Tripping Toward Stardom: The Life and Career of Dennis Hopper

Peter L. Winkler on "Along for the Ride" and the making of Dennis Hopper's "The Last Movie."

By Peter L. WinklerJanuary 26, 2018

DENNIS HOPPER’S roller-coaster life and career was characterized by incredible successes followed by equally incredible failures — none more so than The Last Movie (1971), Hopper’s ambitious directorial follow-up to the box-office smash Easy Rider (1969). That film’s unexpected success transformed Hopper from a Hollywood pariah into everyone’s hot ticket to the youth market.

Hopper is the subject of director Nick Ebeling’s new documentary, Along for the Ride (2017). Narrated by Satya de la Manitou, Hopper’s right-hand man for over 40 years, the film skillfully weaves together new interviews with 31 of Hopper’s friends and colleagues with well-chosen clips from Hopper’s films, archival footage, and still photos. Hopper was the proverbial overnight discovery: only six months after the fresh-faced kid had graduated from Helix High School in San Diego, he landed a contract with Warner Bros., where he acted alongside James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Giant (1956). Those were heady days for the 19-year-old Hopper, who received informal acting advice from Dean, with whom he claimed to have smoked pot and taken peyote. Hopper idolized Dean and began emulating his personal style. “[Dean] was also a guerilla artist who attacked all restrictions on his sensibility,” he later recalled. “Once he pulled a switchblade and threatened to murder his director. I imitated his style in art and in life. It got me into a lot of trouble.”

Hopper’s troubles began when he locked horns with bellicose director Henry Hathaway on the set of the Western From Hell to Texas (1958). They fought constantly over Hopper’s interpretation of his role, until the last day of filming, when Hathaway finally broke his will after shooting dozens of takes of the same scene. With his cigar in his mouth, Hathaway promised the tear-stained Hopper he’d never work in the town again. Hopper later adorned a closet door in his house with a copy of the film’s poster.

Hopper then worked sporadically in episodic television and two films (including director Curtis Harrington’s cult favorite, Night Tide [1961]), until Hathaway gave him a reprieve, casting him in The Sons of Katie Elder (1965), starring John Wayne and Dean Martin. Wayne and Hathaway took pity on Hopper. “Well, his reason for hiring me was because he and John Wayne, the Duke, heard that I’d married a nice Irish woman, Brooke Hayward,” he said. “They knew her mother, Margaret Sullavan, who was a nice Irish woman. I’d married her daughter, and we had a daughter of our own, so it was about time for me to go back to work. That was Hathaway’s way of putting it to me in the office.”

While on location in Durango, Mexico, for The Sons of Katie Elder, Hopper wondered about the impact of an American movie crew’s intrusion on the indigenous population. “I thought, my God, what’s going to happen when the movie leaves and the natives are left living in these Western sets?” Hopper’s observation became the inspiration for his passion project, The Last Movie, the film that he finally got to direct in 1970.

Hopper approached his friend Stewart Stern, the screenwriter of Rebel Without a Cause, to write a screenplay based on his idea. “According to Stern,” Esquire’s Robert Alan Aurthur wrote,

one day Dennis Hopper, “a really wonderful guy,” dropped by the house with an original idea for a picture and needed to see what a proper screenplay page looked like. The first result was a collaboration where Stern shaped a screenplay from Hopper’s idea; the final result, the picture, was a disaster.

No one in Hollywood was the least bit interested in The Last Movie or anything else Hopper had to offer. “I was looked on as a maniac and an idiot and a fool and a drunkard,” he later said. Hopper would get high at parties and end up confronting the aging gatekeepers to the studios to which he longed to have access. He’d jab his forefinger in their chests and tell them that heads would roll when he and his friends staged their palace coup. All that changed when Easy Rider, a little movie no one saw coming, was released on July 14, 1969. Made for about $500,000, it raked in nearly $20 million in its first year of release and made its stars, Peter Fonda and Hopper, the latest heroes of the American counterculture.

Enter Satya de la Manitou, director Nick Ebeling, and Along For the Ride — a significant portion of which is devoted to recounting the making and unmaking of The Last Movie, which both men offer as proof of Hopper’s enduring artistic genius. Ebeling’s life was transformed when he discovered a shopworn copy of The Last Movie on VHS when he was a teenager. He proceeded to devour whatever else of Hopper’s cinematic oeuvre he could get his hands on. Several years ago, he met de la Manitou, who fell into Hopper’s orbit in Taos, New Mexico, in 1970 and became his devoted personal assistant and sidekick. De la Manitou’s faith in Hopper’s genius was exceeded only by Hopper’s own. Astonished that Ebeling not only knew about The Last Movie, but loved it as much as he did, de la Manitou regaled him with stories about Hopper over coffee in a Hollywood diner; the product of their sessions became Along for the Ride.

