Unearthing Conflict and Complicity: On Kerri K. Greenidge’s “The Grimkes”

Elaine Elinson reviews Kerri K. Greenidge’s “The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family.”

By Elaine ElinsonFebruary 15, 2023

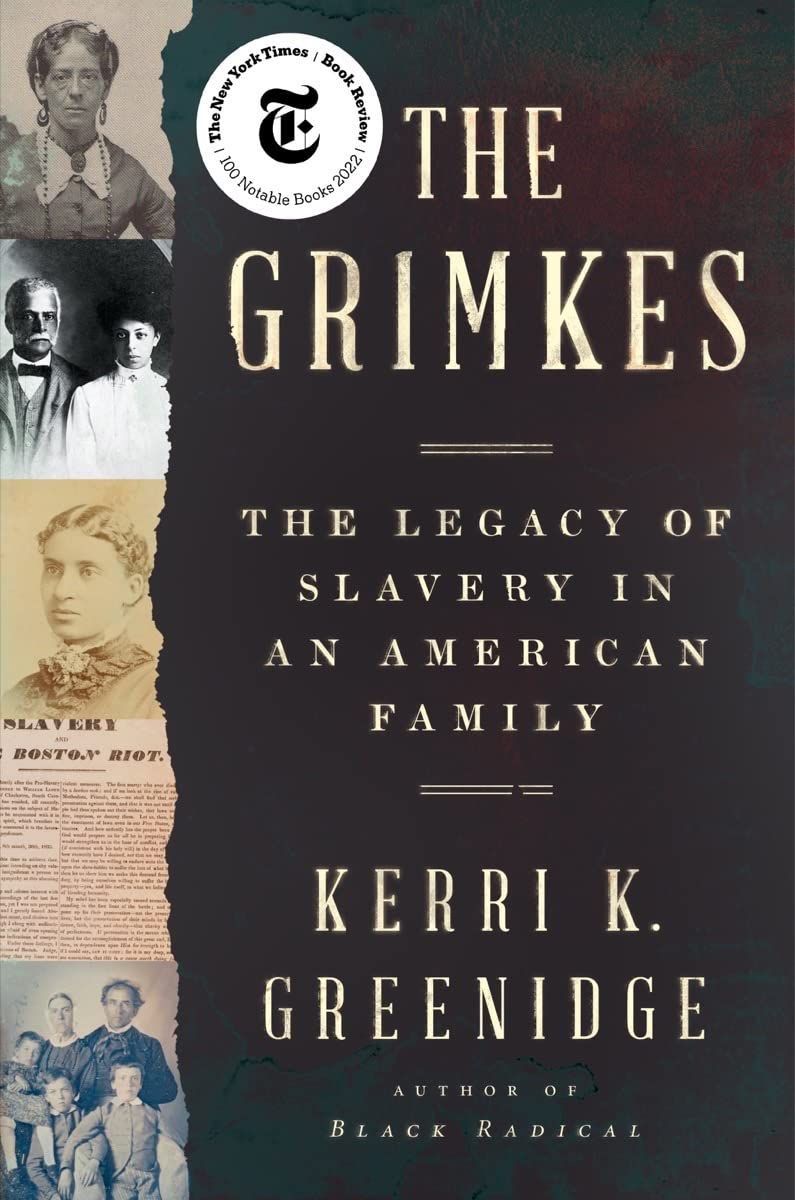

The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family by Kerri K. Greenidge. Liveright. 432 pages.

THE TWO Grimke siblings were born to an enslaved woman and her putative owner. Brutalized by their half-brother, they escaped confinement many times and, with the support of abolitionists in Philadelphia and Boston, went on to educate themselves. The elder graduated from Harvard Law School, wrote a biography of antislavery publisher William Lloyd Garrison, and served as United States consul to the Dominican Republic in Santo Domingo. The younger attended Princeton Theological Seminary and became the minister of a prominent church in Washington, DC.

These are not the Grimke siblings who are lauded in histories of the American abolitionist movement, Sarah and Angelina Grimke. These are their nephews, Archibald (Archie) and Francis (Frank) Grimke, sons of their slave-owning brother Henry and Nancy Weston, the woman he purchased at a slave auction. Their story is not as celebrated as that of their renowned abolitionist aunts.

Kerri K. Greenidge’s remarkable book The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family does much to correct the famous family’s balance sheet. Excavating voluminous archives of slave records, correspondence, articles from the Black and mainstream presses, and speeches, Greenidge, a Tufts University professor, delves into the complexity of the Grimke family with a fresh and illuminating perspective.

Greenidge presents a parallel narrative, shifting the focus from the white abolitionist sisters to the Black Grimkes, descendants of the enslaved and enslavers. This sweeping family saga covers four generations from Charleston, South Carolina, to Philadelphia, Boston, and beyond. With her granular examination of the lives of one multifaceted family, Greenidge reveals how the complex legacy of slavery has haunted American history for generations.

The Grimke family’s brutality was “bred and molded in the rice-drenched slave society of Charleston.” Patriarch John F. Grimke enslaved 700 people, many of whom became the property of his son Henry. The violent cruelty that Sarah and Angelina witnessed on their father’s plantation was deeply etched in their memories and drove them to abandon their comfortable lives in South Carolina to head north, where they became leaders in antislavery organizations.

Greenidge applauds the Grimke sisters’ activism on abolition and suffrage but underscores their shortcomings as condescending white reformers. She notes that the sisters, like most white abolitionist women, could envision the end of slavery, but not equality with Black people. As Greenidge writes,

[They] did not tolerate politically sophisticated, unapologetically opinionated Black abolitionist women who had their own, often radical understanding of liberation. To these white women, Black women were the objects of reform and the embodiment of slavery’s sin, not autonomous architects of Black freedom who were perfectly capable of freeing themselves.

