The Two Abysses of the Soul

Costica Bradatan shows us how The Brothers Karamazov explains Russia's current politics.

By Costica BradatanJuly 31, 2014

For Ion Ianoși, from whom I learned how to love Russia.

¤

WHEN RUSSIA AMPUTATED CRIMEA from Ukraine earlier this year, expertly swift as the stroke was, the pain was not just local. It was felt right away throughout Eastern Europe, from Warsaw to Bucharest to Vilnius to Riga. Indeed, this was a pain that brought back the memory of older, bigger wounds, which people in the region thought they had safely forgotten about. Always an aggressive, expansionist neighbor, the Russian bear, whenever it had the chance, didn’t hesitate to swallow up, in whole or in part, smaller neighboring countries. Little wonder that the latter ended up perceiving Russia as nothing but a realm of destruction. Joseph Conrad, who experienced the Russian empire’s insatiable land hunger firsthand, in his native Poland, openly regarded it as an empire of nothingness. In “Autocracy and War” (1905), for example, he wrote that from Russia’s inception “the brutal destruction of dignity, of truth, of rectitude, of all that is faithful in human nature has been made the imperative condition of her existence.” Under the oppressive shadow of Russian autocracy “nothing could grow.” Some eight decades later, in “The Tragedy of Central Europe” (1984), Milan Kundera would make a similar point: when Russians brought totalitarianism to his country “they did everything possible to destroy Czech culture.” Indeed, for him, “totalitarian Russian civilization is the radical negation of the modern West.”

Vladimir Putin’s sudden decision to start slicing up Ukraine must have reminded East Europeans of Russia’s traditional expansionism, but also of something else, something even worse. For there are still vivid in Eastern Europe’s collective memory episodes of Russian brutality so ferocious, so nightmarish that they can’t have anything to do with politics, not even with its most cynical variety. No matter how you look at them, even within a logic of repression, these acts just don’t make sense; they are too extreme to serve any punitive or preventive function — or any other rational purpose, for that matter.

Two such episodes stand out. One occurred in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-1933, when the Soviet authorities staged an artificial famine of enormous proportions. In a recent book, Bloodlands, Yale historian Timothy Snyder estimates that approximately 3.3 million people died then of starvation. (Some three millions were ethnic Ukrainians; the rest were Russians, Poles, Germans, and Jews.) How was this done? First, when the peasants could not meet the excessively high quotas of grain set by Moscow, all their food supplies were confiscated. “The authorities searched for that grain as if they were searching for bombs and machine guns,” writes Vasily Grossman, whose book Everything Flows offers one of the most compassionate accounts of the Ukrainian famine. Everything edible was taken away by party activists and OGPU (Soviet security services) officers. Their entire seed fund was seized; even cooked food, dinner already set on the table, was swept away.

Once that was done, people were left to die the slowest of deaths: “The village was left to look after itself — with everyone starving in their huts. […] And all the various officials from the city stopped coming.” To make sure nobody escaped, roadblocks were set up by the OGPU, and the railway stations were guarded by armed soldiers. Through Party and OGPU channels, Stalin was kept abreast of what was going on. In their naïveté, some Ukrainian party members even wrote him a letter, asking: “How can we construct the socialist economy when we are all doomed to death by hunger?” But Stalin saw the starvation as a trick used by “Ukrainian nationalists” to undermine the Soviet economy, and demanded more food exports. “It is imperative to export without fail immediately,” he said.

“Death by hunger” is a degrading death. You don’t just die — before you do so you regress to an animal state. When no dogs and cats were to be found, people turned to mice and rats. When there was absolutely nothing left to eat, they started eating each other. The local OGPU officers reported with clinical accuracy: “families kill their weakest members, usually children, and use their meat for eating.” Authorities sentenced people for cannibalism, but did nothing to stop the starvation. They moved in only when nothing was moving. Grossman describes the end of the famine in one village:

There was no wailing — no one left to wail. I learned later that troops were sent in to harvest the winter wheat — but they weren’t allowed to enter the dead village. […] They were told that there’d been an epidemic. They kept complaining, though, about the terrible smell from the village.

Throughout Eastern Ukraine, where most of this took place, settlers were brought in (ethnic Russians to replace the dead Ukrainians), but no matter how hard they washed and rubbed those walls, the smell of death would just not go away. Why were these people starved to death? In a sense, just because.

