Tom Hayden According to the Enemy

M. Delmonico Connolly considers the FBI file on 1960s icon Thomas Hayden.

By M. Delmonico ConnollyJune 14, 2022

THE FIRST NOTICE the FBI took of Thomas Emmet Hayden was an article he wrote for his college newspaper in 1960: “Student ‘Dupes,’ Adult ‘Patriots’ and the Communist Menace.”

If we are all either dupes or patriots in the eyes of the FBI, then Hayden would become one of its biggest dupes: a student rebel who drafted the Port Huron Statement, learned activism at the feet of the Southern Civil Rights movement, worked with the poor in Newark, and traveled to any place in the world or the country that could have menaced the US government.

His indictment and the consequent trial for conspiracy to incite a riot following the Democratic Convention in Chicago 1968 made Hayden — “Mr. Underground” according to the caustic critic Elizabeth Hardwick — a household figure, along with fellow defendants like Black Panther Bobby Seale and Yippies Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, but the FBI knew of him long before. By 1979, Hayden had settled in Los Angeles, a city that would become the seat of his political activity for much of the rest of his life. His file had blossomed from that first clipped student newspaper column to 22,000 pages of surveillance and research, the first 600 of which are now available to the public.

To read through Hayden’s file is to witness the FBI as a massive system for storing and retrieving information loaded with its own sense of domestic threat. The file collects every scrap of paper that the agency had written on Hayden and his known affiliations. Through countless memoranda, records slips, and typewritten reports, a version of the activist emerges. With its pretense of objectivity, the FBI commits no definitive conclusions to paper, but the picture is clear: the FBI’s Hayden is one that “out-radicals the radicals,” with communist ties and an interest in racial matters.

Between the redacted lines and chatter from anonymous student movement informants, one sees a government chasing a shadow that menaced it. In retrospect, it is easy to dismiss the FBI’s fear of the student movement as naïve; one can’t quite imagine those midcentury teens as the tip of the spear, especially seeing them now. But the FBI’s Hayden is also driven by conviction and sincerity to take actions so bold that it can’t seem to anticipate them. As Hayden evolves from a student rebel to an activist in an interracial movement of people living in poverty to someone conversing with guerrilla fighters in Vietnam and Cuba, something interesting begins to happen in the FBI’s portrait. On the other side of all that fear and paranoia is an ordinary Midwestern white American learning how to change his country.

Born in 1939, Hayden grew up in Royal Oak, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit whose population nearly doubled between 1940 and 1950 and again in the following decade. Royal Oak was one American response to postwar affluence: with restrictive covenants and federal housing policies, its white inhabitants kept it white, and so it largely remains.

A “Betty Adams” tells the FBI that Hayden attended Dondero High School. A counselor informs that he was the editor of the student newspaper, “very intelligent” but “refused to recognize authority and accept discipline.” Under a “suitable pretext,” agents contacted Hayden’s mother, who reveals her son is “completely different from herself and other members of her family” –– that is, he is very idealistic.

Hayden floated in “a material paradise with all things provided, all choices made, everything laid out neatly,” he writes in his memoir Reunion. “A fine, normal upbringing in America had left me anticipating a lifetime of unfulfilled expectations.” Collegiate life at the mass bureaucracy of the University of Michigan was likewise depersonalizing in the best ’50s tradition — until he began working for the student newspaper.

Hayden married reportage to Beat romanticism, hitchhiking across the country from the Latin Quarter of New Orleans to New York’s Greenwich Village, writing stories along the way. In journalism, Hayden found a career that satisfied his longing for vitality with professional ambition. He was called, and in other circumstances, that might have been enough to quiet any spiritual anxieties about a life of comfort. Then on February 1, 1960, four Black students entered a Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, sat at the segregated lunch counter, and ordered a cup of coffee and a donut each. When an Ann Arbor store was boycotted for discrimination the next month, Hayden covered it for the paper, and two weeks later the deep unease beneath white utopia surfaced under the heading “This Land is Your Land…” Hayden’s style was cool but pointed as he documented a litany of racial abuses: “In Houston, Felton Turner, a 27-year-old Negro, is taken to a quiet glade where four men beat him with chains, then slice ‘KKK’ into his chest and stomach.”

