Vast Silences: On Victor LaValle’s “Lone Women”

John Edward Martin reviews Victor LaValle’s “Lone Women.”

By John Edward MartinMay 2, 2023

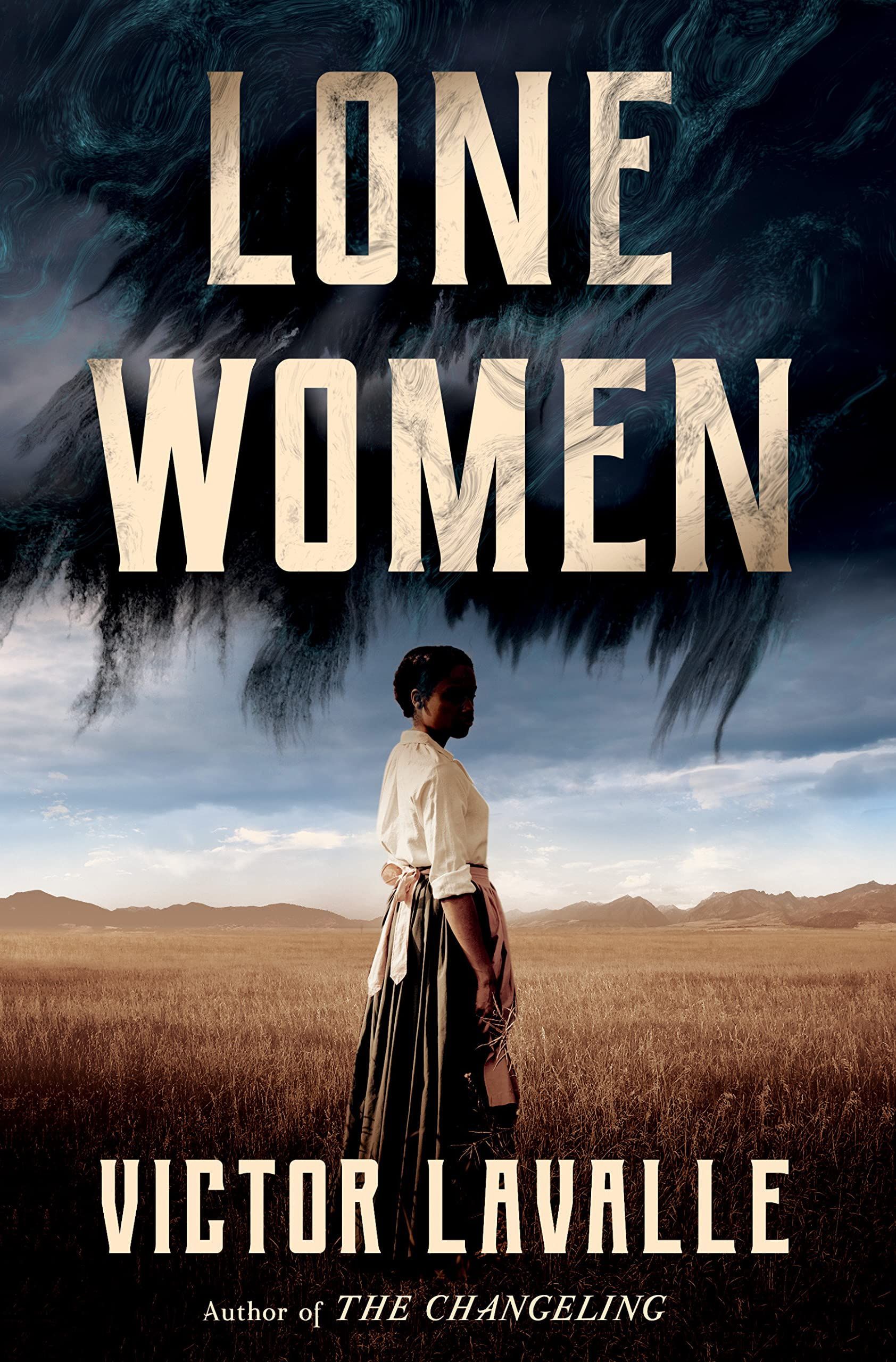

Lone Women by Victor LaValle. One World. 304 pages.

WHEN I LEFT home in the fall of 1990, headed for a university not quite far enough away for my taste, I carried with me one suitcase full of unfashionable clothes, a box of what I considered essential books—mostly reference texts and horror novels—and another of assorted school supplies and toiletries. I figured this was enough to start a new life, to begin crafting the new me that would no doubt emerge from the cocoon of my difficult teenage years now that I had escaped my parents’ house and my working-class neighborhood. Of course, that’s not all I took with me or all that I was escaping. Over the next few years, I discovered other baggage taking up space in my half of a shared dorm room: a lot of anger and resentment, a fair share of trauma, more anxiety and impostor syndrome than I had expected, and a growing awareness of how my identity—Latino, working-class, introverted, and fiercely agnostic—set me apart from and often in conflict with my peers and teachers. All of which is to say that the things we carry with us when we leave home are often heavier than we know at the time.

