What Fourth Wall?

On "Sleep No More," Punchdrunk theater company's reimagining of "Macbeth"

By Tara Isabella BurtonJuly 31, 2013

Image credit: Gal Stark Arad-Kabiri

WHEN RITA — the brash Liverpudlian hairdresser from Willy Russell’s 1980 play Educating Rita — recounts her first visit to the theater, she remembers her desire to shout out a warning to Macbeth at some crucial point on his road to doom. “You wouldn’t have been able to stop him, would you?” responds her tutor, trying to explicate the difference between chance misfortune and tragic inevitability. Rita remains characteristically pragmatic. “They would have thrown me out of the theater,” she answers.

What a time she would have had at Sleep No More, the interactive, site-specific reimagining of Macbeth, now in its third year at New York’s McKittrick Hotel — three adjoining Chelsea warehouses transformed into six floors of intimate bedrooms and grand ballrooms, labyrinthine forests, stale graveyards, and unsettling empty padded cells. In these 90-some rooms, audience members are free to colonize the space — to open drawers, rifle through papers, and, most enticingly, interact with the characters themselves.

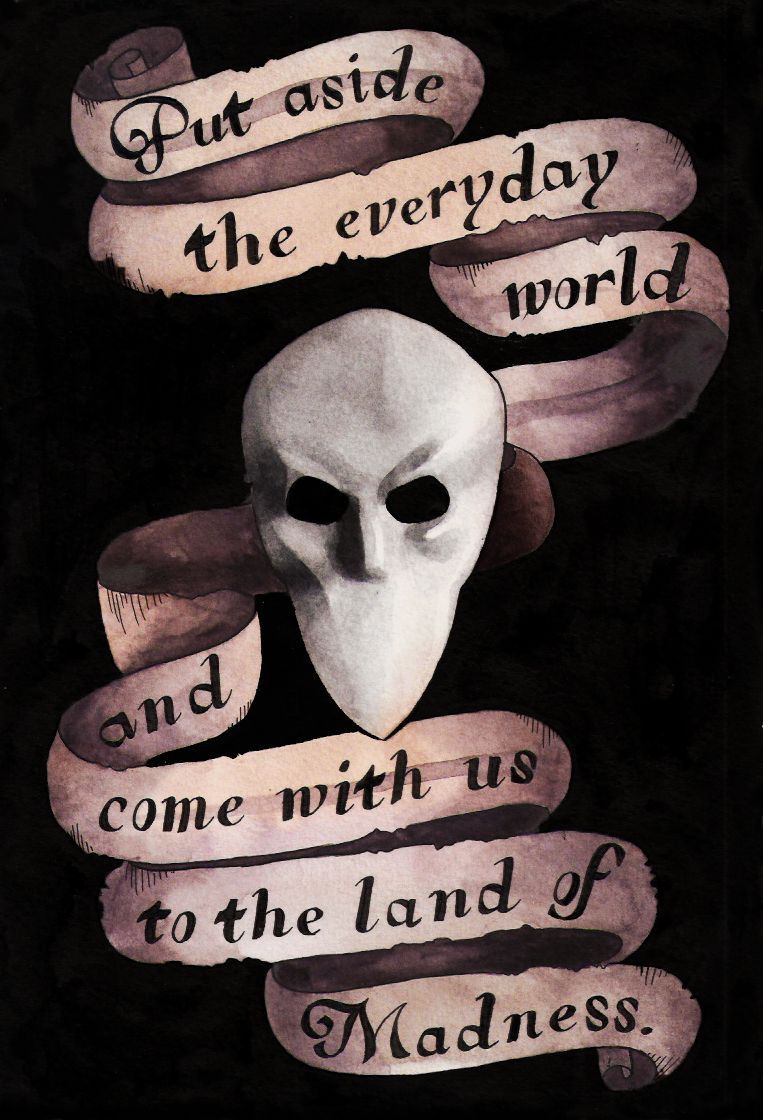

Sleep No More is produced by Punchdrunk, a British theater collective that aims not only to break down fixed boundaries between audience member and performer, but to make each viewer part of the story. Outfitted in full-face white masks, the audience is sent forth looking spectral, instructed only to keep on the masks and to stay silent no matter what. Depending on which way you go, you might encounter Lady Macbeth, raving through the shadowy streets of Glamis — here conceptualized as a sleepy 1940s-style hamlet, complete with a fully outfitted sweet shop. Our Lady looks bedraggled in sequins, murmuring incoherently (listen closely and you might make out the words “damned spot”). If you catch her eye and prove yourself worthy of her trust, you might find yourself embracing her. Or you might watch that same scene from the window of a Glamis funeral parlor, barring the doors and praying for deliverance from this reign of witchcraft with the town’s local tailor. You might watch King Duncan and his retinue dance to Glenn Miller in the grand ballroom, and, if you’re close enough and spry, you could catch Lady Macduff as she swoons after drinking from a poisoned glass.

