You Are Without Land, Without Love

Pericles Lewis ventures through Maya Jasanoff's "The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World."

By Pericles LewisDecember 24, 2017

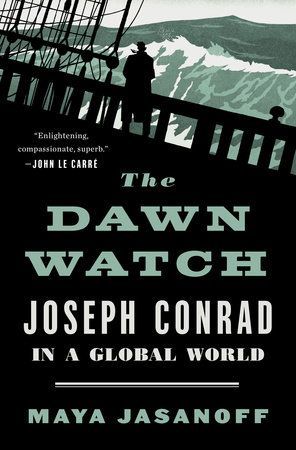

The Dawn Watch by Maya Jasanoff. Penguin Press. 400 pages.

IN “Passage to India,” the quintessentially American poet Walt Whitman celebrated the networks of commerce that were linking the world together at the end of the 19th century:

The earth to be spann’d, connected by net-work,

The people to become brothers and sisters,

The races, neighbors, to marry and be given in marriage,

The oceans to be cross’d, the distant brought near,

The lands to be welded together.

Aided by the invention of the steamship and the expansion of telegraphs and railways, the world economy entered a phase of globalization, celebrated here by Whitman in tones that prefigure the enthusiasm of today’s apostles of the information age. Maya Jasanoff quotes the poem at the beginning of her new book The Dawn Watch to illustrate the roots of globalization.

The races did not, however, live in the harmony envisioned by Whitman. During a period of relative peace within Europe and North America, the imperial powers extended their control of the rest of the world, and entered an age of empire that lasted until their competing desires for conquest exploded in World War I.

One novelist was in a unique position to chronicle 19th-century globalization and analyze the contradictions of imperialism. Born in what is today Ukraine, to Polish nationalists dedicated to the memory of a country that had been partitioned among three empires, Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski was welcomed into the world by a song from his patriot father:

Baby son, tell yourself,

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland — your Mother is in her grave.

More literally orphaned at the age of 11, and inspired by the novels of James Fenimore Cooper, Konrad Korzeniowski set out to sea before his 17th birthday. After personal disasters and (probably) a suicide attempt in Marseilles, he arrived in London when he was 20. There he joined the British Merchant Marine and sailed all over the world in service of British commerce.

Sixteen years later, as Joseph Conrad, he retired from the sea and began writing several of the greatest novels of modern English literature. In her brilliant book, Jasanoff explains how four of the best of these novels offer insights into globalization and imperialism that remain relevant today.

Jasanoff is an insightful and imaginative historian. Her earlier books told compelling stories of the lives of both powerful and obscure inhabitants of the British Empire in the 18th and 19th centuries, and won her many accolades (including the Windham-Campbell Literature Prize at Yale, where I teach). A genius of the archives, she brought together, in her award-winning Liberty’s Exiles, the stories of the losers of the American Revolution — the loyalists who left the newly founded United States and wound up in Canada, Jamaica, Sierra Leone, and throughout the empire. Likewise, her first book, Edge of Empire, introduces a rich cast of characters (British and French collectors of antiquities in India and Egypt), an empathetic understanding of how diverse communities interacted in the face of large historical forces, and a novelist’s skill at complex storytelling.

In The Dawn Watch, Jasanoff tells the life story of a novelist. The book comes in the form of a biography of Joseph Conrad, but in fact through Conrad she tells the story of a whole phase in world history. Conrad’s insights into his time have been recognized by earlier generations, notably by Hannah Arendt, who drew on his novels for her analysis of imperialism and racism in The Origins of Totalitarianism.

Recent generations of students and scholars may have been put off reading Conrad by his deliberate use of racist language and some of his stereotypical assumptions, which were famously exposed by Chinua Achebe. In reply to Achebe, Jasanoff quotes a young Barack Obama, who said of Heart of Darkness, “the book teaches me things […] [a]bout white people, I mean. See, the book’s not really about Africa. Or black people. It’s about the man who wrote it. The European. The American. A particular way of looking at the world.” And many postcolonial novelists, notably V. S. Naipaul, have admired Conrad for his mostly unsentimental analysis of race relations and his boundless curiosity about life at the edges of empire.

Boundless curiosity is also an attribute of Maya Jasanoff. In her earlier books, she pursued obscure characters through even more obscure archives. In The Dawn Watch, she travels in the footsteps of a famous writer. Other biographers have followed Conrad’s trail, notably Norman Sherry, who in the mid-20th century was able to interview many immediate relatives of people who had known the novelist. Sherry uncovered some of the “originals” of Conrad’s fictional characters. Nearly a century after his death, such pathways have closed, but Jasanoff found ways of reliving Conrad’s experiences, notably by traveling on a container ship from Hong Kong to Southampton, England, along routes followed by Conrad during his lifetime, and traveling by boat along the Congo River, the setting of Heart of Darkness, Conrad’s most famous and notorious work.

Jasanoff’s travels have given her an empathy and an understanding for Conrad, and also for the victims of imperialism, that breathe on every page of this magnificent book. She sees his plots in relation to the basic drama of his life, but sees that drama as itself reflective of broader historical events:

Conrad’s fiction usually turns on the rare moments when a person gets to make a critical choice. These are the moments when you can cheat fate — or seal it. You can stay on board a sinking ship or jump into a lifeboat. You can hurt someone with the truth or comfort them with a lie. You can protect a treasure or steal it. You can blow something up or turn the plotters in.