Adelaide Henry, on the other hand—the protagonist of Victor LaValle’s latest novel, Lone Women (2023)—knows exactly what kind of a burden she carries. “A woman is a mule,” her mother tells her as a child. “My burdens will be your burdens; I am a mule and you will be, too.” At the beginning of the novel, set in the fall of 1915, Adelaide is a 31-year-old Black woman living on a farmstead in California’s Lucerne Valley with her parents, Glenville and Eleanor. They, like many other Black families of the time, came to California from Arkansas to take advantage of federal land giveaways in the West after the Civil War, hoping to make a better life for themselves and their children. Along with 26 other Black families, the Henrys manage to carve out an existence even in the arid climate of the Lucerne by growing alfalfa, feed grass, and Santa Rosa plums. It is a difficult, if more secure, life than they had before, made more challenging by the Henrys’ apparent isolation, even from the other Black families around them: “Queer folk, that’s what they say about the Henrys.”

But queer how? Our first hint comes in the opening pages of the story where we see Adelaide dousing the inside of her family’s farmhouse, including her parents’ dead and brutalized bodies, with gasoline and setting it aflame while reflecting on the “two kinds of people in this world: those who live with shame, and those who die from it.” Which of these Adelaide is destined to be is one of the driving questions of the novel, along with the terrible secrets she carries with her. More literally, Adelaide leaves home that day with $154, a travel bag, and a mysterious steamer trunk containing her “whole life […] [e]verything that still matters.” It is a sentiment felt by many who have left home with only the bare minimum that still mattered.

While fleeing the immediate tragedy, whatever it might be, she is also running from a longer history of toil and sacrifice particular to women, especially Black women, as well as one of loneliness and secrecy specific to her family. It is here that we see some threads of LaValle’s earlier works, which often reimagine American history and its literary traditions from the perspective of people of color to uncover not just their voices and stories, but also their silences and inner lives, their traumas and secrets, which may or may not ever be given voice—at least to those around them. In The Changeling (2017), it is the anxiety of Black parenthood in a world of persistent threats and unseen hostilities. In The Ballad of Black Tom (2016), it is the twin longings for personal agency and collective retribution for historical injustices (and literary ones, if we read his revisioning of Lovecraft’s original 1925 tale, “The Horror at Red Hook,” as such). And in his searing comics series Destroyer (2017), a retelling of Frankenstein, it is personal revenge fueled by the all-too-familiar reality of police brutality and the destruction of Black bodies.

But Lone Women is about a different kind of brutality, one imposed from within as well as from without, and perhaps one particular to women. As her mother warned her, Adelaide must bear a burden inherited by generations of women—that of self-sacrifice for the sake of others. Even as a child, she recognizes the futility and injustice of this. “[T]hat shit wears you down,” she tells us. “The reward for sacrifice is simply more sacrifices.” Leaving home, we learn, does not necessarily relieve you of such an inheritance, even if you burn it down behind you.

Among the few items that Adelaide takes with her is a favorite book—Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848)—a novel about another woman making her way in a patriarchal society that views her as either pitiable or socially deviant, just as Adelaide herself is considered “queer” by those around her. The heroine of that novel, Helen Graham, also flees her home and its history of violence with a young son for whom she must provide safety and a home—in her case by masquerading as a widow and making a living through her art, two things that further alienate her from her society and its mores. What Adelaide must support, besides herself, is the terrible secret locked away in her steamer trunk, though like a child, it has needs and demands that continue to shape her new life.

That new life begins at the Port of Los Angeles aboard a ship bound for Seattle and then a train headed to Big Sandy, Montana, the setting for the bulk of the novel. She is drawn there by a real-life article published in the Great Northern Railway Bulletin of 1913, “Success of a ‘Lone’ Woman,” by Mattie T. Cramer, extolling the virtues and benefits of “homesteading” in the Western United States under the expanded Homestead Act of 1862. That legislation, unusual for its time, allowed for any “head of family” to lay claim to 160 acres (later expanded to 320 acres) in the West, to be cultivated or “proved up” under a contract that would allow full ownership after three years. That vague language, specifying neither race nor gender, created a pathway to ownership for thousands of people previously restricted from owning land, particularly Black families and single, widowed, or abandoned “lone women” (married women were excluded by virtue of not being legally a “head of family”). In fact, lone women were especially encouraged to take up such claims, as they were seen by many in government and business as a potentially “civilizing” influence on these new territories. Women, they believed, would advocate for churches, schools, and safe towns, as opposed to the lawless, dangerous, and immoral vices of earlier mining towns or trading posts. It was the same legislation that first brought Adelaide’s family west to California, but which now offers her an escape from that haunted landscape.

