Another Look at India’s Books: Sarabjeet Garcha’s “Lullaby of the Ever-Returning”

In this column, Saikat Majumdar discusses books from India that haven’t received due attention.

By Saikat MajumdarSeptember 14, 2021

In this column, Saikat Majumdar discusses books from India that haven’t received due attention.

¤

Without the concrete there is no experience, and without the abstract there is no understanding. Frequently conceived as two poles in the creative employment of language, the concrete and the abstract enact a ceaseless tension that is the very soul of the reading experience. It is true of all literary forms – in fiction, sometimes it plays out in the relation between the use of the telescopic and the microscopic lenses. But a compassionate and sensible relation between the concrete and the abstract is the very throbbing heart of certain kinds of verse.

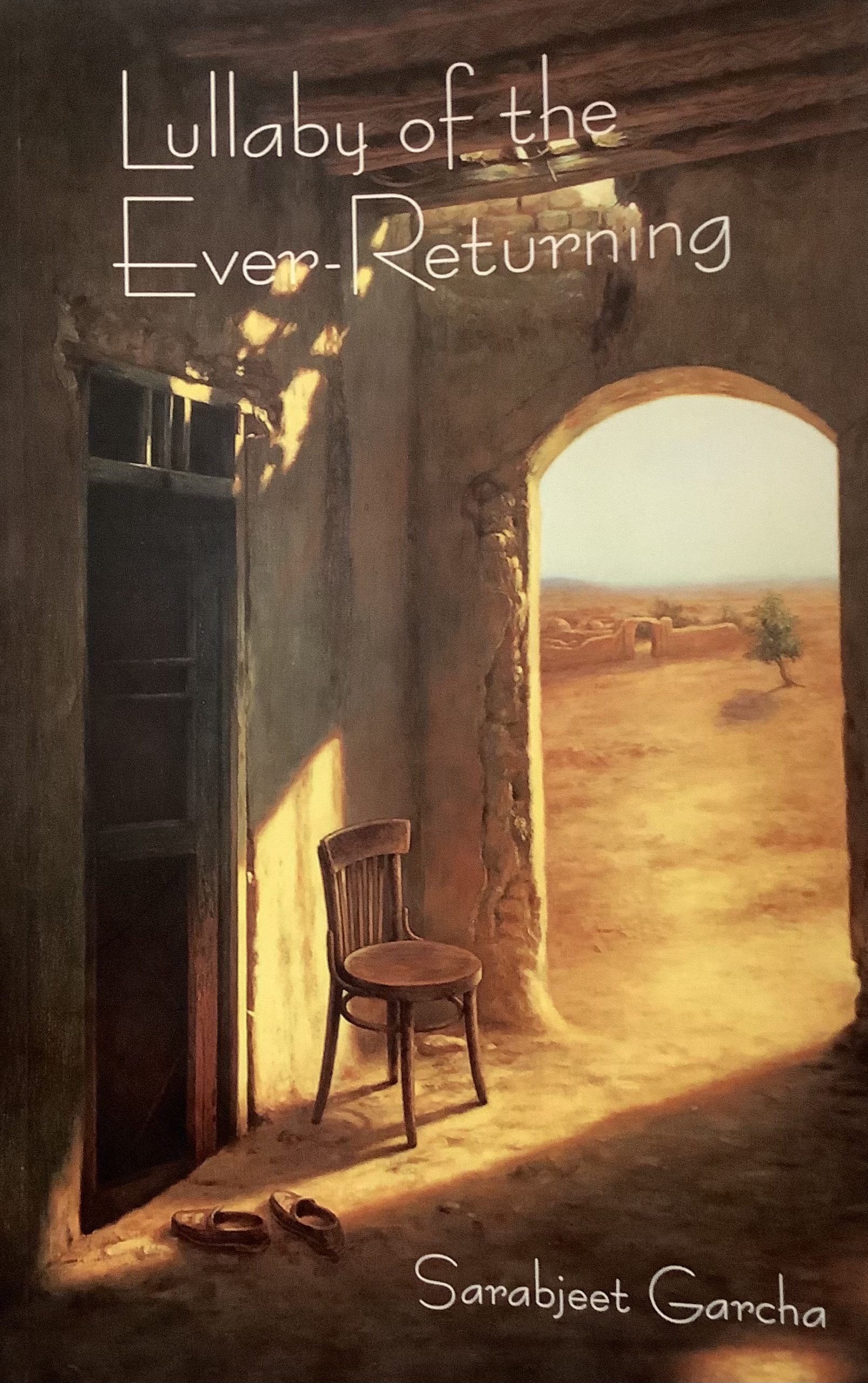

Sarabjeet Garcha’s slim collection, from one of India’s most interesting and wide-ranging poetry publishers, Poetrywala, is a deeply memorable instance of such verse. Lullaby of the Ever Returning is beautifully crafted without the prickly arrogance of craft, vulnerable in its humanity, at once ancient and childlike in its invocation of private and communal memory. It is this voice that, for instance, in the poem “Generosity”, enables the paradox of generosity to shape the energy of enmity:

I could forgive

my enemies

but that

would mean

such a waste

of all those

long years

I took to

accumulate them

Garcha has a poet’s mythical sense of time, even when he is taking a close look at immediate reality. He knows well what it means to feel eternity in an hour; but he also knows the reverse, to see a grain of sand in the whole wide world. Such a mythical, endless sense of time is striking in a poet whose love for sensory experience brings together bread and book:

Elsewhere, hunger shrieks a hallelujah

in ears deafened by slogans

and fingers crave the feel

of unleavened bread

as a bibliophile lusts for the

leaves of an out-of-print book

He is also a very physical poet in another sense: in being deeply, almost subliminally rhythmic, in the sense of possessing a delicious music that you feel, not at the tip of your tongue, but inside it, a live, purring animal trapped within your flesh. Such is the circle of music within which he captures the meaning of Sikhness, the very meaning of family:

One day on the Ahilyabai Holkar Bridge

