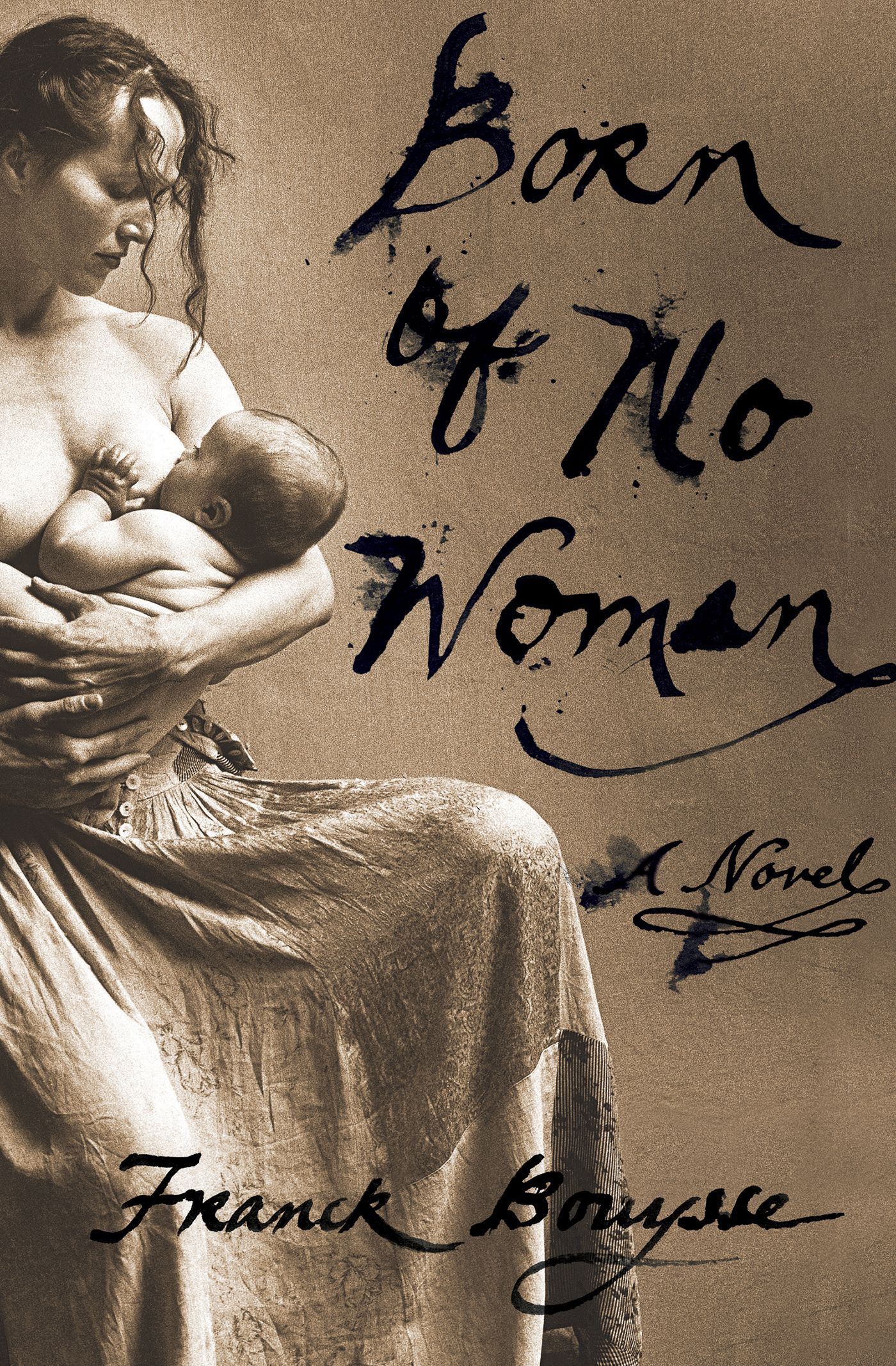

Born Of No Woman by Franck Bouysse. Other Press. 368 pages.

