In this column, Saikat Majumdar discusses books from India that haven’t received due attention.

¤

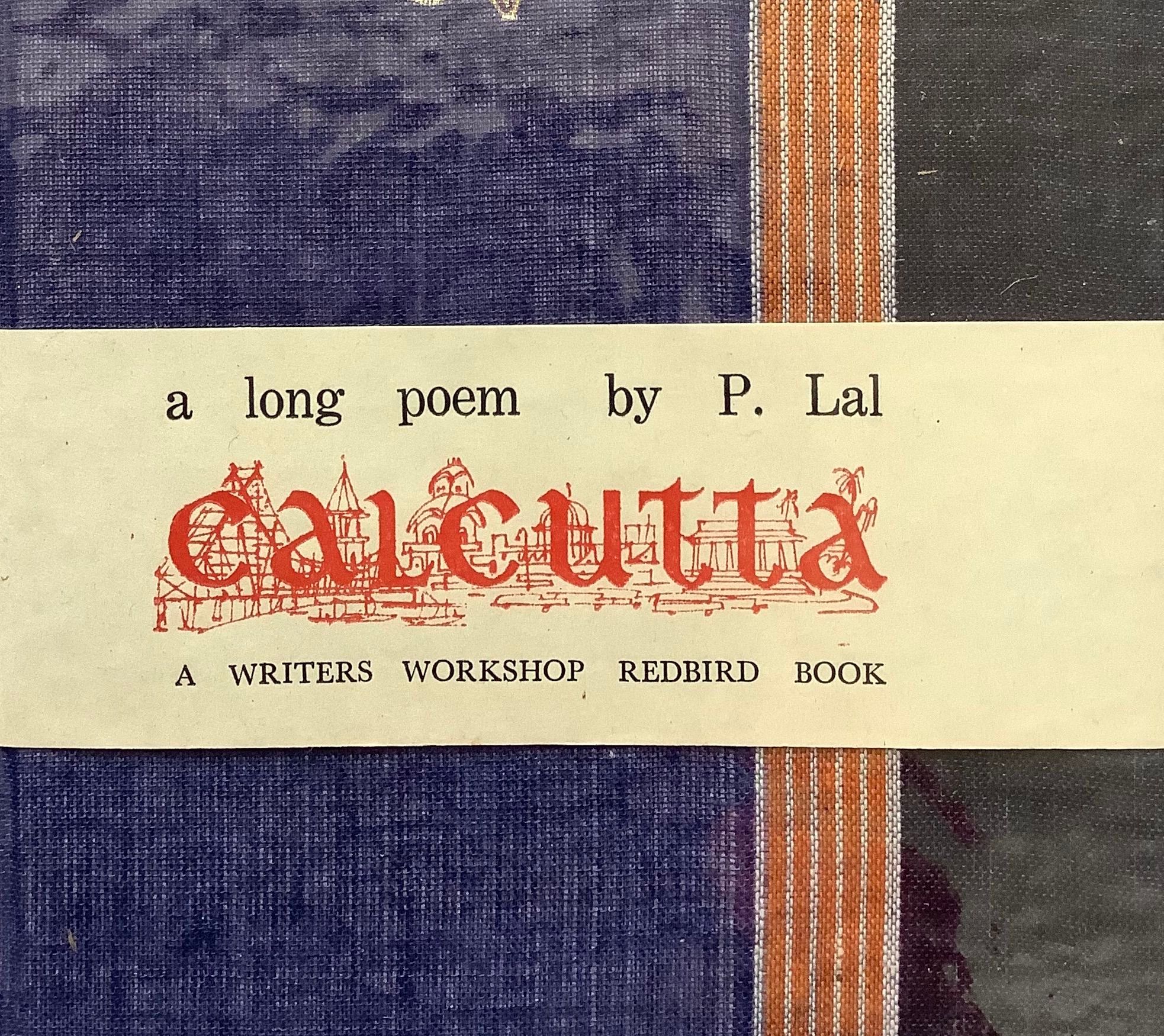

Purushottam Das Lal’s Calcutta: A Long Poem was first published in 1977 and reprinted in 1996. I have the younger edition with me. It has a unique smell, one that belongs to old books of a particular generation — a sweetly acrid, wooden melancholy, redolent of a room overcrowded with volumes that hasn’t had a window opened in years. In many ways, the smell defines Calcutta.

