Turn Left or Get Shot

Priyanka Kumar on Elizabeth Hinton's "From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime."

By Priyanka KumarSeptember 24, 2016

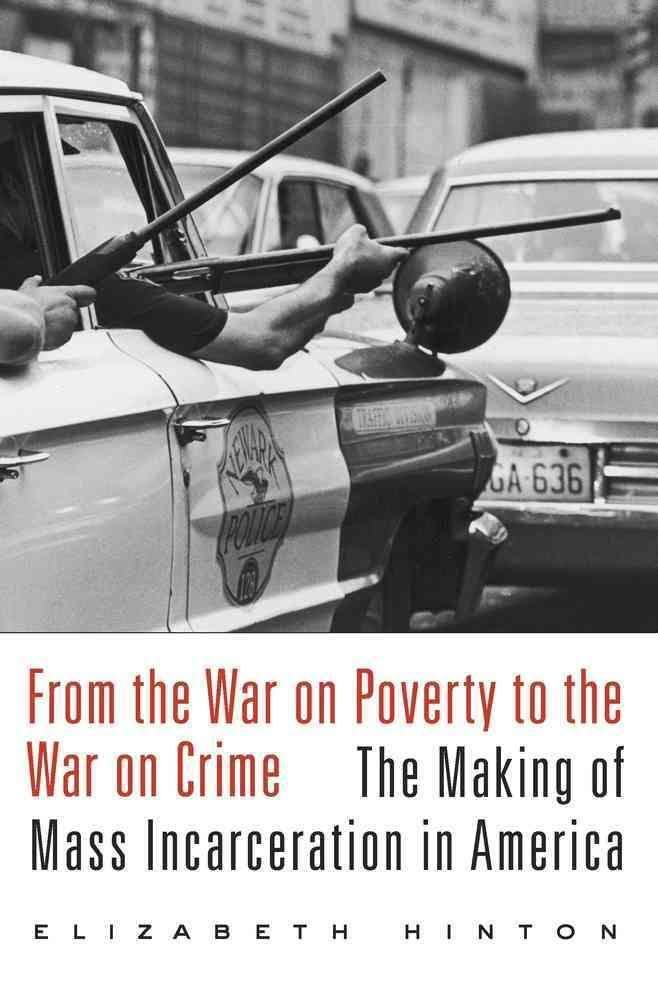

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime by Elizabeth Hinton. Harvard University Press. 464 pages.

THE LEGENDARY BIOLOGIST E. O. Wilson once said: “We are drowning in information, while starving for wisdom.” While we are not exactly drowning in information on how government policy, racial profiling, and systemic mass incarceration have worked in concert to exacerbate racial tensions in the United States, there is now a wealth of such analysis available, and one has to wonder how and when wisdom will infiltrate policy in a meaningful way.

It is well known that, with over two million people in prison, the US has a disproportionately high prison population compared to other developed countries. In addition to providing an ethical imperative to downsize, Elizabeth Hinton gives us an economic one in her recent book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America, pointing out that the prison system costs American taxpayers $80 billion annually. An obvious solution would be to divert part of the resources that fatten the private subcontractors who run US prisons to job creation and social services for low-income Latino and African Americans — two groups at high risk of incarceration. So why hasn’t that been done? Hinton argues that such an approach was tried, albeit halfheartedly, during the Kennedy and the Johnson administrations, but failed — not because it was inherently faulty, but in part because of the racist biases, overt or otherwise, of the people charged with implementing it.

Those racist biases may be in remission today, but they resurface reliably and with disheartening frequency. Among the shootings this summer was the police shooting of a 32-year-old black man, Philando Castile, during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. Because of a video posted to Facebook by Castile’s girlfriend, we know he was shot while reaching for his driver’s license and registration. He tried to tell the officer he was carrying a gun with a legal permit, which the officer may have misinterpreted. That fatal misinterpretation goes to the root of the fear in the United States about what the embittered black male might do. It turns out that Castile, a school district cafeteria employee (recently turned supervisor), didn’t quite fit the stereotype of the embittered black male. His girlfriend was a housekeeper at a hotel. As has been shown again and again, economically disadvantaged blacks are most commonly on the receiving end of police brutality. Castile had been pulled over so many times in the past for minor infractions (49 times in 13 years, according to The New York Times) that it sadly may not be so surprising that he got shot in the end.

President Obama has called police shootings “an American issue.” Tragically, the day after Castile’s shooting, a sniper — a black man — killed five police officers in Dallas, in an apparent act of retaliation. This is a moment in race relations when anxiety rules, when the police understandably feel as frustrated and cornered as their supposed victims, and when many well-meaning Americans fear what the next headline might bring.

