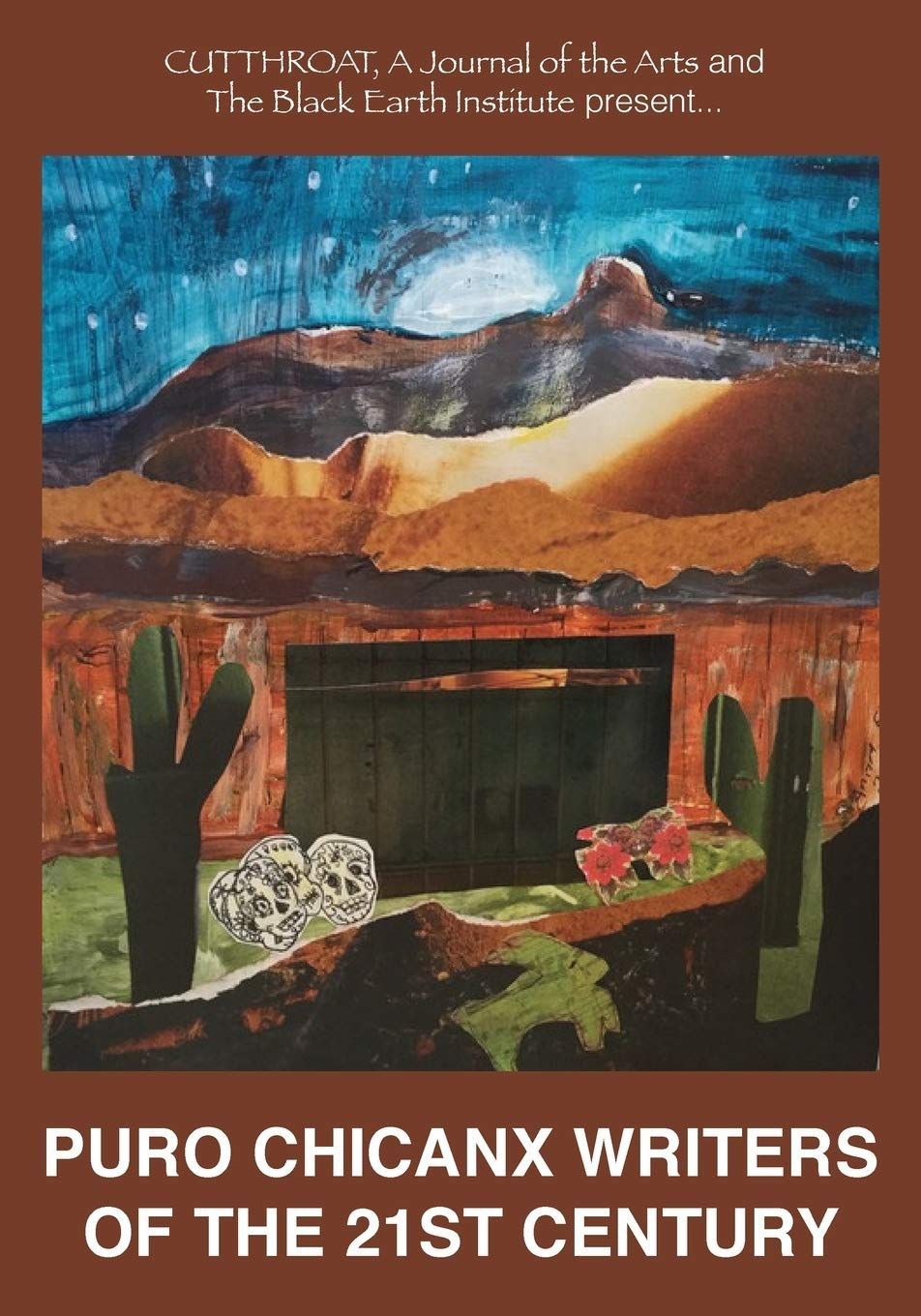

Puro Chicanx Writers of the 21st Century by Pamela Uschuk. Cutthroat, a Journal of the Arts. 358 pages.

“WRITE WITH YOUR EYES LIKE painters, with your ears like musicians, with your feet like dancers. You are the truthsayer with quill and torch. Write with your tongues of fire.”

