A Private Artifact of Public Madness: On Lora Lafayette’s “Possums Run Amok”

By Robert FrombergApril 1, 2022

Possums Run Amok by Lora Lafayette is a book, but it is not a Book.

Some books are Books. You can picture authors patiently and skillfully elaborating on scenes and analyses, searching for searing wording for the 7th revision of the 6th sentence in the 5th chapter. You can picture readers, on trains or in easy chairs or in bed, appreciating the grace brought forth by such care, right down to the pleasing-to-the-touch matte finish on the cover.

The core nature of such a Book, it seems to me, is public. It wants to be read. It cares about readers. It extends a hand to them. It brings them along on an eventful mutual journey.

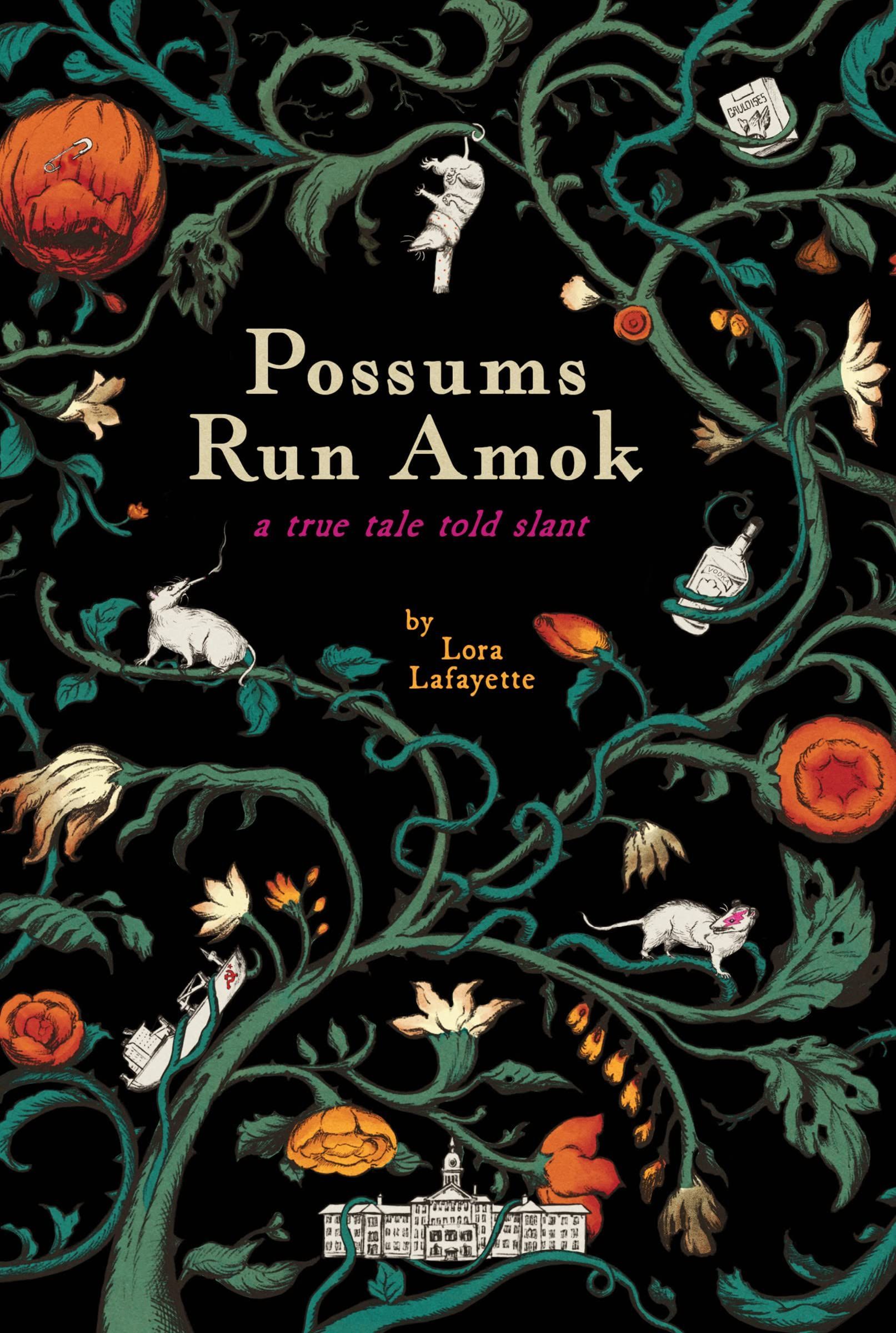

Other books are artifacts. Maybe you were fortunate enough to have acquired such a book in the form of a paper manuscript, three-hole punched and bound into a paper folder with a cover illustration drawn in colored pencils by the author, perhaps with other drawings decorating margins and blank spaces at the end of sections. If, on the other hand, such a work has been, against mighty odds, printed, bound, and published, the fact of its manufacture and sanctioned release is rapidly replaced by the false but very real memory of finding the hand-bound, author-illustrated version under a bridge, a little damp but still readable. When, having begun to read the manuscript, you immediately feel the guilt of reading something not intended for your eyes. But you keep reading.