¤

In her book, Hinton relates another moment, several decades back, when race-related anxiety had similarly peaked in the country. The Watts riots erupted during Lyndon Johnson’s administration in 1965, sparked by a drunk driving arrest and rumors that the police had kicked a pregnant woman. It is telling that the riots occurred in an economically depressed neighborhood of Los Angeles — the city was then in the grips of residential segregation. Watts’s residents were frustrated with record unemployment levels — “in Watts, as many as one in three people could not find work” — and the apathy of the officials whose job it was to care. Authorities responded by swarming the area with LAPD and National Guardsmen and enforcing a tight curfew in a zone “larger than the island of Manhattan.” Those who disobeyed the curfew were arrested or paid with their lives. Hinton writes that law enforcement authorities put up one sign at the boundaries of South Central Los Angeles that read: “Turn Left or Get Shot.” It is a chilling message, and one that black men continue to get today from the police, albeit in a more muted form.

I began to attend the University of Southern California a few years after yet another set of comparable riots in the city — the 1992 Rodney King riots — and the shadow of that event still lurked. USC has various community outreach efforts and its historic commitment to staying in South Los Angeles is commendable. Still, I experienced the university as an island of learning and privilege in an economically depressed sea. Living just two blocks from campus, in campus housing, I couldn’t help noting the disparity between the lives of the neighborhood residents and the USC population. It may seem like a superfluous detail to mention that the local supermarket carried almost no vegetables, but that was just one more tacit nod to the stereotype that black folk eat fried chicken, and, maybe, waffles. Various strip malls near the university had been destroyed during the riots, and rumor had it that no decent supermarket would set up shop in the area thereafter.

As I noted in my review earlier this year, Michelle Alexander addressed the hidden racism against blacks since slavery in her book The New Jim Crow, and more specifically how incarceration has been used against them in a systemic way. Hinton acknowledges the “groundbreaking” nature of Alexander’s book, but suggests we have to dig deeper to understand the true nature of the War on Crime. She argues that the country’s incarceration plague began not with Reagan’s War on Drugs, but that its roots go all the way back to a surprising source: Lyndon Johnson’s social welfare program during the Civil Rights era.

Some of Johnson’s signature “War on Poverty” initiatives, such as Head Start and Job Corps grew out of the Kennedy administration’s “early childhood education and manpower development programs.” The Kennedy administration began its delinquency prevention program as a forward-thinking measure, and Hinton explains that it was backed by academic research and included social scientists in policy discussions.

Whereas the Kennedy administration launched these social welfare measures as crime control initiatives, Johnson presented his administration’s attempt to suppress the “social dynamite” in African American urban neighborhoods as a larger, more expansive fight against poverty.

Both administrations had good, hands-on ideas, from pre-K programs to vocational job training. So what went wrong?

For one, the commissions and people charged with empowering disadvantaged blacks were unable to get past their racist biases. The programs were not decentralized or entrusted to, say, local black organizations — not even those with stellar records of service. In addition, programs that address the roots of complex social problems need commitment and time to yield results, but the unfortunate circumstances of urban violence such as the Watts riots turned the public mood. After Americans saw images of the riots — including of Watts residents damaging businesses owned by absentee whites — public opinion soured. Johnson responded by taking a tougher stance against crime and changing his focus from the War on Poverty to the War on Crime.

Putting more and better-equipped law enforcement officers on the street is a visibly shiny route to public safety and it is no wonder politicians so often turn to this Band-Aid solution. Under Johnson, resources meant for social services were diverted to law enforcement and the trend intensified so much under Nixon that soon social services were given little more than lip service. Despite some good intentions during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, impoverished blacks never got the sustained infrastructural support needed to transcend their ghetto handicap, and, instead, continued to experience racial prejudice, an opportunity deficit, and chronic unemployment.

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime doesn’t have the strong voice that makes The New Jim Crow such compelling reading, but, nonetheless, it is rich with details and synthesis that give the reader fresh insights into how the well-meaning policies of the Kennedy and Johnson eras went awry. Hinton quotes Johnson as telling state law enforcement planners in 1966: “If we wish to rid this country of crime, if we wish to stop hacking at its branches only, we must cut its roots and drain its swampy breeding ground, the slum.” It is interesting to ponder Johnson’s statement in light of what we know today. Greater police monitoring of black neighborhoods has resulted in stamping large numbers of black youths with criminal records, effectively shutting them out from robust participation in the economy and in society.

¤

Hinton details a 1967 cabinet meeting in which sniping was perceived as “a new and deadly development.” It was acknowledged that the police responded to sniping by firing randomly and risking hundreds of civilian casualties and worse: “the danger of a riot degenerating into a guerrilla war.” It turns out that the numbers of sniping incidents were inflated, but what was clear was that sniping targeted “symbols of police power.” In the summer of 2016, sniping was used in a similar context — as a way to wage war against the police for perceived grievances. This is a troubling development, not the least because it distracts from the job of addressing hidden racism in the country.

Because of retaliatory incidents — such as the shootings of the five policemen in Dallas — the Black Lives Matter movement risks losing some gains it has made in public empathy and in what could have become a national resolve to end racial profiling. Many a movement has fizzled, or a positive outcome has been delayed, when unexpected violence turns the tide of public opinion. In the ’60s, National Guardsmen were called in to suppress unrest in areas such as Detroit, Chicago, and Watts. Hinton quotes one guardsman in Detroit as saying, “If we see anyone move, we shoot and ask questions later.” Today, our officers have to challenge themselves to shun the racist, murderous attitudes of the past, while, of course, keeping their own safety in mind. It is true that police officers are being scrutinized more for actions that may be racially biased, but we are also finding out in many instances that after the brouhaha has died down, the officers in question are not actually being charged for their brutality.