my brother smashed a mugger’s teeth

with his ridged iron bangle,

one of the solid Ks that encases

a Sikh’s wrist

as if in a guru’s

thumb-and-finger manacle

or reassurance

I would use mine to plant

noon-kindled glares into

my classmates’ bored eyes

Sensory appeal, in the poem, draws its shine from the bloodied richness of history:

was as if the

glint from Guru Gobind’s jewelled

sword had doused Grandad’s backcombed silky hair

Embodying Garcha’s preoccupation with the material and the tactile, the earth is a primal repository of memories. Falling down, in “The Drunkard’s Rituals”, becomes a magical way of dreaming up multiple past lives:

On falling down

he would kiss loose dirt,

taste its texture,

gulp its grammar so that,

by the time his legs could

give him back his dignity,

he would have hush-hush

chronicles of lost civilisations

swirl in the solitude

of his mouth.

The haunting epigraph to the collection, the lines by Alicia Ostriker, have a strange relevance to India today: “Some claim the origin of song was a war cry/some say it was a rhyme/telling the farmers when to plant and reap/don’t they know the first song was a lullaby/pulled from a mother’s sleep”. These words, unleashing Garcha’s sensory rendering of historical memory, resonate with the war cry the Indian farmers, many of them Sikh, have raised against the escalating neoliberal machinations of a vindictive and intolerant national government. Garcha’s English poetry is indigenous in multiple senses of the term, the way it touches soil, bread, and memory. Such poetry, while easily lost in the noisy bustle of mainstream English-language publishing in India, nevertheless draws attention to the vital work done by Hemant and Smruti Divate’s bold and experimental small press, Paperwall, and its poetry imprint, Poetrywala in leavening the landscape of Indian poetry since 2003.

¤

LARB Contributor

Saikat Majumdar’s most recent books are The Amateur (2024) and a novel, The Remains of the Body (2024). He wrote the LARB column Another Look at India’s Books from 2020 to 2022. He is the author of four previous novels, including The Firebird/Play House (2015/2017) and The Scent of God (2019); a book of criticism, Prose of the World: Modernism and the Banality of Empire (2013); a book on liberal education in India, College: Pathways of Possibility (2018); and a co-edited collection of essays, The Critic as Amateur (2019).

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!