To Read a Carpet: An Interview with Reimena Yee

Reimena Yee talks with M. L. Kejera about the intersection of carpets and comics in “The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya: Volume II.”

By M. L. KejeraOctober 8, 2022

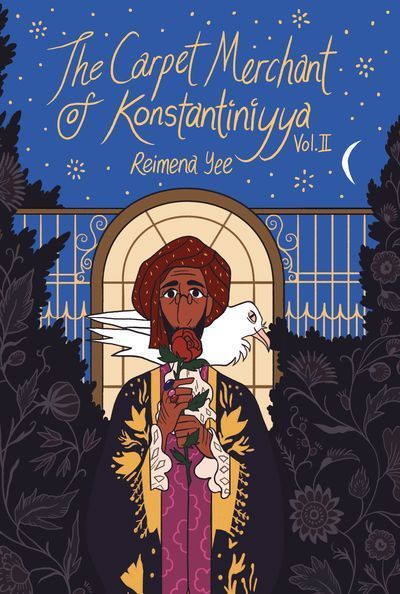

The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya: Volume II by Reimena Yee. Unbound. 336 pages.

REIMENA YEE, illustrator and Eisner-nominated author of The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya (Volume II was released in August 2022), talks with M. L. Kejera, a Gambian author and comics journalist who has covered her work for years.

¤

M. L. KEJERA: What struck me when first reading The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya was the connection you make between sequential art and the tradition of carpets. In Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud posits medieval tapestries, which are related to carpets, as precursors to modern comics. Our protagonist, the timid vampire Zeynel, refers to carpets as “essentially moving stories.” The process of reading a comic and admiring a carpet are similar in that the reader works to connect the images in some sort of visual order. Could you elaborate on your sense of the relationship between carpets and comics?

REIMENA YEE: As objects, carpets and comics are both physical manifestations of their creator: they reflect a creator’s sociopolitical, cultural, or religious context; their access to power; aspects of their lives like geography, ancestral history, and access to materials; as well as who they were and where they lived at the time of the work’s creation.

To read a comic or a carpet is to glimpse at the individual, specific, microcosmic slice of humanity responsible for its creation. Learning to read the visual language of carpets or comics means unlocking even more of that humanity, moving beyond the superficial and passive “Oh, this art is pretty, and I like this story!” to the formation of a deeper, active connection with the artist who made that work. Thematically and narratively, TCMK posits that the work of understanding the carpet is analogous to understanding a person: all of us are moving stories, each with something to say to those who want to learn. The reader who goes even further to apply this thesis to TCMK itself will find traces of its creator: who I was and some of who I am now are essential to its becoming.

I wouldn’t directly draw a line between carpets and comics — they are very different mediums. Carpets are more akin to illustration: they are static, containing multiple components that express an idea or concept, and they stand alone. Outside the concerns of interior design, a carpet doesn’t need another to support its own aesthetic or personality. In a strictly visual sense, I only make that connection between carpets and comics because Turkish miniature very much owes its decorative flourishes (borders, florals, arabesques) to carpets.

The other major visual inspiration for The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya is, of course, Turkish miniature. The link to comics is stronger there, I imagine. Do you view miniature as part of the tradition of comics?

The miniature (Eastern and Western) occupies the same space as tapestry and comics in that they are all part of the tradition of visual storytelling. However, unlike tapestry, I think miniature has a stronger connection to comics because both are tied to the combined histories of the book arts, printing, and literacy.

Your dedication to thorough historical research, going so far as to consult a historian for your current webcomic Alexander, the Servant & the Water of Life, is one of my favorite things about your work. You cite sources and suggest other works curious readers might follow up on. The inclusion of the large number of visual references ameliorates the reading experience. Why is research so important to you? What does your research process look like? At what point do you stop researching and get to work?

I think research is important because I don’t know everything. Write what you know, goes the advice. So if I want to write about more things, then I must know more. Doing research and engaging in critical analysis of one’s own media diet and biases are essential to storytelling craft, especially if the goal is to present something thoughtful. Or at least, not unconsciously, carelessly perpetuating bad information. But it’s not for those reasons why I primarily research. I do so because I have always been someone who reads voraciously and had once wanted to pursue academia. I love learning.

I have written about my research process in my blog and websites.