This was the bold call of writer Gloria Anzaldúa, best known for Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, a pioneering work mixing prose and poetry, myth, and memoir. Her invocation of borderlands — both geographic spaces and psychic ones — reminded us that different cultures cannot be stifled or separated by manmade divisions, but rather they draw strength from the braiding of indigenous wisdom, mestiza consciousness, queer culture, and resistance to colonialism.

Anzaldúa, who died young in 2004, never saw the fruit of her legacy: the blossoming of Chicanx literature by writers who speak with “tongues of fire.” But if she had imagined it, it may well have looked like the anthology from Cutthroat, A Journal of the Arts and Black Earth Institute, Puro Chicanx Writers of the 21st Century.

The book contains poetry, essays, and fiction from 85 authors, ranging from established artists, like American Book Award winner Ana Castillo and San Joaquin writer Gary Soto, author of more than 40 books for adults and children, to newcomers published here for the first time, like poet Bella Alvarez, a freshman at Syracuse University. They carry on many of Anzaldúa’s themes still central to Chicanx experience and culture: racism, immigration, opposition to oppression, family, barrio life, and, still and always, the border.

As poetry editor Carmen Tafolla, the former Texas state poet laureate, explained in an online reading, “These issues are still here, although the details may have changed. We see this collection as a celebration of our people.” Indeed, the many different voices create an ever-changing whole, with surprising components.

Sandra Cisneros, renowned novelist whose The House on Mango Street has sold over six million copies, contributes unexpectedly gritty poems. In “Las Girlfriends,” she writes:

Last week in this same bar,

kicked a cowboy in the butt

who made a grab for Terry’s ass.

How do I explain, it was all

of Texas I was kicking,

and all our asses on the line.

The anthology was conceived by Luis Alberto Urrea, recipient of a 2017 American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature. His own essay in the collection, “That Smell,” describing refugee detention centers, is a scathing indictment of US immigration policy:

What would you do if unknown strangers were paid $750 a day to hold your child in a secret warehouse where she is comforted by concrete and steel. […] Mr. Pence, Mr. Graham, Stephen Miller, Mister President — breathe deep, boys, your legacy will never wash off. You will forever reek.

Urrea proposed the idea to Pamela Uschuk, editor-in-chief of Cutthroat, as a way to resist the politics of hate and empower Chicanx writers. She assembled a talented team of poetry and prose editors and put out a call for submissions. The quantity and quality of work — authentic, profound, and pulsing with energy — shows how timely Urrea’s idea was.

Though the themes are unifying, the voices vary. The pages hold a cacophony of sounds, mixing militant strike calls from Central Valley picket lines, desperate cries of young children ripped from their parents’ arms at the US border, mothers’ humming in kitchens redolent with simmering pinto beans and cilantro, country music blaring from truck radios in south Texas, Santería invocations in botanicas stained with candle wax and animal blood, and cumbia rhythms floating from apartment windows in Los Angeles’s Boyle Heights and San Francisco’s Mission District.

In “Through the Fence,” poetry editor Edward Vidaurre names all the kinds of poems he hears: rosary poems and drum beat poems, tu eres mi otro yo poems, decolonize your soul poems and you were here first poems, Son Jarocho poems and you belong poems. Echoing Anzaldúa, he exhorts, “Stay speaking Spanish, it is poetry / First & last / Breath poems.”

Family is a powerful recurring theme. In “[You take a picture of your father],” Octavio Quintanilla, the poet laureate of San Antonio, writes from a son’s point of view at the moment of his father’s impending death: “he knows. It’s over, and you know it, / hours all you have now after wasting / years in silence […]”

Carmen Tafolla’s “Feeding You” illuminates the role of a mother passing on tradition by slipping chile under her baby’s skin “drop by fiery drop / until it ignited / the sunaltar fire / in your blood.” She tells her child, “I have squeezed cilantro into the breast milk / made sure you were nurtured with the taste / of green life and corn stalks.”