That summer, Hayden hitchhiked to Berkeley, where he met members of SLATE, a student political party demanding governance of the UC campus. He attended a disarmament rally and memorial for the US bombings of Japan. Activists took him to Delano, where he witnessed efforts to unionize Chicano farmworkers. Everything was already happening here.

He went on to the Democratic Convention in Los Angeles, where activists picketed for a stronger civil rights plank. Hayden interviewed Martin Luther King Jr., later recalling King’s gentle words to him: “Ultimately, you have to take a stand with your life.” He felt uneasy taking down the quote like a reporter. “I asked myself why I should be only observing and chronicling this movement instead of participating in it.”

But he didn’t make up his mind until the National Student Association (NSA) conference at the University of Minnesota. In the years to come, it was discovered that the CIA funded the NSA, part of a Cold War mission to funnel political protest toward safe institutions and give the impression that the United States was advancing freedom abroad and at home. Still, the NSA was a meeting place for freshly politicized students, and not even CIA plants could contain them completely. That year, 25 members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) attended. Hayden was impressed by their intellect and electrified by their commitments: “They lived on a fuller level of feeling than any people I’d ever seen, partly because they were making modern history in a very personal way, and partly because by risking death they came to know the value of living each moment to the fullest.”

He was particularly struck by Sandra Cason, who entered the movement at the University of Texas, Austin. Already involved with the YWCA, Cason attended a talk by the national president, a Black woman, who described her experience in a march, broken up by police tear gas, where she was arrested and jailed. Cason cried listening to her in a packed auditorium. She joined an intentional living community and began reading Thoreau and Camus. “My clearest memory of this spring of 1960,” she writes, “is picketing on Congress Avenue in a yellow dress and high-heeled white pumps.”

At the NSA, an all-white panel responded to the SNCC presentation, and Cason was tapped for rebuttal. The three other panelists spoke about the legal right to discriminate. Against that moral grayness, Cason was a thunderbolt. Straight from the South, where students packed jails in stunning acts of courage, she called up the exchange between Thoreau and Emerson: “When Thoreau was jailed for refusing to pay taxes to a government which supported slavery, Emerson went to visit him. ‘Henry David,’ said Emerson, ‘what are you doing in there?’ Thoreau looked at him and replied, ‘Ralph Waldo, what are you doing out there?’” Five hundred students rose in applause.

“I fell under Casey’s spell at once,” Hayden recalled. They met only briefly, but he idolized her. Cason too returned home “aflame.” She met with her university’s president on housing integration, coordinated meetings with campus groups on direct action, and met with the University Religious Council to encourage restaurant integration. Cason described the pull of “romance within action, or perhaps action within romance.” And like her, Hayden’s “most serious longings […] were pointed south to the civil rights movement” and to Casey. They would soon marry.

Moving from chronicler to participant, Hayden caught the attention of the FBI. In 1960, the Bureau began to expand its operations under a suite of activities that amounted to the Counterintelligence Program, or COINTELPRO. Over time, these would include surveillance, disinformation, infiltration, and assassinations. But in 1960, Hayden merely had to defend students against the charge of being communist dupes: “Hoover and other Americans might find, instead of subversive dupes, young men and women fed up with repressive police, legislative and judicial tactics cloaked by the banner of Anti-Communism.” That was all it took. The editorial spurred the Detroit FBI office to call up all files on Hayden.

A thin portfolio then, the earliest reference to Hayden is from an informant who calls him a “responsible, aggressive, student leader whom he regards as completely loyal to the United States,” vouching that his “activities were based on sincere personal conviction” and that he was never a member of any communist-sponsored or sympathetic organizations.