I AVERAGE 1,000 translated words a day. Yesterday, for example, I translated 1,000 words of a French novel, none of which I remember because, also yesterday, I lost a baby, and grief is bellowing in my ears and billowing in my gut and coursing through my veins it is bottomless it will never end I will never get over this. This grief won’t abate, not in a few days or a few weeks or a few months, so I translate another 1,000 words, and another and another.

I don’t remember what I translated, but what it might have been, if art and life happened to seamlessly coincide, is a passage about a woman grieving her lost daughter, not a nine-week-old fetus like mine, but a 15-year-old girl named Rose who is sold into servitude somewhere in 19th-century rural France without her mother’s knowledge:

[The mother] remembered that when she was a child, her father had taught her to recognize birds by their song. Her heart began to bleed as she walked and they went invisible in the foliage. The winged creatures accompanied her nevertheless, still invisible, for at no moment did she raise her head, or even consider it—too heavy, too unbearably heavy.

The novel I’m translating is called Born of No Woman, a harrowing gothic tale written by Franck Bouysse, which became an unexpected bestseller in France upon its 2019 release. In French, the novel numbers 86,600 words, which, once I complete my translation, will likely be five to 10 percent shorter, not because I’m taking shortcuts or liberties (though I’ll take a few of the latter) but because English is so much more succinct. Where French takes its time, reveling in redundancy and repetition, English gets right to it—a sucker punch of a language.

Some mothers who miscarry—in French, the term is longer but just as admonitory: fausse couche, a false/faulty/incorrect birth—call their fetuses angel babies. They give them names and birthdays and celebrate them as if they had been born, had lived a life, however brief. I’m not a God-fearing woman and I don’t believe in angels, so I don’t call mine an angel baby, but I do call it a she. I call it a she, a sister to my three-year-old son, and this even though I know it/she was barely sentient, almost nothing at all. Except she was everything at all. For nine weeks, she was everything at all.

There is little in Born of No Woman that resembles my life, no bond between the novel and me beyond that of translator and translation. It is not what I would typically buy in a bookstore (its plot of trauma and betrayal too grim). Still, the novel is essentially about motherhood—the gaining and losing therein—and I, one could argue, am essentially a mother. “Essentially” in the sense of above all else. The novel, which is the 10th that I’ve translated from French, is also the first that I’ve taken on because of a single, perfect sentence, the last one in this passage (in my translation):

Never in his life had [the father] seen a bird go backwards. It was only earthly animals that chose to do so, as if mere contact with the ground made them question whether there was any point to tearing themselves away from it between one step and the next. And still, each morning he rekindled the fire that had gone out the night before, all that was expected of a man done, because he knew deep down that men alone are earthly animals, and women and children, birds.

Perhaps this is what I was translating the day I lost the baby. Except: I would have remembered. I would have remembered because I got stuck and translated the passage nine or 10 times. Earthly animals. Earthly creatures. Terrestrial creatures. Land beings. Land things. Landings. Endings.

Though I do remember. I was more determined than usual, anxious even, to find the right translation. And this because the terms gleaming and unwelcome in the forefront of my mind—nonviable, spontaneous, blighted—were so unapologetically bold and cold that I thought, I must have thought, if I could just find the words to best describe one image—a bird (or a few) forever flying forward—words that would slide into an open slot with a satisfying click, that, at least, would be something. “Something,” here, in the sense of respite.

¤

Because I am bilingual, one might expect my breadth of expression to be greater, my choices vaster. And yet, despite this linguistic profusion, what terrible dearth! I am not alone in my inability to vocalize a loss. Nor am I the first, last, only woman to have a miscarriage. But what many people don’t know, and what I find myself wanting to tell them, everyone, is this: there is no miscarriage as terrible as your own.

