A word broke in two the other day, right in front of my eyes.

A familiar word: automotive

becoming

auto

motive,

breaking into unfamiliar meanings: auto (self); motive (reason for acting).

I had been thinking about a film I adored but didn’t quite understand.

Auto motive: a key?

The self is the reason, the motor for acting

Acting?

In the film Holy Motor, a man has a reason for acting, a motive, a motor.

He is performing himself.

A film in which a man is running, in black and white, first one way, then running back. He is a silent movie. A man who is only automotive. A man as made by Jules Marey, the man who “began” cinema, who began the phases of movement of the moon of cinematography, a man who captured motion as later in the film the man who is the performer will perform a dance of motion capture.

Quick — freeze one frame of interpretation — the cinema is a motor and it is holy.

A man is running in the past; then what are those horns braying behind his automotive stylized past?

They are the horns of traffic, of cars, of the present.

What makes the Carax film so free — “liberated” is perhaps a better word — is that the man seems to operate without a past; time plays no role, nor does its playmate, memory. The only past he has is the fun-house of endless reflection, so that the person may or may not be the person, a past may seem to be the past but then is revealed as only a scene — and a scene is different from a past, isn’t it? Different from a memory? A scene can play tricks.

Well, doesn’t memory plays tricks? A memory may seem solid, but here it is a wall through which we walk along with the hero, the incomparable Denis Lavant whose capacity for transformation astonishes.

A man in bed in the middle of nowhere; the bed beside his empty; he is alone.

In fact, he is almost humorously (at least to me) existentially alone. He wanders, a somnabulist, groping in dark glasses through a room, a television set on, beside a window, a city outside, a plane is landing.

His wall is a mural. His hands search birches, like a blind man. He is feeling his way.

His finger finds the lock

He turns it

He pushes and pushes

He crashes through and walks upstairs into a projector’s beam,

into a cinema among static spectators, a still,

where he is the only man moving. Where he is the automotive.

Where a mastiff prowls the aisle, the endangered aisle of cinema. What rough beast slouches?

He feels his way.

A child in a round mirror, trees behind her, her hand splayed out on a window; a phantom in the iconic pose of Meshes of the Afternoon: she annunciates this film, yes, a film of references, to a purpose which is first (but only first) cinema. Edith Scob portrays his chauffeur named Celine ( a goddess’s name, a French woman’s first name, a brand, a French author called “an absolute bastard”), Scob referencing the character she played years ago in Eyes Without a Face, Georges Franju’s horror film, about the process of “heterografting – the transplantation of living tissue from one biologically compatible organism to another … as a means of preserving and re-capturing youth.”

Eyes Without a Face, dir. Georges Franju (1960)

The mask, always the mask, which is also the mask of Phantom of the Opera, of a gargoyle in Notre Dame, of Victor Hugo’s Hunchback therein, of a French sewer, all of these tropes that casually whisk by in Leos Carax’s Holy Motors, a film of such brilliance that to watch it is to blink one’s eyes in holy amazement. I say holy; yes.

Auto motive — Cinema is self, the maker. Cinema is motor, the actor. Cinema is holy.

and then

the “action”

begins

a Corbu-like white house; children are bouncing a ball on a balcony; “dad” leaves the house in an executive’s suit, carrying a briefcase

“see you tonight dad”

as he walks toward a black car that we expect he will get into but no, this car follows him past a guardhouse with men and machine guns on roof; reality is collaborating with the role he is about to play.

“Bonjour, Celine,” to the waiting woman.

and there it is the white stretch limousine.

“How many appointments today?”

“Nine.”

The executive opens a file

quotes figures, financials, puts on headphones;

talks:

“We’ve got to get guns”

he is talking danger,

takes off headphones; we are in Paris; we are in plot.

takes off his jacket, puts it on hanger, flips on the lights surrounding a make-up mirror, takes out a wig, long hair, “female,” brushes it; we are in a world amiss.

Plot has gone off the rails.

Bonjour, Oscar

another man is in the car

criticizing the performance

Oscar says, “I miss the cameras — now they are smaller than my head.”

The other man says, “Don’t be nostalgic, sentimental, thugs don’t need to see.”

He is … he is … well, he is the executive producer, the car a heartless studio,

the actor its heart.

The man is scarred, bloody

What makes you carry on Oscar?

His answer: the beauty of the act

What is beauty, M. Oscar?

In the eye of the beholder

And if there’s no more beholder?

His job threatened

Cinema threatened

The next appointment

The next and next and next …

The man is voracious; he is alice in wonderland driving through the looking glass, chomping on flowers, on leaves, on a woman’s hand, he is Goya’s giant made small but still thrusting children in his mouth, he is an avatar, an acrobat, arrayed in signals of motion capture, dancing a duet of animal passion, of death by snake, a single man on a treadmill, a man in a luxe hotel on his deathbed caressing the hand of his dear niece, he dies, he is resurrected, goodbye, see you again? a professional to another, rising up to become a professional assassin, to kill his brother who is the twin of himself, also shot dead, lying on the self-same ground

And the next and the next …

A car going up the Champs Elysee

suddenly he (seems to) break from the routine

“Stop the car!”

