LARB IS ALWAYS OPEN — open-minded, open access, open for debate, open-ended, open to you.

The Los Angeles Review of Books is a reader-supported nonprofit, providing free coverage of culture, politics, and the arts. Like so many literary and arts organizations, our funding has been upended and we need your support now more than ever. Membership starts at just $5 a month. JOIN TODAY >>

¤

America is wracked with crises: medical, economic, geopolitical, racial, societal. At the heart of all of them is a crisis of relationships: our inability to see one another, to engage other people without the prism of politics or the distortion of ego. Technology, which is now in the middle of our relationships, often seems to be making them worse. Can it help heal us instead?

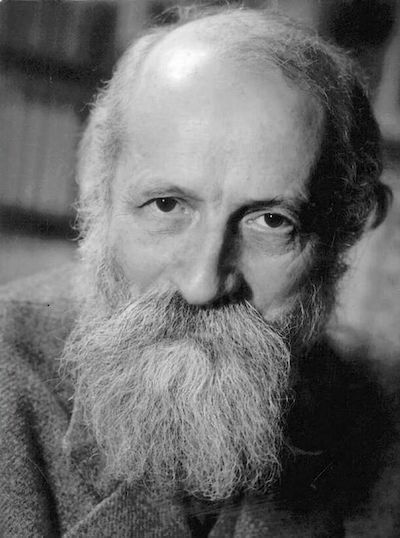

A century ago, the German Jewish philosopher Martin Buber argued that societal dysfunction grows out of an over-reliance on “I-It” relationships, the kind anchored on transactional, utilitarian value. In I-It, we move from experience to experience, asking, “What’s in this for me?” I-It relationships are relationships of use — indispensable but insufficient.

The kind of relationships we need more of, Buber said, were “I-Thou” relationships — full-hearted, reciprocal encounters from which we seek not to wring value, but to attain shared awareness and appreciation. Such moments lead to mutual fulfillment, meaning, and joy. For Buber this was a theological statement — every deep human encounter pointed to the Divine. But even without the religious dimension, his words awaken us to more significant interactions: in Buber’s words, “All real living is meeting.”

As America reels, who is looking out for such living and meeting? Who in our society is accountable for human connection?

Increasingly, it is the tech companies. COVID-19 has accelerated what was becoming true already: technology is central to almost every human relationship. For months now, the only way most of us have been able to work, study, party or pray is on Zoom or Teams.

Tech is not just virtualizing human relationships; it is also shaping them.

Which means that if we want more I-Thou, tech companies have to help. We know they can do connectivity — can they do connection?

It’s easy to be skeptical. Facebook and Twitter’s engagement-hungry algorithms exploit our appetite for negativity and divisiveness. Instagram’s original “like” feature was linked to increased teen anxiety. Even Zoom and Teams can be said to tug us toward I-It: every day now we show up to one another as audiovisual squares, who with the click of a mouse can be hidden, muted, and minimized. As human beings, we are increasingly app-like ourselves, easy to summon and easy to close.

But tech is also capable of ennobling us, of raising human consciousness in a lasting way. As photographer Dorothea Lange observed, “The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” PowerPoint trained a whole generation of information workers not just to put information on slides, but to be more persuasive (narrative assertions on top, supporting proof points below). YouTube taught people not just to upload their social lives, but to reimagine their skills as shareable, valuable content.

If tech companies were to put relationships, instead of individual users, in the center, things would look different.

Product design, instead of aiming to maximize attention and clicks, would prioritize non-verbal interpersonal communication. It would favor features that embrace the totality of a person: eye-contact, body language, and a capacity to “read the room.” It would not feel complete until the possibilities for individual interaction in a group setting, those moments when understanding passes silently between people, were as real online as off.

We’ve seen early glimmers. Everyone was surprised when WhatsApp and Slack challenged the eminence grise of email, but it turns out that those three winking dots in chat, which tell you the other person is working on their response before you get it, touched a deep need — even at work. As Buber taught, we need not only to see each other, but to see ourselves being seen.

Indeed, we need genuine reciprocity even in the most transactional of settings: the work meeting. We need it not just because everything these days, from a chemistry class to a cocktail gathering, feels like a work meeting. And not just because our work days have gotten longer, not shorter, with COVID. We need it because, as Buber said, authentic encounters with other people elevate our very “living” — the awareness, curiosity and imagination that separate us from machines in the first place.

The old tech companies understood this, at least metaphorically. “Ma” Bell wasn’t maternal for nothing. Later reincarnated as AT&T, she urged us to “reach out and touch someone” — not just trade information with them. Today, if tech companies put relationships in the center, they might ask at the end of a virtual meeting not “How was the call quality?” but “Did you and the other participants come to a common understanding?”

Too much online interaction today is performative, encouraging us to put forward versions of ourselves that aren’t real. And while there is no algorithm for authenticity (yet), an I-Thou orientation at tech companies would push them to reward reflectiveness over instantaneousness, permit silence without awkwardness, and create the sense of genuine presence.

The tech companies may say, at first, that relationships don’t spend money, people do. They may say that by helping us all shop, work, and learn more efficiently, they are giving us back time for whatever’s important to us, like relationships. But if what’s important to us, and to the health of society, is greater authenticity and empathy — the expression of which they now mediate — then they need to help with the outcome, not just the potential. They have the brainpower and resources to do it. And with societal frustration against them rising, this may be just the kind of positive vision they can use.

As a nation, we need relationship help. If not the companies connecting us, who?

And for God’s sake, if not now, when?

¤

David Wolpe is the Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles.

Kinney Zalesne is a General Manager of Corporate Strategy at Microsoft.

LARB Contributors

Rabbi David Wolpe is a visiting scholar at Harvard Divinity School and Max Webb Emeritus Rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles.

Kinney Zalesne is a General Manager of Corporate Strategy at Microsoft. She formerly served as Executive Vice President for the United States at Hillel International, and was the collaborator on the bestselling book and Wall Street Journal column Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow's Big Changes.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!