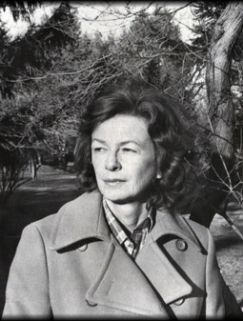

Tiger Lady: On Joan Williams

Faulkner tried the personae of mentor, father figure, and literary conduit in an effort to have a love affair that trumped the other roles.

By Lisa C. HickmanDecember 11, 2011

JOAN WILLIAMS SAID IT BEST herself when confronted with William Faulkner's curious and cutting response to a book-jacket-blurb request from her editor. "It was obviously," she said, "a very petulant kind of thing. Why couldn't he have just given me a nice quotation?"

Yet she knew why. For five years, 1949 to 1953, Williams and Faulkner experienced an ongoing tug of war over the personal and professional. Faulkner tried the personae of mentor, father figure, and literary conduit in an effort to have a love affair that trumped the other roles. Williams at 20 was no match for Faulkner at 50. She knew she had much to gain in the literary world from his affection and attention — and much to learn from him about the craft — but her reluctance to have sex with Faulkner made a sustainable love affair impossible.

Williams was never sexually attracted to Faulkner, and wanted a family and a husband close in age. His marriage and their age difference stifled her desire. About Faulkner's sexual prowess she said, "Well, he wasn't eighteen." She wanted to feel passionate — and she knew it was the promise of intimacy that helped keep the relationship alive — but she was unmoved by him. Faulkner was angry at her lack of response. He accused her of giving him "crumbs and subterfuge."

"I love you. Dont lie to me. I dont know which breaks my heart the most; for you to believe that you need to lie to me, or to think that you can." Vehement letters like this she labeled "pressure," and she responded to them by detaching and fleeing. Faulkner's overarching goal — to capture Williams's desire and win her heart — collapsed in 1954 when she married a young Sports Illustrated writer, Ezra Bowen. Faulkner wrote in November 1953:

I wont stop in. If this is the end, and I suppose, assume it is, I think the two people drawn together as we were and held together for four years by whatever it was we had, knew — love, sympathy, understanding, trust, belief — deserve a better period than a cup of coffee — not to end like two high school sweethearts breaking up over a coca cola in the corner drugstore.

¤

Williams was one of those rare people who could cut through the clutter to the heart of the matter in a few words. She was eminently quotable, and she often absorbed a difficult, shocking, or upsetting situation and summarized it with three words — "People are horrible." It was almost always appropriate and somehow made whatever had happened a little more bearable.

I met Williams in 1993 while working on a magazine article about Faulkner. And, over the years, I spent a lot of time with her and wrote a lot about her. (She could be quite a taskmaster.) She wanted me to write her biography, but I settled first on a book about her relationship with Faulkner (eventually published as William Faulkner and Joan Williams: The Romance of Two Writers in 2006). Though she always said that she already had written such a book with The Wintering, I knew when she handed me copies of the hundreds of letters from Faulkner and her letters to him that there was a much deeper, more complex narrative than her novel broached. Faulkner had the power to hurt her as she hurt him.

Williams was generous with Faulkner's letters. (She sold the originals to the University of Virginia, and copyright for the remaining unpublished letters rests with the Faulkner estate.) She shared many of them with Faulkner's first biographer, Joseph Blotner. She explained this generosity with such priceless material as a direct result of having Catherine Drinker Bowen for a mother-in-law; Bowen, a renowned biographer of Sir Edward Coke and others, often railed against sources who would not help her piece together the story of a life. Williams took that to heart, and helped others when possible.

She also remembered her mother-in-law as being fond of a saying originally from the French — "Abandon art for one day, and she will abandon you for three" — and Catherine Bowen lived by that directive. Williams wanted more of a family life and said, "I was not born to be the tiger Mrs. Bowen was. I never had such competitive spirit." (Ezra Bowen said his mother was "a writing machine who happened to also be a person, not a person who happened to write." His memory of Christmas was that she started work an hour later.) Robert Creamer, a fellow editor at Sports Illustrated, described Ezra as very athletic and patrician looking. "He was a good editor," Creamer said, "and as a writer he had a deft, sure touch." Sports Illustrated was a new magazine when Ezra was hired, making him a member of the original editorial staff. He later wrote for Time.