Gun in hand he runs across the street

shirtless in a feral red hood

A cafe where the banker sits; he shoots the character he was in the beginning

The portfolio again

last appointment?

yes.

you’re ill

I think I caught a cold killing the banker.

Scob lights a fire — there is a grate in the car — he unpeels his wrinkled face

goes through a gorgeous hall of dissolving mirrors

he is The Lady from Shanghai, the dissolving mirrors of self

in front of La Samaritaine department store

he “runs into” Kylie Minogue in another car —

seeming like an accidental meeting between appointments.

She has a Hitchcock face (the alluring passivity of Kim Novak)

hair in french twist.

She is called Jean (Seberg), in a trench coat, from another film,

it is noir, it is night.

Is that your hair?

they made me older.

Are they your eyes?

No they’ve made me Eva Grace, an airline stewardess

living the last year of her life.

A grating; they bend down and under it, come out

into a gutted store

La Samaritaine

They’re turning it into a luxury hotel.

Another thing no longer adequate; no longer wanted.

Like cinema.

They walk on plastic tarps.

We have 20 minutes to catch up on 20 years

She sings, Jacques Demy,

walking away from him,

who were we? when we were who we were ? back then?

runs toward him; violins, Deborah Kerr,

there was a child

The strings swell

we once had a child

I’m sorry.

Lovers turn to monsters and yearn to be far apart

They climb up the stairs, do they have Vertigo?

They are on the roof; the huge letters of a sign,

backward (of course): LA SAMARITAINE

there’s something you don’t know

— about you?

— about us.

time is against us.

I’ll be going.

he’ll be here any minute

it’s better that he and I don’t meet …

he walks away turns waves she waves and …

takes off her coat; She is in her stewardess uniform. Takes off her wig; shakes her brown hair. She has become another person.

Another person?

Takes off her shoes, climbs over the roof railing and inches along the letters of the sign, and … and … turns around: stands at the ledge, the street way down below …

Cut.

He is walking down the stairs, sees the man, the other man, who is going to meet her —

he hides

the other walks up the stairs: Jean is that you? Jean Jean?

The white limo is there, as always waiting for him

but in front of it is a body. Her body.

he caws, a crow, a bird, the Bird(s) —

runs

jumps into the limo

Monsieur Oscar: “we are obsolete Celine”

The film is a threnody to the cinema that Carax loves and sees in its death throes

But cinema too has a purpose here beyond itself, it too is a refraction. The references are not only a game of Can You Find the Reference? but to the illusion that is us, believing that we are auto-motive but perhaps propelled, believing that we are acting our lives when we may be only acting scenes under someone else’s direction, believing we are meeting the memories of a loved past on the roof of a building when we may only be meeting a memory of a Hitchcock film which itself is a memory of the illusory other, the woman who eludes, escapes, climbs, ultimately on a sign — the Hollywood sign, the face of Mount Rushmore, the window through which James Stewart peers into the lives of others, the sign that is a sign of La Samaritaine, the alphabet of letters from which we, along with the “character” throw ourselves off. Among other things, Holy Motors is French philosophy.

A man is performing himself.

La Samaritane?

The Parisian temple of consumer goods, now gutted, and also the Samaritan of parable, of which Wikipedia tells us that “a traveller … is beaten, robbed, and left half dead along the road. First a priest and then a Levite come by, but both avoid the man. Finally, a Samaritan comes by. Samaritans and Jews generally despised each other, but the Samaritan helps the injured man … Tell us that portraying a Samaritan in positive light would have come as a shock to Jesus’ audience. It is typical of his provocative speech in which conventional expectations are inverted.”

Unwittingly Wikipedia is telling one of the many refractions of Holy Motors, a film so deceptive that we think we are interpreting it as the a story of an actor, of identity assuming many roles and thus being plastic, of an actor in a cinema, of this actor as a parable for us as actors. No. We go deeper and deeper; we climb over the sign LA SAMARITANE with some of its letters burnt out, we throw ourselves off, we look down at the body, we go on to the next episode.

you really must eat

he is in a dressing gowon

looks like an odalisque

we must laugh before midnight

before the chimes?

who knows how long

a long day, she says

we’re all drunk

we’re all drunk and dead

Oscar it’s getting late

Celine parks the limo.

He turns out lights in make up mirror covers the mirror with black cloth

she gives him the money for tonight

see you tomorrow

Standing next to her, he is tiny

he thanks her

Celine gets back into car

we hear

a song

we would like to live again

but that means we’d like to relive the same thing (piano)

make the long journey once more

touch the point of noreturn

and feel so far away from our childhood days

and when we’re cold we think

we’d like to live again.

that means we’d like to live the same things afresh

our time has not yet come to rest

we have to do what we love again

dive once more

into the cold liquid days

He is “home,” enters a suburban petit bourgeois house

It’s me, he calls out.