For Sleep No More’s most devoted fans, few experiences prove as powerful as that initial breaking of the fourth wall: the first one-on-one encounter with a fictional character. Meg Brophy, box-office manager for Michigan's Barn Theater, and a long time Sleep No More fan, recalls the dreamlike intensity she experienced the moment Lady Macbeth's nurse turned to her to take her hand.

Like the rest of the audience members attending Sleep No More, Meg enters the McKittrick through the Manderley, a debonair (and fully operational) 1930s-style cocktail bar, where actors in period garb ply her with compliments before taking her, along with 14 other audience members, into a private room. One of the barfly flappers hands out the white masks — the anonymity, Meg is told, is “for your protection” — before ushering them into an elevator under the command of the McKittrick bellhop, James.

The bright, blues-inflected conviviality of the Manderley gives way to eerie, echoing silence. When the elevator opens, Meg is the first one out — turning just in time to see the doors close with her fellow theatergoers still inside. She is alone in the shadows of the King James Sanatorium, a chillingly antiseptic asylum for the insane and bewitched, which will ultimately house Lady Macbeth herself in her darkest hour. Bathtubs — some blood-stained — are lined up in rows; in another room, across the hall, empty hospital beds await their patients. Offices are outfitted with medical textbooks cut into strange shapes, locks of patients’ hair, dubious-looking vials. In one padded cell, feathers pressed into the linings of the walls mirror the floor patterning of the king's ballroom five stories below, evoking the avian motif so prevalent in the text of Macbeth, where auguries in the sky foretell the coming chaos below.

But Meg has little time to take in her surroundings. Within seconds, a petite nurse takes hold of her hand and brings her into a private ward, which she duly locks behind them. She gestures for Meg to climb into a bed, which she does. The nurse sits down next to her and gently, almost tenderly, removes her mask, brushing back some of her hair. Then she kisses Meg on the cheek before turning her face toward wall, on which is written an ominous prophecy foretelling Duncan's murder several stories below. Wordlessly, the nurse conveys her fear that — even in this secluded space — they are being watched. She leans across Meg’s chest, letting Meg support her weight, as she tucks her into bed as she would a child, holding her still. Suddenly the nurse is overcome by a convulsive, witchcraft-induced, coughing fit that culminates in her spitting up nails across Meg's chest. “Infected minds to their deaf pillows discharge their secrets,” the nurse whispers, before at last allowing Meg to get up, hastily returning her mask and pushing her out the door. “Tell no one,” she says.

Such an encounter — which violates not only the rules of traditional theater but indeed the personal-space taboos of normal social interaction — might terrify some or seem, at least, uncomfortably intrusive. But for Meg, the encounter proves intoxicatingly intimate, powerfully addictive: a moment — despite its performative context — of genuine emotion.

“Leslie [Kraus, one of the actors who regularly plays the character Nurse Shaw] was so calm and caring,” Meg later tells me, “She has this way of staring into your soul that really moved me.” When Nurse Shaw tucked her into bed, Meg says she felt simultaneously vulnerable and protective of this diminutive redhead and their sudden intimacy. Nurse Shaw’s coughing fit, which escalated so that it seemed the woman could hardly breathe, paralyzed Meg. “I wanted to get up and help her,” she recalls, but she was no more able to interfere than Russell's Rita. “There was nothing I could do but sit and watch her suffer.” Meg says that her empathy for this character was more intense than she had ever experienced in a traditional theater setting and that she believed herself to be more than a spectator. She had become part of the drama.

