Thorns, or The Things That Humans Do in the Name of Care That Are Something Other Than Care

In a preview of LARB Quarterly no. 38: Earth, Juliana Spahr explores the end.

By Juliana SpahrJuly 28, 2023

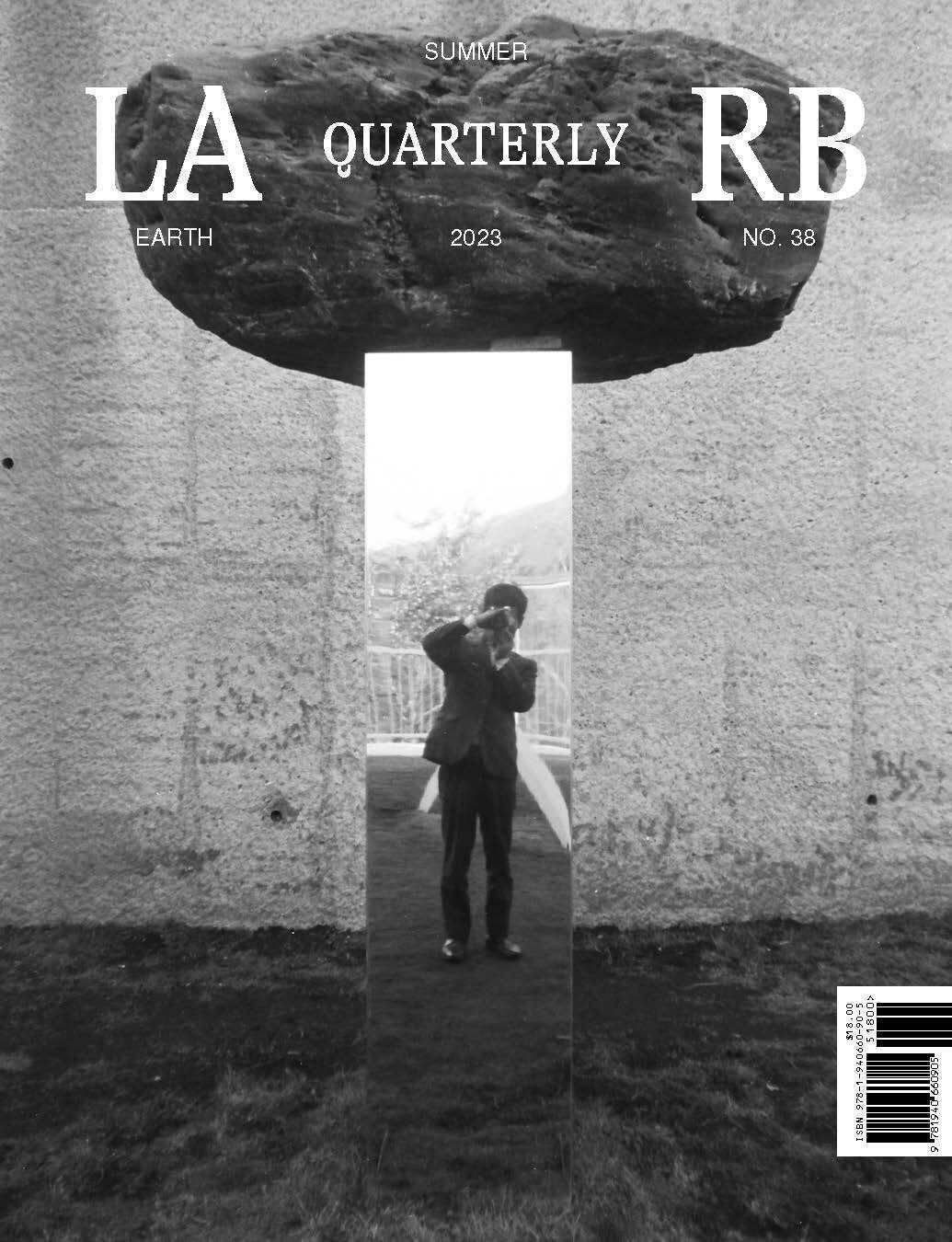

This article is an excerpt from the LARB Quarterly, no. 38: Earth. Subscribe now or preorder a copy from the LARB shop.