The other episode occurred in 1940, when some 21,892 Polish prisoners (Snyder’s number) were murdered in the Katyn Forest, near the Russian city of Smolensk, by the NKVD (the new acronym of the Soviet secret police). The massacre was approved by the Soviet Union’s Politburo, whose members were all in Stalin’s pocket. At the time, Poland was a country badly damaged, divided between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Many victims were career officers of the defeated Polish army, while others were drafted reservists who represented Poland’s scientific, cultural, and political elite. Some of them chose to surrender themselves to the Soviet army to avoid capture by the Nazis. They were never accused of, or tried for, anything; certainly, they didn’t expect to be executed. When they were taken away to be shot, they celebrated — they thought they were being released. The killings were performed individually: two NKVD officers would hold the victim by the hands, while a third would shoot him in the head, from behind. One victim at a time, some 21,892 times. Why did they kill unarmed, defenseless prisoners like this? Just because.

“Just because” — that’s what defines these episodes. They are enormously brutal, gratuitous, and incomprehensible. They seem to emerge from some dark corner of human nature: no matter how intently we scrutinize it, we cannot make anything out.

¤

Toward the end of The Brothers Karamazov, as the prosecutor Ippolit Kirillovich makes his case for Dmitri Karamazov’s condemnation, he brings up the image of two abysses between which the defendant, in his view, is caught. One is the “abyss beneath us, an abyss of the lowest and foulest degradation,” while the other is “the abyss above us, an abyss of lofty ideals.” “Two abysses, gentlemen,” says the prosecutor, “in one and the same moment — without that […] our existence is incomplete.”

This image of the two intertwined abysses can be said to be a picture of Russia itself. The basest and the highest, the most despicable and the noblest, profanity and sainthood, total cynicism and winged idealism, all meet here. Andrei Tarkovsky has an uncanny ability to articulate this synthesis of opposites into a mystical vision of sorts — most of his films take the viewer from the depths of a dark, corrupted world all the way up to a realm of splendors and a vision of beatitude. In Andrei Rublev that happens literally as, at the end of the film, you are led from a black-and-white “vale of tears,” all mud and blood, to the serene contemplation of Rublev’s divine images, all in full color now. Outsiders may find this hard to take, but for a Russian sensibility such a transition is a natural movement. There is no break here, just the normal traffic between the two abysses of the soul.

Since the two abysses cannot be disjointed, along with the abyss of Katyn and of the Ukrainian famine, East Europeans get to know intimately the other one as well: the abyss of “lofty ideals” — of Russian literature, music, cinema, philosophy, and religious thought. Stalin has marked Eastern Europe forever, but so have Dostoevsky, Shostakovich, Tarkovsky, and Shestov. Historically, Russia has caused much suffering in the region, but it has also shaped people’s minds and affected their sense of being in the world. Russia’s cultural proximity has translated for East Europeans into an expanded repertoire of feelings, sensibilities, and states of being. In the long run, the situation has no doubt enriched — philosophically and existentially — the East European cultures.

This may be history’s ironic payback, some perpetual war reparation program. With one hand Russia gives slaps, with the other it makes presents. Krzysztof Kieślowski, to give one example, felt the intensity of both. Like many a Pole, he resented and complained about Russia’s negative role in his country’s history. At the same time, however, he was influenced by, and greatly admired, the cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky, and he was able to understand the latter’s films as deeply as he did precisely because he came from a place that was culturally under Russia’s sway. Kieślowski may have not spoken Russian, but he spoke the same existential language as Tarkovsky.

To be sure, Russia had its own share of Katyns in the 20th century: under Stalin, millions of Russian lives were destroyed in political prisons and labor camps for no obvious reason. Some of those who returned wrote about what they went through, which has given rise to one of the most characteristically Russian of literary genres: “Gulag literature.” What these writers stumbled upon in Siberia was a relatively new province of the human experience. (Stalin’s camps were an inspiration for Hitler’s.) In the Gulag, humans were brought to the zero level of their existence, and to articulate a vision of the human condition as seen from that particular angle was the privilege of these authors, a privilege for which they paid the heaviest of prices.

Varlam Shalamov, who spent some 17 years in the camps, writes in his Kolyma Tales: “at the age of 30 I found myself in a very real sense dying from hunger and literally fighting for a piece of bread.” The task that he, along with other Gulag writers, sets himself is precisely to map out these gray areas where humanity dissolves into inhumanity. The job is tremendous because you have not only to live in hell with some dignity, but also to write about it with a certain degree of compassion, which under the circumstances is next to impossible. “All human emotions,” says Shalamov, “love, friendship, envy, concern for one’s fellow man, compassion, longing for fame, honesty,” all of them “had left us with the flesh that had melted from our bodies during our long fasts.” The camp was a “great test of our moral strength, of our everyday morality, and 99 percent of us failed it.” These places “do not permit men to remain men; that is not what camps were created for.”

