Why We Love Disaster Films

Jon Catlin examines critical disaster studies through a series of books, the problematic cornerstone being David Thomson’s “Disaster Mon Amour.”

By Jonathon CatlinMay 26, 2022

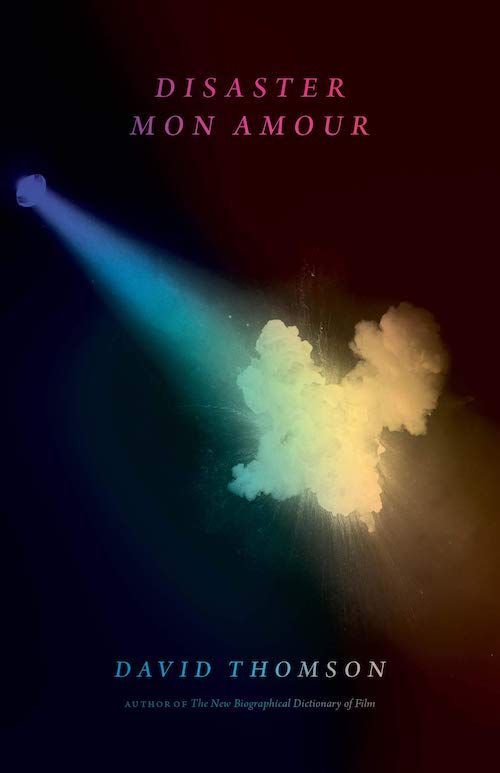

Disaster Mon Amour by David Thomson. Yale University Press. 224 pages.

WHAT LIES BEHIND our romance with disaster? So asks the prolific British-born film critic David Thomson in his latest book, Disaster Mon Amour (Yale University Press, 2022), whose title plays on Alain Resnais and Marguerite Duras’s 1959 classic Hiroshima mon amour. Thomson’s answer plays upon the ambivalence of the term disaster (or catastrophe, the subject of my own work): it can mean anything from events threatening to end life on earth to trivial blunders like ripping your pants on a date or scandals besetting the British royals in “the centuries-long disaster of the monarchy.” Disaster comes from the Latin for “ill-starred” or “unlucky” event, but it is also something we evidently love to watch — when it happens to somebody else on screen.

Disaster Mon Amour interweaves film criticism with Thomson’s own “journal of the plague year.” He muses, looking out from the ripe age of 79 at the time of writing,

I’ve been in a 6.9 [earthquake], and here I am in the moment of Covid-19. Yet I am calling this book Disaster Mon Amour because the fearsome possibilities cannot escape some irony or romance that may amount to beauty. It’s as if in crisis we can feel history rolling over us like a gorgeous wave.

Our attitude toward disaster, Thomson writes, is polarized between terror and attraction: “[W]e contemplate disaster more and more, as if entranced, while having mixed feelings about it.” Disaster can be terrifying, of course, but also unexpected, funny, and even “delightful,” as we see in Don’t Look Now (1973), an art horror film that braids “amour and disaster together.” Disaster has a Janus face, showing us alternately “its poetry as well as its doom.” Ultimately, it seems, “[w]e are not quite as terrified of disaster as we say.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Thomson was lucky to already have a face mask on hand from living amid the smoke of California wildfires. COVID served as a “rehearsal” for climate crisis, but the reverse is also true. Disasters, as we know all too well, keep coming. So, too, do disaster films — the category is “a genre by now.” When Thomson saw San Andreas (2015) in San Francisco, the audience let out “merry whoops and cheers” as Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson heroically rescues his family; his “foolish” closing line, “Now, we rebuild,” exemplifies American desperation for finding hope amid calamity. Thomson identifies the filmmakers’ goal to create “a spectacle of devastation with cozy human interest.” In these respects, San Andreas reprises the “blithe” 1936 film San Francisco, centered on the famous 1906 quake. Instead of genuine reflection on disaster, both movies offer redemptive, Hollywoodized affronts to the “unhealed wounding” Thomson sees in their bleak, postapocalyptic foil, The Road (2009), based on Cormac McCarthy’s 2006 novel. But even in 1936, the real disaster, the Great Depression, “was seldom a topic for movies.” Disaster was too real and needed to be confined to the fantasy of King Kong running amok. In later decades, “allegedly lifelike renderings of physical destruction seemed a relief from the steady television reportage of Vietnam, where damage was commonplace, not special.” Disaster films can be a mirror, but more often, they are a diversion.

Thomson’s narrative adopts a deliberately jarring style, skipping between movies and scenes like a filmic montage, signaled by the word “CUT.” After all, “a crucial rhythm in disaster is the unexpected.” An early chapter shifts between the grand political massacres of Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) and comic disasters like the short film The Music Box (1932), in which two amateurs delivering a piano send it tumbling down a huge set of steps. To Thomson, the latter reveals that even “if we were there on the steps we wouldn’t think to help or intervene because that would mean stopping the disaster we anticipate and adore.”