After de la Manitou introduces himself in the documentary, explaining his past relationship to Hopper, a series of talking heads he interviews — former Universal Pictures executive Daniel Selznick, Hopper’s onetime agent Michael Gruskoff, and others directly involved in the production of The Last Movie — provide a synoptic version of the film’s creation and Universal’s eventual abandonment of it.

Universal gave Hopper a sweet deal to make The Last Movie: a million-dollar budget and creative carte blanche, including the much sought after privilege of final cut. So Hopper, his cast, crew, and his cronies flew down to Chinchero, a small village located high in the Peruvian Andes, where they proceeded to consume mountains of cocaine and engage in general debauchery while shooting the film. Far from the watchful eyes of Universal Pictures, Hopper strayed from Stewart Stern’s screenplay, choosing instead to improvise scenes as they came to him. “I loved the script. I’m sorry that in many ways, we didn’t shoot the script,” Paul Lewis, a Hopper loyalist who produced The Last Movie, now recalls.

Hopper decamped from Peru after wrapping his film, returning to Los Angeles with 48 hours of footage. He announced his engagement to Michelle Phillips and casually informed the suits at Universal that he was going to take a year to edit the film. He repaired to Taos and took up residence with a crew of editors in the adobe mansion he had purchased that once belonged to art maven Mabel Dodge Luhan, which he had outfitted with state-of-the-art editing equipment.

Hopper called the editing room a prison, so editing The Last Movie often took a back seat to Hopper’s foolishly hedonistic hijinks, some of which are on display in Along for the Ride via clips from The American Dreamer (1971), a cinéma vérité documentary directed by Lawrence Schiller and the late L. M. Kit Carson, who followed Hopper around in Los Angeles and Taos for 30 days while he edited his film.

Watch Hopper fire assault weapons in the desert! Watch Hopper cavort with a couple of girls in a bathtub! Watch Hopper stage a sensitivity encounter with a harem of Playboy Playmates Schiller and Carson imported from L.A.! Hopper finally emerged from Taos after spending 18 months editing The Last Movie, ready to take his brainchild public with a schedule full of promotional activities and future film projects.

Universal’s executives were horrified by The Last Movie. When Lew Wasserman, chairman of MCA, which merged with Universal, went to see the film, its nonlinear structure led him to suspect that the projectionist had put on the wrong reel. “Well,” he said, “it doesn’t really matter which reel they put on because this is a piece of shit.” Wasserman demanded that Hopper recut the film and have Kansas, the character he played, killed at the film’s climax. When Hopper refused, Universal gave the film a desultory release and shelved it. It played at a few drive-ins under the title Chinchero (1971) before disappearing into the elephant’s graveyard of late-night TV. “I had final cut,” Hopper later said, “and cut my own throat.”

The critics were no kinder to Hopper than Universal had been. Crushed by the failure of The Last Movie, Hopper retreated to Taos, where he exiled himself for nearly the next 15 years, working sporadically on films made outside the United States, like Mad Dog Morgan (1976), Apocalypse Now (1979), and Out of the Blue (1980), the last of which he also directed. His alcoholism and cocaine binges reached epic proportions, until he finally suffered a psychotic break on location in Mexico. He eventually embraced sobriety and worked prolifically after Blue Velvet (1986) revived his career.

¤

Swiftly paced, the often engrossing Along for the Ride loses steam in its final 20 minutes, which touch on Hopper’s last 24 years after Blue Velvet, the least interesting part of his life. Hopper suffered a paucity of good roles; stuck on the treadmill of mediocrity, he played seemingly endless variations of Frank Booth in crappy, forgettable films. Hopper’s reputation became that of a surviving counterculture icon who invested most of his creative energy into curating his own legacy and collecting branded avant-garde art.

Ebeling squanders precious screen time here, interviewing people who had some connection to Hopper but have little of interest to contribute: a makeup artist who worked on Hopper for Wim Wenders’s Palermo Shooting (2008) (still unreleased here seven years after Hopper’s death); Hopper’s gallerist Tony Shafrazi, who began representing his photos and paintings after Blue Velvet revived his celebrity; and artist Julian Schnabel. Frank Gehry seems to be in the picture only to confirm Hopper’s artistic brilliance: one genius salutes another.