It’s me?!

It’s me?

The fundamental sentence of identity?

Darling!

An ape enters.

How is our baby Luce?

How is our baby, light?

He and the ape hand in hand

at a cerise window

looking out

my dears

i’ve got some news to share

The song

our life is about to change

we see ourselves start again, feel

the sap rises inside us

but it cannot be

no it cannot be

no it cannot

A film without mechanics — narrative or otherwise — an episodic form through which we advance, without explanation, each episode promising narrative but never giving us the end until the end.

Is this not cinema? Is this not life? Is this not THE END?

No. Now we are with Celine driving at night in the car

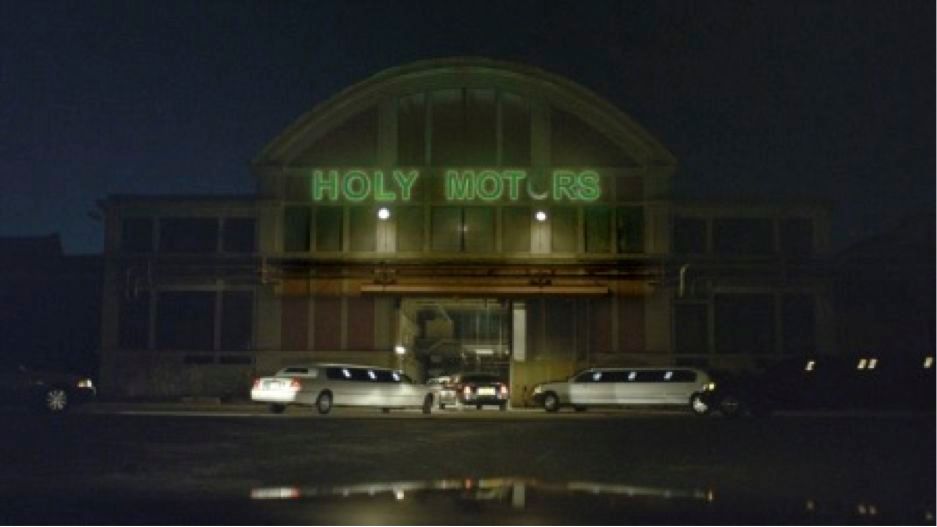

into a garage called HOLY MOTORS, the light on the O almost burned out

Celine releases her tight French twist into a spray of blonde, taking years off the Scob of the 1960 Franju film, becoming young again, as the song of Holy Motors says it cannot be — but it can be, in cinema.

She puts on a mask, a phantom of the opera mask, a Franju mask.

She makes a call

I’m coming home

she walks down an aisle, a bride,

beside her are all the white limousines, parked at a slant,

her bridesmaids.

She turns off the lights.

The white stretch limousines left alone in their stalled spaces speak: we hear their murmured voices conversing.

A yawn.

“My client spent the whole day crisscrossing the city

I’m dead.”

Red backlights blink on and off as different cars talk in different voices

I’m trying to get some sleep

It won’t be long before you sleep

before the junkyard

we’re becoming inadequate

silence

an old man’s voice

men don’t want visible machines any more

we don’t want no more engines

no more action

muttering, all of them,

amen

amen

It is a congregation, a meeting, even a conclave. At the end, on the word they all atone, one almost expects smoke to be sent up, annunciatory of a new election, a passage into grace.

The man who has performed in a white stretch limousine, who has peered into a bulb-arrayed looking glass, making himself up, must exit.

A boy in an silent film throws a stone.

The End (?)

An automotive/ autobiographical note:

I have always loved cars, I especially love the wrecked, dented, wounded, weary ones, especially when they are reclaimed by light and transfigured into photographic splendor. Where did this come from? My father, a cabdriver; seeing him as more than a wreck, more than wounded and weary, becoming my photographs.

Splendor, Janet Sternburg, 2001

Fracture, Janet Sternburg, 2009

Holy Rust, Janet Sternburg, 2009

LARB Contributor

Janet Sternburg is the author of White Matter: A Memoir of Family and Medicine(Hawthorne Books, reviewed in LARB here). Her previous memoir, Phantom Limb (American Lives, University of Nebraska) is also at the intersection of personal life and neuroscience. Other books include Optic Nerve: Photopoems (Red Hen Press) and the two volumes of The Writer on Her Work (W.W. Norton). A fine art photographer. Sternburg has exhibited her work in solo shows in Berlin, Korea, New York, Mexico, Los Angeles, and Milan. Her photography publications include Aperture and two monographs, both published by Distanz Verlag (Berlin): Overspilling World: The Photographs of Janet Sternburg (2016), and this month, I've Been Walking: Janet Sternburg Los Angeles Photographs (September, 2021).

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!