To their credit, when Sarah and Angelina Grimke “discovered” their Black nephews in the pages of the National Anti-Slavery Standard in 1868, they reached out to support their education and introduce them into abolitionist circles. But “[t]he tragedy of the Grimke sisters’ lives was the fact that they never acknowledged their complicity in the slave system they so eloquently spoke against.”

Greenidge does not gloss over the failings of the Grimke brothers either. As they grew to identify with the Black elite, they insisted on bettering the “colored class” at the expense of the “negro masses.” Frank, for example, discouraged poor and working-class Black people from attending the exclusive 15th Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, DC, where he was pastor.

Moreover, when the brothers attained prominence, they downplayed their enslaved past. In press interviews, Archie never mentioned that he had been enslaved and credited his aunts Sarah and Angelina for his acceptance at Harvard and his position as a leader of the NAACP. As children, Archie and Frank were bound in irons, beaten, and starved for the crime of running away, yet these “horrors” of their enslavement “were never mentioned, their pain never acknowledged.” They seem to have embraced the philosophy of Booker T. Washington that “harmony will come […] as soon as we forget the supposed injuries of the past.”

Greenidge includes a helpful “Cast of Characters” at the opening of the book, with thumbnail sketches of several individuals, many of whom are surnamed Grimke. It would have been useful to have an intergenerational family tree as well to show how they were all related.

Though Greenidge puts a spotlight on Archie and Frank, she also introduces some spectacular women in the family. The first is their mother, Nancy Weston, perhaps the unsung hero of this saga, who was purchased as a nursemaid and continuously raped by the brother of the Grimke sisters. Though she kept her own name, she insisted her boys carry the Grimke surname, sheltered them when they escaped the tortures of their half-brother, and found a way to send the teenagers north to New England to be educated. When the white abolitionist families who first took them in forced them to be houseboys instead of scholars, she protested and ensured that they could continue their schooling.

In one of the most poignant passages, Greenidge describes how, after the Union Army marched into Charleston, Weston moved with her youngest son John, and other freed Black women, into the building once used as the region’s slavery auction center. It still contained reminders of the terror, “the auction table that ran the length of the structure; the iron gate with the word ‘Mart’ in gilt letters above it; the adjacent, walled-in yard with the four-story brick prison.” There Weston made a living taking in laundry for the Union Army, including the United States Colored Troops.

Greenidge also describes Frank’s wife, Charlotte (Lottie) Forten Grimke, who was the first Black woman to graduate from the Salem State Normal School in Massachusetts. A brilliant and determined educator, Lottie traveled to the South Carolina Sea Islands to teach Black students. She wrote about her experiences there, becoming the first Black writer published in The Atlantic Monthly. Recognizing “the beauty and dignity of formerly enslaved people, beyond the traumas of slavery and racial victimization described in the abolitionist press,” Lottie joined other Black women in creating their own abolition organizations.

Lottie was also angered and frustrated by the attitudes of white supremacy in the suffrage movement. As Martha S. Jones details in Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (2020), leading white suffragists opposed granting the vote to Black men if women were not included. Elizabeth Cady Stanton stated that Black male suffrage was an “open, deliberate insult to the women of the nation” and called on her critics to imagine “Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Ting who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic” making laws for women.

Stanton’s racist statements drew a sharp rebuke from Black suffrage leader Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who concluded that “faith in white goodness could never lead to the type of liberation that Black women demanded.” Lottie joined Watkins Harper in the postbellum Black women’s rights movement that “placed racial equality and Black liberation at the center of women’s suffrage.”

Finally, Greenidge profiles Angelina (Nana) Weld Grimke, Archie’s daughter, who was raised by Uncle Frank and Aunt Lottie after her mother died. Though she was taught to “exalt the self-righteous antislavery of her white Grimke ancestors rather than the lives of the Black family they enslaved,” Nana came to represent a new generation of Grimke descendants who were finally able to bear witness to a century’s worth of racial trauma.

The rebellious Nana bristled at her father and uncle’s elitism. As Greenidge writes,

Nana felt the hollowness of the politically impotent colored elite who, though committed to anti-lynching legislation, enfranchisement, and uplift of the “negro masses,” often reenacted on themselves and their community the very racial system that caused all Black people such harm.

A gifted writer who resented the restrictions on her own passions and personal ambitions, Nana became a celebrated poet and playwright of the Harlem Renaissance. Her play Rachel (1916) was produced by the NAACP as a refutation of D. W. Griffith’s Klan-glorifying Birth of a Nation (1915). Her work eventually “provided expression for the existential rage of a colored elite that was never allowed to express its anguish over the racial maelstrom in which they lived.”

Greenidge notes that while white reformers might have disavowed “their complicity in America’s racial project […] Black descendants rarely enjoyed the privilege of ignoring history.” Thanks to her tenacious scholarship, a much clearer picture of that history is unearthed and put into focus.

¤

LARB Contributor

Elaine Elinson is the former editor of the ACLU News and the co-author of Wherever There’s a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers, and Poets Shaped Liberties in California (2009), winner of a gold medal in the California Book Awards.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Which Way the NAACP: On A. J. Baime’s “White Lies” and Tomiko Brown-Nagin’s “Civil Rights Queen”

Randal Jelks considers two books about underappreciated Civil Rights figures, A. J. Baime’s “White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White and...

Calling on Lincoln

Ronald White considers “A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House” by Jonathan W. White.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!