¤

A FRIEND TOLD ME a story about her elderly mom whose partner had died. It was a complicated story. The mom’s boyfriend had died in the hospital, during the one moment the mom had gone home for a break. When she came back, he had died so recently that the nurse had not yet closed his eyes, and his eyes, the panic in them, now haunted her mom. The mom dealt with the haunting by going to the bar every night. This was something new for the mom, a new way of being in the world that confused my friend. But also, the friend’s sister who lived with the mom was a part of this story and the sister’s many unemployed friends and there was a lot of coming and going. But as my friend told this story, a story with lots of chaos and anxiety, she kept returning to how there was cat shit all over the kitchen because no one would clean the cat box. When my friend was done with her story, I told her she had to read this new Hiromi Itō book, The Thorn Puller.

I did not tell her why, but I suggested this book because much of it is about taking care of one’s elderly parents from far away and flying back and forth and there is also a dog with a starring role. Itō (the book is written in first person but the chapter heads refer to this person as Itō) in the story gets her elderly parents a dog, but they are too old to care for it and the dog pees on the floor so many times the flooring has to be changed and then soon there are dried up pieces of dog shit in the corner, a sign of her mom’s decline. But what I did tell her was about how my mom was also not doing well, although in different ways. She had recently had another stroke and broken her hip and leg. The doctors had put in a rod and some nails to hold the bones together. The surgery was intense, and the recovery was difficult and would have been for anyone, but because my mom has dementia, she was constantly confused about why she could not walk. I had gone back to Ohio the first time to be there after the surgery and I was there when they moved her from the hospital and into rehab. And then I had returned a few weeks later to get her out of rehab and into assisted living as she was unable to return to her apartment. In between packing up boxes, moving boxes, throwing her stuff out, buying a recliner, and scooping her cat’s shit at her old apartment, I would regularly leave and go to her new room in assisted living and help her get to the bathroom. My mom at the time was more or less incontinent, mainly because she could not remember to press the button she wore around her neck that would bring someone to help her get to the bathroom. The button had arrived after the latest stroke and she could not get the presence of the button into her memory. I was worried about my mom sliding into permanent incontinence, so for the week I was there I would leave her old apartment to go to her new room every two or so hours. When I got there, I would first help her up and into the wheelchair and then once in the bathroom, after I got her standing, I would pull her pants down, then her diaper down, and help her shuffle around so she could sit and then I would stand there while she went to the bathroom. When there she often pooped, a soft, slippery sort of poop with a strong smell. And when I handed her the toilet paper, she would wipe so vigorously that I kept having to say, “Mom, don’t wipe back and forth because of infections.” This is how The Thorn Puller begins, with Itō, her mother having just had a stroke, taking the mom to the bathroom, dealing with her “soft, slippery bowel movement,” getting it on her hands, and the stink never going away. Not in a bad way. “Yeah, we eat, we shit. And our shit stinks. Honestly, those are the most natural things in the world,” she thinks. But she is clear that she is dealing with shit: “Mom’s loose stools were shit. They had the same foul smell as the ones I make.” And yet as normal as it is, these sorts of moments are not part of the range of content that is often included in literary narratives and Itō’s genius as a writer is in recognizing these moments and spending some uncomfortable time there with them, all the while insisting it is normal.

My friend had been flying back and forth to Las Vegas all year, dealing with the heavily drinking mom and the sister and the sister’s friends and the cat’s shit. She would often text me when she was there. The trip with all the bathroom visits was the second trip I had made back to Ohio in less than a month and I had texted her too. We would text about the weirdness of where we had arrived. A great deal of The Thorn Puller is about flying back and forth between Japan and California, dealing with two elderly parents in Japan, a much older and elderly husband in California, and a teenage daughter who traveled with her. My partner, while not much older than me as both of us are heading into elderly, was flying a lot to care for his two elderly partners who were in Florida. His mom had a stroke a few weeks after my mom. His dad was losing circulation in his feet and was at risk of amputation. A few weeks later, the mom was out of the hospital but the dad was in the hospital, fitted with a defibrillator vest. My partner would also text me stories about the weirdness of where he had arrived. In one story his mother on the way home from the hospital after her stroke insisted on getting a martini at a nearby bar because, she announced, it had been a hard week. I was also texting with another friend who was dealing with her mother who had a wound that would not heal and was constantly oozing after a minor surgery, and no one could get it to stop. She was dealing with a divorce and a teenager too and at one point she had her father-in-law living with her and then her mother-in-law moved in too after she left the hospital and then her son returned to live with her. She lived, like everyone else in this story, in a small, modest house, so the mother-in-law stayed on the couch in the corner of the living room as she recovered. I texted her too that she should read The Thorn Puller.