Dallas’s police chief David O. Brown — a black man — has suggested after the recent shootings, that the police force is asked to take on too much:

Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding, let the cop handle it. Not enough drug addiction funding, let’s give it to the cops. Here in Dallas we got a loose dog problem. Let’s have the cops chase loose dogs. Schools fail, give it to the cops. Seventy percent of the African-American community is being raised by single women. Let’s give it to the cops to solve that as well.

It would be interesting to find out what kind of money Congress allocates today for, say, social services or job training, how much actually trickles down to those programs, and how those funds could be increased. A segment of the population reliably howls murder whenever a significant investment is made to social services. But no one protests when law enforcement acquires fancier helicopters. Our police officers obviously need to be equipped in the best way possible, but when the allocation of resources has historically been so skewed in favor of law enforcement that the man in the ghetto sees almost nothing, or at least not enough to help him overcome the handicaps of ghetto living, that also hurts police officers. In her book’s introduction, Hinton writes, “states like California and Michigan spend more money on imprisoning young people than on educating them.”

¤

In 1968, the Kerner Commission warned that “[i]n the absence of a major commitment of resources on the part of American political and economic institutions, ‘sufficient to make a dramatic, visible impact on life in the urban ghetto,’ […] the nation would be plagued by crime, violence, and lasting inequality.” Though Johnson had commissioned this report, he looked the other way. It goes without saying that Nixon also looked the other way. Instead, in the early ’70s, the Nixon White House launched the ill-conceived High Impact program to reduce crime in eight cities with serious crime problems.

While reading Hinton’s book, a reader might question: Why did supposedly targeted programs such as $160 million High Impact program fail so abysmally? For one, the Nixon-era War on Crime had corruption oozing out of its ears. The headquarters of LEAA (Law Enforcement Assistance Administration), the federal government’s law enforcement consultant, got a luxurious remodel, replete with an office with “modernist silver foil walls and a private bathroom” for its director, Jerris Leonard, a former member of “three all-white social clubs in Milwaukee.” Funds dispersed to a state might inexplicably be siphoned off toward, say, a plane for a governor. Overall, significantly more money was spent on more policemen and more gizmos (helicopters, TV monitors, etc.) than on support services for young black men and women. An independent evaluation by the National Security Center chastised the High Impact program as being an “irresponsible, ill-conceived and politically motivated effort to throw money at a social program.”

Surprisingly, there have been no fundamental shifts in government policy to alleviate inner city problems, despite the documented failure of efforts such as targeted surveillance and heavy policing in impoverished black communities. Instead more prisons have been opened to shut in the ghetto’s problem children. In Nixon’s time, the boom in prison construction was based partly on what turned out to be incorrect census projections that young black men would become the fastest growing demographic in the country:

At a time when a number of policymakers, criminal justice authorities, and public figures were calling for the termination of prisons amid a growing prisoners’ rights movement, emphasizing instead community-based alternatives, the Nixon administration’s drive to increase the nation’s penal population seemed all the more regressive. “I am persuaded that the institutions of prison probably must end,” U.S. district court judge James Doyle reflected in a 1972 ruling in Wisconsin. “In many respects it is intolerable within the United States as was the institution of slavery, equally brutalizing to all involved, equally toxic to the social system, equally subversive of the brotherhood of men, even more costly by some standards and probably less rational.”

More recently, at the Democratic National Convention, Hillary Clinton said that our incarceration system needs an overhaul. Whether that is lip service to voters or whether, if she is elected president, she will put political will behind closing prisons, only time will tell. Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, on the other hand, expressed his support for private prisons to political commentator Chris Matthews. Trump’s assessment is that private prisons “work a lot better.” Among his considerable base, Trump has stoked white racial identity — and the deportation of Muslims — without addressing realities on the ground, much less realities in the ghetto. American demographics are undeniably changing, and it is inevitable that the country already looks different. In this time of uncertainty, change, and adjustment, a graceful solution might be to think in terms of a post-racial society: a meritocracy that acknowledges our different cultures while fostering shared values. While Trump enjoys a bucket of fried chicken in his private plane (The New York Times), he would do well to consider how his privatization-works-just-fine approach to prison reform will move the country away from the dark legacy of the Nixon-era prison boom or reduce our annual $80 billion prison bill.

¤

LARB Contributor

Priyanka Kumar is the author of the widely acclaimed book Conversations with Birds (2022). Her essays and criticism have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Orion, and The Rumpus.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Are We Done Punishing Black Men?

After Michelle Alexander’s measured assessment of mass incarceration in "The New Jim Crow," it is no longer possible to look the other way.

Murder, They Wrote

How can you get your head around 297 homicides in Los Angeles in 2011, with pitifully low clearance rates for black-on-black murders?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!