“What Else Would Heaven Be”: On Shane McCrae’s “Sometimes I Never Suffered”

Will Brewbaker considers “Sometimes I Never Suffered” by Shane McCrae.

By Will BrewbakerOctober 13, 2020

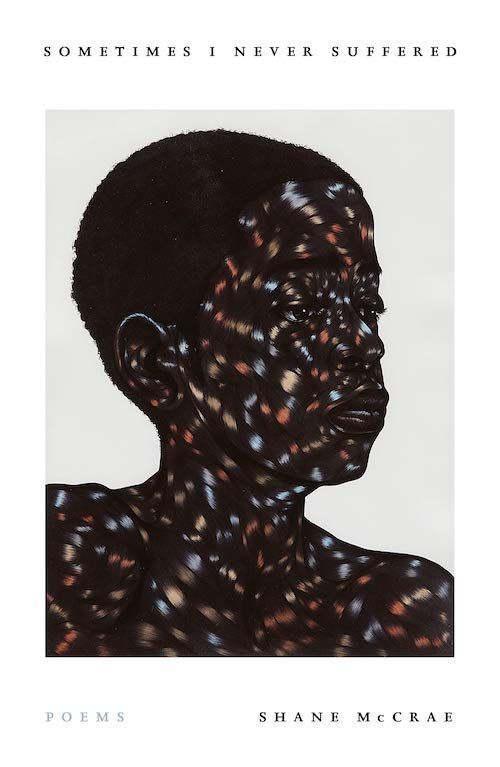

Sometimes I Never Suffered by Shane McCrae. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 112 pages.

DANTE ALIGHIERI’S NAME appears only once within his Divine Comedy. Near the end of Purgatorio, the second of the epic poem’s three parts, the pilgrim hears that single word — “Dante” — spoken by a “a lady […] girt with olive over a white veil.” The woman is, of course, Beatrice — Dante’s childhood love who died at a young age and who serves as the epic’s divine magnet, pulling Dante toward the light of God’s purifying love.

Beatrice’s naming of Dante is notable not only for the way it bridges the gap between the Dante who writes the poem and the Dante who lives it, but also for its bold particularity, its remarkable this-worldliness. Having passed through hell’s torments and purgatory’s refining fires, Dante finds himself standing, in this moment of naming, in the earthly paradise — ready, at last, to ascend to heaven. As the poem prepares to launch into the Paradiso’s celestial unreality, the name “Dante” tethers the poem to this side of Paradiso — to the world where each of us lives.

This act of holding together both heaven and earth pervades Shane McCrae’s Sometimes I Never Suffered, the prolific poet’s latest collection. Racial injustice, economic inequality, simple human cruelty — McCrae addresses all of these subjects, these facts of the world, head-on — while, like Dante, transposing the literal into the otherworldly.

As the book’s preface notes, Sometimes I Never Suffered stands as the final section of McCrae’s Dantean poem entitled “A Fire in Every World” — which began with a long section entitled “Purgatory/A Son and a Father of Sons” from In the Language of My Captor (2017) and was continued by “The Hell Poem” (The Gilded Auction Block [2019]).

Considering these previous sections — purgatory and hell, in that order — it comes as no great surprise that Sometimes I Never Suffered takes place — in large part — within a (mostly) Christian heaven. Whether following the exploits of the “hastily assembled angel” — who finds himself pushed by his jealous angelic colleagues down to earth early on the third day of Creation — or presenting the historically factual Jim Limber (who reprises his role from McCrae’s “Purgatory” poem) as he details his experiences of racism in heaven, Sometimes I Never Suffered uses its celestial motif not to escape this world but rather to bring it into sharper focus.

“I’ve been a long time dead without my life,” Jim Limber declares in the collection’s opening line. He goes on:

I think now more than half

Of life is death but I can’t die

Enough for all the life I see

Like the presence of Dante’s name in the afterlife, these lines question what to call the life that arrives “after” life — especially, as in Limber’s case, if that life is marked by the same pain and suffering as the one that preceded it.

With this ambiguous missive from heaven in place, Limber — the mixed-race, adopted son of Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina — disappears, ceding the narrative stage to a new character entirely: “the hastily assembled angel.”