And yet another friend. I also told her to read The Thorn Puller when she was trying to help her mother-in-law who had never worked in her life, and thus had no income, find a senior living apartment cheap enough that my friend, of fairly modest income, could pay for it. This search went on for many months and involved much filing of waivers, but whenever one of the places wrote to the mother-in-law to notify her of an opening, the mother-in-law threw the letter out, saying she did not need to move. But she did need to move, for many reasons. The main reason being that the landlord had said she had to move. So, the search continued. And while the search happened, life went on. The brother-in-law died after many years of drug use. Numerous people in the family got COVID-19. My friend’s partner switched jobs two times, stressfully and not for the usual reason of increased income or sense of purpose. And my friend, like myself and like the friend with the mother with the wound that would not heal, first lost her job and then unlost her job. We all taught at the same small liberal arts college, and it had briefly been shut down because it could not make payroll and then a few weeks later a big polytechnic university acquired the college and we all unlost our jobs. The unlost jobs, as relieved as we were to have paychecks, were also part of the problem. The jobs we unlost were in no way the same as the ones we had lost. The jobs had become difficult and complicated, depressing too, as most of the people we respected had left in the first few years, and the new culture of the polytechnic university was very different than that of the small liberal arts college. The university tended to treat us less as faculty and more as ghosts and when they did notice us it was usually to tell us that they were not going to listen to us, although they did pay us regularly and that was a relief because we all needed money for elder care.

At some point, I texted my friend with the mother-in-law who needed housing about this moment where we were trying first to keep our jobs and then, once kept, trying to do our jobs, about family, about my teenage son who both needed and did not need me in the time-honored tradition of teenageness, about my partner who went around the house saying “I hate you; I hate you” to himself and it seemed to be about his job teaching math at an urban high school, about the cat box full of shit too, and about how I was going to have to move my mom from Ohio to live in the corner of our living room, the only room available in my modest house, because I could not afford to leave her in assisted living. The inability to leave her in assisted living was partially my fault. I had done funny things with her small amounts of savings that disqualified her from state assistance until I paid the money back, which I could not do because my salary was also modest because the small liberal arts college had frozen all salaries 10 years ago and the polytechnic university was refusing to pay us the going rate. In the middle of my self-involved inventorying of my woes, my friend texted me back, “Lol. I was reading the part in thorn puller last night before bed where she’s heaving her body from surface to surface while bleeding too much after some kind of uterine surgery bc her elderly husband is too weak to help her stand up which neither of them say but both of them know and she has to get to the car to go to ER and it was oddly deeply very comforting.” I knew immediately what paragraph she meant. It was this one: “Incessant waves of nausea and dizziness washed over me. I tried to stand but couldn’t, I tried to walk but couldn’t. I threw myself toward the wall in front of me, and when I crashed into it, I stopped. I leaned on the wall with all my weight, then threw myself forward again toward the table a few steps away, and when I crashed into that, I stopped again. Using this method, I inched closer, step by step, toward the car outside.” On its own, this paragraph might not seem like much, but in context, it does a very good job of describing those moments when you have no other option than to pull yourself forward, despite being barely able to do it, while another person that you rely on for help and support is unable to help you and instead stands there watching.

At the same time I was reading The Thorn Puller, I was trying to write something. For a number of months, I had been reading The New York Times on my device for about half an hour in bed after I woke up. My partner would leave to go teach and I didn’t have to start work until later because I taught at night, so I luxuriated in the mumble freedom, although reading The New York Times seemed like a misuse of this precious mumble free time. So, in a halfhearted attempt at self-improvement, and also in an attempt to fulfill the obligations of my job because the rare moments when the polytechnic university noticed us they usually were insulting our research output which they seemed to feel was not up to their standards, I decided I had to stop reading The New York Times on my device in bed. I made a rule that I was only allowed to stay in bed if I wrote something on that same device. I had decided I wanted to write something about crows. I am someone who loves crows, loves their loud squawks, the way they tilt their heads when looking at you. I love their eyes filled with what I imagine is a searching intelligence, an intelligence of connection. I also love their communal ways, the way they roost together, loudly exchanging information as they settle in for the night. I wanted to write though not just about any crow but about this specific crow called the ʻalalā. The ʻalalā had lived in Hawaiʻi but were now extinct in the wild. The ʻalalā is a beautiful and smart crow. Beautiful and smart basically describes all crows. But the beauty of the ʻalalā is that they have wings that are a little more rounded and a bill that is a little bit thicker. And as for smartness, they know how to use sticks as tools. The ʻalalā, to my disappointment, did not nest communally like the common crow. But still they shared. They often treated trees as pantries, caching ʻoha kepau and ʻōlapa fruit clusters in the crotch of branches or twigs of trees near the nest so as to feed their partners when they were busy with incubating or brooding.