Perhaps I didn’t translate that passage about earthly animals, or the one about the mother walking through a forest intending to kill herself until, startled by the gentle brush of a swallow flying past, she turns back, to tend to her other three daughters. Perhaps these associations are only coming later, in an attempt to neatly frame an event quietly leaking from its sterile packaging. But I must have translated some passage, 1,000 words more or less, to compensate for my inability to find my own.

¤

People are uncomfortable with grief. They don’t know where to put their eyes, their hands. If you say it on Twitter, does that mean you’re okay? If you say nothing, does that mean you’re okay? If you say it’s fine it probably would have had birth defects, does that mean you’re okay? No, no, no.

People are so uncomfortable with my grief that I tell no one, apart from my husband, when I get pregnant again two months after the miscarriage and when, a few weeks after that, I lose it (or her or him or they). A chemical pregnancy. The French term is the same, a nasty cluster of consonants, and just as reductive: grossesse chimique. And yet I can find no word, no neat phrase, in either language I speak that can adequately express this hollow that is also a heaviness, these nesting dolls of grief, the steady darkening of gray to black.

There’s another passage in Born of No Woman that takes me multiple tries as well—a syntactically challenging paragraph about mold growing in a pitcher of homemade wine, though it’s really about a mother who doesn’t know what has become of her daughter but rightly fears the worst. Translation: The steady darkening of gray to black.

The mother floated, like mold in the wine pitcher. She began to slowly thicken on the wine’s surface, slowly and stubbornly covering up a memory of lips, and also the lips themselves, imprisoned beneath this unstable crust that could have served to make the best of vinegars and yet that nobody would use for such a purpose.

I need to get this right because the scene is pivotal to the mother character, who, for all her importance, is only ever referred to as “she.” I need to get this right because my lower abdomen is still cramping and my maxi pad is stained crimson and grief may be an elusive beast, meaning that it won’t be tamed but surely it can be named.

For that opening sentence, I settle on “floated,” though the French instead uses se déposer, which can be translated as “to be deposited” or “to settle” or (at a stretch) “to leave oneself behind.”

¤

A close friend lost her baby two days after I did. No, let me start again, to get a sense of how the bold-cold words sound now. A close friend’s fetus was determined to be unviable two days after mine was, and we each carried our unviable fetuses for an additional 10 days before medically triggering their expulsions. My friend did not name her baby or guess its gender; she was sad but composed, sad but not despairing, at least that’s how it seemed to me through our WhatsApp exchanges and one brief six-feet-apart meeting. I thought: She’s been trying for one month, and me for 18—how can her grief possibly weigh as heavily as mine? This was a tiny thought, fleeting and shameful. I’m still ashamed.

We met in person that one time, my car parked by her apartment with the engine running, so I could give her a care package. A sorry-you-miscarried gift. She didn’t bring me anything, and at the time, I was wounded, as if CVS-bought sweets and a charcoal face mask were a reliable indicator of friendship. I silently reproached her for being too cavalier, too “that’s life” (though she’s French, so what she actually said was “c’est la vie”). What I wanted, I later realized, was for her to say: I see how sad you are, I’m that sad too, let’s be sad together, no one else has ever been as sad as us.

¤

In Born of No Woman, the lost daughter, upon learning that her mother and sisters have abandoned their family farm, recalls a stone with her initials engraved on it:

Nothing but a rock covered with moss, that the earth will swallow sooner or later, or that someone will dig up one day and use for a piece of wall. […] It’s terrible to think there’s no reminder of me out there, apart from those initials in the stone. In truth, I exist for no one.

A few days after the first miscarriage, I decided that my son and I would paint some stones. Perhaps I had already translated the passage above, perhaps not. We pilfered from a rock garden at the nearby middle school and settled in at the kitchen table. The idea was ladybugs: red wings, black spots. He quickly veered into cubism; I painted a flower. I’ve drawn this flower many times before, on textbooks and notepads and those magazine subscription cards that litter waiting rooms. It’s easy enough to execute, five broad strokes for the petals, another two for the stem and leaf.

