This surprisingly democratic assessment freed the poet to enjoy the artless yet visceral pleasure of moviegoing. We return, then, to where the poem (and cinema itself, historically) begins: the popular urban entertainment of the fairground, pantomimes now electrified and wrought in light. If the poet has the first word, the salesclerk has the last — and we should note who is the more disdainful.

The Cinema

I love this fairground farce of light

More hopelessly with every scene…

Cunning deceits revealed with ease

By spies concealed across the screen.

There sewing symbolizes good;

A glass of wine must stand for sin.

The keenest eye will find no trace

Of mother’s likeness to her kin.

A rich young man, a tender heart,

Picks homeless girls up off the street

And lays them down in spacious cars,

All tiger fur from head to feet.

Letters are scrawled in dead of night:

Danger, alarm! The pen just flies

Across the page… Yet all the words

Are perfect, flawless shape and size.

We’re shown a boudoir brightly lit,

A shawl abandoned on the floor.

Unseen — the klieg projector’s glare,

Unheard — the wild director’s roar;

But nothing there vibrates with life:

Inquiring guests could scarcely say

What living link ties man to thing,

The imprint of the everyday.

Splendid they are, cascades and chases,

The darkly spinning glass abyss.

But harmony’s delights? Or flights

Of fancy? Muse, you’re dearly missed.

The villain dies, the hero weds:

No matter setting, time or place,

The cocksure philistine will dress

In tritely gorgeous style each space.

The End. In shadow the piano

Dies, after briefly taking flight.

The world returns the cold and noise.

The waking dream dissolves to night.

And out to brave the wind’s damp force

The salesclerk and his girlfriend go:

He cups the burning match, then smirks

And passes judgment on the show.

LARB Contributors

Luke Parker is a visiting assistant professor of Russian at Amherst College and the author of Nabokov Noir: Cinematic Culture and the Art of Exile (Cornell University Press, 2022).

Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) was a Russian-American novelist, short-story writer, poet, and translator. One of the great literary stylists of the 20th-century, in both Russian and English, he is best known for his novels, which include Lolita, Pale Fire, Ada, The Gift, and Pnin.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!