It may well be because East Europeans have known Russia’s abyss of the “lowest and foulest degradation” so intimately that they are in a good position to look into its abyss “of lofty ideals.” Having survived the Russian tanks, or secret police, or brainwashing, you are placed in an ideal situation to understand the greats of Russian letters. That may explain why Varlam Shalamov, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Eugenia Ginzburg, and other authors of camp literature have been some of the best-received Russian writers in Eastern Europe. They describe states of being and limit-situations that East Europeans have known, too. The latter, too, have been there, whether actually or vicariously. Herta Müller may have never spent time in the Gulag, but she writes as if she has. In The Hunger Angel, she identifies herself with the camp dwellers so completely that her novel seems to come straight out of Siberia. “Never was I so resolutely opposed to death as in the five years in the camp,” says The Hunger Angel’s narrator-hero. “To combat death you don’t need much of a life, just one that isn’t yet finished.” This may well have been uttered by Shalamov himself.

¤

There are works of literature that transcend aesthetics, literary history, and craftsmanship, and give us access to something deeper and more consequential. These works are no longer about their individual authors: through them something important about the collective psyche is captured and given expression. Don Quixote is one such work. Miguel de Unamuno thought that Cervantes’s novel was nothing less than the autobiography of Spain itself. Thomas Mann wanted his Doctor Faustus to be read in the same spirit. He hoped that, by writing this book, he would find out what exactly — in Germany’s history, culture, and philosophy — could bring forth something as monstrous as Nazism. The Brothers Karamazov, too, must be such a work. One feels compelled — especially when one comes from Eastern Europe, which has had its share of brushing with the two abysses of the Russian soul — to look into Dostoevsky’s novel for answers to bigger questions about Russia’s history and presence in the world.

Much of what is going on in the novel is highly symbolic, each of the brothers representing a different facet of Russia. At one point Alyosha Karamazov says of Ivan, his brother: “There is a great and unresolved thought in him. He’s one of those who don’t need millions, but need to resolve their thought.” Ivan stands in for Russian philosophy itself — aren’t Russian philosophers almost always on a quest to “resolve their thought”? Whether you read Chaadayev, Solovyov, Rozanov, Berdyaev, or Shestov, you always sense an unbearable tension, a barely contained drama, in their thought. The hubris of Ivan’s thinking, the boldness of his rebellion, the intensity with which he poses the “accursed questions” — they are not only his, but also Russian philosophy’s at its best moments. With his “Legend of the Grand Inquisitor,” Ivan Karamazov marked philosophy, in Russia and elsewhere, like no other fictional character, apart from Plato’s Socrates, ever has.

And isn’t Alyosha himself representative of Russian spirituality? The theology of beauty and embodiment, the mysticism of the earth, the spiritual function of humility and holy foolishness — they belong to Alyosha as much as they do to Russia’s great religious figures, from Leo Tolstoy to Pavel Florensky to Andrei Tarkovsky. Alyosha has an “angelic” function in the novel, always carrying messages, always hurrying somewhere, bringing people together, trying to reconcile opposites. Moreover, we have access to Father Zosima’s theological ideas through Alyosha: he gives Zosima a “voice,” and the two characters merge in the end, master and disciple becoming one.

Dmitri Karamazov is the face of ordinary Russia. The prosecutor who sends him to Siberia says as much. “She is here, our dear mother Russia, we can smell her, we can hear her!” As Russians, “we are lovers of enlightenment and Schiller, and at the same time we rage in taverns,” he says, “an amazing mixture of good and evil.” Dmitri is impulsive, but noble; naive, but also ready to sacrifice himself; he acts stupidly, but always generously; he is ready to kill his father for money, but is never petty; he habitually gets drunk on poetry and liquor, quite unable to separate the two forms of drunkenness. He ends up badly framed, as ordinary Russia always does.