The happiest years of her life, Williams frequently said, were when she was rearing her two sons. An only child, she was haunted by loneliness her entire life — or perhaps she was just more open about admitting it than is usual — and she found writing a means of fighting that spectre.

¤

When Glen David Gold happened upon one of the book-jacket-blurb letters Faulkner sent Williams in a collector's catalog, he was intrigued by the transactional nature of the letter. In his Los Angeles Review of Books essay "On Not Rolling the Log (Transactions Along the Mississippi Delta)," Gold attempts to understand the hostility behind Faulkner's proffered book-jacket blurb, which read as follows:

"This is a compassionate and hopeful first novel, hopeful in the sense that I dont believe Miss Williams will be satisfied until she has done a better one."

— William Faulkner

The letter rankled Williams for years to come. When her editor, Hiram Haydn, approached Faulkner for a book-jacket blurb, Haydn was well known to Faulkner. They met in 1955 when Haydn succeeded Saxe Commins as editor in chief at Random House. By the time Williams's agent sent her manuscript to Haydn he had launched Atheneum Publishers.

Williams titled her 1961 novel after her earlier short story "The Morning and the Evening." The novel expanded on the feeble-minded central character of that story, Jake, who is dubbed "deaf and dumb" by his small, Southern community. The impetus for the story was a man she remembered from her childhood visits to Arkabutla, Mississippi who was taunted by some and asked if he was crazy. "Naw," he would respond, "but me ain't far from it." When Faulkner read her short story in progress, he wrote that "Jake is too good ... even for me to touch." A young editor at the Atlantic Monthly, Seymour Lawrence, accepted "The Morning and the Evening" in 1952.

Faulkner's familiarity with the novel's quality and subject did little to lessen his professed indignation at Haydn — "The more I think of whoever it was cajoling, frightening, pressuring — whatever it was — you into swotting up plugs to sell one of his books, the madder I get." His indignation was a thinly disguised attempt to excuse the stinging blurb he offered her.

Faulkner blamed Williams's marriage on her middle-class background. His haranguing, evident in some of his earliest letters, quickly became thematic. He wrote her often that she wasn't "demon-driven enough" for art and that her sexual inhibitions would keep her from developing her true talents. He chided her for running from herself and running from him. She must stop being afraid, stop running and accept the heat, fire, and sweat of the real world, the world of the artist. The anger in these letters Williams attributed to her "refusals of him."

Seven years had passed since her marriage to Bowen, yet the emotion in the letter Gold discusses was fresh. Faulkner harkened back to his persistent and painful topics. The blurb request also might have opened for Faulkner a long-standing transactional wound of his own. Perhaps he recalled his feelings when he approached Sherwood Anderson, a mentor and father figure, for help with his first novel, Soldiers' Pay (1926). Anderson, who had been so supportive, was immersed in a novel of his own when Faulkner needed help persuading publishers Boni and Liveright to take the novel. Anderson eventually wrote the publishers, saying, "I'll do anything for him so long as I don't have to read his damn manuscript."

Gold notes that Williams did achieve considerable recognition for her five novels and short-story collection — Mademoiselle College Fiction Prize 1949, Best American Short Stories 1949 honorable mention, National Book Award finalist 1961, John P. Marquand First Novel Award 1961, grant recipient from the National Institute of Arts and Letters 1962, and a Guggenheim Fellowship 1988 — but that provides only a glimpse of the rich literary life she inhabited.

Born September 26, 1928, in Memphis, Tennessee, Williams's sense of fictional place centered on Tate County, Mississippi, where her maternal grandmother, Arvenia Moore of Arkabutla, and other relatives lived. Every summer Williams traveled to rural Mississippi and rented a small cabin to gather material and write. During those absences, Bowen rented their Connecticut home and lived with Williams's aunt in New York City. After one of her summer sojourns, Ezra told his mother-in-law, "She's got to stop going to Mississippi every summer." "I guess he got tired of my going away for so long," Williams said. "But all my work came out of those summers."