You could spend your whole life in the place where you were raised or you could leave and never come back.

Although written later, Conrad’s The Secret Agent tells the story of a terrorist plot in London in the 1880s, the decade when Conrad became a naturalized British subject. Jasanoff shows how the novel, a sort of rewriting of Dickens, reveals much about Conrad’s own life as a young man in London. She also suggests the relevance of Conrad’s analysis of 19th-century terrorism for our own day.

Conrad’s most technically adventurous novel, Lord Jim, tells the story of a young British sailor who does not live up to the code of the sea and who winds up traveling further and further east in an effort to escape from Western civilization. The story is related in a series of interviews and flashbacks that would later inspire Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Having spent so much time on shipboard, Jasanoff recognizes the storytelling technique (which goes all the way back to The Odyssey): this is “a narrative composed in sailor’s time.”

Citizen Kane was not the only major American film that retold a Conrad story in a different medium and setting. In the 1970s, when Francis Ford Coppola made Apocalypse Now, a film about the fate of US imperialism in Southeast Asia, he drew on Conrad’s African novel, Heart of Darkness, for his plot. Jasanoff shows that Conrad became a writer in Africa, where he worked on his first novel about Southeast Asia, Almayer’s Folly.

Conrad had spent most of his time as a sailor in Southeast Asia, and he later chronicled the intersection of a vast array of cultures in books like Almayer’s Folly and Lord Jim. Jasanoff retells the story of Conrad’s travels in the region, but she offers a new interpretation, pointing out that the ship he served on as first mate was active in the (illegal) slave trade, and tracing the presence of slavery in his portrayal of Malay society.

This interchange between the two regions forms part of the history of empire and suggests how racism and globalization intertwined. Jasanoff investigates the moral ambiguities of Heart of Darkness with great sensitivity and awareness both of Conrad’s biases and of the horrors he witnessed. She shows how Conrad exposed the horrors of the supposed Belgian civilizing mission in the Congo, but also analyzes his reluctance to get involved in political crusades, which she attributes to his reaction against the suffering caused by his parents’ idealism.

Perhaps Conrad’s greatest novel, and his most demanding, is about a region he never saw at first hand. Nostromo describes a revolution in a fictional Latin American country, Costaguana. By reconstructing Conrad’s process of writing the novel, and drawing on contemporary press accounts of the 1903 revolution in Panama, Jasanoff shows how Conrad evolved his critique of US power in Latin America; she sees him as a clear-sighted observer of the future of the Western hemisphere, despite the fact that he had only seen the Latin American coast briefly from onboard ship. Costaguana was therefore fictional, invented, in a way that the settings of his earlier novels were not, but Conrad was a sufficiently perspicacious reader of the newspapers and of human nature to offer a telling interpretation of current events, as well as a rich invented world of great depth and sympathy.

Most novelists tell us about an event and then describe its consequences. Conrad often reversed this chronology: in his best novels, he describes impressions and experiences and then spends pages analyzing their causes. The result is a kind of epistemological disorientation in which the reader continually gathers clues almost as in a mystery novel. Unlike in most mystery novels, however, the answer to Conrad’s riddles is not a simple “whodunnit.” Often, as in Lord Jim, he describes experiences precisely to show that the mystery is insoluble. As Jasanoff puts it in speaking of Conrad’s English alter ego, the narrator of both Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim, “Marlow was constantly seeing things but only later managing to figure out what they meant.”

In what is probably the best book ever written on Conrad, Conrad in the Nineteenth Century, the critic Ian Watt influentially described this method as “delayed decoding.” Maya Jasanoff has taken Conrad’s technique as her own. Frequently she tells us a wonderful story out of Conrad’s life, lovingly reconstructed from his memoirs and letters, only to explain a few pages later: “Yet almost none of what Conrad said lines up with other records.” A critic and historian with the virtuosity of a latter-day Sherlock Holmes, Jasanoff then goes on to retell the story based on her own findings. Through it all, she shows how Conrad’s story is part of a broader history — the history of globalization and empire — world history. This is the best book on Conrad since Watt’s. Maya Jasanoff has given us a Conrad for the 21st century.

¤

LARB Contributor

Pericles Lewis, professor of Comparative Literature, serves as vice president for Global Strategy and Deputy Provost for International Affairs at Yale University. From 2012 to 2017, he was the founding president of Yale-NUS College, a collaboration between Yale and the National University of Singapore. The author or editor of six books, he was also the founding editor of Yale’s Modernism Lab, an early digital humanities project. He has written for a number of academic journals as well as the Chronicle of Higher Education, Harvard International Review, Los Angeles Review of Books, and Times Higher Education.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Darkness Nearly Beyond Words: On Elizabeth Kostova’s “The Shadow Land”

Robert Zaretsky plumbs the depths of “The Shadow Land” by Elizabeth Kostova.

An Interview with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Nanda Dyssou talks to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o about writing in native languages, living in exile, and his hope for Africa.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!