The 12-poem suite that follows — which stands as a remarkable achievement of both narrative and lyrical ingenuity — reads like a spin-off series from the first chapter of Genesis. According to McCrae, the angels learn of God’s plan to create humans and — in a bout of fear and pride that recalls both the Dantean and Miltonic Lucifer’s rebellion — decide to “[b]uild their own angel” in angelic protest against the divine. But whereas Lucifer falls “like lightning,” this angel falls in a disorganized panic:

and as Gabriel

Asked God if this new angel could be sent

Instead to Earth fresh eyes for a fresh World

The other angels shoved the thrown- together angel

from the clouds and Heaven

The poems that come after this heavenly expulsion trace an elliptical path across (a largely biblical) human history: the angel watches curiously as the first humans fashion gods for themselves; he survives the flooding of the earth; he sees a slave murdered by his Egyptian masters at a pyramid’s construction site and, in the next poem, wanders alongside the Israelites in their desert exodus.

In the wrong hands, this sweeping flyover of human history might be too big to chew. But McCrae has no designs on totality: these moments are lyrical flashes, not summarizing instances — as when he offers an explanation for the angel’s “patchwork wings,” which are made up of “blood and emptiness / And sun.” In that poem’s final lines, McCrae envisions Azrael (the angel of death in some Islamic and Jewish traditions) noticing that the hastily assembled angel

had

No wings and paused and thought then pulled him back

And so the angels stitched together what was

Near blood emptiness sun since what was near

Was Heaven and what else would Heaven be

Taken on their own, each of these composite parts — blood’s vitality, emptiness’s peace, the sun’s life-giving warmth — might fit into a traditionally received notion of an angel. But together they offer an image almost uncanny in its execution. That such a dire mixture might come from a world of perfection leaves us wondering into what kind of heaven McCrae, Beatrice-like, has led us.

At the end of the hastily assembled angel’s opening section, he wonders how his life might have been different had he been allowed “to meet God”:

for he has been uncertain

As people are uncertain he has nev-

er been as certain as dogs are who sniff

The wind that moves the curtain and see behind the curtain

Moments like this one — which feel more human the further from earthly reality they get — call to mind the critic Erich Auerbach’s observation about Dante’s Comedy: “The human world in all its breadth and depth is gathered into the structure of the hereafter and there it stands: complete, unfalsified, yet encompassed in an eternal order.”

These descriptors — “complete, unfalsified” — apply doubly to the extended middle sequence of Sometimes I Never Suffered, which reads like dispatches from Jim Limber’s time in a heaven that more closely resembles earth. As with the story of the hastily assembled angel, Jim Limber’s heaven finds “blood and emptiness / And sun” — but it also finds the harsh, “unfalsifiable” realities of racism that marked so much of Jim Limber’s historical life.

One of the most paradoxical figures in American history — and perhaps the most compelling creation in contemporary poetry — Jim Limber speaks, often, in a voice that blurs the line between his own and McCrae’s. Even without an eye to the biographical synchronicity that, one guesses, must have drawn McCrae to Limber’s figure initially, Limber becomes — in this sequence — a kind of lyric mask: McCrae’s slippery version of a pilgrim-Dante through whom his own authorial-Dante can speak.

“White Yankees think they’re Heaven,” Limber announces in an early poem,

’cause they think

They know how I was treated in the south ’cause

They know how they would treat me if they could

[…]

I yelled when Yankees took me from

Momma Varina she just stretched her arms

Toward me like she was too weak to fight the

Yankees I was kicking them and shouting

Like they was stealing me from home but home’s

Where the white folks who take you take you home

Follows your sorrow so it is like Heaven

These final lines demand careful attention: whether home “follows” sorrow as a dog trails its owner or whether it “follows” like Saturday “follows” Friday remains ambiguous; but the poem remains clear on one front: “home’s / Where the white folks who take you take you.”

“The content of the Comedy is a vision,” writes Auerbach, “but what is beheld in the vision is the truth as concrete reality […] the speaker is a witness who has seen everything with his own eyes and is expected to give an accurate report.” In Sometimes I Never Suffered, this idea applies equally well to Limber.

This sense of authentic reportage — that Limber has actually seen the “long train running ‘round” heaven, that he really did steal the “black blindfold” that heaven’s white inhabitants wear to render invisible the Black inhabitants — leads to an immediacy of feeling that yields, in the reader, an almost unconscious assent to the veracity of the text.

