This piece appears in the Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal: Catharsis, No.25

To receive the Quarterly Journal, become a member or purchase at our bookstore.

¤

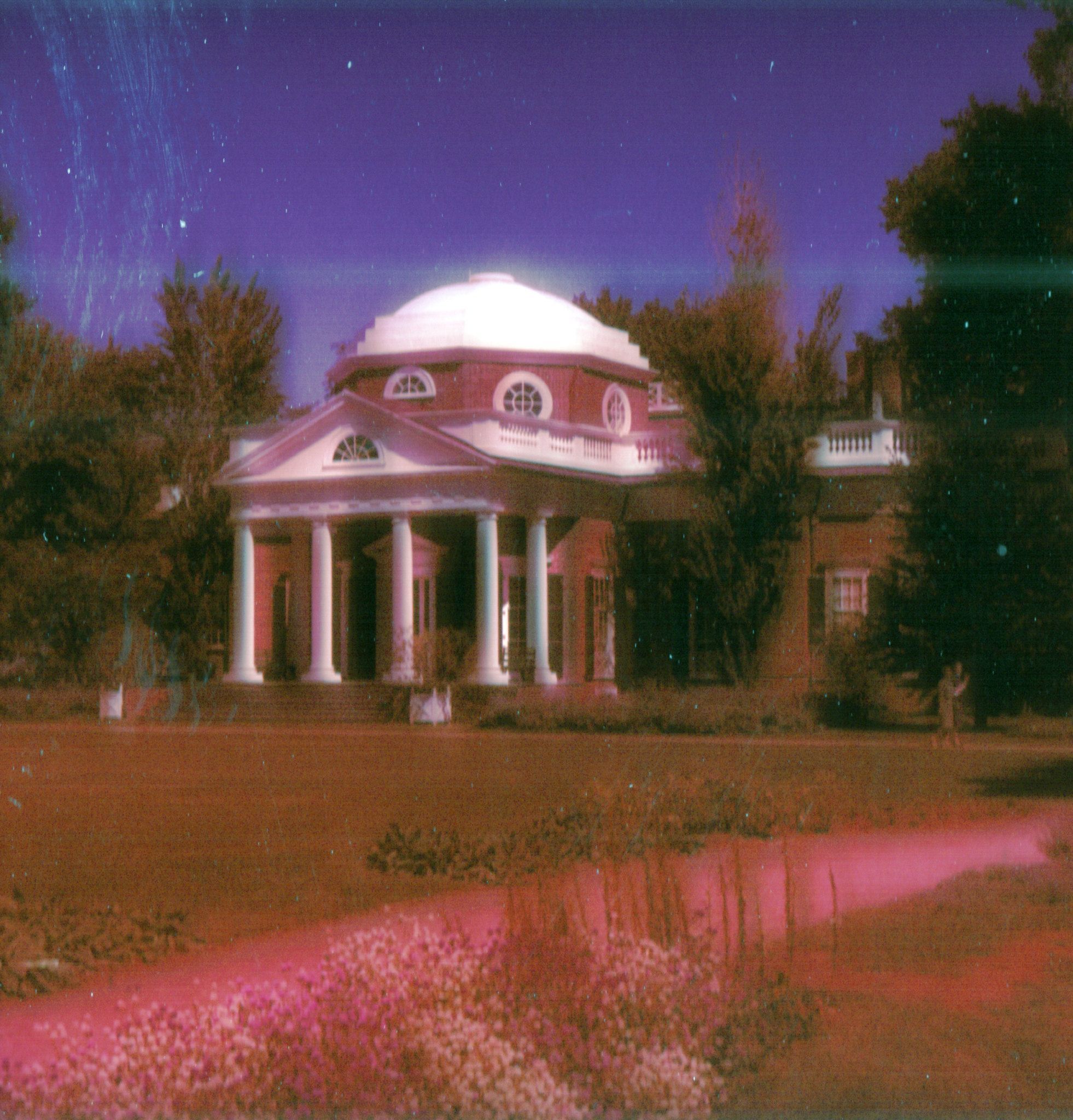

Terrorem

Every night, I go back to Mr. Jefferson’s place, searching still

his kitchens, behind staircases, in a patch of shade somewhere

beside his joinery & within his small ice house, till I get down

that pit, lined with straw, where Mr. Jefferson once stacked frozen slabs

of river water until summer. Then, visitors would come to him

to ask about a peculiar green star, or help him open up

his maps. They’d kneel together on the floor, among his books

lavish hunks of ice melting like the preserved tears

of some antique mammal who must have wept

to leave Albemarle, just as I wept when I landed in Milan

for the first time, stone city where Mr. Jefferson began

to learn the science of ice houses, how you dig into the dark

flank of the land, how you seal the cavity. Leave open

just one small hatch through which I might lift, through gratings

Mr. Jefferson’s cold dressed victuals, his expensive butter & salads

the sealed jars sweating clear gems of condensation, white blood

appearing from warm air, as if air could break & slough, revealing

the curved arc of our shared Milan. There, I wore silver rings

on each thumb. I studied & spoke in fine houses

of ice. I knew a kind of crying which sealed me to such realms

for good. Old magic weep, old throb-in-throat. How much

of my fondness for any place is water, stilled & bound

to darkness?

¤

Farm Book

Whenever I write about Mr. Jefferson, he gallops

over. Knock knock, he begins in quadruplicate. It’s

pretty wild, like my student’s poem about a house

of skin & hair, a house that bleeds. Mr. Jefferson’s

place is so dear to me, white husk my heart beats

through, until I can’t write more. In my student’s

poem, the house stands for womanhood, pain coiled

in the drywall. Sorrow warps the planks, pulling nails

from ribs. In Kentucky, I’m the only black teacher

