I wanted to write a memoir but the connective tissue of the memoir didn't interest me. I wanted to render memories that would pop up like mushrooms and quickly vanish. I owe much to where I was raised, in a black neighborhood where people talked to each other and spent time on the porch and on the corner, as did my brothers and their friends as they smoked weed, drank Mickey Big Mouths and Heinekens, and talked all the time about the insanity of Vietnam, nuclear war, and H.P. Lovecraft, and from there they'd segue into the adventures of the many memorable characters in the neighborhood. I tried to do that here. A new installment will appear here every Saturday this and next month.

¤

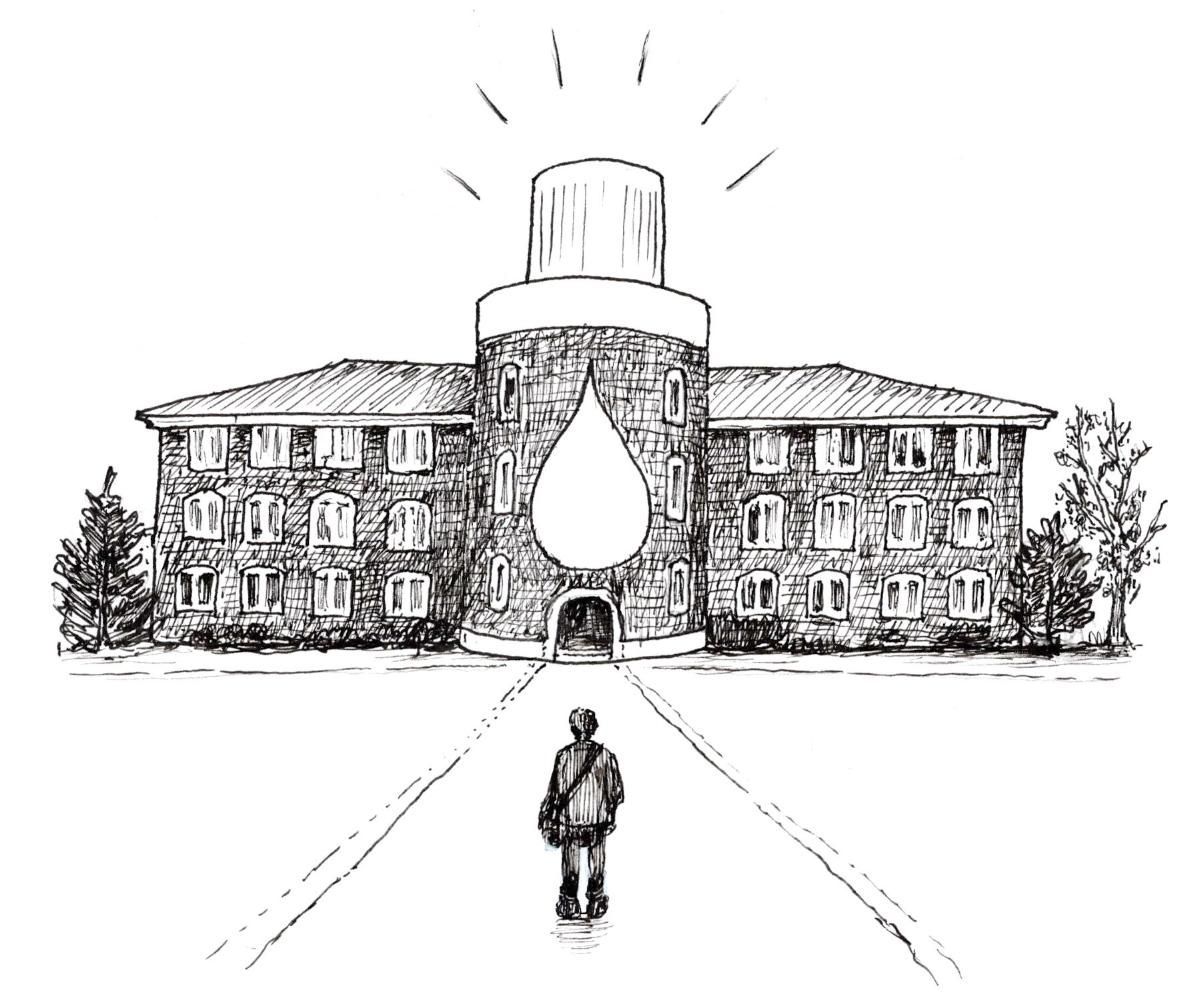

I gave a fellow writer his bachelor party. Friends do that short of thing, but I was surprised that he asked me. We weren’t that close. I mistrusted him on the grounds that his first book was about growing up among black people in Oakland; that alone was enough to make me suspicious of him, but I gave him the benefit of the doubt, probably because I couldn’t bring myself to take him seriously. My ex-wife grew up among whites in rich-ass Montecito and her dad ran for the board of education in Santa Barbara; they had to have a police officer in their backyard because of death threats. She didn’t get a book out of the experience, though. I imagine this guy’s agent saw the monetary value of a good-looking white man writing a Tarzan-in-Oakland page turner. I figured it was all invention, though I came to accept that his experience might have some substance and it’s not all that unusual. I remember a conversation with another white writer who lived amongst blacks complaining about publishing. She said, “You know how they treat us.” Maybe she forgot that she was white, but I hadn’t forgot that I wasn’t. Instead of being on the tenure track path at serious university, I got hired at Saint Mary’s College. I had been published by a major press and had taught as a lecturer at a UC, but what I got for being well-published was a job offer at a half-assed college. I liked Oakland and thought Giselle, our two-year-old, would be comfortable there. I was hopeful when I arrived for my interview on the secluded campus with its Spanish style architecture. I entered the conference room, and it was like most of these interviews, a room full of whites and one person of color. The weird thing was the one person of color looked very much like me but much smaller. I guess I should have found his presence comforting but instead I was surprised and disoriented. Still, he guided me thorough the interview and when it ended he drove me to the dinner they were having for me. I learned that for the first time I had the inside track for a teaching gig.

“Jervey,” he said, “You were too young to remember this, but I lived around the corner from your family in New Orleans. I played with your brothers when we were kids.”

I got the job and I soon discovered just how little they valued me. They offered no housing other than a rental because a professor was overseas for a year. A dean contacted me about when my family would be moving up. It seemed a reasonable question, but given the fact that Gina made four times what I would be earning at Saint Mary’s (I made twice as much teaching high school), and the fact that we had a house in Pasadena (Saint Mary’s was a try out), we hadn’t committed. Gina and baby Giselle came up for the banquet for the new hires and soon after we were seated a black woman came to our table and introduced herself. She was Professor Loving and she was warm to us in a way no one else was, except for Alden. She asked me a few questions and I told her where I had taught before and that I just have a novel Understand This published by William Morrow. She immediately looked alarmed.