When Ebeling puts someone on screen who has something to say, he cuts away from them too quickly, and de la Manitou, who is not an experienced interviewer, fails to pursue certain obvious lines of questioning. Todd Colombo, who helped edit The Last Movie, recalls Hopper’s undisciplined editing regimen, but is not asked how Hopper arrived at his controversial creative decision to present the film’s story in a nonlinear fashion.

The person I wanted to hear more from was de la Manitou. Where are the stories he told Ebeling over coffee, which compelled the director to make Along for the Ride? Instead of tapping fully into de la Manitou’s store of personal memories of Hopper, Ebeling seems content merely to use him as a clever conceptual device to tie together the interviews in Along for the Ride. A couple of anecdotes de la Manitou relates provide glimpses into Hopper’s considerable dark side, the kind of insight into his personal life the film needed more of. In one scene, de la Manitou recalls how he managed to wrangle a reluctant Hopper into rehab. Later that night, he received a frantic call from someone at the facility begging him to come down immediately to deal with Hopper, who was apparently speaking in tongues while moving his hands against a wall in his room. When de la Manitou arrived, he discovered that Hopper had been calling out his first name repeatedly, convinced that the men in white suits had plastered Satya inside the wall. De la Manitou gently touched Hopper on his shoulder and told him, “Dennis, it’s okay, I’m here.” The ineffable sadness of this story makes it the most touching in the film.

While not the definitive account of Hopper’s life, Along for the Ride will reward viewers seeking an entertaining introduction to its subject. It goes down smoothly, thanks in no small part to Hopper’s charisma and energy that shine through the film, and remains worth seeing for its affectionate portrait of this “live wire who lived on the high wire,” as director Philippe Mora once so perfectly described him to me.

¤

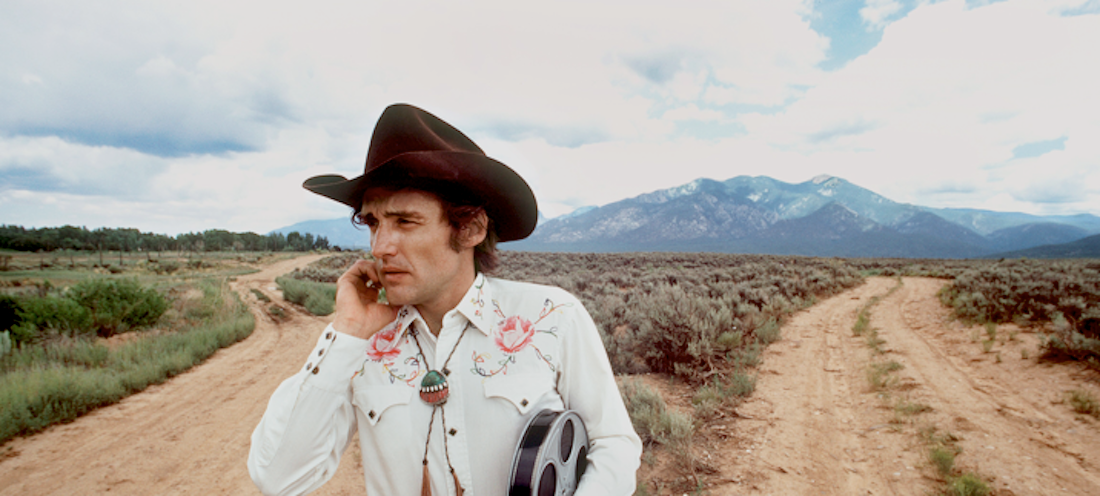

Image: Dennis Hopper standing in front of the Sacred Mountain in Taos, NM, circa 1971 © Douglas Kirkland

¤

LARB Contributor

Peter L. Winkler is the author of Dennis Hopper: The Wild Ride of a Hollywood Rebel (Barricade Books, 2011) and the editor of The Real James Dean: Intimate Memories from Those Who Knew Him Best (Chicago Review Press, 2016).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Burt Shonberg and Bohemian Los Angeles: An Interview with Spencer Kansa

John Wisniewski interviews Spencer Kansa about his latest biography, “Out There: The Transcendent Life and Art of Burt Shonberg.”

Negotiating the Dangerous Compromise: Curtis Harrington’s “Nice Guys Don’t Work in Hollywood”

"The thrust of the film,"Harrington says, "is to present the artist as an alchemist who, through her creative work, becomes herself transmuted into...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!