Thomson finds a graphic match in Battleship Potemkin when, in the middle of a crowd gathered in solidarity with mutinying, revolutionary sailors, a mother is shot by Tsarist troops and the carriage holding her baby slowly tumbles down the Odessa Steps, sustaining “a deep-seated tension between chaos and control.” Thomson’s thesis is simple: “[W]e love disaster if it happens to others” and “it is vital that we are watching their bad luck.” We especially love fictional disasters when they serve as protection against real ones we are observing and experiencing in our own time. But this elegant thesis flattens out the striking differences between Thomson’s chosen disaster films. Battleship Potemkin was a breakthrough in political cinema and was widely censored in its time because of its perceived power to move spectators to action. This distinction is erased when Thomson slots it in between frivolous and escapist blockbusters, action movies that pacify, demanding no action whatsoever from their target viewership.

Thomson’s deep knowledge of cinema history lends breadth and fluency to the book’s first few chapters. But as the book goes on, Thomson’s daily analyses of the pandemic years grow tired. His sometimes embarrassing political musings refer to Trump as “the Monster” and reflect garden-variety liberal catastrophism about the Bad Orange Man. Floundering to respond to the pandemic crisis, Trump is, to Thomson, at once “childish” and “evil,” not just “a very bad man,” but one with “extra menace.” This “infant president,” Thomson writes, speaks “with the gravitas of repressed belches” out of his “puffed-up face with its pinched-anus mouth.”

On the flip side, Thomson laughably valorizes MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow as “the Joan of Arc of modern television” with her “unquestioned air of courage.” At one point, he bizarrely imagines himself as a “sportsman” who finds himself in the same woods as “the Monster” and is “drawn to dispose of him.” Of course, Trump was “a vain, tasteless, dishonest disaster,” and the Trump era (as before it) was disastrous; but Thomson’s myopic view presents this as a result of Trump alone. As left intellectuals like Corey Robin and Samuel Moyn have stressed, many long-standing social ills are obscured when the hysterical liberal commentariat claims, like Thomson, that Trump “is the worst personal disaster this country has ever faced.” Trump had little to do with the authorities one day unceremoniously clearing away a tent occupied by an unhoused person in front of Thomson’s San Francisco home; NIMBY liberals did that. Trump gave permission to the worst impulses in American society, but he didn’t create them.

Despite the weakness of Thomson’s commentary on real, contemporary disasters, his book brings to life what is by now a commonplace of media theory and criticism: that film reflects life, but life also reflects film. Disasters are socially mediated and staged, to the extent that their representation shapes how we experience and remember them. One need only think of Slavoj Žižek’s argument that the highly mediatized 9/11 attacks and their aftermath followed the script of a Hollywood disaster film. Thomson recalls that on that fateful morning, watching footage of the second plane hit the towers, his young son asked, “What movie this was from?”

The nascent field of “critical disaster studies,” according to a recent volume by that name (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022), takes this insight about the social construction of disasters even further. Editors Jacob A. C. Remes and Andy Horowitz contend that “there is no such thing as a disaster” as such, because disaster requires “an act of interpretation.” The notion of disaster itself, then, is an analytical conceit or interpretive fiction, and this matters because if disasters are inherently “shaped by contests over power,” they are not amenable to purely technocratic solutions.

When speaking of disaster henceforth, we cannot escape the ensuing political questions this volume interrogates: “Whose deaths ought to inspire outrage, and whose resignation? What kinds of suffering are a legitimate cost of the status quo, and what kinds of suffering ought to suggest that the status quo itself is illegitimate?” Contributor Scott Knowles’s related concept of “slow disaster” urges us to see disasters like Hurricanes Katrina and Maria as long-term failures of investment, deferred infrastructure maintenance, and short-sighted electoral politics, not to mention the slowest disaster of all: in Thomson’s apt words, “The underlying pandemic in the United States — so pervasive it was fanciful to think of treating it — was poverty.”

As Knowles stressed in his 2018 polemic, “What Trump Doesn’t Get About Disasters,” to which the avid Times reader Thomson seems to allude, the death toll of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico was not just the six to 18 that Trump claimed died directly in the storm, but upward of 3,000, resulting from mostly preventable causes like lack of drinking water and insulin. Thomson rightly calls the situation in Puerto Rico well before the storm “a disaster waiting to be identified.” Disasters, scholars like Knowles have shown us, are not freak one-off events, but drawn-out processes as complex as the societies they strike. And in the Anthropocene and what Andreas Malm calls a dawning era of “chronic emergency,” we can no longer consider events like storms or pandemics “natural disasters” at all. Disasters are social; they are not other, and they are certainly not just a Trump blimp looming over our helpless forms; they are us.