While Meg endured Nurse Shaw's coughing fit, other audience members were being similarly deployed. Another viewer is ushered by a sultry, red-dressed Hecate into her burlesque-style boudoir, where this goddess of witchcraft removes her guest’s mask and gives her a vial of harvested tears to drink while telling a story about a little boy lost in a wood. Elsewhere, one of Hecate’s sprites, a slim supernatural creature known as Boy Witch, seats a few people and serenades them with a genderfluid lip-sync of Peggy Lee’s “Is that All There Is,” afterwards selecting one of them to push into a telephone booth in the grandly decaying McKittrick hotel lobby for a brief erotic kiss or caress.

Meanwhile, on the third floor, the virtuous Lady Macduff, heavily pregnant and desperate to free her wayward husband from the thrall of Hecate's witches, seeks help from an audience member. Bringing her confidante into a locked chapel off the Macduff family living room, she takes some salt from a dish — for protection, we learn — and rubs it behind her choice's ear before clasping her hand in murmured prayer.

¤

The show’s self-proclaimed “super-fans” — regular visitors to the McKittrick, many of whom congregate online under Macbeth-inspired monikers like scorchedthesnake and washthisblood — are legendary in their devotion: posting theories about hidden relationships among the show's numerous characters; showing off home-made regalia, like a coin stamped with the McKittrick insignia (with which to tip the bellhop); and fevered speculation about Punchdrunk’s newest show, the Woyzeck-inspired Drowned Man, recently opened in London. Undeterred by Sleep No More’s price tag ($75-$95, depending on night and time), the show’s most prolific devotees return a dozen times or more; one blogger I met in the Manderley bar was on his 53rd visit.

What is it, then, about Sleep No More — and indeed, about Punchdrunk's immersive experience more generally — that inspires such fervent devotion? I can hardly claim to consider the show without bias; I’ve written about my own “first time” for The New Statesman, and I found my three subsequent visits equally, narcotically, intense.

Obsessive theater fans are nothing new: when Sarah Bernhardt toured America in 1880, she was besieged by mobs and journalists alike. Phantom of the Opera “phans” and Rent-heads have been congregating in pockets of the internet for decades. Yet, in the absence of a clearly defined boundary between audience member and performer, regulars at the McKittrick experience what most book, film, or show fans can only dream of: they are not only observers, appreciating the work of the artists they love, but also participants, inhabitants — at least temporarily — of the world they have come to love.

“That certainly was my dream as a kid — to jump in and interact with Princess Leia or Indiana Jones,” recalls Jason Pates, a recent convert to the show. Like most of the other fans I've interviewed, he dates his love of Sleep No More to his first personal interaction with a performer — an erotic ballroom dance with the Bald Witch (Hope Davis) during his first visit to the McKittrick. A few hours later he booked a ticket for the following night. “It's like a switch went off and the power of this art form became clear […] your first personal interaction is the catalyst. It feels like the story is choosing you to be a part of it.”

It’s one thing to imagine a romantic tryst with Indiana Jones or Princess Leia. But it's quite another to be kissed on the neck in a telephone booth, as I was on more than one occasion by the sexually rapacious Boy Witch (Austin Goodwin). Indeed, the erotic potential of such transgression seems to be a large part of the show's appeal; as one of the show’s New York artistic associates puts it in an interview with Culturebot’s Agnes Silvestre, “A good one-on-one should perhaps make you fall in love.”

Punchdrunk’s founder Felix Barrett, in a recent Financial Times interview, notes that audiences “get out what [they] put in. It becomes something that’s yours and yours alone. And it’s real: you’re not interacting with a pixel.”

Yet how real is real? For Sleep No More to succeed as a piece of theater, it must convince its audience — at least for the three hours of the show — that their interactions with Lady Macduff or Malcolm are true relationships, emotionally fraught on both sides. And yet to do so is to fuse fiction and reality in a manner that may feel uncomfortable, even dangerous, and on both sides (stalking on the part of besotted fans is not unheard of).

A Star Wars fan must to come to terms with the fact that Princess Leia will never requite his affections, indeed that she does not in fact exist. It is much more complicated to stare, as I did, across the Manderley floor at an out-of-costume Elizabeth Romanski, minutes after sharing a particularly intense scene with her in Hecate's boudoir, and realize that she has no idea who I am.

Had I, I wondered, simply fallen prey to emotional slight-of-hand, rationalizing my erotic reaction to being fondled by a beautiful performer in a private room? Was I — were all of Sleep No More’s dedicated fans — engaging in a form of psychological prostitution, paying almost $100 for a chance to kiss a pansexual witch in a telephone booth? Certainly, Agnes Silvestre, in her Culturebot article “Punchdrunk and the Politics of Spectatorship,” takes a somewhat cynical view of Sleep No More’s approach. For her, “the relationship of consumer to product colours every aspect of the piece, and creates the architecture for the interaction between audience and performer.”