The high point of a symbolic reading of The Brothers Karamazov, however, is the lackey Smerdyakov. To many readers this may seem surprising: in the novel, his is one of the most washed-out faces. We can’t really “read” Smerdyakov. He may or may not be Fyodor Pavlovich’s bastard son (and thus one of the brothers Karamazov); he is inconspicuous, elusive, slippery, always hiding, always doing things on the sly. What’s remarkable about him is that he is so unremarkable. And yet behind this mask of anonymity there lies something frightening: a compulsion to do evil for its own sake. When Smerdyakov is introduced, we learn of him that “as a child he was fond of hanging cats and then burying them with ceremony.” Why did he kill the cats? Just because. As he grows up he gets better and better at gratuitous evil. Now an adult, Smerdyakov teaches kids in the neighborhood a certain trick: “take a piece of bread, […] stick a pin in it, and toss it to some yard dog, the kind that’s so hungry it will swallow whatever it gets without chewing it, and then watch what happens.” Why torture the dogs? Why not? Eventually Smerdyakov develops this into a systematic, coherent behavior. He kills Fyodor Pavlovich without any clear motive; he plans the murder to the last detail and commits it in cold blood, but we don’t know why. He kills just because.

Smerdyakovism is an obscure, yet tremendous force that runs deep throughout Russian history. Its basic principle is formulated succinctly by the lackey himself: “The Russian people need thrashing.” Why? Just because. Smerdyakovism flares up especially in the form of leaders and institutions that rule through terror alone; repression for the sake of repression. Its impact is overwhelming, its memory traumatic, and its social effects always paralyzing. Joseph Conrad sees “something inhuman,” from another world, in these Smerdyakovian institutions. The government of Tsarist Russia, relying on an omnipresent, omnipotent secret police, and “arrogating to itself the supreme power to torment and slaughter the bodies of its subjects like a God-sent scourge, has been most cruel to those whom it allowed to live under the shadow of its dispensation.” And that was just the beginning.

It was Stalin who brought Smerdyakovism to perfection. Under his rule, Smerdyakov starved to death millions of Ukrainian peasants and killed tens of thousands of Polish prisoners. In Siberia he built a vast network of camps and prisons whereby a significant part of Russia’s population was turned into slave labor. All this for no particular reason — just because. In The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn documents the whole thing in maddening detail. The Great Terror that Stalin orchestrated and put into practice with the help of the NKVD in the late 1930s is perhaps the most eloquent example of Smerdyakovism in 20th-century Russia. Without any trace of rational justification, the country’s artistic, scientific, political, and military elites were decimated within a few years. Some of its best writers, scientists, engineers, and generals received then a bullet in the head. Among them was Pavel Florensky (1882-1937), philosopher, theologian, mathematician, physicist — one of the greatest minds Russia ever had, often called the “Russian da Vinci.” And so was Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938), one of its finest poets. But maybe we should not be surprised that Stalin killed poets: after all, Smerdyakov never liked poetry. “Verse is nonsense,” “who on earth talks in rhymes?” he complains. “Verse is no good.”

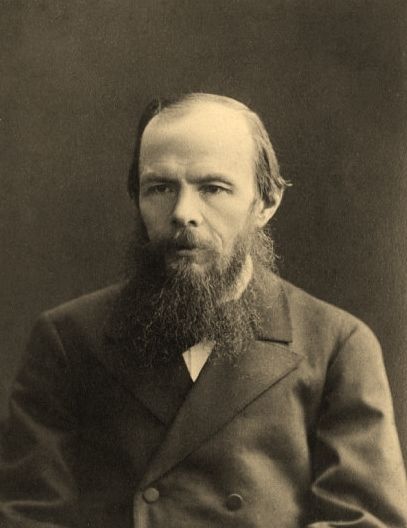

The more fascinating the philosophical vistas opened up by The Brothers Karamazov, the more puzzling its author. Dostoevsky is a complicated case. As a creative artist, he is as insightful as it gets. He has given us access to regions of the human soul that few before or after him have. He is bold, visionary, and uncannily prophetic. As a novelist, Dostoevsky is a most generous demiurge: each of his novels emerges as a universe in its own right, a polyphonic world where characters have their distinct voices, independent from their author’s. Yet as a journalist Dostoevsky can be embarrassing. He was narrow-minded, often mediocre, and parochial, when not openly xenophobic and anti-Semitic. This Dostoevsky — the nationalist, the inveterate Slavophile for whom Russia was a “God-bearing country” that had some natural right over others — would have likely approved of Putin’s efforts to save Ukraine from the paws of the godless West. Ever since he died Dostoevsky has not ceased to supply Russia’s political establishment with ideas, one fancier than the next.

We should not be so surprised, though. For that, too, is in The Brothers Karamazov. Throughout the novel, Ivan toys with the idea that "if God does not exist, then everything is permitted." He drops it carelessly in conversations so that any idiot can pick it up and use it. Then, one day, Smerdyakov tells him that he just used it to murder his father. The killing “was done in the most natural manner, sir, according to those same words of yours,” says the lackey, barely containing, we surmise, sardonic laughter. Smerdyakov is of course lying — he killed Fyodor Pavlovich just because — but his mockery of Ivan’s idea is real. Mocking philosophical ideas is another facet of Russia.