The essential nature of such a work is private. Memoir, poetry cycle, or children’s adventure, it is borne and boundaried by what an author needs to say to survive and what the author is able to say without screaming. Presumably, such works exist in thousands, millions of places where people keep private things. Encountering one in public — whether under a bridge or on a bookstore shelf — feels like a miracle.

Possums Run Amok by Lora Lafayette is an artifact. It is an object that makes its way from author to reader un-intermediated, only by virtue of the reader having been on some path rarely trod and having looked down instead of straight ahead. (Possums Run Amok is being published by Mercuria Press, an imprint of Chin Music Press, in the spring of 2022. But let’s make a pact, you and I. Once we have offered our awe-filled thanks to this wise publisher, let us forget that anything has come between Lora Lafayette’s private words and us.)

I suppose that Possums Run Amok is a memoir. But it reads more like some combination of notebook, fable, and primal scream. It is the fastest book I have ever read. One can picture the author’s fingers blurrily tapping her keyboard, putting down her mostly generalized memories as quickly as she can type, never pausing long to occupy any one moment, scene, or sensation — author as sheepdog, chasing and nipping at a pack that outnumbers her absolutely.

Lafayette tears though 1970s pre-teen delinquency more outrageous and idiosyncratic than that of Sable Starr or Lori Maddox, to penniless following of non-penniless strangers in country after country, to multiple years of institutionalization. In Possoms Run Amok, Lafayette dashes through each stage, her younger self insisting on the joyous particularity of the horror that populates each of her days.

She and friends board a Russian ship docked near her home: “We wanted to stow away or defect, though we didn’t want to anger our parents…. We toyed with the idea of harboring one of them as a pet in this country, but none of them agreed…. I wasn’t prepared for the hole it would leave in my life when they departed…. I cursed Brezhnev for not invading…. All we had now were some copies of ‘Soviet Life,’ a paperback book of the Soviet constitution, the sweaters, a record of pop songs by Alla Pugacheva, some Belomorkanal brand papirosas, pins in the likeness of Lenin and the Soviet flag, and four cans of milk condensed with sugar.”

She and her friends experience the ephemerality of Portland: “Many times on routine trips to the grocery store, we would come across people felled and being kicked at by ambulance attendants. They were not always still alive. One man set a mountain of mangoes avalanching to the floor before him; I think he did die.”

She and a friend escape a rape attempt: “Yet she had no intention of sleeping with him and had suddenly, though momentarily, grown picky. He was irate. He pushed me away; Kay pushed him. She put her shoes on (the wrong way) and we ran up the laddery stairs, trying to find the way out … as we were leaving, Helg gave Kay a shirt she had coveted, a tee shirt with the stencil of an armadillo and the words ‘Evoludo No Gogo’—we were never positive what the Portuguese caption meant, but armadillos were Kay’s favorite creatures. The sailors all stood on the deck yelling after us that they loved us.”

The highs are so high that, as Lora’s friends leave and her physical and mental health deteriorate, their loss is like a punch in the sternum. However, the fierce breeziness is replaced by an equally forthright account of encroaching madness and confinement. “My only problem was that my thoughts were beginning to ache. But I was held in complete awe over the world, suddenly magnificent. I was seeing colorful light flashes everywhere. Colors and textures were more beautiful than structures, and structures overcame the sky.”

Later the beauty transforms into something else: “Objects began to threaten me in that they existed too strongly. An ashtray. A chair. A clock. They refused to be ignored and thrust themselves upon my consciousness.… I became alone in the world with each object, one by one. Their imposition was almost unbearable…. I knew the only way out was the complete destruction of myself.”

For whom does a writer write? Patricia Highsmith once said, “No writer would ever betray his secret life.” Yet when her 8000 pages of diaries and notebooks were found, they came with a note that invited them to be read. As much as Highsmith guarded her private thoughts, evidently she believed some important destination would only be reached when they joined with the public behavior that Highsmith’s intimates had witnessed and biographers recorded.

Possums Run Amok occupies an important position on an unsteady precipice between private and public. Its events and perceptions — plenty wild enough to warrant the veil of secrecy — carry the power of thoughts that impose themselves unbearably on a person’s private consciousness. Yet the real power of Possums Run Amok is not that it brings private events into public light, but that it allows the throb of one person’s privacy to reshape the privacy of anyone fortunate enough to read it.

¤

Robert Fromberg is author of the memoir How to Walk with Steve (Latah Books, 2021). His other prose has appeared in Indiana Review, Colorado Review, Bellingham Review, and other journals.

LARB Contributor

Robert Fromberg is author of How to Walk with Steve (Latah Books, 2021), a memoir of autism, art, death, and punk rock. His prose has appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Indiana Review, Colorado Review, and many other journals. He taught writing at Northwestern University for 17 years.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!