Workmanlike Surrealism: On Alex Danchev’s “Magritte: A Life”

Alex Danchev’s final book is a sparkling biography of a prolific, popular artist.

By Peter PlagensJanuary 21, 2022

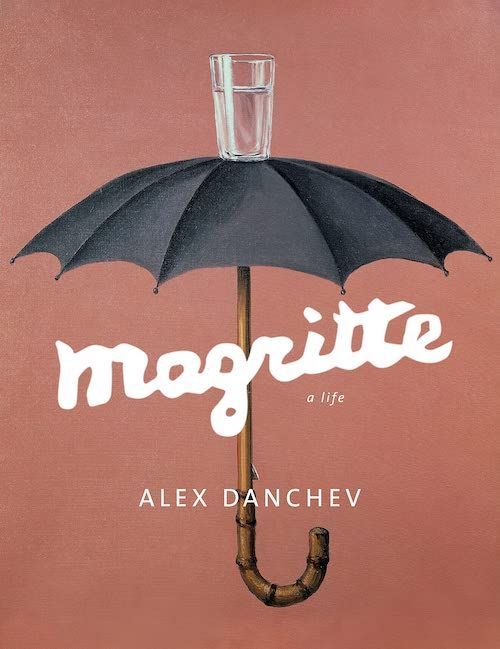

Magritte: A Life by Alex Danchev. Pantheon. 480 pages.

I always try to make sure that the actual painting isn’t noticed, that it is as little visible as possible. I work rather like the sort of writer who tries to find the simplest tone, who eschews all stylistic effects, so that the only thing the reader is able to see in his work is the idea he was trying to express. So the act of painting is hidden.

— René Magritte (1898–1967)

¤

IF THERE IS such a thing as a down-to-earth, meat-and-potatoes surrealism (or, since we’re talking about a Belgian artist, un surréalisme moules-et-frites), René Magritte is its paragon. With his wife Georgette almost always nearby, Magritte ate, met friends, and rolled up the rug to paint in the dining room of his modest house in suburban Brussels. Early on, in 1929, he painted La trahison des images (The Treachery of Images) — that infamous smoker’s pipe with the caption “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” (This is not a pipe.) — one of the most reproduced images in the history of art. Was Magritte avant-garde? Late in the game, the artist himself summed it up: “In life as in my painting, I am also traditionalist, even reactionary.” Of course, it’s not quite that simple, and Alex Danchev, in his rock-solid new biography, Magritte: A Life, which was completed after his death by Sarah Whitfield, reminds us of the complications.

Magritte was born in Lessines, a small town near Brussels, to an irreligious bounder of a father (“[H]e got us to spit on the cross in front of maman”) and a terminally unhappy mother who committed suicide by drowning. Magritte was a bad boy. He cut school and had — as mentioned in one of Danchev’s many felicitous phrasings — “a drip feed of [the fictional villain] Fantômas and company throughout his teens.” At the age of about 11, he began what would be his lifelong fascination with pornography and became forever conspicuously horny; his friend Charles Alexandre recounted: “Magritte was painting a nude young girl. In our presence he finished the canvas, and then disappeared into the next room with his model, telling us solemnly: ‘And now, gentlemen, the artist is going to screw the model.’” If this sounds like god-awful male chauvinism, it is, but one might plead, as in traffic court, “guilty with an explanation.” The early years of the 20th century weren’t exactly the epitome of gender enlightenment, and the surrealists (a few women artists notwithstanding) were a boys’ club — some might say a group of sniggering adolescents who saw Sigmund Freud as giving them whatever sexual (and sexist) license they needed.

In Georgette (née Berger), Magritte found a counterweight. He first met her at a fair when she was 12, he 14; seven years later, they re-met at the Brussels Botanical Gardens and straightaway fell in love. For Magritte, “her body [was] both a temple and a template”; he worshipped her, but at the same time he used her — artistically, in painting after painting, and less honorably in practical jokes (he once locked her in a coal bunker just for the hell of it). There’s dubious speculation that during their marriage Magritte had an affair with “a beautiful surrealist groupie,” but, on the other hand, it’s incontrovertible that Georgette had a long and serious affair with Paul Colinet, a close friend of René’s. Georgette eventually called it off and “reinstated Magritte as the apple of her eye.” For his part, as a kind of revenge, Magritte ramped up his frequenting of prostitutes.

Magritte’s life as a fine artist wasn’t uncompromised, either. In his early 20s, he found a job as a wallpaper designer and continued to do commercial work through most of his life. He set up a separate shed — “Studio Dongo” — for his non-beaux-arts products. A “model of professionalism” in that regard, Magritte created posters for Alfa Romeo and designed the “Skybird” logo for Belgium’s now-defunct national airline, Sabena — which, he said, “put a good deal of butter on my spinach.”

On the downside, Magritte was also a forger; he concocted a Hobbema, faked Titians, and even had the chutzpah to combine elements of extant paintings to make his own hybrid Titian. (A question I can’t answer is how such an anti-elegant painter as Magritte could forge a convincing Titian.) Magritte also cranked out ersatz modern pictures. The under-the-counter dealer Marcel Mariën said that, between 1942 and 1946 (when Belgium was occupied), “I sold a significant number of drawings and paintings attributed chiefly to Picasso, Braque, and Chirico, all made by Magritte.” The forger justified his fraud by saying that the fakes gave satisfaction to the unsuspecting buyer while providing an income for a hard-pressed artist. In a clever surrealist rationalization, Magritte added that the forgeries were a kind of time bomb whose inevitable exposure would mock the current social order.