I held a ceremony with my flower stone, with my husband and son, in a wooded national park a five-minute drive from our home. It was early May, but the forest cover cast a chill. We stopped beside a brook, where I squatted as my son cheerfully gathered pebbles and sticks. I was crying, I was clutching my stone, I whispered words meant to be healing and definitive, goodbye, c’est la vie, I love you, as I gently placed it in the water.

By now the stone will have been carried far on its nautical voyage, or long since buried in silt. Though maybe, if someone was looking, if someone knew to look, they might see faded strokes of pink and blue and green against the beige. But who would think to look for a stone that is not really a stone but a reminder, except for the people who know it’s there, meaning me and my husband and my son, and now you?

¤

The mother settled into the pitcher. The mother was deposited. The mother left herself behind. The mother floated. The mother is floating. The mother is floating away.

I worry that it’s unfair to appropriate a novel in this way, to inscribe the circumstances of my life onto a painstakingly written book that has nothing to do with me. Or simply unprofessional. But are there that many other ways, once grief has grabbed hold of you, to seek solace, apart from identifying a similar sadness somewhere, anywhere? From finding parallels and borrowing words for a thing you can’t or won’t name? Here, listen closely, this is how I will say I’m hurting. And here, here’s how I will say I love (still, more, never again).

In my case, solace comes from a novel written in French that speaks of women and children as birds. My solace comes from turning 86,600 words into the same but different words, often instinctively, sometimes mechanically, against the blue glare of a screen, the smooth feel of keys beneath my fingers, a comforting clacking sound, for as long as I can go, keep typing, a head too heavy, mold in a pitcher, a forgotten stone, control-S, and this until the grief abates.

Because of course my grief abated. For yesterday isn’t actually yesterday, yesterday is nearly three years ago. I can write this now, I can only write this now, because after the miscarriage, and after the chemical pregnancy, there was a viable pregnancy. “Viable” meaning a fetus carried to full term; “viable” meaning a thing with feathers; “viable” meaning the warm and gentle filling-in of an empty place.

Children born after a miscarriage are sometimes called rainbow babies, a term that, though I appreciate its sentiment and necessity, has always sounded cloying to my ear, and the French equivalent—the neologism bébés arc-en-ciel—forced. And so, I never refer to my baby as a rainbow baby. I do, however, unconsciously, give her a name that means light. Lucia, from the Latin lux. Or, as my dear French friend points out, like luciole, which can be translated as firefly or lightning bug or (at a stretch) a winged creature bearing light.

I promise I haven’t forgotten them, though. The other mothers, the ones still trying. I know how sad they are, that no one else has ever been as sad as them; if it will help (it probably won’t), I’ll be sad with you.

¤

Two-thirds of the way into Born of No Woman, the lost daughter becomes a mother. The pregnancy is unwanted and the child unwelcome, until his arrival, when everything inevitably changes. I won’t give away the ending except to say that the black lightens to gray.

This book gave me almost 87,000 words, which I translated into 82,000. Words for loss and rage, words for the grief whose age-mottled hands were firmly tightening around my throat, but also, especially, for the after-grief, for the forever flying forward. Still now, when I hold my daughter, when I hold my son, in the rare moments of quiet when I’m able to hold them both, I realize: yes, yes, yes, these are winged creatures not made to stay on this earth. I think to myself: our collective buoyancy is such that we may just take flight.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lara Vergnaud is a writer and literary translator living in southern France. You can find her work here and follow her on Twitter @laravergnaud.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Grief Is Never Finished: A Conversation with María José Ferrada

The award-winning children’s author discusses her first adult novel about the legacy of the disappeared in Chile.

Anatomy of Grief: A Conversation with Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Sarah Herrington in conversation with Rachel Eliza Griffiths about her new poetry collection, “Seeing the Body.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!