¤

Putin’s spin doctors are always ready to connect his politics to a line of Slavophile thought that runs deep in Russia and leads straight to Dostoevsky himself. Indeed, Putin is often seen crossing himself in the presence of Orthodox clergy and lighting candles in the midst of pious, simple Russian folk. Cameras are always close at hand to capture his churchgoing, just as they are to seize his tiger hunting, horse riding, crane saving, reindeer feeding, topless fishing, tank driving, or jet flying. Putin must be laughing like mad at Dostoevsky’s Slavophilia, just as Smerdyakov was laughing at Ivan’s philosophy. For Putin cares as much about ideas (Slavophile or otherwise) as he does about the tigers he kills.

Putin can be a politician, a thinker, a hunter, a fisherman, a hockey player, a fighter pilot — he can be anything he likes because he is nothing in particular. “He is an excellent imitator,” writes Anna Politkovskaya. “He is adept at wearing other people’s clothes, and many are taken in by this performance.” Journalists have often noticed how difficult it is to “read” Putin, since he is always so slippery. Yet for any serious reader of The Brothers Karamazov this is something familiar. Featurelessness itself can be a feature — that’s one of the indications that you are in Smerdyakov’s presence.

Putin, too, is Smerdyakov. The institution that created him (the KGB) is one of the most Smerdyakovian institutions ever devised. His unapologetic defense of the Soviet Union and his attempts to revive it, his recycling of the Stalinist propaganda machine, the silencing of human rights movements all over Russia, the manner in which he annihilates his opponents — all are signs that Smerdyakovism enjoys a new life in today’s Russia. Most significant of all, however, is Putin’s recent vivisection of Ukraine; Smerdyakov’s signature is all over it. An army of faceless, nameless, insignia-less “little green men” who steal themselves into the country under the cover of night and, before anyone knows it, cut off a piece of it. Since they do everything on the sly, and the whole operation looks more Mafia-like than military, people liken Putin’s army to a gang of thugs. That’s inaccurate: the “little green men” are not thugs, they are Smerdyakovs in action. There is nothing fake about them; their modus operandi is the lackey’s 100 percent.

To be sure, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin is not Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin. They are both Smerdyakovian, but, by its very nature, Smerdyakovism is protheic, multidimensional, complex. Stalin’s Smerdykovism manifests itself especially in his “just because” acts, while Putin’s in his anonymous, cowardly mode of operation. But that’s little consolation to an Eastern Europe traumatized for centuries by its stronger, always erratic, always drunk-like neighbor. For these countries the danger does not necessarily come from Putin or Stalin personally, but from Russia’s timeless Smerdyakovism, of which they are only temporary embodiments.

Politically, the tragedy of Eastern Europe comes from the fact that its security ultimately depends on what happens in Russia. Here political legitimacy is produced not through ordinary democratic practices, but through fabricated crises, at home and especially abroad. Putin has staged the farce of free elections several times already; he’s had his fun, but must be tired of it. At the same time, as he well knows, to stay in power he can’t rely on photo ops alone, no matter how lowly they get. Having made a mockery of democracy, Putin has reached a point where only inventing conflicts and invading countries could bring him what, in Russia, passes for political legitimacy. That’s true of the Smerdyakov who rules Russia now, as it is of those who will rule it in the future.

Eastern Europe, then, is stuck. Stuck indefinitely not only in Russia’s dangerous proximity, but also between the two abysses of the Russian soul.

¤

Costica Bradatan is an associate professor in the Honors College at Texas Tech University and the religion/comparative studies editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books. His most recent book is Dying for Ideas: The Dangerous Lives of the Philosophers.

LARB Contributor

Costica Bradatan is a professor of humanities in the Honors College at Texas Tech University in the United States and an honorary research professor of philosophy at University of Queensland in Australia. He is the author and editor of more than a dozen books, including Dying for Ideas: The Dangerous Lives of the Philosophers (Bloomsbury, paperback, 2018) and In Praise of Failure: Four Lessons in Humility (Harvard University Press, 2023). His work has been translated into more than 20 languages, including Dutch, Italian, Turkish, Chinese, Vietnamese, Arabic, and Farsi. Bradatan also writes book reviews, essays, and op-ed pieces for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Times Literary Supplement, Aeon, The New Statesman, and other similar venues.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!