Punchdrunk is preceeded by the pioneers of modern interactive theatre — Brazilian activist/director Augusto Boal, for example, developed his Theater of the Oppressed in the 1950s, when a “spec-actor” in the audience could stop the drama and take the place of an actor. A decade later came The Performance Group's Dionysus in '69 — which interspersed the audience among the actors in an orgiastic, participatory retelling of an ancient Greek tragedy. But unlike in Boal's work, or in Dionysus in '69 (where a group of audience members once kidnapped an actor to spare him from his tragic fate), Sleep No More viewers are not given the agency to change the drama. They are prevented from actively interfering with the performance's outcome.

How, therefore, are we to read the breakdown between spectator and actor in Sleep No More? Is it — as Silvestre suggests — a largely gratuitous device for audience titillation? Or does it pose the possibility, for the careful viewer, of a mode of catharsis different from what is offered by more traditional theater?

Anxious to unpack my own powerful reaction to Sleep No More, I booked four performances in a row, comprising 12 hours in the McKittrick over the course of four days. On the first night, against my better instincts, a friend and I indulged ourselves with a pre-show “secret dinner party” at the McKittrick's new sixth-floor dining space. Soon into the meal I knew I had made a mistake. The food — though delicious — was in short supply, hardly meriting the $65 price tag. Actors, playing assorted denizens of the McKittrick's glamorous, faux-30s world, plied me with champagne and called me “darling,” an experience, like Silvestre’s, more transactional than transcendent.

As one of our hostesses led us to the door to the performance area and handed us our masks, I began to dread my return to the McKittrick, fearing that a critical eye would reveal a theatrical experience no less manufactured. But once I entered the space, I found myself dashing down the stairwell in pursuit of the Thane of Cawdor and his wife, experiencing the same adrenaline rush that had characterized my first visit to the world of Punchdrunk. I watched Lady Macbeth and her husband grapple on a series of trunks and cabinets in their bedroom. I saw Macduff, his wife, and the witches dance in a grand ballroom, as Macbeth himself watched from the mezzanine above.

And, once again, I found Sleep No More’s most powerful moments were not its most spectacular — the erotically charged acrobatics, the sweeping ballroom scenes and stunningly intricate sets — but rather its most intimate. No less compelling than the story of Macbeth himself is the story of Sleep No More's porter, not the bawdy ribald of Shakespeare's original but rather a timid clerk at the McKittrick Hotel whose interactions with many of the show's major characters spur the plot toward its inexorably and grisly end. On this occasion, I found him alone in the hotel lobby, trying on the dinner jacket of the Boy Witch, the object of his ill-fated and unrequited affections. We shared a glance, reflected in a hallway mirror, and I decided that he was the character I would follow for the rest of the night. My attention was focused wholly on his story — the prophecy he inadvertently delivers to Banquo, his guilt in his complicity, unwitting or otherwise, in Macbeth's saga, his desperate, hopeless love for the Boy Witch.

One of the most powerful scenes in Sleep No More is the “telephone booth” dance, an intensely acrobatic push-pull pas de deux between the Boy Witch and the besotted Porter that culminates in the Porter’s humiliatingly rejection when Boy Witch throws him to the floor. On this particular occasion, I watched the audience members tense up, gasp, sigh — with sympathy, with longing — as the dance played out with particular violence, before the Boy Witch strode away, forcing a choice for the viewer: me or him. I stayed, and the Porter rewarded my loyalty. He took my hand. He led me along the corridor and into a private room. He locked the door. Slowly, painstakingly, he took off my mask.

Of all Sleep No More's devices for unsettling its audience members, the removal of the mask is most transgressive, most intimate. This removal violates not only the rules of traditional theater (seats, curtains, proscenium arch) but, more crucially, the rules as stated at the start of each performance: masks are to be worn at all times. They are, we are instructed, our guarantors of anonymity; they are what delineates performer and audience member; they are given to us, we are told, “for your own safety,” an enigmatic warning that serves to heighten the McKittrick's atmospheric intensity.