The ʻalalā went extinct in the wild, but there were nine crows still alive in a lab. These nine were now being bred by a team of humans who wanted to reintroduce them to the wild. It sounded like it was not a great thing to be one of nine remaining ʻalalā. ʻAlalā are among those birds who are monogamous and form strong bonds but when held captive were forced to breed not for compatibility but for genetic diversity and so they were provided only with one mate at a time. Frequently the two ʻalalā did not want to mate. But for those that did, after they laid a clutch of eggs, someone from the team of humans would go in and pull the eggs away so the ʻalalā would think the first clutch had died and produce a double clutch. But even when the ʻalalā laid the double clutch, the eggs were still often taken away and the chicks were raised by humans. The humans did not trust the ʻalalā to raise their own eggs. They felt the ʻalalā were bad parents. In this way, at great expense and much trouble, the humans produced about 15 ʻalalā each year. There it got complicated again for the ways it is not great to be one of the remaining ʻalalā seem to be many. One year, at the beginning of the rewilding, enough birds had been produced that 30 were released. And very shortly 25 of those 30 were dead or disappeared. The humans then recaptured the five remaining birds. They decided that part of the problem was that the captive ʻalalā no longer recognized the ʻio as predatory and so were quickly eaten. The humans set about to train the ʻalalā to recognize the ʻio as a danger. This involved bringing in a glove-trained ʻio and a taxidermied ʻio. The humans would attach the taxidermied ʻio to a pulley and have it mimic flying over the ʻalalā’s cage and then another human would stand at the cage, body hidden, holding out an arm with the glove-trained, live ʻio so that the ʻalalā could see the ʻio. Then another human would play prerecorded ʻalalā alarm calls and as the calls continued, the human with the glove would put a dead ʻalalā underneath the ʻio’s feet, moving their arms up and down, the ʻio balanced on the glove, awkwardly. This was what I thought I wanted to write about.

I had convinced myself that I wanted to write a small book, one more idiosyncratic in form and content than encyclopedic. At first, I thought I wanted to write a book about emotions, about the emotions that I felt when I watched the videos of the captive ʻalalā. About the odd look in the glove-trained ʻio’s eyes as the dead crow was shoved underneath it to demonstrate the predator training protocol. About how in another video the woman who came to feed them would first put a black shroud over her head as if she were a druid, climb a ladder, and attach a food dispenser to a fence.

At the time I was partial to writing poems that had lists of animals in them. I had in the past used elegy to talk about endangered species, listed names of extinctions as if in real time, created fake ecosystems to suggest connections in the poems that I wrote. But now I wanted to deal not with the natural world but with humans trying to respond to ecological crisis of their own invention, not by stopping doing what they were doing that was causing birds like the ʻalalā to become extinct but instead by pulling a taxidermied ʻio over the cage of the ʻalalā, playing ʻalalā alarm calls, and holding a captured ʻio out near a cage with a dead ʻalalā shoved underneath it. It was the things that humans do in the name of care that are something other than care that I found so enticing in this ʻalalā story.

I imagined this small book having this as its opening sentence: “There once were only nine ʻalalā left and these nine were bred by humans to produce other ʻalalā that were then trained by those same humans to be introduced back into the wild where they were then eaten by the also endangered ʻio.” I was not sure this was the right sentence. But at the same time, I thought this sort of sentence would exemplify my concerns with avoiding the romanticization that defines the writing about what some people call “endlings,” or the last known example of a species. I did not at all want to write something about taking care of my mother. But it did not occur to me that maybe I was interested in the story of the ʻalalā because my mom was also a sort of endling, at least to me, and stuck in a version of a cage. But I did not let myself have this thought while flying back and forth to Ohio every few weeks and getting no writing done. The more likely explanation, despite my grand plan and my statements of intent, was that it was not really the ʻalalā that I needed or wanted to write about, it was rather the absurdity of the caretaking. My mom had a million times said to me that I should never drop her off at a nursing home or an assisted living facility. If she ever got dementia and was in diapers, I was to let her die.