The FBI seemed to take the source’s word, for it took no notice when Hayden traveled to Mississippi to cover SNCC’s voter registration efforts in Amite County, where they faced a campaign of intimidation that began with police beatings and ended with a state representative murdering a participant. In these days of “nonviolence,” Hayden and fellow activist Paul Potter had to sneak into the county, moving secretly by car, staying in hotels and cellars with shutters drawn. To discuss the most conventional political activity was to embark on conspiracy. For the obvious outsiders, even white skin offered little shelter. Followed constantly as they sought to cover SNCC’s activities, Hayden and Potter were eventually pulled from their car and beaten.

Nor was the FBI interested in what was arguably Hayden’s most famous act. Since the fall of 1960, he and another Michigan alumnus, Al Haber, had begun working as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The organization envisioned itself as the Northern counterpart to SNCC. Even more than its causes, it was inspired by the existential bravery with which SNCC faced down death and imprisonment. In 1962, at a convention in Port Huron, Michigan, SDS began to define itself. Hayden stitched together their various commitments and principles to draft their “statement.” Addressing both continuity with the Old Left and establishing SDS as a new force, Hayden outlined the moment: “We are people of this generation, in our late teens and early- or mid-twenties, bred in affluence, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.” While every generation inherits the problems of the past, theirs was the first in the United States to grow up knowing that, with nuclear annihilation a looming threat, they could be the last. Committees workshopped the statement, somehow charting their way around sedimented Marxism and liberalism, instead “speaking American,” as one reader had it. They discovered their values in the new terms: “We regard men as infinitely precious and possessed of unfulfilled capacities for reason, freedom, and love.”

Hayden’s name resurfaced for the FBI in Newark, New Jersey, as they investigated “Communist Influence in Racial Matters.” As the student group grew, it debated what it should do. Potter, president of SDS in the mid-’60s, wanted to see the organization dig into its natural constituency — college-educated whites — but there was strong resistance to the idea. Potter reflects, “I think people felt the middle class would never make it, that our sector of the society was not going to produce a revolution, and that we had to split with it.” The dilemmas of moral culpability for the oppression of Black people and the Vietnamese, of spiritual alienation in a technological world — these were not legitimate problems, and only those with true grievances would rebel, or so the thinking went. But Hayden wanted to prove that the young white radicals were real allies.

Whatever their lofty goals, the issue on the ground for the Newark Community Union Project (NCUP), in the predominantly Black Clinton Hill, was traffic. Hayden remembered, “I used to think such issues were ‘superficial,’ they didn’t deal with root problems, etc. […] I had to learn that real children are killed, all the time.” With lessons learned from SNCC, teams canvassed the neighborhood, listening to complaints and pitching a community group. Maybe one in 10 or 15 would respond positively, but out of 150 houses enough could be found for a meeting. At the meetings, one person after another would speak on the issues they were dealing with, “until they were all shaking their heads in agreement and a system of collective abuse had become apparent.”

Then in late 1965, an SDS informant told the FBI that Hayden had departed the United States for Hanoi, North Vietnam, in the company of professor Staughton Lynd and communist Herbert Aptheker. The FBI interviewed his mother under false pretenses and uncovered his arrest record. They traced his movements leading up to the trip and interviewed passport officers, embarkation officials, and flight crews. Dossiers on Lynd and Aptheker were also entered. The web of associations spread. When the three returned from Hanoi, every article mentioning the trip was clipped and Xeroxed, every speech reported, their activities logged. Though not yet the subject of daily surveillance, Hayden’s stature was sufficient that in the spring of 1966 he entered the FBI’s “Security Index.”

In Hanoi, Hayden was inspired by guerrilla fighters’ directness and openness. He found a people discovering themselves in a revolutionary process. The trip expanded his curiosity beyond the continental United States, spurring travel to Puerto Rico to learn about the national independence movement and to Cuba to see what the socialists had made. His public speech became inflected by an interest in guerrilla struggle, dotted with praise for Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong, and Che Guevara. He was quoted declaring, “A Negro stoning a brutal police officer in Watts, Newark, or Cincinnati is an encouraging sign.” But Hayden was also racing to find traction as the Civil Rights movement flagged, as Black Power exerted its charisma, as the rancor of the antiwar movement escalated. The FBI noted that he spoke about “empire” and “revolution” now: “Unless the affluent people of the United States can be moved to action, the US will take the rest of the world with it. […] We must do something ‘so shocking’ as to move the people.”