Her parents were not particularly interested in literature, though her mother, Maud Moore Williams (1903-1997), read a good deal, and her father, Priestly Howard Williams (1895-1955), a salesman, made up stories in his head as he drove. Later, Williams said that that disclosure was as close as he ever came to telling her he wanted to be a writer.

Her father's life was the basis for her second novel, Old Powder Man (1966), in which P. H.'s bigger-than-life character emerged. A vigorous and talented dynamite salesman, he developed a way to use dynamite in the formation of levees, which helped increase his sales.Old Powder Man is one of the few novels (the only one I know, in fact) to meticulously re-create the days of levee camps. Reviewed by Doris Betts, Joyce Carol Oates, Louis B. Rubin, and Robert Penn Warren, among others, Old Powder Man was a critical success, something of a rarity for a second novel. Rubin wrote in the May 22, 1966, Saturday Review: "It is one thing to write a good first novel; to produce a second which is better is, I think, far more difficult."

She attended Miss Hutchison School for Girls in Memphis and received her B.A. from Bard College. During the summer of 1949, before entering her senior year at Bard, and fresh from winning the Mademoiselle College Fiction Prize for her short story "Rain Later," Williams met Faulkner in Oxford, Mississippi. For good or ill she was the only writer ever mentored by Faulkner, and the craft of writing dominates a significant number of their letters. During the five years of their relationship she published just the one story in The Atlantic.

Four books followed Old Powder Man: The Wintering (1971), a fictionalization of her friendship with Faulkner; County Woman (1982); a short-story collection, Pariah and Other Stories (1983), dedicated in memory of Faulkner; and a final novel, Pay the Piper (1988). Two of her five novels were reissued in the Louisiana State University Press series Voices of the South in 1994. Between 1981 and 1995 she published four short stories and an essay that remain — despite my best efforts — uncollected.

When Williams's path again crossed Seymour Lawrence's in 1984 — she had by then twice married and divorced — his situation had changed substantially. The young Atlantic editor who took her first major story was now a leading publisher of literary authors with his own Houghton Mifflin imprint. Williams lived ten years with Lawrence — he died in 1994 — sometimes helping him discover new talent. Observing Lawrence go about the business of book publishing continued and diversified her literary education. He did nonstop business on the phone and otherwise. He ended a cruise they were on prematurely, arranging for a helicopter to pick them up on deck. "Sam," she often said, "was always working." Williams lived ten years after Lawrence's passing. She died on Easter Sunday, April 11, 2004. (Faulkner fans will remember Easter Sunday as the last day of The Sound and the Fury. He gave Williams the handwritten manuscript of what many consider his masterpiece in 1952.)

Few writers' lives are intertwined with commanding figures like Faulkner, the tiger Catherine Bowen, and Lawrence. For Williams life must have been a frequent balancing act of transactional issues. Gold's essay illustrates there is much to this business of getting published, and not all of it, too little of it perhaps, rests with the quality of the work. Somehow Joan Williams fought through the maze of powerful personalities around her — she was more tiger-like than she imagined — as well as her own insecurities and weaknesses, to produce the novels and stories that eloquently render her aching themes of loneliness and separation, achieving finally a literary dwelling that is no one else's, that is her own.

LARB Contributor

Lisa C. Hickman is the author of William Faulkner and Joan Williams: The Romance of Two Writers; Stranger to the Truth, a narrative nonfiction work chronicling a high-profile Memphis matricide case; and editor of Remembering: Joan Williams’ Uncollected Pieces. She holds her PhD from the University of Mississippi and is currently at work on Between Grief and Nothing: Faulkner’s Later Years, from which this essay is excerpted.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Culture War

The only way to get to real cultural diversity is to tell stories in which the diversity is real.

Transactions Along the Mississippi Delta

On literary sociality and the romance between William Faulkner and Joan Williams.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!