Whether he’s describing the “dead field” just beyond heaven’s gates or the “floppy wolf” that either stands by Jesus or is Jesus, McCrae revels in the world-building that his vision requires:

The gates aint gates it’s dreams but memories

Like dreams the gates of Heaven memories good

Memories and good memories with bad

Parts but the bad parts have been cleared away

And in the spaces where they were

It’s nothing there but light white light but al-

so orange light green light and blue light fall-

ing waterfall blue light but also there

It’s nothing there the spaces where the bad parts

Were they’re the spaces in-

Between the bars the good times are the bars

These lines show McCrae working in his characteristic start-and-restart, hiccup-and-stutter style, which offers itself, formally, as a contemporary analogue — in sense more than syntax — to Dante’s famous terza rima. And, like Dante, McCrae gives these dreams a concrete form that imagistically echoes their intangible content.

These moments add up to a coherent vision — though by “coherent” I don’t mean that they lack in conflict or paradox. At times it can feel as though McCrae works exclusively in the realms of paradox, double meaning, and oxymoronic play. How else to explain a long poem that offers us purgatory before hell and hell as heaven’s immediate predecessor? And how else, we might ask, to tell the story of Jim Limber but through shifting language that pushes past easy resolution?

But McCrae’s penchant for paradox doesn’t amount to self-canceling opposition; rather, it seems, often, like the only way forward after such suffering. Nowhere is this clearer than in “Jim Limber on Continuity in Heaven,” which finds Limber describing how he rides the train that runs in a “perfect circle” around heaven. After noting that “I ain’t suffered at the hands of / Every white man I met and I still under- / stood who was white and who was something white // And altogether black at the same time,” Limber continues:

It wasn’t nothing in the man or me but some-

thing in the life we shared

But I mean share like prisoners

share loneliness I ride the train now like I never suf-

fered on a train sometimes I never suffered in my life

As elsewhere in the book, McCrae wields the paradox of this final phrase — “sometimes I never suffered in my life” — as an avenue toward hope. That Limber did suffer in his life we know by the presence of that “sometimes” but, equally, the “never” creates a moment — a brief eternity — in which Limber is completely free from harm.

McCrae’s capacity for praise may be his most remarkable poetic ability. Rather than yield to the pain, suffering, and injustice that make up much of its world, Sometimes I Never Suffered strains toward a vision of joy. “Heaven’s a horse a train a ship with no / Captain or with a captain but the captain is / A Negro,” says Limber in his penultimate soliloquy, which calls to mind George Herbert’s “Prayer.” The poem ends with a vision of

Ten thousand Negroes cheering you to freedom

A hundred thousand and you got good shoes

And walk to the rowboat smiling and untie it

But Heaven ain’t you running but you staying

There’s joy in these lines — specifically a Black joy — that, paradoxically, manages to redeem heaven. Paradise, Limber tells us, isn’t just being free to “untie” your rowboat — an image of freedom of movement, of choice — it’s being free to decide, for once, not to leave; that is, to “stay” — and to stay, too, in a place where you’re safe.

The final two poems in Sometimes I Never Suffered return explicitly to Dantean territory. Famously, the last word in each section of Dante’s Comedy is the Italian word “stelle,” meaning “stars.” In a sly parallel, McCrae makes this Limber’s last word, too. After describing meeting one of those souls who were “babies when they died […] [who] walk around in sailor hats with blank / Looks on their faces” — another ingenious creation — Limber says:

… when I tried to talk to

Him it was like I wasn’t there

So I peeked in his mouth

and in his mouth was the whole sky and stars

Not only does this final line offer a remarkably coherent cosmic scope, but it also serves as a segue into the book’s last movement — a multipage poem that returns to the hastily assembled angel’s story and finds the angel first building, then climbing the ladder to heaven.

After falling asleep on the seventh rung — an echo of God’s own rest from Creation — the angel dreams that, Jacob-like, he wrestles with God (though in this case his opponent is a sky that “was or was- / n’t God”). After being defeated, the angel wakes up both humbled and relieved. The poem ends:

He opened first one eye and then the other

Sat up and rubbed his eyes then stood and seeing his dream in

The life on the rung he stepped from the rung to Heaven

With these final lines, McCrae leaves us exactly where so much of Sometimes I Never Suffered takes place: with one foot planted firmly on the ladder to paradise and the other caught in mid-air, suspended halfway between heaven and earth.

¤

LARB Contributor

Will Brewbaker studies theology at Duke Divinity School. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in journals such as Narrative, TriQuarterly Review, and Image, among others.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Stronger Than Steel”: On Rowan Ricardo Phillips’s “Living Weapon”

Will Brewbaker picks up “Living Weapon” by Rowan Richardo Phillips.

“To Say Two Things at Once”: On Kathleen Graber’s “The River Twice”

Will Brewbaker wades into “The River Twice” by Kathleen Graber.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!