“You’ve got a book from a major press! You need to leave now. You don’t belong here.”

I didn’t listen to her but after a few months of flying home on the weekends I wondered if she was right. I did like being in Oakland but the Brothers started coming down on me after my first semester. I received a nebulous evaluation that alluded to students not liking me and my reaction was to think: Fuck those kids. They couldn’t get into a real college, so they had to go to the one with the weird-ass racist priests.

What made the decision to get the hell out of there was when the new hires were compelled to visit the Institute of the Fellow Traveler. It was to be shown the relics of the saints, little bits of bones pasted onto velvet on a tray. I knew I had to quit, and I didn’t like their Christian Brothers wine anyway. The other thing is that, other than Alden’s door with a poster commemorating a gay rights rally, gay students seemed as invisible as black people while all the Brothers seemed angry and aloof.

I quit at the end of the year, but I couldn’t leave Saint Mary’s behind. I got calls from former and current faculty there that were fighting the racism and homophobia. It worked because the media picked up on it and soon the lawsuits bore fruit and settlements abounded. Decades after I quit teaching there, I received a check because of their settlement for systemic racism. Change comes slowly, and soon enough maybe college and universities might have more people of color writing about people of color. Maybe they’ll finally take diversity seriously like USC’s Viet Nguyen, the writer of the award-winning The Sympathizer. When he was running USC’s English Department, he addressed the lack of diversity in the department by taking out an advertisement in the online newsletter of the International Black Writers Association, asking for writers with teaching experience to apply. I applied and he hired me, and I happily taught there to a great group of young writers. One of my students, Jean Guerrero, who couldn’t get into the advanced fiction writing course at USC (not one kid had a Spanish surname), was an amazingly talented writer as an undergraduate who went on to win a major award for her first novel. Then she wrote the book on the loathsome racist Steven Miller and now she’s the first immigration reporter for the L.A. Times.

I no longer teach at USC, though I loved teaching there. When Viet left the English department, the new chair asked me to come to her office and there she told me I was being let go and I would never teach there again. “Do you understand?” she asked as though I was an idiot. I said yeah and left. I found another job and went on to write more books and live the life of a writer. Was that woman a racist? I’m not absolutely sure, but I bet she doesn’t think so.

¤

Artwork by Peter Nye

LARB Contributor

Jervey Tervalon was born in New Orleans and raised in Los Angeles, and got his MFA in Creative Writing from UC Irvine. He is the author of six books including Understanding This, for which he won the Quality Paper Book Club’s New Voices Award. Currently he is the Executive Director of “Literature for Life,” an educational advocacy organization, and Creative Director of The Pasadena LitFest. His latest novel is Monster’s Chef.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!