Alone with the Porter (Will Seefried), such defensive boundaries had dissolved. To be face to face with another human being in a drama that he was more or less controlling felt strangely, overpoweringly, intimate. He cupped the sides of my face and waited for me to build up courage to meet his gaze. He took down a box from a shelf and began to finger its contents — a wig, lipstick — before trying both on in front of a hand mirror, expertly angled to face me. He considered himself — at once beautiful and grotesque, a burlesque parody of femininity — before breaking down in tears. He turned to me once more, pushing me up against the door as he wept in my arms. He kissed me on the cheek and I could feel his tears. “Thank you,” he whispered.

It would be possible, of course, to reduce the power of this encounter to its sensual components — the claustrophobic nature of the space, the feeling of being chosen — but, beyond that lies the more interesting question: If this were real, would you be doing this right now? Do you believe that it is real, now? Even the most metaphysical traditional theater production, even the works of Beckett and Pirandello, have never challenged my understanding of the tenuous balance between reality and fiction as powerfully as this.

The social rules that govern our experience of traditional theater prevent us from “shouting out,” as Russell’s Rita longed to, to warn Macbeth of the doom to come. We forget, of course, we can shout out, interrupt, insinuate ourselves into the proceedings; that the performers are as vulnerable as we are ourselves. Here, with no stewards or ushers to throw me out and no other patrons to shush me, I found myself painfully conscious of the agency the Porter had surrendered to me. It would have been easy, given the strangeness of the situation, to laugh, to giggle, to grimace, to diminish character and actor alike with a single smirk or raised eyebrow. Instead, I found, I felt compelled to listen to him, to dry his tears, to comfort him in his grief, to be present both for the Porter and for the actor, really, at that point, unable to separate the two. In the moment, I believed in his tears. I did not stop myself. I kissed him back, on the other cheek, and he pushed my mask back on, pushed me back out to where other audience members stood masked and waiting for him to reappear.

Immediately my fear returned — had I crossed some invisible boundary, transgressed in reality, rather than the controlled, manufactured transgressions the one-on-one encounter purports to represent? My reaction to the Porter's scene, it becomes apparent, is hardly unique. Rachael Stevens, another Tumblr super-fan, blogging — along with her boyfriend Robert — as thepaisleysweets, describes the feeling of being “honored” by her encounter: “The Porter was sharing something so clearly painful and intimate. He was trusting me with the knowledge of what has happened to him and how he has suffered for his choices.”

It is perhaps unsurprising that, among Sleep No More fans, the Porter's 1:1 is among the most sought after. Indeed, many of the show's most coveted interactions among super-fans — dressing a distraught Boy Witch, catching a fainting Lady Macduff at the ball — seem to be those characterized by the highest degree of performer vulnerability.

Yet the vulnerability is not one-sided. In inviting audience members to comfort them, to lock eyes and engage in these emotional dialectics, characters like Lady Macduff and the Porter allow viewers to bring to the surface their own insecurities, their own fears; more than one Sleep No More fan has admitted to weeping in the middle of an encounter.

Removed from the complexities of normal social interaction — pre-existing relationships, attendant consequences — we are free to experience the intimacy inherent in simple human presence far more readily than we would in the world outside the McKittrick, where — like in Rita's Liverpool theater — such intimacy comes constrained by societal norms. The artificiality inherent in our circumstances — after all, when else will we find ourselves chasing down regicides? — only heightens the intensity of the interaction, freeing us to engage in its emotional reality.

Yet, I cannot help wondering, are the performers themselves equally invested in the reality of the moment? Kelly Bartnik, who has played the Bald Witch (among several other roles) since Sleep No More’s first Boston run, and who was instrumental in developing the character further. “It isn't really an option to be removed,” she says, “the audience is close enough to you to read your sincerity. If you're not willing to be exposed and open, then you lose their interest. This is one the most fulfilling things about performing this way. Each connection, and there are many, is valuable and honest.”

Ultimately, this connection proves less a seduction than a kind of self-offering. As I helped a tearful Boy Witch clothe himself after a rare post-orgy breakdown, as I comforted Hecate in her boudoir as she mourned the loss of a mysterious ring, I found the encounter less erotic than emotional. I rejected Silvestre’s suggestion that I was in a world where “desire is created, and then capitalized upon.” Rather, I was potently conscious of the power I did possess: of the choices I was making, at every moment, to keep the theatrical magic alive. Performers trusted me; I, in turn, actively worked to deserve that trust. Their faith was a gift to me; my receptivity became, in turn, a gift to them.