some of my students have ever met, & that pulls me

somewhere. I think of Mr. Jefferson sending his field

slaves to the ground, a phrase for how he made them pull

tobacco & hominy from the earth, but also for how

he made of the earth an oubliette. At sixteen, they went

to the ground if Mr. Jefferson thought they couldn’t learn

to make nails or spin. He forgot about them until they

grew into cash, or more land. For him, it must’ve seemed

like spinning. Sorrow of souls, forced to the ground

as a way of marking off a plot. At sixteen, I couldn’t

describe the route to my own home, couldn’t pilot

a vehicle, could hardly tell the hour on an analog

clock. I had to wear my house-key on a red loop

around my neck. Now, I rush to class beneath a bronze

Confederate, his dark obelisk, his silent mustache. My books

tumble past the lectern as I recite Mr. Jefferson’s litany: Swan.

Loon. Nuthatch. Kingfisher. Electric web of names, yet

in the ground, I know, a deeper weave of gone-away ones

who should mean more to me than any book. I live in language

on land they left. I have no language to describe this.

¤

LARB Contributor

Kiki Petrosino is the author of four books of poetry: White Blood: a Lyric of Virginia (forthcoming, 2020), Witch Wife (2017), Hymn for the Black Terrific (2013), and Fort Red Border (2009), all from Sarabande Books. She holds graduate degrees from the University of Chicago and the University of Iowa Writer’s Workshop. Her poems and essays have appeared in Poetry, Best American Poetry, The Nation, The New York Times, FENCE, Gulf Coast, Jubilat, Tin House, and online at Ploughshares. She teaches at the University of Virginia as a professor of Poetry.

LARB Staff Recommendations

From "The Nature Book": A Literary Supercut

An excerpt from "The Nature Book" by Tom Comitta, a literary supercut of nature descriptions from 300 novels by Arundhati Roy, Don DeLillo, and more.

The Amazing Bicentennial Girl

Deborah Taffa on growing up Native American during the U.S. Bicentennial

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!