¤

Almost from the start, surrealism was bifurcated. In one faction were those more directly committed to social action, who saw the style as that aforementioned time bomb. In the other were the true believers in the Freudian unconscious. The direct expression of the latter wasn’t for Magritte. “Psychic automatism,” Danchev writes, “was enough to make Magritte see red.” The disregard was mutual. French surrealists — mostly purveyors of the unconscious — thought the Belgians bumpkins. A popular joke in France asked the difference between a potato and a Belgian. Punchline: A potato is cultivated.

The poet/provocateur André Breton, the self-appointed “pope” of surrealism (“nothing if not a moralist, with a fine line in disdain,” Danchev notes), actually excommunicated artists who didn’t meet his standards and decreed that “[t]here is no use being alive if one must work.” The Belgians to the contrary had jobs. Magritte, who discovered surrealism around 1925 and two years later began a Paris sojourn that lasted three years, fell out of favor with Breton on December 14, 1929. Breton scolded Georgette for wearing a cross to a surrealist party; she left, and Magritte followed. But before he finally quit Paris in the summer of 1930, Magritte and Georgette accepted an invitation from Salvador Dalí — whom Magritte somehow rather liked — to come to Catalonia for a month. The “two bad boys of surrealism — Dalí the deviant, Magritte the derisive — painted side by side, almost,” Danchev tells us, “or at any rate studio by studio.”

Magritte’s surrealist epiphany had been a 1923 encounter with a reproduction of Le Chant d’amour (The Song of Love), a 1914 painting by Giorgio de Chirico (yes, the same de Chirico whose works Magritte later faked). Danchev writes, “He was overwhelmed. Magritte’s discovery of de Chirico (and thereby himself) is one of the great mythmaking moments of modernism.” The discovery of the artist whom Magritte would say was his one and only master had, however, the effect of making him stop painting. Not for long, though: for a period in 1927, he averaged three completed paintings a week, and during his stay in Paris, he whipped out just under 300 paintings, about a quarter of his whole oeuvre. Magritte himself boasted that he was “capable of doing sixty paintings in a single year, some of them very large.” Such productivity is startling. We might not be surprised by this if Magritte were a not-too-picky abstract expressionist or a Jeff Koons with a veritable factory full of assistants. But Magritte was solitary, workmanlike, and accurate. His blue skies glow, his rocks (levitating or not) weigh convincing tons, his human figures are, if not masterful, at least credible, and nobody renders a bowler hat more engagingly. Certainly, a Magritte boulder is a lot scarier than a Dalí tiger.

That Belgian competence has, however, its comings and goings. Magritte’s god-awful “sunlit” period of the mid-1940s, which Danchev describes as “a pseudo-impressionist style reminiscent of late Renoir, run amok,” might be excused as an attempt to counter the darkness of the Nazi occupation, but it’s still painful to look at. The brief “vache” period (the word means cow but connotes stupidity) is worthwhile only as flash-forward toward, say, Peter Saul and the “Bad Painting” of the 1970s. Some of the best — and, non-contradictorily, most popular — Magritte paintings come from the 1950s and early 1960s: L’empire des lumières (The Empire of Light — his day/night contradiction that comes in many versions) or Les valeurs personnelles (Personal Values — a roomful of gigantized objects).

With, finally, financial success (which came largely through the American art dealer Alexander Iolas), Magritte could travel abroad (“something he had always done his best to avoid”) and build a fine house. Well, almost. Magritte bought some land in the upscale Brussels suburb of Uccle, but the cost of the prospective house’s details (one senses Georgette calling in debts here) led him merely to purchase the house he was renting nearby, in the more modest commune of Schaerbeek.

However pedestrian his residence, everything else seemed to tumble grandly Magritte’s way: retrospectives in Brussels, Dallas, Houston, Minneapolis, and, in 1965, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Not only was Magritte an influence on scores of contemporary artists (his art is so tempting to riff upon), the likes of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg bought works by him. And with Alex Danchev’s Magritte: A Life, René Magritte gets a biography he deserves — thorough, with delicious bits of writing: e.g., “Magritte bragged that he arranged for Mesens to lose his virginity that same night, with a barmaid who performed her duties with the practiced automatism of a switchboard operator.”

On August 15, 1967, Magritte entered a hospital for a gallbladder operation, but the doctors concluded that surgery wasn’t possible. Georgette noted that René went to the hospital in a car but came home in an ambulance. He went right to bed and never woke up. (Georgette, the keeper of the flame, lived on until 1986.) Magritte is buried in Schaerbeek under a slab with no epitaph. His workmanlike irreverence might have been captured on a tombstone, however, had someone carved into it his sardonic remark made after a hurried visit to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, Italy: “I saw Botticelli’s Primavera, it’s not bad, but it’s better as a postcard.” The tombstone, of course, would be a painted one.

¤

Peter Plagens is a painter and writer who lives in Connecticut.

LARB Contributor

Peter Plagens is a painter and writer who lives in Connecticut. He is represented by Nancy Hoffman Gallery and the Texas Gallery. His book on Bruce Nauman was published by Phaidon in 2014.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Signs of Life in a Surreal World: A Conversation with Charlotte Mandell on Breton and Soupault’s “The Magnetic Fields”

Paul Maziar talks with Charlotte Mandell about her new translation of Breton and Soupault’s “The Magnetic Fields.”

The Surreal Sources of “Lolita”: Nabokov and Dalí

Delia Ungureanu uncovers the hidden surrealist subtext of Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!