Itō does a good job in The Thorn Puller of explaining the constant feeling that there is not room for one more thing and then yet one more thing comes along all the time because life is a list of things that happen and is never still. For me, I felt the absurdity peak when I began the process of trying to move my mom out to California so she could live in the corner of my living room and began to try to figure out the California medical care system, a system that was much better but therefore much more complicated than the one in Ohio. For weeks before she moved, I got up and did my calls, as I called it, for at least an hour each day. Among the people I called were a lawyer who for a fee would help me apply for Medi-Cal; someone who was basically a real estate agent for assisted living facilities who would be paid by the facilities if we found someplace although none of the places were affordable; a person who would help me find the right version of Medicare insurance for my mom in California who would be paid by the insurance company if I worked with her; some guy who kept calling me when I naïvely gave my phone number to some site so that I could see the rates for an assisted living facility and who seemed slightly bad at his job, which was also to be a sort real estate agent for the elderly; someone from a nonprofit whose website featured stirring patriotic music and lots of flags and who would for a fee help me apply for veteran’s benefits for my mom, a service I needed because the free versions of assistance with these forms that the veteran’s sites recommended never returned my calls or my emails and their website warned me not to come by their office; my own tax accountant who for years I had paid to do my taxes and who seemed annoyed by my questions; an elder lawyer in Ohio who had been helping me understand Ohio Medicaid who I also paid, and a social worker who I would pay if I wanted them to figure out where I might get medical help for my mom. There were, I learned, a whole range of other services that had unclear costs or unclear requirements, many of which my mom could never receive because she had a small pension from her years of being a schoolteacher, which meant that she made too much money to qualify for many things but not enough money to pay for the level of care she needed. Many of these people seemed as confused as I was and gave me contradictory advice and it was never clear to me what was true. In the meantime, I kept paying more than I made in a month each month I kept my mom in assisted living in Ohio.

It was not surprising that my friend referenced The Thorn Puller when I complained to her. We are, my friend and me, part of the Hiromi Itō fan club. Or so we decided years ago when we brought Hiromi Itō to read at the MFA program that was offered by that small liberal arts college. Hiromi Itō read that night from Killing Kanoko, her book about motherhood and depression written after her daughter was born. While The Thorn Puller says a bunch of things that I have never seen anyone say in literary fiction about elder care and late-in-life partnerships and the difficulties of raising teenagers and dealing with one’s own bodily decline at the same time, Killing Kanoko said the same about caring for an infant. The poem “Killing Kanoko” is willing to go to the dark place: “congratulations on your destruction” is one of its refrains. But also passages like this: “After six months / Kanoko’s teeth come in / She bites my nipples, wants to bite my nipples off / She is always looking for just the right moment to do so / Kanoko eats my time / Kanoko pilfers my nutrients / Kanoko threatens my appetite / Kanoko pulls out my hair / Kanoko forces me to deal with all her shit / I want to get rid of Kanoko / I want to get rid of filthy little Kanoko / I want to get rid of or kill Kanoko who bites off my nipples.” I had a young son at the time whose teeth had just come in and who was also biting my nipples regularly. When this happened, I would scream ouch loudly, then he too would begin to scream and there we were, my boob hanging out in public, him loudly causing a stir because I had loudly caused a stir. Every time, I felt as if I was being a bad mother by reacting to the pain and not being able to gracefully pull my child’s mouth off the nipple and then just as gracefully reattach it and do it with such ease that he did not scream. I was convinced that all the good mothers, those who really enjoyed their babymoon, knew how to do this. This, as you might imagine, made reading Killing Kanoko feel as if someone had finally walked across the room to me when my baby screamed after I went “ouch” and told me that I wasn’t a bad mom because I went “ouch.” Something that never once happened.

The night that my friend and I created and then joined the Hiromi Itō fan club, Kanoko, the daughter whom Hiromi Itō had, of course, not killed and whom as far as I could understand she loved dearly, was there. Kanoko played some instrument she had made, and the music was the sort of experimental music that was made at the small liberal arts college. It was exciting and lovely and I remember thinking that night that poetry could do some work, something that I do not feel that often. And I also remember standing outside the reading on the porch of the building because my friend at that time still smoked and we were talking about how there needed to be a Hiromi Itō fan club. This was a very different time, a time when the small liberal arts college was somewhat functioning, and the room was packed with people to see Hiromi Itō, and my friend still smoked which meant we were younger and less worried versions of ourselves, a time when we had time to joke about a fan club. Now literature feels sort of like an afterthought.