Despite their occasional convergences, critical disaster studies, centering the question of power — disaster for whom? — raises problems for Thomson’s neat thesis that “we want our fears of physical ruin rendered as something so beautiful we feel no pain.” After all, the way we derive pleasure from disaster when viewing or imagining it from the safety of our living room sofas has been troubled ever since Kant reflected on our “awesome shudder” at nature’s “sublime” centuries ago. Scholars have long probed the limits of representation when it comes to “limit events” like the Holocaust, and Thomson is right to acknowledge that some disasters evade beautification, striking us “like Vermeer trying to paint Auschwitz.” But Thomson nevertheless accepts and naturalizes the tendency to aestheticize disasters in order to live with them: “We know this glee is close to madness, but that is how we play with the prospect of our demise.”

Here he comes into contradiction with what I would call the tradition of critical catastrophism exemplified by the German Jewish theorist Theodor Adorno. Whereas Adorno charged right-wing prophets of decline like Oswald Spengler with making “common cause with catastrophe,” Adorno held that after the barbarity of Auschwitz, Hiroshima, and Vietnam, along with the threat of total nuclear annihilation in the Cold War, the true meaning of progressive politics had become “simply the prevention and avoidance of total catastrophe.”

Such an anti-catastrophist stance is adopted by the Austrian literary scholar Eva Horn in her very different account of Western culture’s long obsession with disaster. Her book The Future as Catastrophe: Imagining Disaster in the Modern Age (Columbia University Press, 2018) shows that the modern tendency to aestheticize apocalypse goes back at least to the Romantic literary milieu that produced Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826) but has since undergone a number of transformations. Whereas science fiction films in the Cold War era demonstrated species-wide collective action warding off alien invaders, disaster films in our neoliberal era (San Andreas, I Am Legend) portray a retreat into the rugged individualism of the family, a survival of “bare life” against all odds after the end of social cooperation.

Horn also observes that we have become used to living in what Ulrich Beck called a “risk society,” plagued by persistent but diffuse, latent, and often imperceptible threats like nuclear annihilation or climate collapse. She calls this unbearable situation of living in uncertainty and suspense the problem of “catastrophe without event.” The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, makes for a bad story because, as Thomson notes, “[i]t has no willful design, no dramatic character,” for “the virus is as impersonal and undirected as a tide coming in.” As the historian of medicine Charles Rosenberg famously argued, it’s much easier for us to recognize and respond to pandemics like cholera with “melodramatic” symptoms and “a dramaturgic form” than slow-moving killers like HIV/AIDS or the grab-bag of grave symptoms (or lack thereof) that marks COVID-19 infection.

For Horn, disaster films and fiction, punctuated by discrete events like the push of a red button, the strike of a meteor, or the escape of a zombie monkey from a lab, give our psyches the concrete and dramatic turning points they yearn for. This explains the palpable satisfaction Thomson observes watching San Andreas in the theater when the fault is set off and the audience’s anticipation is relieved: “There is an erotic charge in delivered disaster — it’s the deliciousness.” Giving disasters direct causes — as against the nearly unnarratable “conceptual event” of climate catastrophe — restores our sense of agency and displaces our anxieties about diffuse threats onto actors on the screen “over there.”

But therein lies a danger: projecting disaster elsewhere can lead to catharsis but also quiescence. Susan Sontag identified this problem in her 1965 essay, “The Imagination of Disaster,” which argues that we live torn between two continual threats: “[U]nremitting banality and inconceivable terror.” One thing fantasy does, she wrote, is “lift us out of the unbearably humdrum and to distract us from terrors, real or anticipated — by an escape into exotic, dangerous situations which have last-minute happy endings.” Horn also notes the dangers of aesthetic escapism, but ultimately sees them outweighed by the positive, preventative potential for rehearsing disasters through imaginative and artistic means.

Thomson, however, seems to simply accept the way “anxiety can be aestheticized” by the pop culture industry through blockbuster disaster films and concludes that “[o]ur one provision against catastrophe and the cataclysm is to reassess it as a genre.” These may be the limits of one critic, but they are not the limits of criticism. Walter Benjamin once wrote that “[m]ankind’s self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.” But Benjamin saw this not as a given, but as a damning indictment of late capitalist society and its ideology. Giving up on art’s capacity for critique, Thomson offers us a complacent alternative, “a way of reconciling horror with attraction — disaster mon amour.”