How do you view yourself in the tradition of comics? Who are your antecedents? What do you hope to inspire, if anything?

I do comics because this is where I am most eloquent, but I don’t limit myself to just comics. I see myself as one drop in an ocean of artists: musicians, illustrators, writers, people who make art as part of the human experience. I only have one life purpose, and that’s to share my joy for the world, its history, and our collective heritage. All of my comics have this as their driving force.

As someone who is part of the larger human tradition of creativity, who — as you so brilliantly put it — is “most eloquent” in sequentialization, what do you think this form does that others cannot, or cannot do as well? What does it struggle to do but you still find worth in pursuing?

Sequential art is not very good at capturing emotionality in sound. I always loved the moment in movies when characters fall apart and their voice cracks — it’s so beautifully vulnerable and meaningful. In comics, it’s so awkward. But I can live without that, since sequentialization gives me the ability to have multiple POVs, time periods, and conflicting information share the same instance of space-time — which is something film and prose cannot do.

You’ve written guides to aid both comics creators and journalists to move away from the filmic language used to discuss comics, as is currently prevalent in the industry, to comics-specific language. I think most people reading comics scripts for the first time might be shocked to find the word camera present so frequently. Why is comics-specific language important to you? How, if at all, has this changed the work you produce or your process?

Comics being seen as a lesser medium to prose, or a stepping stone to something more prestigious like film, is an unfortunately common attitude, and I think that is due to the way we comics creators speak about our work. We always try to frame, compare, or justify comics using the language of another medium that the public finds more acceptable (i.e., less embarrassing), usually film. This is very odd to me, because film and comics are sibling mediums: they were born around the same era and therefore had the same amount of time to develop their own language. In the history of comics, few comics creators put words into their process, or pursue an academic path to develop theories and name “objects” or offer perspective — that is, if they survive long enough to stay in comics. And so this lack of material, of ways to talk about comics as a medium by itself, forces creators and journalists to borrow the language from more rigorous and well-funded industries, which has the unintended side effect of positioning comics as “lesser than.”

I’m currently working on a Carl Linnaeus–esque project, identifying and naming visual-narrative tools specific to comics. For example, “crossover” refers to an object (a character, background, or speech balloon) that crosses over from one panel to the next. Identifying those peculiarities hasn’t really changed my process, but it’s pushed me to be more observant of my own and others’ work.

What is the basic unit of comics for you? Based on how intricate your pages tend to be, and how interconnected the panels are, I assume it is the page. But it could be the panel or the tier, or something else entirely, as well. Which one is it and why?

The panel (loose definition) is the basic unit, for sure. This is objectively and theoretically correct. But I can see why someone might think the page is my basic unit. I originally came to comics as an illustrator, so I experienced that classic problem of treating each panel like a standalone illustration, which is unsustainable and unnecessary. Eventually, I overcame that problem by treating the page as the illustration, with the panels and tiers acting as compositional tools alongside rule of thirds or framing.

The second volume of The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya functions as an invective against the Orientalism of the time, but also that of now. You incorporate European (rococo) ornamentation onto your pages to demonstrate that the Orientalism depicted originates not from Eastern cultures but from Western ones. You utilize vampirism as a metaphor for cultural appropriation. You yourself are neither Muslim or Turkish, and yet, you do not replicate the Orientalism so commonly found in Western comics. How, and why, did you manage this?

It helps that I am also the victim, subject, and stagehand of Orientalism. My lived experience consists of Westerners objectifying, romanticizing, or denigrating my race, culture, accent, and country based on their desires. As I became more conscious of the discourse of representation and the power dynamics of the Global North, I became aware of my and everybody’s role in the theater of the white, Western gaze. M. L., you and I probably understand what it’s like to perform our nonwhiteness for the benefit of safety, survival, strategy, or avoiding inconvenience: code-switching, hiding parts of ourselves, exaggerating others. Some of us consciously maintain the fantasy of a second authenticity — the kind that gets hawked in beach resorts, shops, homestays, and sometimes local films — because we need money and foreign interest to keep cultural traditions alive. That was what I meant by stagehand. TCMK allowed me to explore most of this, and root it in an uncompromising lens of the “Oriental” (myself, and main character Zeynel) turning the tables. TCMK was a subversion of different, sometimes contradictory, things: the vampire as Other, the vampire as white alluring dreamboat, the idea that in order to tell an anti-Orientalist story, it must perpetuate Orientalist imagery.