Family is also the theme of “The Disappearing” by debut author Vanessa Bernice de la Cruz. When Socorro, a “Good Daughter,” tries to decide if she should yield to her boyfriend’s coaxing and spend the night with him, she is tormented as she imagines the response from her mother, aunts, uncles, and especially her abuela, “who still thinks being with a guy leads to ruin.” She opts for the boyfriend’s room over a garage, but later sorely misses “the woman who’d taught her to braid her hair before going to sleep every night […] the way she read Neruda while she stood over the stove.”

Racism and oppression on both sides of the border inspire the fury of many contributors. Demetria Martinez, a New Mexico writer who was charged with violating immigration laws when she accompanied two pregnant Salvadoran women across the border in 1986, writes in her piece, “Haiku”:

Still they come, fleeing.

No documents, just rainbows

Folded in pockets

… Still they come, dreaming

Of a land where heads don’t hang,

Bloody, from lampposts.

Genoa Yáñez-Alaniz illustrates the pain of a young woman’s confrontation with racism at a pivotal moment in her life. In “Purity of the Homecoming Dress,” she writes of a high school girl whose school counselor has made it clear that “[w]e cannot masquerade you in a skinny white girl dress.” The racism she faces has deep roots, hidden in the Texas census records, but her mother urges her to resist:

Bring back the survival of escaped esclavos from your past

Draw their spirits through the gifted length of your body

Bind them to the caramel coating of your Mestiza blood

… And thank them.

Some of the snappiest prose comes in short stories about contemporary life in the Chicanx neighborhoods of big US cities. In “Mexican Hat,” Linda Zamora Lucero, the director of Yerba Buena Gardens Festival in San Francisco, transports the reader to a 50th birthday celebration in a Mission District Victorian where, “under a night sky clear as cellophane,” the celebrant is dreaming of a motorcycle getaway to the desert. His wife, who prefers to stay home, plans a bang-up party in the backyard:

Rosie hired Trio Las Hermanas, and like a match to gasoline, they kick the party into high gear with una cumbia. The accordionist in a white leather-fringed vest, cowgirl hat and boots, pumps away, skinny body rocking, facing the white moon. […] In no time, Justina’s raven skirts are flying and Ernie’s wingtips are scratching like a rooster.

Octavio Solis takes us on a journey through El Paso in the minds of Mundo and his friend Louie-Louie, Prince of the Low, in his short story “Mundo Means World”: “It’s a poor man’s therapy for us to drive blind all over town. […] We looked for counsel in the faces of strangers and in the chance graffiti on the walls, the scrambled layers of gang tags, symbols of devotion and fading mercantile signage.”

In “Freckled Like My Skin,” a novel excerpt, Sonia Gutierrez creates a family kitchen so fragrant and homey that the hungry readers will be grateful she included the actual recipe for Elena’s frijoles de la olla.

The key role of tradition — both ancient and modern — is invoked by Matt Sedillo, literary director of the dA Center for the Arts in Pomona. In “Once,” he writes:

We talk history

Mendez and Lemon Grove

Rodriguez vs San Antonio

Saul Castro and the blowouts

McGraw Hill and Texas

How Tucson unified against us.

There are echoes of Anzaldúa’s incantations in his final lines:

How our ancestors walk with us

How our legends rattle our bones

How lucha makes us strong

But la luna makes us who we are.

The reference to Tucson Unified is a nod to a signal moment. In 2012, Anzaldúa’s Borderlands and many other works of Latinx literature were pushed out of the Tucson Unified School District when the Arizona Legislature shut down their successful Mexican American studies program, claiming without evidence that it would incite racial hatred. After a five-year court battle, Judge Wallace Tashima ruled the ban unconstitutional in 2017. What better way to avenge than to publish an anthology of truthsayers writing with tongues of fire?

¤

LARB Contributor

Elaine Elinson is the former editor of the ACLU News and the co-author of Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers, and Poets Shaped Liberties in California (2009), winner of a gold medal in the California Book Awards.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Latinidad in the Age of Trump: On Ricardo Ortiz’s “Latinx Literature Now”

Renee Hudson considers Ricardo L. Ortiz's "Latinx Literature Now: Between Evanescence and Event."

Big Lit Meets the Mexican Americans: A Study in White Supremacy

Latinx novelist Michael Nava considers the unbearable whiteness of publishing.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!