I have this theory about poetry in this moment. I do not tell many people who write poetry about this theory because it annoys them and then they complain about it all over the place and then I get annoyed and feel bad at the same time. My theory is that we are in a moment where all the poetry is a form of heroic confessionalism where people talk mainly about their lives, as many poets have over time, but unlike before so many of the poems right now feature the author as the hero of their stories, someone who triumphs or rights wrongs or scolds people who are wrong loudly and convincingly. Poetry has become self-hagiography. Sometimes when I read poetry, I think of it as telling the stories of these godlike figures who always know the right thing to do and then who get right on it and do it, helping everyone be better, fighting injustices in their various ways, some despite oppression and some righteous in their refusal to be the oppressor. This work can, like all poetry, be good or bad. But even when it is good and I admire its skillful turns and its beautiful metaphors and maybe I go ohh marveling at the narrator’s abilities to right wrongs or out of respect for their strong righteous anger, I find it little comfort.

Sometimes I just want someone to say something fucked up in their poem, to confess some fucked up things they thought or did, some moments when they realized not how they were triumphant but how they were on the wrong side or they did something disgusting or their body did something disgusting without their consent or someone did something disgusting to their body and they dealt with it or enjoyed it or maybe just did not mind it. Congratulations on your destruction, I want someone to say. And this is the reason why I am a member of the Hiromi Itō fan club, a club with no membership cards and no dues and only a few other members who never hold meetings.

In each chapter of The Thorn Puller, Itō references a bunch of other writers and she is, she says, imitating their styles. I can’t hear these voices because most of these referenced works are not translated and I’m stupid in my monolingualism. But it is a nice way for a writer to be in the world. It is nice to think about how the stories we tell are created over time and are impossible for any single individual to own, something I believe so strongly that I sometimes end up on the wrong side of all the debates about appropriation. Itō’s stories tend to end mid-narrative, as if they were fables. In the one about the bleeding, it ends with Itō unable to get herself into the hospital, so while her husband goes to get a wheelchair, she lays down in the parking lot and as the winds blow over her she realizes that there is a wildfire nearby. Eventually she is picked up and taken into the hospital and it is unclear what is done to make her better because suddenly there is a story about the dog and then another call from her dad about her mother and the hospital has just disappeared. This chapter ends the book, and it ends with a moment where Itō and her husband and her teenage daughters have driven to the snow to go sledding. Itō has hurt her neck and so does not want to turn and feel the pain but her daughters call to her and she turns despite the pain: “I felt myself shake again. I shook until I felt myself. I exist. Here. Meanwhile, they were shouting themselves hoarse. I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive! I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive, I’m alive!”

On one of these many trips I made to care for my mom, I can’t remember if it was the time she was recovering from bladder cancer or the time she had her gallbladder removed or the time she had her knee replaced, one by one my mom’s friends came by to check on her. I was at the dining room table working on her accounting as the friends came by. This was about five or so years ago and it was when the opioid crisis was at its peak and my mom lived in the center of the opioid crisis. As I worked, I listened to them tell my mom their stories, so many of them about their children and opiates. There was one about a son who had a drug problem and while his girlfriend, also with a drug problem, was in jail for theft, he took up with another much younger girl who also had a drug problem. Around the time the girlfriend got out of jail, the much younger girl overdosed. The son and the girlfriend did not tell anyone the girl had died, and they buried her in their backyard. Eventually, the girl’s body was dug up and that was what the story was about. It was about what her body looked like. It had become purplish black, the woman said, unrecognizable. And she said it several times. The story stopped there. There was no presumed ending. It was a story that could not accommodate an end and all it said was I’m alive.

¤

LARB Contributor

Juliana Spahr is the author of several books of poetry, prose, and scholarship, including — most recently — Du Bois’s Telegram: Literary Resistance and State Containment (2018) and That Winter the Wolf Came (2015). She was awarded the Hardison Poetry Prize in 2009 and is currently professor of English and dean of Graduate Studies at Mills College.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Withering Green Rush: California Cannabis Breeding at a Crossroads

In a preview of LARB Quarterly no. 38: Earth, Ali Bektaş examines one of the state’s most contentious and consequential industries.

Illicit, Offshore, Shadow, Invisible: Financial Thrillers and Global Capital

In a preview of LARB Quarterly, no. 38: Earth, Editor-in-Chief Michelle Chihara explores the opaque world of global finance.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!