Yes, the carpet merchant selling his wares to a Western audience with its own gaze — own bastardizations of his craft and self — is, unfortunately, rather familiar. In the years since you began the TCMK webcomic, you’ve been nominated for an Eisner and put out books like My Aunt Is a Monster and Séance Tea Party (which is being adapted into an animated film by OddBot). How has your experience as a non-Western artist working in a largely Western-oriented global industry been?

I’m very lucky that my experience has been pleasant. It helps that I’m privileged enough to be fluent in English and be a longtime resident of digital art communities, so I am able to find resources easily. The work I published so far hasn’t yet explored my personal identities closely, so I have avoided that expectation to package my personhood as a consumable brand-name good. I feel any friction I’ll experience in the future will arise when I finally make that personal work, when Westerners will push back at Malaysian English.

You are a cofounder of UNNAMED, the Southeast Asian comics collective. There’s a clear pedagogic angle to much of your work, like with the extensive backmatter that teaches readers the steps you took to produce Séance Tea Party. TCMK is pedagogic in nature, too, as, for instance, you teach the reader how to weave with a drop spindle. What is the relationship between your art and pedagogy?

As mentioned earlier, I once had academic aspirations, and my singular life purpose is to share all of the wonders of the world. I’m transparent regarding my creative process because as a young artist, I wasn’t able to locate this sort of information (especially outside of American or Japanese contexts), and there were no mentors in Malaysian comics who left behind knowledge. If I ever show something inside a comic, it’s more to give context. As for the relationship between my art and pedagogy, it’s because I am not a very good speaker, nor am I compatible with the dryness and systemic financial bloodbath of academia. So all I have are the skills I actually got: writing and drawing.

You are also an admin coordinator at Hiveworks Comics, a creator-owned webcomics publisher currently putting out your take on the Alexander Romance. As Webtoon and Substack push to bring webcomics to the mainstream, why is it so crucial to you to have your own platform?

The internet is becoming more commodified and controlled by corporate forces — censorship of content imposed to please advertisers and payment processors; algorithms that push readers and creators to satisfy some random board member’s KPI (Key Performance Indicator); the visibility of numbers that brain-poisons people into minimizing their personalities in service of popularity. I think it’s healthy to be in control of your own space online, even if it doesn’t get as many eyes. You’re in control of how you want to present the space around your comic (more than just a plain white background!). You’re free to make mistakes and learn and draw at your own pace. You can make all that your heart desires.

I don’t think webcomic creators who want independence should only look at Hiveworks; you can make a space yourself through Tumblr, Wordpress, or Squarespace. This was what webcomics were for 20 years.

TCMK and Alexander are works that wouldn’t have fit on Webtoons or Substack. Those platforms cannot accommodate the double-page style and the pedagogical approach, by virtue of the user interface design — limited file sizes, poor archival or tagging systems, poor media editors, censorship concerns, and audience fit. Placing my webcomics on their own sites allows me to craft the site as part of the reading experience. For example, I wouldn’t have been able to include the transcript of Alexander on Webtoons or Substack, as there are no dropdowns built in to separate the transcript easily from the comics page and the author’s comment.

Seeing comics face yet another round of standardization, this time digital, has been rather disheartening. What webcomics are you reading that make good use of the form’s capabilities?

Admittedly, I haven’t been keeping up with webcomics due to my schedule, so I am not up to date on ambitious, form-expanding work. I enjoyed last year’s ShortBox Comic Fair, which featured 48 creators who made whatever comic they wanted. I am looking forward to seeing the collection for this year’s fair. I’m one of the artists for this year.

¤

¤

All images are taken from The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya books.

LARB Contributor

M. L. Kejera is a Gambian writer based in Illinois who was raised in Senegal, Saudi Arabia, and Tunis. He was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2020. A story of his was nominated for the Caine Prize for African Writing. His work has previously appeared in Lolwe, adda, The Nation, AV Club, and The New Inquiry.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Julie Doucet: How a Zine Author Went Canonical

Aubrey Gabel reflects on comics artist Julie Doucet's career and legacy.

The Art of Translating Comics: A Conversation with Hannah Chute

The translator of several French graphic novels discusses the challenges involved in translating comics.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!