This, then, is the genius of the McKittrick. On the one hand, the world of the Macbeths is removed enough from the Chelsea warehouses that surround it to allow for catharsis, for identification with characters whose passions and desires are powerful enough to allow us to forget our own. Yet such catharsis, on its own, is hardly unique to Sleep No More. Rather, what makes Sleep No More's approach to interactive theater so distinct is the manner in which these cathartic encounters allow, even encourage us to foster a genuine human connection in the midst of a surreal, fictional world.

In Marina Abramovic’s 2010 performance piece The Artist is Present, the artist sat immobile and silent for 736 hours (six days a week, seven hours a day) while spectators took turns sitting opposite. For some, it was a quasi-religious occasion; tears were frequent shed on both sides of the table at a theater event at once public and highly intimate. Like The Artist is Present, Sleep No More provides its visitors with a liminal safe space, in which the traditional relationship between performer and audience member, between storyteller and listener, takes on a new and dynamic form, one defined by its mutuality

As I wandered through the halls of the McKittrick over the course of the next three nights — through the Macbeth’s ballroom, through graveyards, crypts, forests and boudoirs — the story of Sleep No More came to take on ever more complex dimensions. Smells, music cues, letters hidden in drawers in Malcolm’s office or Duncan’s writing-desk, all evoked in me not only the Macbeth’s history, but also histories of my own: moments of nostalgia, vulnerability, of fear or love pragmatically forgotten, all re-awakened by the intensity of Sleep No More. As I wandered alone in the Macduffs' bedroom, or in Hecate’s dilapidated speakeasy, the agency I was given as an audience member allowed me to piece together from the show’s fragmentary, nonlinear narrative a story that was entirely my own: drawn at once from the world I saw in front of me and from the interior landscape the McKittrick gave me the freedom to evoke.

I was, apparently, far from the only audience member to feel this way. One night, as I made my way to the fifth-floor asylum, I caught the eye of another masked audience member, who stopped short in his tracks. He stared at me for 10 seconds, his gaze increasingly desperate, before leaving the audience group following Nurse Shaw to follow me instead, catching my eyes again and again, as if to say, Don't you recognize me?

The McKittrick, fans say, likes to play tricks upon its residents. I became convinced — tentatively at first and then quite definitely — that behind the mask was an old lover, someone I had not seen in years. Stymied by the enforced silence, we did not speak but instead walked together — following one another into room after abandoned room, through the brambles of a forest, into a hidden office, a padded cell, creating a story of our own while the Macbeths danced their last duet four floors below. We lost each other by the fourth-floor candy shop, and were only reunited after the show's end, back at the Manderley. Once we were unmasked, the truth became clear: we had never met before. Overcome by the romance, the melancholy of the McKittrick, we had each convinced ourselves that we knew the other. It wasn't true, of course — but in the world of the McKittrick such coincidences feel not only possible, but inevitable. Our relationship was a fictive one, but our encounters, no less than the Porter's one-to-one, were infused with emotional truth. We each became — for the space of an hour — the person the other needed us to be.

In her Notebooks, the French philosopher, theologian, and mystic Simone Weil writes passionately about the concept of “decreation,” the idea that creation — in its most powerful sense — demands self-denial. A truly loving God, for Weil, does not merely create but also abdicates: allowing human beings space to experience their own agency, their own freedom, to bring their own selves and experiences, to the table of existence: “The act of Creation is not an act of power,” she writes, “It is an abdication.” Sleep No More celebrates that same spirit of self-offering. These twin “abdications” — the vulnerability embraced by the performers and the active, witnessing presence in which we as audience members are invited to participate — are an important development, a new approach in the relationship between performer and spectator: one based not in relationships of power, but, to borrow Weil's terminology, acts of love.

¤

LARB Contributor

Tara Isabella Burton is working on a doctorate in literature and theology as a Clarendon Scholar at Trinity College, Oxford. Her work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in National Geographic Traveler, The Paris Review Daily, The Atlantic, Electric Literature, and more.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Ordinary Magic: A.L. Kennedy’s Transatlantic Tricksters

Kennedy’s latest novel, a quasi-love story about fake mediums, is carried and hindered by the acclaimed writer’s mordant humor and metafictional play.

What’s Left to Say? Four Fitzgerald Scholars on Baz Luhrmann’s Gatsby

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!