It is the most important work of original poetry by a defining member of a generation of poets who helped English-language verse become a meaningful form of expression in post-independence India. Along with Dom Moraes, Nissim Ezekiel, Jayanta Mahapatra, and others, P. Lal (1929-2010) staked the ground for Indian-English poetry when English still carried the political and aesthetic stigma of colonialism. Professor Lal — as he continues to be remembered — preached powerfully through his own practice. He founded Writers Workshop, the Calcutta-based publisher that released works by some of the most influential writers of the era, all the while creating a corpus of poetry and essays that celebrated the vernacular energy of English in the decolonized nation.

Ancestrally from Kapurthala, Punjab, Lal evokes a time when the great colonial city of Calcutta drew migrants from all over the the country, who came looking for art, politics, and commerce — an unlikely scenario for the city of today. The simmering mélange of tones that sounded throughout the mid-century cauldron of the city feels perfectly suited to Lal’s poetic idiom, which combines romantic effusiveness with classical restraint, the sharpness of Aristophanic satire with the mellowness of Shakespearean comedy. In many ways, Lal is like an Augustan poet — a figure like Pope or Dryden, who watches, admires, and disdains the human comedy of modern urban civilization. But the pall of T.S. Eliot also hangs over his verse, as he sings of a city of corpses and gutters. He’s the melancholic modernist who drums in heroic couplets and paints the plight of Mr. Mervyn D’Mellow:

Nowhere to go, the trams repeat,

Nowhere to go on calloused feet

Beggarboys come runnin’, cryin’ “Sa’b, Sa’b,”

Oh bugger off, I lost my job.

His portrait of Mother Teresa, a figure central to the poem, is both ethereal and irreverential:

Mother, with the pollen of the sunflower of your love

place a golden tilak

on the foreheads of the following

itemised for your convenience

1: The lady in the see-through voile

She sails in a sea of brunches and elevenses

Sliding into port for snacks and triscuits.

Her eyes are bright and dainty

Parlé biscuits circled with mayonnaise.

She crunches at carrots with vegetarian valour.

She floats in a flurry of light blue,

Her favourite colour, such a soothing colour for nerves,

Such azure fragrance,

Such an overpowering presence of empyrean supremacy.

From her milkwhite satin petticoat

Silk-embroidered stars

shiver and fall

wherever she goes. Such music!

Calcutta is a remarkable formal experiment by a poet who is steeped in classical Sanskrit poetry while also carrying on a rich personal relationship with various traditions of Anglo-American poetry. Many of the verses cluster around individuals from different cultures, idiosyncratic denizens of the megapolis. Some figures and rituals stand out, as etched in the charming essayistic interlude adorned with evocative pencil sketches: Bengali women, Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali wedding feast, and the adda (“translated limply as free-for-all discussion”), culminating in the great Hindu carnival, the worship of the ten-armed, demon-slaying goddess Durga.

The poem pioneers a drunken ethnography all its own. Images of people and places are cartoonized with intense lyricism. Together, they become a throbbing document of post-independence exuberance crafted by a key figure of Indian-English poetry, whose name has been woefully out of circulation since his death in 2010. Lal’s image has faded outside poetic and academic circles in Calcutta, but even there, his dense, evocative, tragicomic poetry is often eclipsed by the historical importance of Writers Workshop, the small press that carries on the mission of publishing bold, experimental literature under the tutelage of his son Ananda and granddaughter Shuktara Lal. It is long past time that we bring Lal’s verse out of the shadow of neglect.

¤

LARB Contributor

Saikat Majumdar’s most recent books are The Amateur (2024) and a novel, The Remains of the Body (2024). He wrote the LARB column Another Look at India’s Books from 2020 to 2022. He is the author of four previous novels, including The Firebird/Play House (2015/2017) and The Scent of God (2019); a book of criticism, Prose of the World: Modernism and the Banality of Empire (2013); a book on liberal education in India, College: Pathways of Possibility (2018); and a co-edited collection of essays, The Critic as Amateur (2019).

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!