Writing a book is luxurious. It is the luxury of Virginia Woolf taking 146 pages to accompany Mrs. Dalloway as she prepares for and hosts a party, of Jane Austen spending 276 pages strumming our nervous systems as she slooowly brings Elizabeth and Darcy together, of Jim Bouton taking 400 pages to show all of American life through the diary he kept while a member of the 1969 Seattle Pilots baseball team, and of Stephen Ambrose spending 2497 pages in three volumes to describe what in the hell got into Richard Nixon anyway.

The inherent luxury of writing a book, of applying riches of time, intellect, emotion, and craft to a single subject, breaking it open and exploring its chambers as one eats a pomegranate, begs an important aesthetic and perhaps even moral question: How do we use a form that is the function of luxury to depict its violent opposite — poverty?

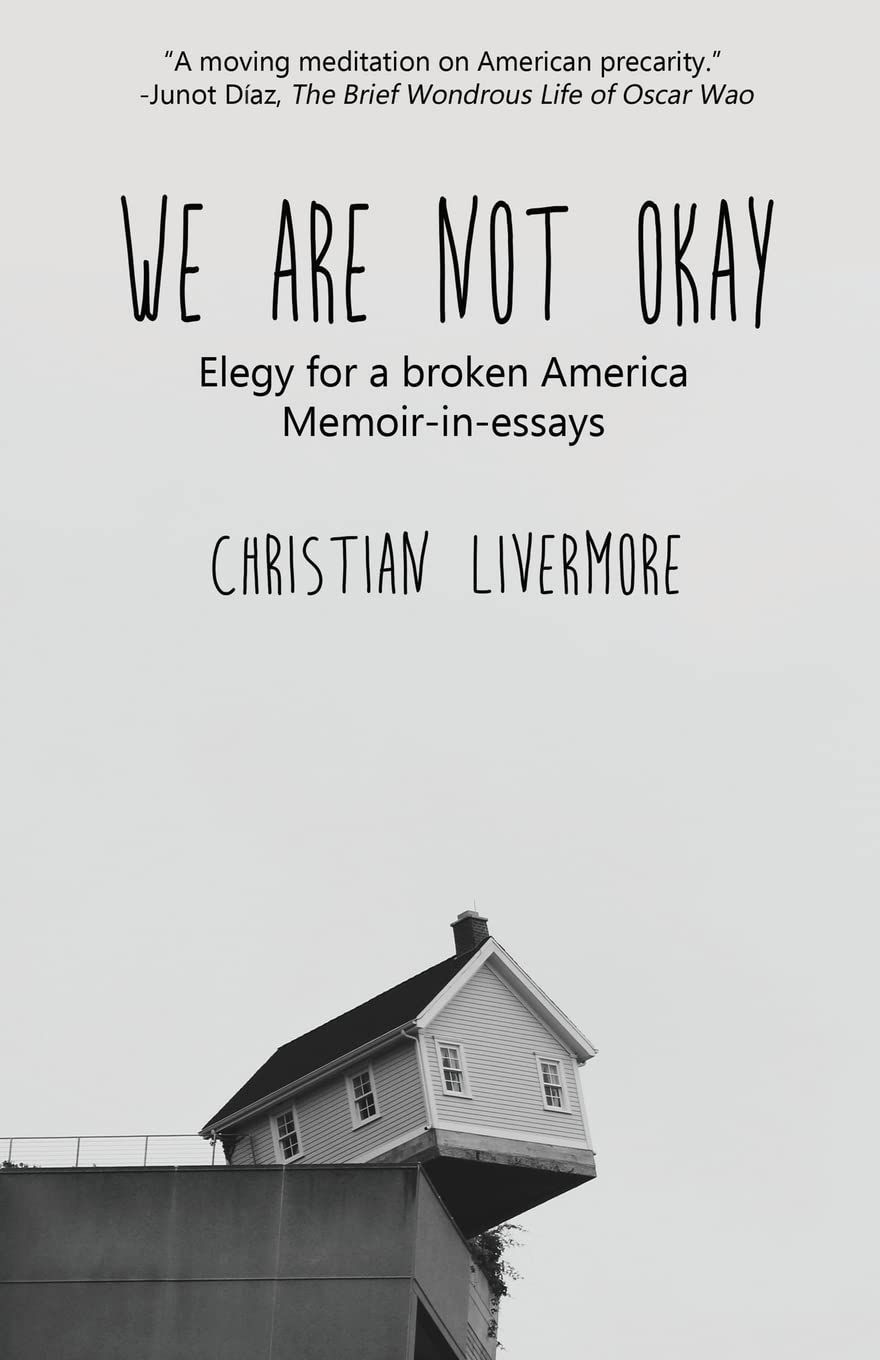

A new memoir by Christian Livermore, We Are Not Okay (Indie Blu(e) Publishing), brilliantly answers that question.