Of course, this would not be a LaValle novel if haunted landscapes were so easy to escape. As Adelaide soon learns, the articles and brochures promoting Montana as a new land of opportunity fail to mention a few other, harsher truths: that this is land that has been “cleared” of its previous residents, Indigenous and immigrant alike, leaving behind their own ghostly traces; that its harsh winters and dry summers make cultivation virtually impossible for a single person, without family or friends to help; and that those who do survive in this environment also carry their fair share of secrets, traumas, and violent histories with them. In that sense, Adelaide fits right in. And yet, she does not—her secret poses a risk to them all.

Before that secret is revealed, though, Adelaide does her best to make a home and, for the first time in her life, to find connections, even friendship, with the people around her. She meets her neighbors, Grace Price and her young son Sam—social outcasts themselves for reasons that we learn later. There is Matthew Kirby, a local cowboy and potential love interest, and his uncle Finn, both seemingly friendly and helpful to a woman living on her own. And finally, another character drawn from history: Bertie Brown, the only other Black resident of Big Sandy, known far and wide for her home brew and the hospitality of her covert gambling room, the Blind Pig. Bertie has secrets as well, including the Chinese woman, Fiona Wong, who shares her cabin and her bed. Each of these neighbors offers Adelaide a chance at a community, free from the judgments of her previous society, but each brings with them the traumas and terrors of their own pasts, and Adelaide must decide if any can be trusted with hers.

Along with these potential friendships, though, there are also potential threats. On her first day in town, Adelaide meets the Mudges—a family consisting of another lone woman traveling with four blind sons who seem at first pitiable, later threatening, and eventually a risk to Adelaide’s own buried secrets. And then there are Jack and Jerrine Reed, the town’s wealthy benefactors, builders of an out-of-place opera house and civic organizers, of sorts. Mrs. Reed is leader of the Busy Bees, a group of women promoting the town and its businesses, or at least its white businesses. Mr. Reed leads a different kind of organization—the Stranglers—a gang of vigilantes who dole out justice on horse thieves, strangers, or anyone else they perceive as a threat to their sense of order. Needless to say, Adelaide and some of her new friends don’t exactly meet the standards of the Reeds’ vision for their community.

All of this serves as the outward setting of a story that is ultimately as much about the inner life, or rather, how the inner life both mirrors and eclipses the outer. Ironically, it is Mr. Reed who first gives thought to this reality as he seeks out Adelaide’s secrets: “As vast as the land could seem, it shrank in comparison to all that he—that anyone—kept within.” A longtime resident of Big Sandy, Mr. Reed knows that Montana, for all its apparent emptiness and openness, is a landscape crowded with spirits and memories, ghost towns and buried bones, monstrous things and monstrous people. But even seemingly respectable people, like himself and his wife, carry all of that and more within, hidden away in the locked trunks or musty attics of their minds. He recognizes in Adelaide another person who contains such vast un-empty silences, though this doesn’t prompt him to sympathize or welcome her presence.

And Adelaide herself comes to feel the magnitude of her own inner life as it begins to manifest, sometimes quite literally, in her body and in the not-quite-empty spaces around her:

Keeping a family secret, one of this scale, the kind of secret that shaped four lives for decades, there is no way to measure the proportions of it within a person’s mind. There is no moment when the secret recedes. It’s a sound that never stops playing in one’s ear; a pain in the body that never quite seems to heal.

When these secrets, her own and those of the people around her, finally begin to emerge, they come fast and furious, driving towards a conclusion that may derive less from the historical record of lone women in the West than from LaValle’s own gothic sensibilities and his imagined histories of those whose stories were rarely recorded. Whether you find that satisfying or disappointing may depend on what baggage you carry and the consequences you imagine in having it torn open for the world to see. Lone Women is not the kind of novel to leave you comfortable with either the silence or the spoken truths.

¤

LARB Contributor

John Edward Martin is the director of scholarly communication at the University of North Texas Libraries, a board member of the Digital Cultural Studies Cooperative, and book review editor of The Edgar Allan Poe Review. He is a scholar of horror literature, film, and comics. His work has appeared in Poe and Women: Recognition and Revision (Lehigh UP, 2023), Deciphering Poe: Subtexts, Contexts, Subversive Meanings (Lehigh UP, 2013), and Fear and Learning: Essays on the Pedagogy of Horror (McFarland & Co., 2013). He holds a PhD in American literature from Northwestern University and an MS in library science from the University of North Texas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Craft Is All the Same: A Conversation with Victor LaValle

Ayize Jama-Everett interviews Victor LaValle about horror and diversity.

Revising Lovecraft: The Mutant Mythos

The mutant legacy of H. P. Lovecraft, as the Cthulhu mythos spawns ever more exotic, challenging revisions.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!