Thomson sees this as a way of learning to live with disaster, once “our epic,” now simply “our context.” His often tedious pandemic diary sections reflect well enough the unremitting banality of daily life under lockdown, but quotidian disaster goes well beyond the sphere of “the comfortable bourgeois way of things […] disasters no more perilous than the breakup of a marriage, the early death of a parent, or the difficulty of finding good Sage Derby cheese.” Other critics have put theoretical terms to this formation: “banality of catastrophe” (Anson Rabinbach), “slow violence” (Rob Nixon), “crisis ordinariness” (Lauren Berlant). These notions capture how structural violence and ongoing disaster are never entirely absent, even when they elude our perception. Others today even speak of the chronic anxiety of “climate grief.” Surely this new social condition also calls for new modes of filmic representation and perception.

Thomson considers the “sweet marvel” of stunning special effects to be the backbone of the disaster film genre, which enabled the cinematic shift from depicting reality to creating “a simulacrum of things no one had ever seen.” But the ecstasy special effects can generate need not lead us into quiescent rapture at our own sublime destruction. Disaster can be brought back into the service of social critique. Adam McKay has valiantly attempted to do this for climate change in his polarizing and on-the-nose Don’t Look Up (2021), while Neill Blomkamp has crafted fantastic parables of structural racism in District 9 (2009) and health inequality in Elysium (2013). However, the displacement of reality by fantasy cuts both ways. In a way, Thomson updates Sontag’s reflections on our love of disaster for an era in which screens mediate much of our “altered or numbed” relationship to reality. The “constant crosscutting” between media through which we now experience the present no longer holds the emancipatory promise it once held for Walter Benjamin, who saw in the shock-filled montage of films like Battleship Potemkin the seeds of revolutionary awakening. Today, our attention has been sold out. Pop-up ads for beer and $1 boneless wings blared over the CNN headline, “RUSSIA INVADES UKRAINE.” But then again, as Thomson writes in a representative bromide, “[M]aybe everyone behaves like an idiot in a disaster?” — or at least when monetizing it.

Our cultural memory of disasters is, to say the least, uneven. Thomson’s beloved Hiroshima mon amour meditates on the paradoxical relation between memory and forgetting — remembering to forget. At the same time, he reflects, “We cannot give up on the imaginative effort, the sympathy, that wonders what it’s like to be disastered.” Forgetting can’t have the last word so long as “[d]isaster cries out for witness.” While Thomson pities the tragedy of disasters forgotten or ignored, he lacks a framework for grasping how systematic those exclusions can be. As the late critic Lauren Berlant noted in these pages: “[P]olitics is constituted by a disagreement about whose representation of the event will secure protocols and resources for valuing some claims and grievances over others.” Dara Z. Strolovitch similarly distinguishes between hardship that is dismissed as “non-crisis” versus that deemed “crisis-worthy” and deserving of state intervention; her forthcoming book provocatively defines crisis as “when bad things happen to privileged people.” Whose suffering is considered normal, and whose is a disaster?

More clearly than any other thinker today, Cornel West brings out the humor, beauty, and virtue that can arise from ongoing oppression, injustice, and exploitation — reminding us that in ancient Greece catastrophe referred to the turning point in a tragic drama, an occasion for catharsis, collective release. West has emphasized, “There’s never been a ‘Negro Problem’ in America; it’s been a catastrophe visited on black people.” Faced with catastrophe, West’s progressive spiritual outlook sees occasions for song, socialism, and “soulcraft,” while Thomson’s liberal quietism musters only “discovered regret over racism.” It is telling that when Thomson began writing about disaster, he had in mind chiefly the climate crisis, then pivoted to the pandemic, then, like many of us, pivoted again to racial injustice after the police murder of George Floyd and the summer of uprisings that followed. But, instead of endlessly turning our distracted minds from one disaster to the next, what if we were able to hold our attention on several at once, and reflect on their considerable overlaps? Might disaster films help us do that?

“Time and again,” Thomson writes, “disaster asks more testing questions about the structure of our society.” We should use such moments of disaster — real and imagined — as occasions to hear those questions, to internalize them, to be moved by them. Thomson ruefully accepts that “we have digested disaster; it is our music and our rhythm, despite the damage done in its name.” But against the impulse to wash down disasters with a mouthful of popcorn and a gulp of soda, criticism, at its best, spits it back up and shows us its ugly, undigested kernels.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jonathon Catlin ([email protected]) is a PhD candidate in the Department of History and the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities at Princeton University, where he is writing a dissertation on the concept of catastrophe in 20th-century European thought. His popular writings have appeared in The Point, The Spectator, Post45 Contemporaries, Public Seminar, and The Journal of the History of Ideas Blog, where he is a contributing editor. He lives between Berlin and Brooklyn.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Need to Talk: On Marguerite Duras’s “The Darkroom”

“The Darkroom” is a critique of aesthetics and politics, and a meditation on the end of the world.

A Very Acute Watcher: A Conversation with David Thomson

Jonathan Kirshner interviews David Thomson on his book “A Light in the Dark: A History of Movie Directors.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!