Livermore grew up in poverty, scrabbled her way out, and found that although she had left poverty, poverty had not left her. The book shows dozens of examples of poverty’s permanent damage. I’ll cite just four.

Easy frustration. “If I can’t get the lid off a jar, I feel like throwing the thing across the room…. I had already experienced so many normal life stressors by the time I was ten, I used up more than most people deal with in a lifetime.”

Poor impulse control. “If I get money, I spend it immediately, as though somebody might take it away from me. Because my whole childhood, people did. When I was nine years old, I had saved about $400 from working in my grandmother’s lunch shop…. My mother convinced me to open a joint bank account…. When I went to withdraw $20 a month later, the account had been cleaned out.”

Physical disintegration. “Then, one morning, while I was brushing my teeth, I felt something loose in my mouth. I thought it was a piece of the apple I had just eaten. My teeth are straight and white, because in America they put fluoride in the drinking water, but the severe gum disease from a childhood without adequate dental care and a lifetime of sporadic dental insurance has left me with little pockets between my teeth and gums where the enamel has eroded. I rinsed and spit, and something white clattered into the sink. I picked it up. It was not a piece of apple. It was a tooth.”

Shame. “That constant internal editing is part of the shame of poverty: what we permit people to know, what we will not admit even to ourselves, those things which are so shameful that we write them out of our own internal construction of ourselves. You don’t even always know that you’re doing it. You do it to survive the shame.”

Livermore also documents the external antipathy of American politics and society that cultivates this personal internal damage. “The idea that we are waste people is older than the country, and that knowledge that you are not valued by society wears you thin. In the housing project where I grew up, we were a bike ride away from the beach. But nobody I knew from the projects went there. Working class people did. But they had cars. There was no public transportation where I grew up. No bus to the beach from the projects…. You needed a car or a bicycle. Most people in the projects didn’t have a car…. Hardly anyone had a bike…. And even if they did, they couldn’t conceive of the energy it would take, biking to the beach.”

Poverty’s damage and America’s antipathy are the book’s subjects, but powerful as they are, they are not the most powerful aspect of the book. What makes this memoir ineffably important is way it conveys what it conveys.

If writing a book is a luxury of time to organize your thoughts, to choose perfect words, and to sort through readers’ possible inferences, Livermore’s We Are Not Okay takes poverty’s lack of time, patience, energy, food, transportation, health care, impulse control, and sense of belonging and translates it into a rhetoric that eats the traditional luxury of book-length prose.

Again and again, Livermore’s descriptions circle around an inability to express what they want to express. “How do I tell it? How do I tell it so you will understand? Not for sympathy, just so you will understand what it has done to us, growing up poor.”

Again and again, Livermore questions her own telling. “My first instinct was to write pointless anecdotes, but that is not true, and also not what I mean.” And, “The above is a story I wrote about something that really happened. But the truth is much different.”

Again and again, Livermore darts from past-tense exposition to present-tense narrative, from recent to distant-past anecdotes, and then explicates these shifts. “I often find myself writing in the present tense in this book. I think it is because these events are always ‘now.’ I will dream about them when I go to sleep tonight, and I will think about them when I wake up in the morning.”

Again and again, Livermore sprints among personal observation, secondary-source support, sophisticated analysis, and extended narrative in an overt, omnipresent struggle with the legacy of poverty to describe the legacy of poverty.

Livermore’s rhetoric of poverty is the antithesis of a luxuriously recounting in support of well-ordered themes or in service of a linear chronology. Rather, it is a jumpy striving for a truth that is by definition elusive.

For all its moving parts, Livermore’s prose is magnificently clear, startlingly direct. In that quality, it conveys yet another legacy of poverty: “[Poverty] has also left me all out of fucks. I am frustrated and out of patience, so I am ready to dispatch with certain normal life stressors very quickly. I usually do this with the phrase, ‘Let me explain something to you…’”

We are the beneficiaries of Livermore’s lack of fucks, of her rejecting the luxury of a rhetoric that presupposes an inherently disordered subject can be treated with writerly order, of her relentless and courageous and entertaining and upsetting display of the effects of poverty. To us, Christian Livermore is saying, “Let me explain something to you,” and we need to listen.

¤

LARB Contributor

Robert Fromberg is author of How to Walk with Steve (Latah Books, 2021), a memoir of autism, art, death, and punk rock. His prose has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Indiana Review, Colorado Review, and many other journals. He taught writing at Northwestern University for 17 years.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!