In 1967, Newark rioted. Police violently beat a Black cabbie over a minor traffic violation. They dragged him into the station and continued to beat him. Word spread, and the uprising ensued. Despite four years’ worth of contacts with Newark’s civil rights organizations, Hayden and NCUP could find no purchase on the unfolding events. The front lines were made up of mostly young men from the city’s projects. They weren’t members of any organizations, but “unorganized,” they coordinated a citywide response to the police’s brutality.

Against typical characterizations, Hayden defended the uprising. “To the people involved, the riot is far less lawless and far more representative than the system of arbitrary rules and prescribed channels which they confront every day.” And why not? But the organizer must have been chagrined as well. More wealth was redistributed in one weekend than in years of painstaking work. NCUP could not even force the city to install a traffic light. When the governor summoned the National Guard from the surrounding suburbs, they killed five residents in the first few hours. By the time the riots ended, 26 had died, some killed outright by police and troopers, some by their careless bullets fired into houses and apartment complexes, one struck by a military vehicle, and one, a heart attack, by fear.

What could be said about the FBI is that they leveraged tremendous resources to monitor the activities of an organization that failed to get a traffic light installed in a poor part of Newark. But that is a simple way to make them look ridiculous — for SDS’s real failure was not a traffic light, but that for all their effort, they could plot no strategy for the people of Newark more hopeful than a riot. And complicit in that large failure, whether they claim it or not, are a city council, a mayor, a governor with his National Guard, all feckless, and an FBI too inured to anything as mundane as a traffic light to stop chasing communists.

In January 1968, a customs agent at the Port of New Orleans confiscated a letter that Hayden had written to fellow activist Rennie Davis. The letter called for a massive demonstration to clog the streets of Chicago during the Democratic Convention to expose “the mockery that democracy has become.”

One wonders if there was a Hayden expert at the FBI, a records clerk who had seen the whole story from the first scrap to the last anxious confiscation. If so, what would they have felt? Growing fear as Hayden radicalized or vindication as a communist showed his true colors? Or would they have pitied Hayden, as they watched his decade-long search for a lever that might move the country from its violence, its need for domination, its sense of superiority? More likely, there would have been an endless series of such clerks, anonymously cycling through the hundreds of thousands of Haydens that the FBI kept tabs on, glimpsing only a snatch of paper at a time.

¤

¤

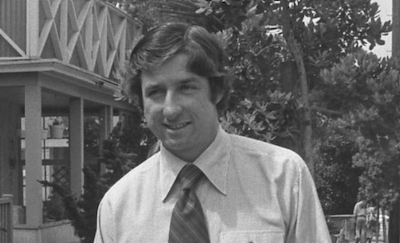

Featured image: "Tom Hayden with his wife, Jane Fonda and their son, Troy walking in Santa Monica, Calif., 1976" by William S. Murphy and UCLA is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Image has been cropped.

LARB Contributor

M. Delmonico Connolly is the author of Ronnie Spector in Rock Gomorrah (Gold Line Press, 2020) and an editor at the Albright-Knox Art Museum in Buffalo, New York. His research explores the crossroads of journalism and leftist organizing, and his writing on pop music, comics, and the subliterary — usually through the lens of race — can be found on Full Stop, SOLRAD, and The Comics Journal.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Show Trial Gets Its Show

A film about the marquee trial of the 1960s counterculture fails to explain its enduring relevance.

The Great Distraction: On Aaron Sorkin’s “Trial of the Chicago 7”

J. Hoberman passes judgment on “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” directed by Aaron Sorkin.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!